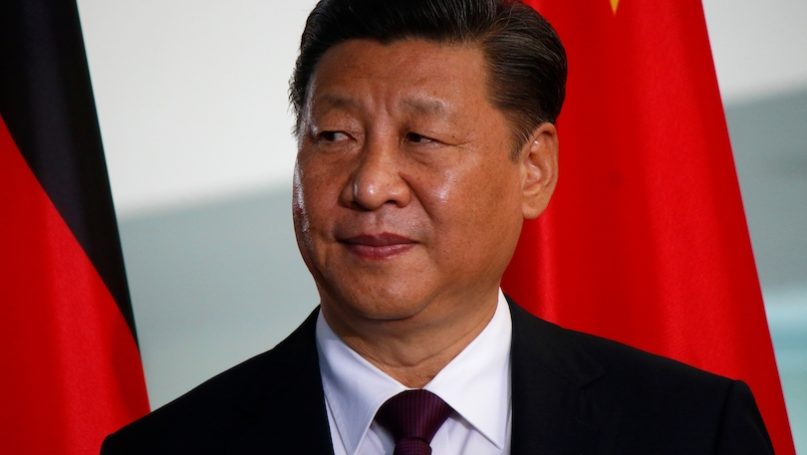

The Global Security Initiative (GSI) was brought to the public attention by President Xi Jinping during the Boao Forum in April 2022. When it was publicized for the first time, the GSI was far from clear and detailed, but on 21 February 2023, the State Council promulgated the GSI’s Concept Paper that explains the Initiative further. The Paper unravels the mystery behind China’s global power intention (or ambition) and adds to the public interest on the GSI and the implication it may have on the current global order.

As China’s power grows, it aspires to contribute more significantly to the world. Moreover it has an ambition to direct the course of history, instead of becoming a spectator. So far, China has played a key role in the global economy, particularly world trade, technology innovation and development assistance to underprivileged countries. Through the Belt and Road Initiative, China has assisted infrastructure building in 151 states. China thinks it is time to expand its clout beyond economics, especially in the fields that it often suffers deficit – such as political trust.

Bluntly speaking, the GSI is China’s regional and global architecture. It is Beijing’s effort to shape a new world order with Chinese characteristics. On the one hand, China has been successful under the US-dominated ‘Pax Americana’ system that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. On the other hand, after growing in power in recent decades, China thinks the current order can no longer accommodate its growing interests. Hence, China’s need to revise or modify the current world order to accommodate its “dream”.

There are some principles that support the current order in the GSI. Firstly, the GSI upholds the global system based on the UN role, the UN Charter and international law. The GSI perceives UN authority as a means to global governance and peace keeping. Regardless of China’s reservation to the UN on several areas such as the Xinjiang issue, the Concept Paper acknowledges UN as the platform to maintain global peace and growth.

Secondly, the Paper also supports ASEAN centrality as a regional platform to maintain peace and stability in the Southeast Asian region. It advocates the ASEAN Way of consultation and reaching consensus (musyawarah) in accommodating different views. This principle is in ASEAN’s interest to reject major powers’ unilateral acts in the region.

Thirdly, the Paper demonstrates its concern on developing countries and unstable regions. For example, China’s peacekeeping forces have been a significant presence in conflict areas in Africa under the banner of the UN. Similarly, China promotes financial sustainability for the African Union in executing its peacekeeping mission. Likewise, China supports the empowerment of regional mechanisms in Latin America, Caribbean and the Middle East and urges regional independence in maintaining security.

Nevertheless, there are some revisionist aspects of the GSI that needs to be highlighted. Firstly, the Concept Paper develops an understanding of international law that serves Beijing interests. It emphasizes the main principle of international law that is sovereignty, equality among sovereign states and non-interference. On the other hand, it avoids mentioning dispute mechanism as one of the international law principles. In other words, it highlights parts of international law that suit Beijing and denies parts against its interest.

Moreover, the Paper overemphasizes political mechanisms in resolving discord. In the 5591 word-long (Mandarin version) or 3505 word-long (English version) documents, political solutions are mentioned five times. The Paper rejects dispute mechanisms, such as arbitration and tribunal, in resolving inter-state disputes – including in the maritime realm. The Paper perceives a political mechanism as the only effective means to dispute resolution, demonstrating China’s intention to modify the current order. Particularly, China has its own view on international law, which is concerning. The rejection of the international law mechanism as peaceful means to resolve inter-states disputes is China’s effort to reshape international order to accommodate its national interests. The overemphasis on political mechanisms in dispute resolution has been the Chinese way in dealing with disputes – though this is not distinctly Chinese since other major powers also prefer political means. Yet, if major powers have no respect for dispute mechanisms, equality among sovereign states is an empty slogan.

In addition, the GSI Concept Paper also seeks to foster the regional platforms or organizations which have China as the initiator or core member, such as Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), China-Africa Peace and Security Forum, Beijing Xiangshan Forum, Global Public Security Cooperation Forum (Lianyungang Forum) and BRICS. This point gives an impression that China aims to play a more decisive role in global politics and security by replacing the role of the US and its allies.

For the South China Sea littoral states, China’s rejection of the dispute mechanism means Beijing reiterates its opposition to the 2016 Tribunal Ruling that invalidates its nine-dash claim in the South China Sea. This attitude is not constructive to regional peace and stability. If China wants to build its moral legitimacy as a global leader it must not abandon the dispute mechanism as one of the core principles of international law.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Global South in Times of Crisis: A China–Africa Relations View

- Opinion – The Impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative on Central Asia and the South Caucasus

- Opinion – China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Pragmatism over Morals?

- The Implications of China’s Growing Military Strength on the Global Maritime Security Order

- China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Debt Trap or Soft Power Catalyst?

- Challenge or Opportunity? EU-China Economic Cooperation and the Belt and Road Initiative