This article is part of the Buddhism and International Relations article series, edited by Raghav Dua.

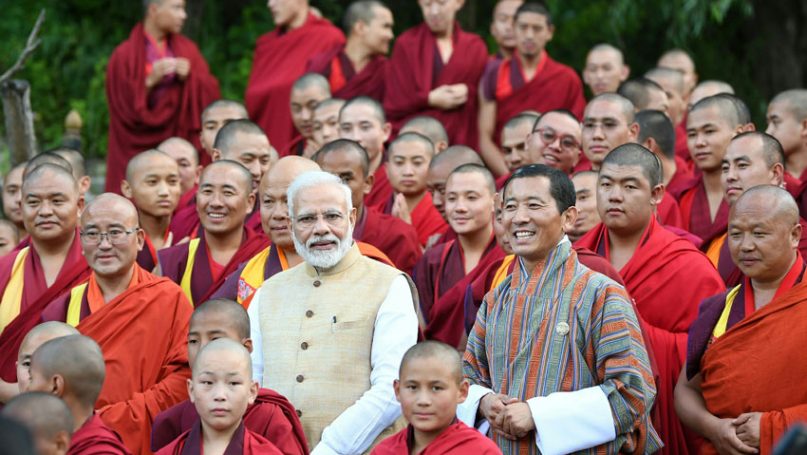

Strategic utilization of Buddhism in Indian foreign policy is a feature that has become particularly noticeable in the last decade, under Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) which took power in 2014. Modi has pushed an “Indian vision of Buddhism” which “appeals to ancient history while rooted in contemporary geopolitical concerns” (Lam 2022). The geopolitical concerns reflect the deterioration in India’s relations with China on show with confrontation, casualties and conflict along India’s Buddhist Himalayan frontier – at Doklam in 2017, Galwan in 2020, and Yangtse in December 2022.

Leading analysts were already noting by the end of 2014 that “the PM has put Buddhism at the heart of India’s vigorous new diplomacy.” Two examples suffice from September 2015. At the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, Modi proclaimed:

We in India would like to develop Bodh Gaya so that it can become the spiritual capital and civilisational bond between India and the Buddhist world. The government of India would like to provide all possible support that its Buddhist cousin nations need for the satisfaction of their spiritual needs from this holiest of holy places for them.

That same month, Modi also initiated a “…‘Samvad’ – Global Hindu-Buddhist Initiative”, in which “India is taking the lead in boosting the Buddhist heritage across Asia.” This Samvad initiative was enthusiastically embraced by Japan’s leader Shinzo Abe. A Samvad framework was then pushed jointly by India and Japan in subsequent years, a geocultural use of Buddhism to offset the geoeconomic allure of China’s Silk Road project.

India is a rising power, with rising hopes for influence in and around its immediate and extended neighborhood. Its power projection is multi-faceted, with geocultural linkages sought for geopolitical purposes. Kishwar noted the “rising role of Buddhism in India’s soft power strategy” in 2018. This soft power Buddhism-facilitated diplomacy is also evident with regard to India’s strategic partnerships with Japan and Mongolia (Sarmah 2022), as well as with Vietnam and South Korea, and with regard to Indian outreach to Thailand, Myanmar and Sri Lanka. Tibetan Buddhism has been “a source and strength of Indian soft power diplomacy” (Tsultrim 2020), along the Himalayas with regard to bilateral relations with Nepal and Bhutan, and further afield with regards to Mongolia.

On the immediate geopolitical front, a belt of Tibetan Buddhist-populated areas under Indian control along the Himalayas overlaps with the disputed sovereignty with China. India claims the Aksai Chin plateau held by China, and China claims Arunachal Pradesh held by India. Meanwhile, the actual border line remains an un-demarcated generally unagreed Line of Control with no substantive talks, let alone agreement, on sovereignty.

Ironies are present, as neither China nor India, be it state and/or government are particularly Buddhist. China is officially an atheist state, underpinned by a materialist ideology (Marxist-Leninism) where religion has been seen as the ‘opium of the masses’, and in which tight party control exerted by Xi Jinping is shaping a nationalistic and increasingly assertive China. Chinese Buddhism may have widespread adherents, albeit in a traditional syncretic symbiosis with Confucianism and Taoism, but is subordinated to tight Chinese Communist Party (CCP) control and direction. Thus, for the Chinese state media, Xi Jinping’s “Buddhism with Chinese characteristics” is a Buddhism to be deployed for the diplomatic glory of the Chinese state, “an asset that can enhance relations with neighbors [….] the glue that can help bond the region under the Chinese dream” (Chen Lijun 2015). China’s regional dream may of course be India’s nightmare?

India’s case is more complicated. Though Shakyamuni Buddha was born in Lumbini (present-day Nepal), his enlightenment came at Bodh Gaya (India), his ministry was along the Ganges plain of India, and he died at Kushinagar (India). A long period of Buddhist ascendancy in India ensued, complete with the glories of Ashoka’s Mauryan Empire and Buddhist expansion from India around Asia. Buddhism was severely critical of Hinduism’s caste system and theistic trappings. Eventually though it was reabsorbed back into Hinduism, the Buddha being recognized as an incarnation (avatar) of Vishnu, but an incarnation bringing a false doctrine (Buddhism) to the demons (asuras), to distract them away from the correct Hinduism. The current BJP presents a tradition of Hindu nationalism domestically fused with a strong India externally. Consequently, the BJP has been very willing to re-invoke the Buddha and his ethics (rather than his theistic critiques of Hinduism) as a figure of “Indian” greatness. Modi’s own stress on Yoga gives another experiential opening to Buddhism, with both being a feature of Indian soft power religiosity.

Beyond its borders, India’s use of Buddhism in its wider neighborhood brings it up against China, similarly engaged in international rise and aspirations in the same strategic backyards, and similarly deploying Buddhism in its diplomacy. Scott profiled this emergent rival deployment of Buddhism in China-India diplomacy in 2016, Ranade talked of Buddhism as “a new frontier in the China-India Rivalry” in 2017, and Raj noted the “resurgence” in their rival Buddhist diplomacy in 2022.

This Indian readiness to deploy Buddhism in its public diplomacy was proclaimed in April 2023, when India’s official Press Information Bureau (PIB) released a substantive booklet entitled Lessons from Lord Buddha. A Collection of Speeches by Hon’ble Prime Minister Narendra Modi. This was a compendium of various speeches from 2014 to 2022 – where Modi extolled the Buddha within India’s general international projection; as well as in his state visits to Sri Lanka, Nepal, Mongolia, Vietnam and Japan. Admittedly, Buddhism was mooted as a feature bringing the two countries together in Modi’s visit to China in 2015, but this linkage has noticeably faded under sharpening regional and immediate border clashes.

Instead, Buddhism has become a sharper competitive tool for India; on show during 2023, with the International Conference on “Shared Buddhist Heritage” in March, the National Conference on the Nalanda Buddhism Tradition in April, the Global Buddhist Summit in April, and the Dalai Lama’s Birthday in July.

The International Conference on “Shared Buddhist Heritage”

This was held in New Delhi, and was organized by India’s Ministry of External Affairs, its Ministry of Culture and its grantee offshoot, the International Buddhist Confederation (IBC).

India’s Ministry of Culture announced the Conference was being held “with focus on India’s civilizational connect with Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) nations.” It was no coincidence that Modi’s own welcoming remarks to the subsequent SCO Summit meeting in New Delhi on 4 July made a point of mentioning the International Conference on “Shared Buddhist Heritage” held in March as a successful initiative by the Indian Presidency during 2023 “to enhance contact” between India and Central Asia. Historically, Buddhism entered Central Asia from India, and Modi’s invocation of such a geo-cultural relationship indicated a readiness to delicately challenge China’s geo-economic presence in the region and indeed the SCO organization.

Admittedly, the language at India’s International Conference on “Shared Buddhist Heritage” was positive. On the geo-cultural front, Zhao Shengliang, the art historian and Director of the Dunhuang Research Institute, argued that that Buddhism was “a huge historic history which brings India and China close” and that “this conference is a message that they are coming together in all aspects, so they will be moving ahead with this peaceful and cultural heritage further”. However, this ignored the ongoing geopolitical and geo-economic friction between the two countries. Indian government officials were perhaps more pointed. The Union Minister G. Kishan Reddy invoked India’s international rise, “India is conducting G20 and SCO meetings, I am hopeful that soon the entire world will receive Lord Buddha’s message.” The Minister of State for External Affairs, Meenakshi Lekhi asserted Buddhism’s Eurasian presence, in which as “India is the centre of this philosophy, ideology, art and culture thus it becomes India’s responsibility to work on it.”

National Conference on the Nalanda Buddhism Tradition

The National Conference on the Nalanda Buddhism Tradition was held at the Gorsam Stupa located at Zemithang, in Arunachal Pradesh’s Tawang district. It was organized by the Indian Himalayan Council of Nalanda Buddhist Tradition (IHCNBT). Zemithang was where the Dalai Lama arrived on fleeing from Tibet in 1959. In a “strong message to China”, the National Conference was attended by leading Rinpoches and Lamas from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, scattered along the disputed Himalayan zones running from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh, as well as scholars and administration officials from India’s varied Himalayan States and districts. Altogether 600 delegates and around 2500 members of the public attended.

Certainly, this was no private event as the delegates were officially welcomed by Arunachal Pradesh’s Chief Minister Pema Khandu, a member of Modi’s ruling BJP, who talked about the state’s diversity but also its strategic importance, geopolitically and geo-culturally. Khandu also tweeted that the Conference “re-establishes the roots of Buddhism to its land of origin Bharatvarsh.” Other non-religious “official” Guests of Honor included a Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) figure (Ulhas Kulkarni), Arunachal Pradesh Legislative Assembly members from Lumla (Tsering Lhamu) and Tawang (TseringTashi), Arunachal Pradesh state officials (Jambey Wangdi, Rinchin Dorjee, Gurmet Dorjey, and Kesang Ngurup Damo) and military figures (Brigadier Vikas Lal).

The IHCNBT had earlier organized a state-level series of Buddhist “Conclaves” in different parts of the Himalayan region between January and March 2021:

- January: Monyul, Arunachal Pradesh Buddhist Conclave

- February: Himachal Pradesh Buddhist Conclave

- March: Uttarakhand Buddhist Conclave

- March: Ladakh Buddhist Conclave

A nudge up came in December 2022 with the “Nalanda Buddhist” Conclave representing a wider “pan-Himalayan” setting, held in Sikkim. The December 2022 Conclave was chaired by the Speaker of Sikkim’s Legislative Assembly, Arun Upreti, with Sikkim’s Minister of Ecclesiastical Department, Sonam Lama, the other guest of honor.

The Indian Himalayan Council of Nalanda Buddhist Traditions (IHCNBT) is an Indian body set up in 2018, on the initiative of the Tawang Foundation, during an earlier Conclave meeting, whose closing function was attended by Kiren Rijiju, then Minister of State of India’s Home Ministry. The IHCNBT is moving to fundee status with India’s Ministry of Culture. Headquartered in New Delhi, the IHCNBT covers the Indian Buddhist districts along the Himalayas, east to west from Tawang, Sikkim, Lahaul-Spiti, Kinaur, and Uttarakhand to Ladakh. Its own website self-definition includes the aim to “instill a nationalist perspective of Nalanda as origin of Buddhism”, and that the “IHCNBT is committed to National integration of Indian Himalayan region.” The IHCNBT Governing Council Meeting for December passed a unanimous resolution against China:

If the government of the People’s Republic of China, for political ends, chooses a candidate for the Dalai Lama, the people of the Himalayas will never accept it, never pay devotional obeisance to such a political appointee and publicly denounce such a move by anyone.

Unsurprisingly, this resolution came 11 days after there was a confrontation between the Indian and Chinese forces at Yangtse in the Tawang district of Arunachal Pradesh.

Global Buddhist Summit

Modi tweeted in April that “inspired by teachings of Lord Buddha, India is taking new initiatives for global welfare.” The context was Modi’s keynote speech at the inauguration of the first Global Buddhist Summit, being held in New Delhi. It was significantly picked up in the Hindu nationalist press, by Swarajya, who did and did not attend Global Buddhist Summit. The Dalai Lama and Taiwan delegates were invited and appeared; China was invited but did not appear. Beijing’s reasons were simple – the appearance of the Dalai Lama, the appearance of Taiwan representatives, and the background border tensions with India.

Modi’s language was unsurprisingly cooperative and expansive, welcoming and irenic.

India stands with humanity in times of every crisis by exerting its full potential. Today the world is watching, understanding and accepting this sentiment of India’s 140 crore people. And I believe that this forum of the International Buddhist Confederation is giving a new extension to this feeling. It will give new opportunities to all like-minded and like-hearted countries to spread Buddhism and peace as a family.

However, such language also implicitly invoked India’s own rise, and its more active diplomacy reaching out to like-minded countries. Modi also made a point in his welcome speech of stressing the Indian initiatives like the development of a Buddha Circuit in India and Nepal, efforts to rejuvenate pilgrimage centers like Sarnath and Kushinagar, the construction of the Kushinagar International Airport for Buddhist pilgrims, and setting up of the India International Centre for Buddhist Culture and Heritage (IICBCH) in Lumbini, Nepal.

The raison d’etre, in other words strategic logic, of the Buddha Circuit is to attract visitors from outside India; in effect “religious tourism as soft power: strengthening India’s outreach to Southeast Asia”, as well as East Asia. Its role in Indian diplomacy was indicated by Modi gaining support for the Buddha Circuit proposal at the BIMSTEC Leaders’ Retreat Outcome Document in October 2016, which recorded “in particular, we [BIMSTEC] encourage the development of Buddhist Tourist Circuit.” BIMSTEC is a particularly useful Indian-led framework linking India to South-East Asia, in which China is not a member. Modi’s speech at the inauguration of the Kushinagar International Airport in October 2021 was also revealing; “India is the centre of devotion, faith and inspiration to Buddhist society around the world”; for which “today, the inauguration of Kushinagar International Airport is in a way a tribute to their devotion.” The India International Centre for Buddhist Culture and Heritage (IICBCH) in Lumbini, Nepal attracted the visit of Modi in May 2022, for its shilanyaas ceremony, with Modi laying its first foundation stone alongside the Nepalese Prime Minister.

Returning to the Global Buddhist Summit, there was widespread recognition in Indian media commentators that through the event India was “using Buddhism as a tool of soft power”, and which was “one more step towards enlarging Indian footprint in Buddhist World.”

The context for Modi’s normative (“like-minded countries”) appeal to the Global Buddhist Summit was an unstated but readily recognizable position of China not being within that circle (of like-minded countries for India). Again, the Indian press was explicit. The Times of India saw the meeting as an Indian attempt generally “to counter China”. Gangadharan reckoned that in underscoring Tibetan Buddhism’s roots in Indian Mahayana Buddhism, the Global Buddhism Summit was a “key step to challenge Chinese narrative on Tibet” and “reflects India’s belated realization that China has seized the narrative on Buddhism with the goal of ‘owning’ it”. Kumar’s take was that “India is reviving Buddhist heritage, standing by Tibet, countering China”, the Conference representing “broader significance in its [India’s] foreign policy, projection of its status, and particularly [his merited emphasis] its efforts to counter China.” China’s reaction, at its Foreign Ministry and in its state media like the Global Times, was to say nothing, to blank the event. Their silence was deliberate and equally telling.

The Dalai Lama’s participation at the India-hosted Global Buddhist Summit in 2023 was also telling. Modi welcomed delegates on the first day, on the second day the Dalai Lama played a prominent role. Given a standing ovation, the Dalai Lama was flanked on the dais by other eminent Buddhists from Bhutan (Padma Acharya Karma Rangdol), Nepal (Shobhan Mahathero), Mongolia (Khamba Lama Gabju Choijamts Demberel), Vietnam (Thich Thien Tan), Sri Lanka (Waskaduwe Mahindawansa Mahanayake Thero) and Burma (Ashin Nyanissara). These are countries targeted by Indian diplomacy.

The Global Buddhist Summit was organized by the International Buddhist Confederation (IBC). The IBC, which is supported by the Indian government and headquartered in New Delhi, traces its origin to the 2011 Global Buddhist Congregation held in New Delhi. China kept away from the 2011 Congregation due to the Dalai Lama’s speaking role there, a boycott repeated at the IBC’s Global Buddhist Summit in April 2023. When New Delhi declined China’s request to exclude the Dalai Lama from the 2011 Congregation, Beijing cancelled the 15th round of border talks between the Special Representatives scheduled for December 2011. The Dalai Lama continues to sit on the IBC official Council of Patrons, alongside other Buddhist figures from Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, South Korea, and Mongolia. China avoids participation in IBC events, instead pushing the five World Buddhist Forum (WBF) settings, held from 2006 to 2018 in China.

The Dalai Lama’s Birthday

Birthday diplomacy was on show in June, when the Dalai Lama sent birthday wishes to India’s President, Droupadi Murmu:

We Tibetans are immensely grateful to the government and people of India for their generosity and kindness to us. As the international community becomes more aware of India’s stature, not only as the world’s largest democracy, but now also as the world’s most populous nation, we feel proud of India’s strength and emerging leadership.

Indeed the Dalai Lama was reported in the Hindustan Times as telling Uzra Zeya, the US coordinator for Tibetan issues, visiting New Delhi on July 10, that he, the Dalai Lama was in effect the “defence minister for India in the Himalayas” and that the “Buddhist community is the frontline defender for India” – the latter point having some truth to it. This was immediately condemned by the Chinese embassy in New Delhi.

Sharply denounced in China, the Dalai Lama continues to be afforded official religious respect by the Indian government. Modi made a point of telephoning and tweeting the Dalai Lama on the Dalai Lama’s 88th birthday, on July 7, 2023, as he had done previously in 2022 and 2021. Modi’s 2021 Birthday greetings were denounced in the Chinese State media, “Birthday greetings to Dalai Lama a futile attempt to show attitude to China.” The following year, Modi’s Birthday greetings to the Dalai Lama was taken up and criticized by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesman who argued that “the Indian side also needs to fully understand the anti-China and separatist nature of the 14th Dalai Lama” and “it [India] needs to abide by its commitments to China on Tibet-related issues, act and speak with prudence and stop using Tibet-related issues to interfere in China’s internal affairs.” Previous to 2021, Modi had last wished the Dalai Lama a Happy Birthday back in 2013, before he took office. Why this particular uptick in 2021, 2022 and 2023? The answer is simple, border conflicts in May 2020 at Galwan, and in December 2022 at Yangtse.

With regard to the Dalai Lama’s Birthday in 2023, what could, indeed undoubtedly did further “rile” Beijing was that the Tibetan Government-in-Exile (TGiE) housed on Indian soil at Dharamshala, also had Hung Sun Han, a member of Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan, as a special guest at its Birthday celebrations held at Dharamshala, as well as the supportive presence there of the Chief Minister of Himachal Pradesh, Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu.

Looking Forward

Border friction and the death of the Dalai Lama are in all likelihood likely to sharpen India’s competitive use of Buddhism in the near future. China of course is increasingly looking to the situation after the Dalai Lama’s death, insisting that the “recognition of new Dalai Lama must be conducted in China.” India’s control of the Buddhist Himalayan centers in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh retains a Tibetan Buddhist zone that is not under Chinese control. Within Arunachal Pradesh, Tawang Monastery (the birthplace of the 6th Dalai Lama) remains a “cultural and strategic flashpoint for Sino-Indian relations”, with particular focus now on Tawang’s future role in enabling a non-China approved Dalai Lama to emerge, on Indian soil.

Whatever the immediate turn of events, in the meantime India’s ongoing deployment of Buddhism utilizes soft power for soft balancing. With Modi on line to win the next General Election, due in June 2024, this “Buddhist” feature of Indian public diplomacy will be maintained.