With the fall of most communist countries at the end of the Cold War and in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square protests, scholars have given considerable attention to whether China will ever democratize. Many, such as Minxin Pei, remain optimistic about China’s likely democratization. Pei stipulates that some of the greatest opportunities to democratize will arise from China’s decreasing poverty rate and an increasingly literate population. The rise of a wealthier, more educated citizenry undermines Mao’s original cry for a revolutionary peasant class, perhaps instigating a subconscious shift away from communism and towards democracy. Pei similarly suggested that a “financial meltdown” similar to the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis may usher in democratization.

Others, such as Benjamin Herscovitch, argue that China’s “accountable authoritarianism” prevented the social pressures one would typically assume with economic development. The Xi Jinping administration, starting its third term in March, shows no evidence of political reforms but rather increased repression. The Xi Jinping Administration has also attempted to reframe global discourse about democracy by arguing that the results of government policies should grant a government more legitimacy. Furthermore, despite the Chinese government’s white paper, “China: Democracy That Works,” which claims that China’s one-party system exists as its own “evolved” form of democracy, it is clear that the regime has little interest in democratic reforms. Considering the increased concentration of power under Xi, the entrenchment of this system suggests little likelihood of democratic reforms in the near future.

While surveying Chinese citizens about this is impractical, we questioned whether Americans, especially in a time of heightened tensions with China, view democracy as possible in China. Such a question attempts in part to tap into beliefs on whether current conditions can change. An American public that sees no hope for democratization may be less willing to see Chinese political and economic concerns as valid or worse, transfer these feelings to beliefs about Chinese people and the suitability of democracy.

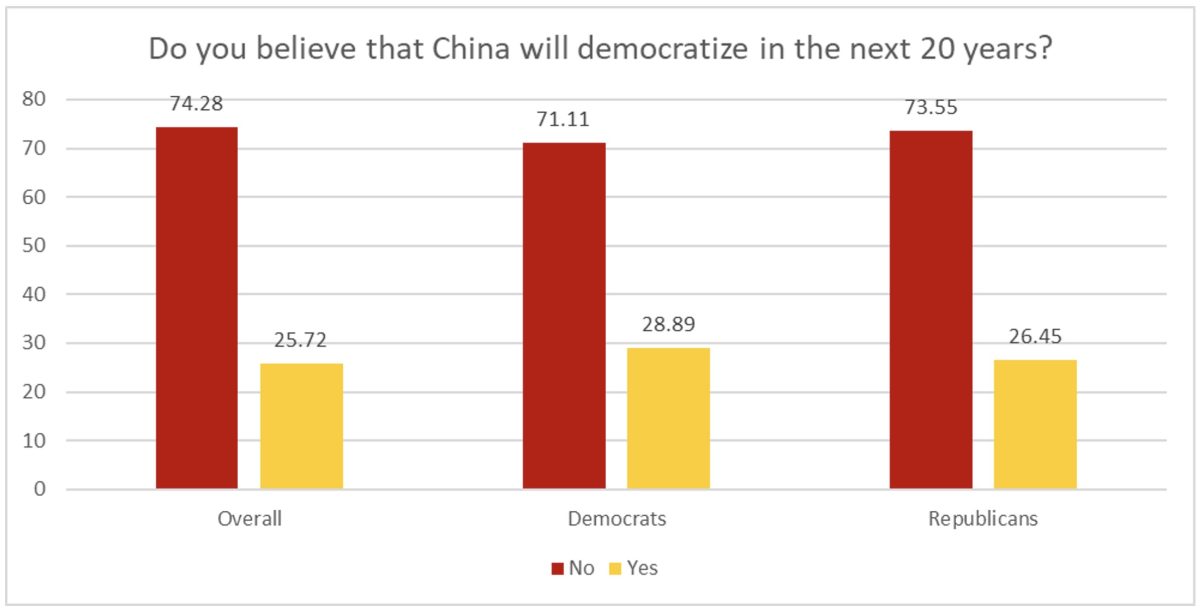

We asked 1,213 Americans, recruited via mTurk Amazon on February 28, 2023, a series of questions related to China, including “Do you believe that China will democratize in the next 20 years?”. See Figures 1 and 2 below.

We find that roughly one in four (25.72%) believe China will democratize, with only marginal differences between Democrats and Republicans. We also see a clear distinction by age, with older respondents less likely to believe China will change. For many, the crackdown at Tiananmen Square likely shaped beliefs. Our data shows that respondents under the age of 44, which would be those ages 10 or younger at the time of Tiananmen, were more likely to believe that China would democratize. 30.24% of respondents aged 44 or younger believed democratization could occur. That number dropped to 17.66% for those over 44. We do not see much difference in beliefs for older cohorts (e.g. 55 and older, 65 and older), again implicitly suggesting the lingering effects of Tiananmen on views.

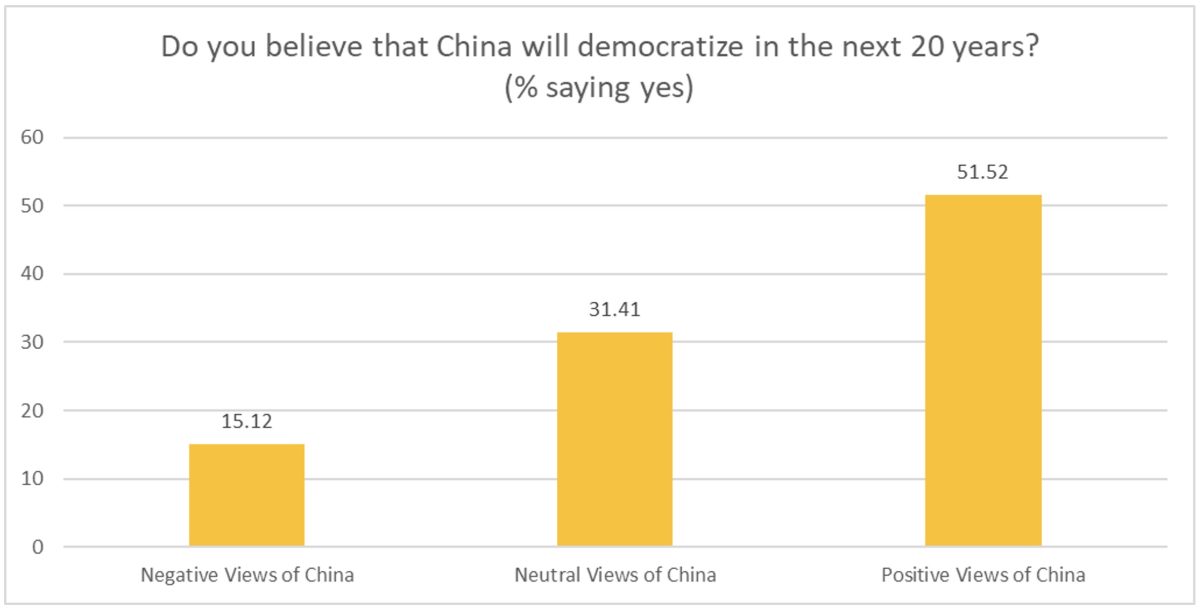

Even if Tiananmen was not necessarily the frame of reference for respondents, we still assumed that views on the likelihood of democratization were partially a function of previous beliefs about the country. Earlier in the survey, we asked respondents to evaluate China, as well as nine other countries, on a 1-5 scale, with 1 being very negative and 5 very positive. Unsurprisingly, very few of those with preexisting negative views of China (a 1 or 2 on the scale), 15.12%, thought China would democratize. A slight majority of respondents with positive views of China (a 4 or 5 on the scale), 51.52%, thought that China would democratize in the next 20 years.

Regression analysis provides additional insight. We find that respondents who self-identified as being more conservative were slightly more likely to believe China will democratize, while education also positively correlates with this belief. Respondents who expressed a greater interest in international affairs were also slightly more likely to believe that China would democratize. Age and household income however correspond with lower expectations that China will democratize.

Democratization is hard to predict, especially since citizens will rarely reveal their true preferences while the authoritarian regime maintains the ability to punish, and as such, authoritarian regimes that appear stable one day can quickly collapse under underlying pressure. The survey results suggest that Americans do not expect to see significant political change in the Chinese government in the near future, likely due to broader pessimism about China. While we found no recent survey work asking about Chinese democratization, the closest survey we could find was a Pew 2021 survey showing that Americans did not think Chinese leaders respected individual personal freedoms.

Other recent survey work shows that American public opinion is increasingly hostile toward China. Surveys from Pew Research show American opinions souring on China based on a myriad of factors, including the Covid-19 pandemic, trade policies, China’s human rights policies, and its cooperation with Russia during its invasion of Ukraine. Separate surveys from Gallup and the Chicago Council of Global Affairs, conducted in early 2021 and late 2020 respectively, show that Americans view China’s economic rise as a threat to American interests.

Admittedly, this survey cannot capture directly why Americans feel pessimistic about China’s potential to democratize since we only asked a binary choice question with no related follow-up questions. It is also possible respondents only considered China’s limited potential to transition to a fully functioning democracy rather than a hybrid or flawed democracy. However, a public that does not see political change as possible in China risks promoting policies that both reinforce hostilities and inhibit incremental change.

Figure 1

Figure 2

This survey work was funded by generous resources from the Mahurin Honors College at Western Kentucky University.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Global South in Times of Crisis: A China–Africa Relations View

- Contesting American Power: Beijing’s Challenge in South China Sea Disputes

- Opinion – The Status of China’s Confucius Institutes in American Universities

- Continuity and Change: China’s Assertiveness in the South China Sea

- Opinion – Are American Policies towards China a Path to Technological Bipolarity?

- Public Diplomacy: China’s Newest Charm Offensive