Militias present as ultra-masculine checks to existing power structures but are steeped in anxiety, paranoia, and conspiracy. Rapidly changing demographics in the United States, compounded with a mainstream rejection of “traditional” masculinity, create ontological insecurity for those who have traditionally topped social hierarchies: white, Christian males. As insecurity rises among this group, they define themselves in opposition to the federal government and seek an idealized past where they feel their social status was secure. Militia narratives and imagery emulate the American Revolution. After finding a fellow freedom fighter in the White House in 2016 and regaining the hyperbolic top of the pyramid, anxiety turned to hubris. Armed citizens like Kyle Rittenhouse used this hubris to cross state lines with firearms and killed two men protesting for racial justice. Rittenhouse was acquitted of all charges (Bosman, 2022). While Rittenhouse is not related to any militia, his actions are in lockstep with a militia’s inward view of heroic vigilantes (Doxsee, 2021). Instead of acting in opposition to the Trump Administration, militias saw themselves as working alongside the institutions they have historically rejected. These four years of exaltation of toxic masculinity came to an end with the 2020 presidential election shifting power to the Democratic Party, which many white male Christians see as an existential threat to their existence. Hubris was again buried by paranoia as armed militia groups like the Proud Boys and 3%ers stormed the U.S. Capitol in a failed attempt to retain security gained under the Trump Administration. In this essay, I aim to explain how ontological insecurity, experienced predominantly by white male Christians, results in hyper-masculine identities that quell anxieties associated with perceived threats to traditional masculine power structures. These anxieties many times lead to paranoid worldviews that are reinforced by right-wing media figures and alt-influencers. I begin this essay with an analysis of the modern militia movement, born out of the Ruby Ridge and Waco standoffs, using the “masculinity curve” to explain peaks and valleys in militia activity. As with many social science theories, the masculinity curve seems to hold steady until Trump comes to office. Under direct orders to “stand back and stand by,” the masculinity market sees an upward shift, increasing levels of masculinity and militia activity (Ronayne and Kunzelman, 2020). Although Trump no longer holds the highest office in the land, the masculinity curve has not shifted back to a pre-Trump equilibrium as malevolent actors prey on ontological insecurity for monetary gains. These heightened levels of toxic masculinities have led to increased revolutionary sentiments and could result in violent outbursts.

Definitions

Masculinity is another term for power in patriarchal societies. When masculinities are threatened, the traditional power structure is threatened. For this essay, threats to masculinity or manhood are considered threats to power — especially for white, Christian men. DiMuccio and Knowles (2020) argue that masculinity is also status in society. Real or imagined loss of status has political ramifications. Some men act within the system to decry feminism and LGBTQ+ rights, while others work outside of the system to construct hyper-masculinized ‘safe spaces’ like militia training camps or online recruitment pages. These sanctuaries of masculinity are kept isolated from perceived others. For example, many militia-affiliated websites are secure, and a screening process is necessary to gain access (Doxsee, 2021). One self-described “constitutional militia” training program, Tactical Civics, requires a “mission oriented phone call” before allowing access to training materials.

I define militia in line with Arie Perliger’s definition found in Cragin (2022: 5), which describes modern, anti-government militias as a collective inspired by right-wing ideology and motivated by “a conviction that it is crucial to counter the increasing powers of the federal government and its tendency to expand into various spheres of the civilian arena.” Militias tend to have no central governing structure but instead consist of loosely affiliated grassroots movements that encompass local communities (Kimmel & Ferber, 2000: 586). The decentralized nature of militias makes them difficult to track, so numbers around active members or frequency of paramilitary training can be difficult to calculate (Ibid.) Despite the overwhelming lack of national or even statewide affiliation of militias, they tend to attract members with similar qualities: white Christian men who are self-described as nationalists and have an overwhelming yearning for an idealized past (Cooter, 2022). This nostalgic yearning “hinge[s] on archetypes of independent, brave men whose heroic efforts were responsible for establishing a nation as these groups wish it to be again” (Ibid.). Paradoxically, these ultra-patriotic white men actively engage with anti-government rhetoric and conspiracies despite claims of upholding the Constitution and protecting American values (Cooter, 2022; Kimmel & Ferber, 2000: 595). Militias fill a gap in perceived loss of power by providing structure and routine to ease anxieties while building like-minded communities that share common goals and interests (Agius et al., 2121: 435). A hyper-paranoid perspective that sees existential threats around every corner is a key characteristic of militias that the literature does not seem to define. However, Doxsee (2021) notes that militia members’ saviour complex is integral to the role they see themselves playing in society and in their local communities — the masculine hero in the looming war of the people versus an encroaching new world order.

The Masculinity Curve and History of Modern Militias

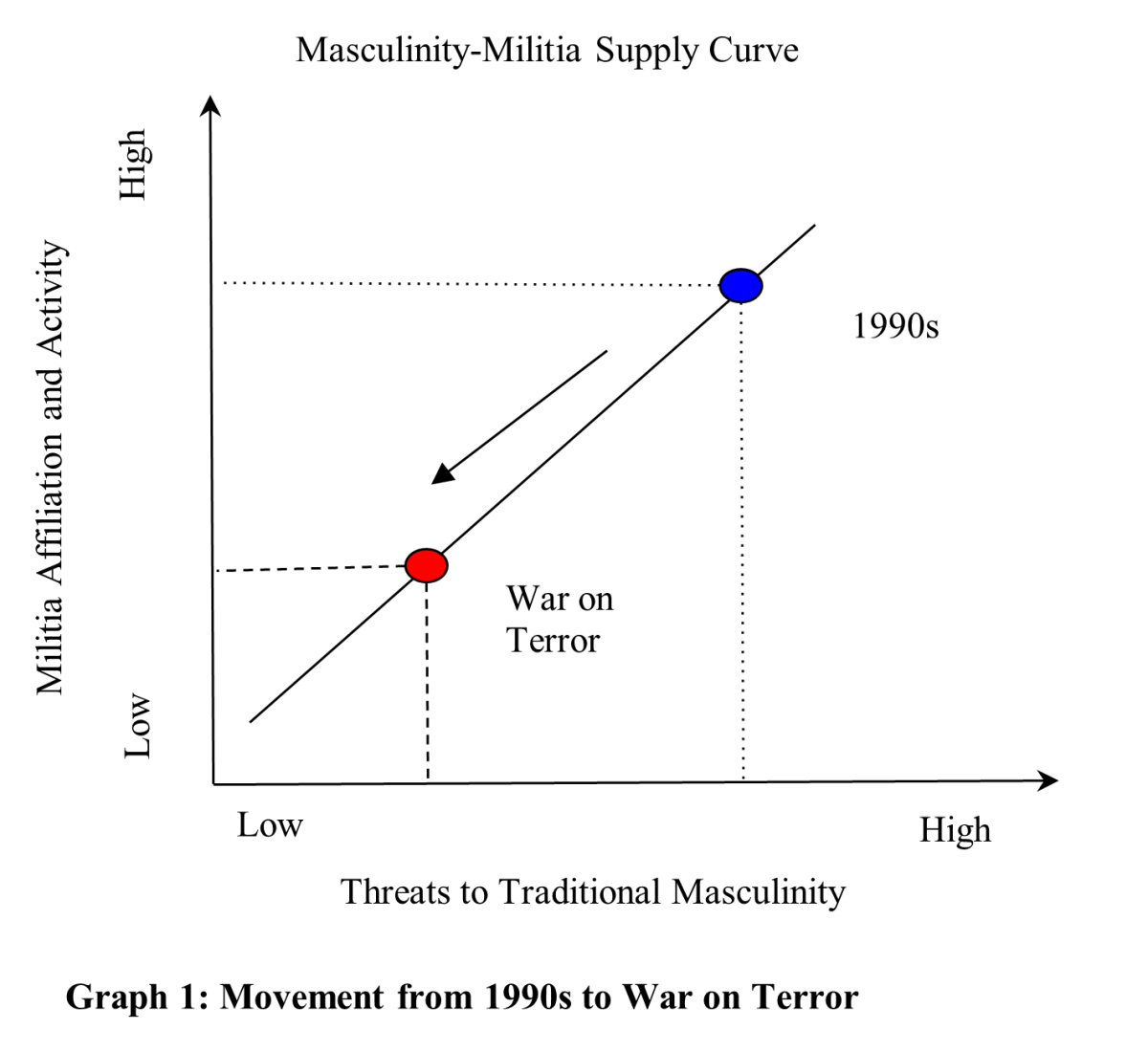

Many scholars mark the beginning of the modern militia movement with the aftermath of the Ruby Ridge and Waco standoffs in the 1990s (Bjørgo and Braddock, 2022; Doxsee, 2021; Mascia, 2022). These standoffs of federal officers against heavily armed civilian groups mixed with the Clinton administration’s passage of the Brady Bill (federal gun legislation aimed at instituting background checks and waiting periods for firearm purchases) and the Federal Assault Weapon Ban saw militia groups peak at an estimated 800 in 1996 (Mascia, 2022). Kimmel and Ferber (2000) argue that gun legislation devalues traditional senses of masculinity as a man feels he can no longer act as a protector of his family (p. 593). But emasculation is not the only factor at play. Restrictive gun laws, perceived overreach by the federal government, and the looming chaos of the millennium bug created a sense of anxiety and imminent danger that traditional holders of power (white Christian men) saw as a direct threat. One manifestation of this anxiety was an influx in militia affiliation and activity, represented by the blue point in Graph 1 (see below Graphs section). Threats to masculinity result in higher output of militias as men attempt to regain a sense of control in traditional masculine roles. The early 1990s spike in militia activity lasted until the election of President Bush, where militia members likely saw solidarity with the conservative White House. Militias largely supported the War on Terror and saw their interest represented in the halls of power (Churchill, 2009: 273). Masculine notions of militarism and heroism reigned supreme, portraying American men as liberators and protectors — this harking back to ideals of American exceptionalism may have put militia members at ease, reducing the need for metaphoric chest pounding. This influx of masculinity in the social and political realm is exemplified by the red point in Graph 1 and resulted in a decrease in militia prevalence. When the supply of threats to masculinity decreases, the price of participating in militia activity seems to be an undue burden. The 1990s surge in militia groups can be understood as a response to anxieties surrounding federal government overreach and perceived violations of the Second Amendment, which manifested in militia affiliation and was later quelled by the Bush Administration.

The second wave of modern militias came from the election of the first Black president of the United States, Barack Obama (Bjørgo and Braddock, 2022). In fact, well-known white nationalists affiliated militia groups, the Oath Keepers and 3%ers, both formed in direct response to Obama’s election (Horton and Giles, 2021). On the campaign trail, Obama discussed the need for stricter gun control, reopening narratives surrounding an overreaching federal government (Doxsee, 2021). Conspiracism moved mainstream as the racist ‘Birther’ movement, spearheaded by Donald Trump, claimed that Obama was not actually born in the U.S. and thus was an illegitimate president sent to undermine true patriots. Racism and conspiracy are two key elements that aided in militia recruitment during the Obama Administration.

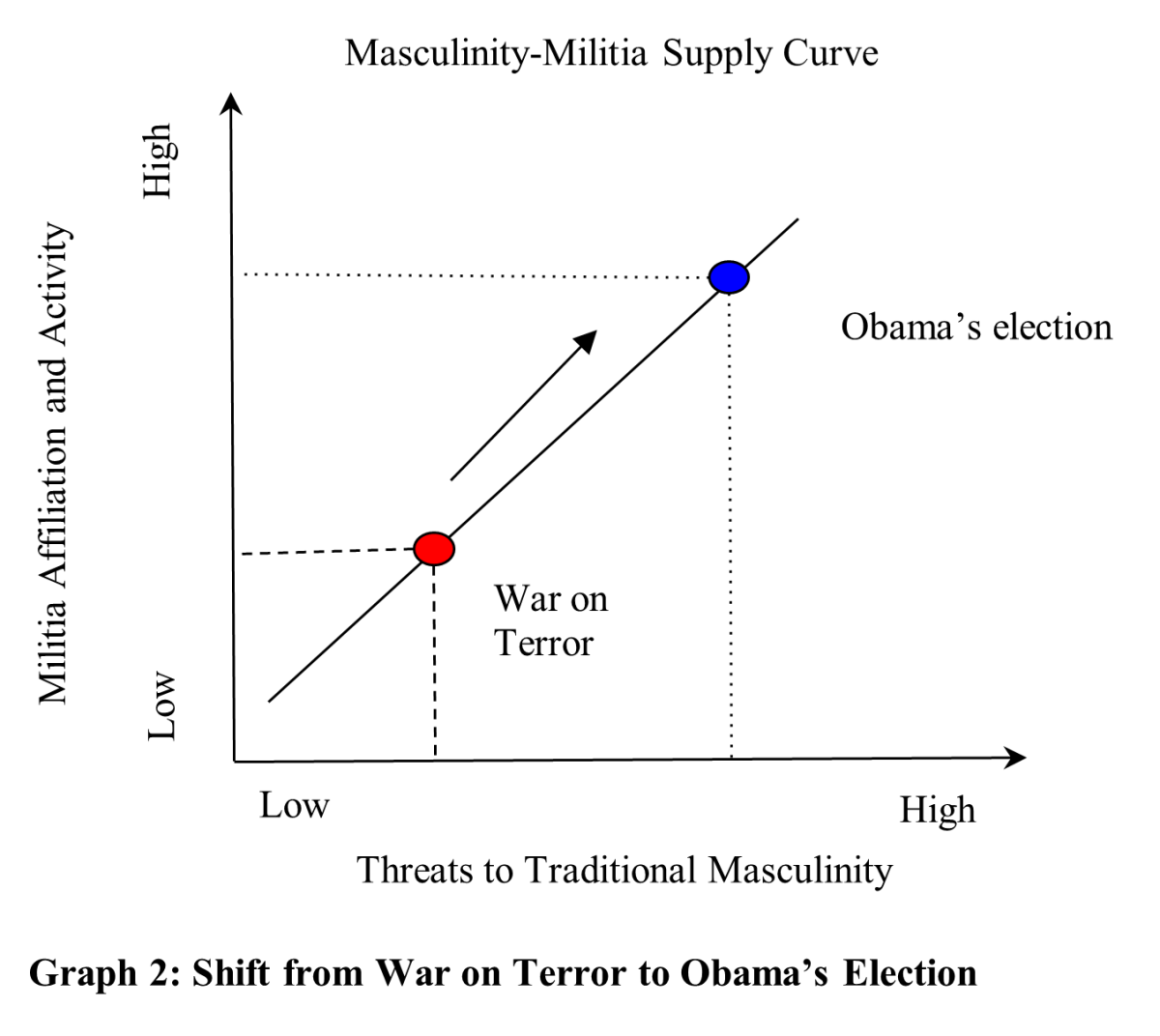

Compounding conspiratorial disdain surrounding Obama’s presidency was the financial crisis and global recession. Garlick notes that the modern notion of masculinity is tied to paid work and the ability of a man to fill the role of a provider (2020: 551). Despite this blatant failure of the capitalist system, militia members overwhelmingly reject condemning the capitalist markets. They see the overarching narrative of a man ‘picking himself up by the bootstraps’ to achieve the American dream as the promise of America and thus reject critique of the economic system that allows this alleged prosperity (Kimmel and Ferber, 2000: 593). According to masculine mentality, capitalism is not the problem, but instead, the federal government is the enemy standing in the way of prosperity. The already hated federal government being led by a Black man for the first time increased anxiety among white men who felt their place in society threatened. As shown in Graph 2, the supply of anxiety and perceived threats to masculinity increased along the militia-masculinity supply curve, causing an output in higher militia involvement than seen under Bush.

Anti-federal government mindsets were not fringe to militia ideology at the time of Obama’s election. The Tea Party, a libertarian-leaning political movement, swept the nation and helped Republicans win the House of Representatives in the 2010 midterm elections (Foley, 2012). The Tea Party, in lockstep with militia ideology, saw the federal government as a bloated, corrupt entity and used the imagery of the Boston Tea Party, where colonists threw tea into the Boston Harbor protesting taxation without representation, to imagine a time when real Americans had power (Doxsee, 2021). Both the Tea Party and Militia movements use nostalgic American imagery to spread their message of a corrupt federal government. Many protestors attended Tea Party rallies dressed in colonial garb while holding signs used as rallying cries during the American Revolution (Walker, 2016). These images are a direct parallel to the colonists’ civil disobedience that served as a precursor to the Revolution.

Modern militia movements continue the tradition of mimicking colonial and revolutionary imagery. Tactical Civics, a self-described “constitutional militia” training and recruitment program, uses the image of a minute man who is roughhousing representations of the Republican and Democratic Parties (Tactical Civics). The image found on the Tactical Civics homepage depicts a minute man with a chiseled jaw and protruding muscles towering over a donkey or an elephant, ready to toss the animals to the proverbial curb (Ibid.). This depiction again reinforces the hypermasculine image that militias attempt to portray to regain perceived lost power. While Obama’s election did increase militia presence, anti-government sentiment and revolutionary imagery took hold in mainstream politics. The Tea Party gave political legitimacy to militia sentiments, setting the stage for the election of Donald Trump.

Born out of a perceived loss of manhood under the Obama Administration, militia members and others on the political right looked for a strong leader to rebalance the historic status quo, placing white Christian men at the forefront of power structures. Republican voters saw in Trump characteristics integral to the U.S. sense of masculinity: success, independence, competitiveness, aggression, and overwhelming confidence (DiMuccio and Knowles, 2020: 25). Trump espoused narratives of an idealized past that galvanized followers to aspire to something ‘great’ again. (Garlick, 2020: 436). This yearning for the past was already present in militia mythology. Take, for example, the 3%ers whose name is based on a false claim that only three percent of the colonists fought the British in the American Revolution (Doxsee, 2021). Trump not only glamorized nostalgia but projected masculinity into the future. One viral video that exemplifies this masculine persona shows Trump single-handedly fighting a cartoon coronavirus in a wrestling ring (Kelly Loeffler, 2020). Trump successfully weaponized narratives about the past to engage future voters and presented himself as a hyper-masculine savior who could restore traditional power structures.

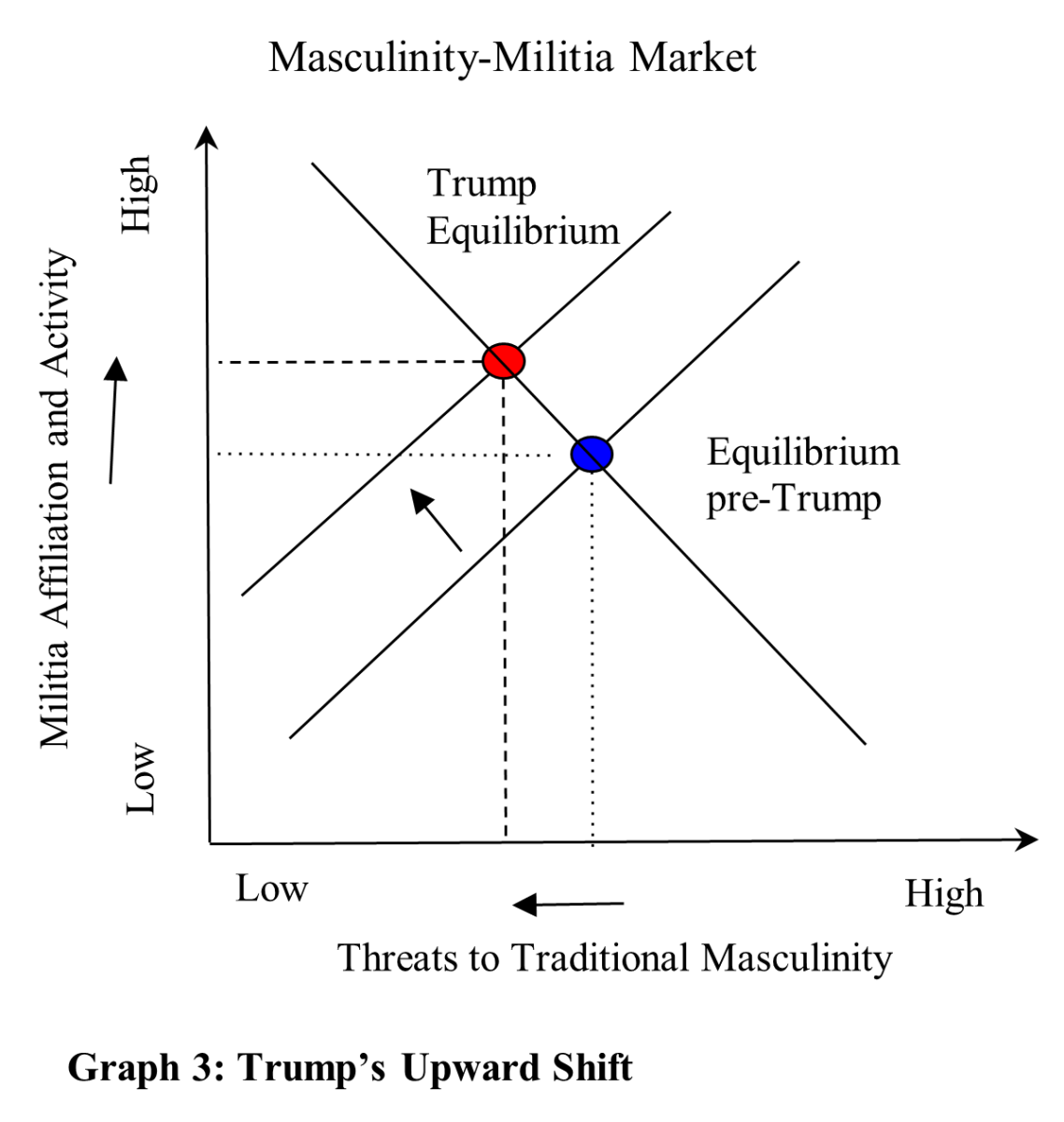

Militia members’ feelings of anxiety moved into feelings of self-grandeur and hubris as Trump re-established a patriarchal power structure favoring white Christian males. Trump’s rhetoric and behavior move away from the situation in Graph 1, where decreases in threats to masculinity simply represent movement along the curve. Here, we see the supply of masculinity shift upward — even though there are fewer threats to masculinity, there is an increase in militia activity. In Graph 1, militia members feel placated eating ‘freedom fries’ while listening to Toby Keith singing about lighting up the Middle East “like July 4” (Keith, 2002). In Graph 3, the president of the United States is instructing white power groups to “stand back and stand by” on national television (Ronayne and Kunzelman, 2020). While not an outright militia, Trump thanked the Cajun Navy during his 2018 State of the Union address, again growing a sense of entitlement among average citizens to work outside of prescribed systems that systematically undermine government (Ezor, 2020: 3, 11). The Cajun Navy, originally founded as a patchwork disaster relief organization, moved to the role of arm protectors after Trump’s shout-out and offered protection to Louisiana synagogues vigilantly after the Tree of Life shooting in Pittsburgh (Ibid: 12).

Trump’s presidency not only served to reinforce militia sentiment but changed the role of militias from fighting the establishment to fighting to reinforce the status quo. Militia members went to the Southern border to maintain order, and some even served as private security for right-wing politicians (Mascia, 2022). Militias typically operate in a top-down military-like structure, but now they are taking orders directly from the commander-in-chief. On March 17, 2020, Trump tweeted “LIBERATE MICHIGAN” in response to Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s Covid lockdown policy (Donald Trump, 2020). Militias took his orders seriously, storming the Michigan capitol just a month after Trump’s tweet (Doxsee, 2021). One group, the Wolverine Watchman militia, took these orders even more seriously and, in October of that same year, plotted to kidnap Whitmer and overthrow the Michigan government (Cooter, 2021). Militias became an ally of the president instead of acting in their traditional adversarial role.

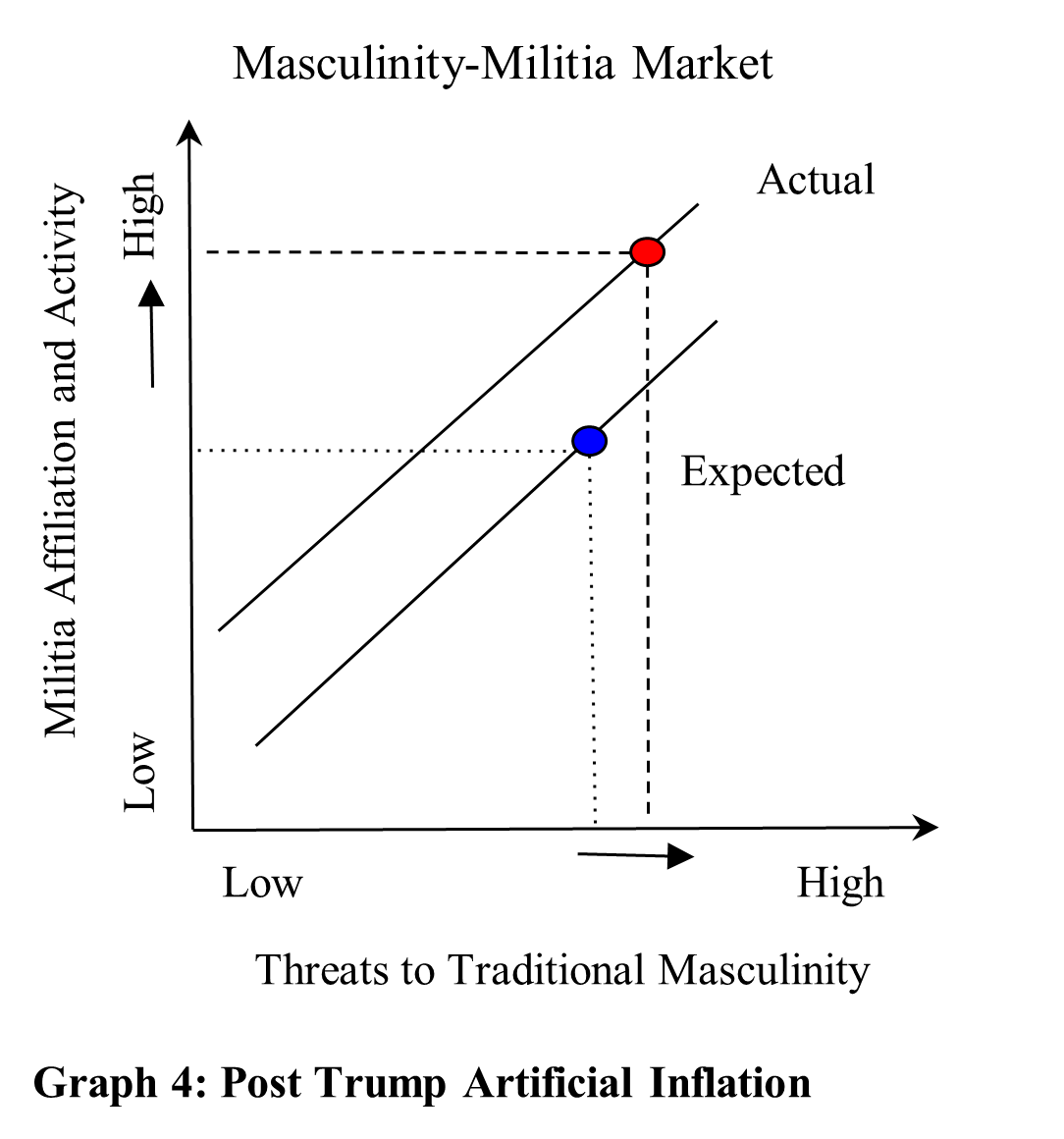

Despite the extreme anxiety that almost surely existed amongst militia members regarding the pandemic, they seemed to find comfort in integrating into existing extremist communities. Weinberg and Dawson (2021) note that anti-government militia men coexisted on Facebook groups with anti-vaccination ‘activists’ and Q-anon supporters who all shared grievances regarding the degradation of civil liberties. These online conspiratorial groups brought about a sense of collectivism, seemingly antithetical to the traditional militia values of individualism and independence (Agius et al., 2021: 438). Collectivism in online echo chambers and a feeling of loyalty to their freedom fighter explain why these groups came to the beckoned call of Donald Trump on January 6, 2021, to alter the outcome of the 2020 election. The House of Representatives Select Committee on January 6th noted that many right-wing, white-nationalist militias were partially responsible for the organization and execution of the storming of the Capitol (House of Representatives, 2022: 55-56). The events of January 6 represent the militia’s attempt to hold onto power by keeping their freedom fighter in the White House. It is difficult to determine what movement may occur on the masculinity curve post-January 6th, but it is logical that the supply curve would shift to pre-Trump equilibrium before increasing along the x-axis as there are perceived threats to masculinity. As explored in the next section, this logic does not hold. Alt-right influencers and media figures like Tucker Carlson are aiming to artificially inflate the market to keep equilibrium at Trump equilibrium (see Graph 3) for financial and political gain. With the market at Trump-equilibrium, threats to masculinity again increase along the x-axis, causing the highest output of militia activity thus far (see Graph 4).

Filling the Masculinity Vacuum

Militias and other right-wing ideologues’ attempts to maintain power structures on January 6 were fruitless, but this vacuum of masculinity for the right, after a period of thriving, gave way to an enhanced online presence for alt-right influencers. Horton and Giles (2021) quote Freddy Cruz of the Southern Poverty Law Center, who notes, “[a]nti-government extremist groups try to capitalize on [feelings] of instability by selling an image of structure, stability and camaraderie […].” Many militia movements have remained underground or operate behind secure channels as the Biden Administration has taken a more stringent stance on anti-government activity post-January 6th, so it can be difficult to track recruitment at this particularly unstable moment for militias (Cooter, 2022). But alt-right influencers are keen to build loyal online communities by filling the masculinity gap and co-opting feelings of instability for monetary gain.

Rumble, a right-wing video-sharing platform, hosts videos from user michaelj5326, also known as Michael Jaco. Jaco’s videos utilize intentionally inflammatory titles that would seem to elicit responses from militia members or others who hold similar ideologies. Two video titles from Jaco’s channel stand out for specific mention of militias: “It’s your constitutional right to form and belong to a militia. The time is Now! as sleeper cells throughout the world are being activated” and “We the people are “The Storm” and Tactical Civics along with Constitutionally focused militias are unstoppable and will take back the Republic of America.” As of April 13, 2023, Jaco has 103k followers, and both videos have nearly reached 30,000 views each. The content of the videos is what one might expect from the titles: conspiracy, fear-mongering, and framing oppressed Christian white men as patriots who must save a deteriorating nation. The videos appeal directly to men who are disillusioned by the government and feel threatened by changing gender roles and power structures (Kimmel and Ferber, 2000: 585). Viewers no longer have Trump as the pinnacle of masculinity. Influencers, masquerading as freedom fighters and truth tellers, attempt to fill the gap by appealing to a nostalgic, traditional masculinity that mimics militia sentients.

In addition to being an alt-right podcaster, Michael Jaco claims to be a former Navy Seal, CIA security contractor, and spiritual guru. His background makes him an ideal figure in right-wing alt-media. Jaco’s far-right Rumble channel links to his website where he sells merchandise, calling on followers to “stay in the vibrations.” Followers can even purchase a bundle of his alleged ‘self-help’ courses for $2,616 (Ultimate Course Bundle). In addition to purchasing online self-help courses, Jaco offers members exclusive access to his private social media platform, the “intuitive warrior community,” for $14.95 a month. Jaco seems to use the facade of right-wing radicalism and the co-option of his military background to funnel loyal followers into wellness programs to make a profit off hate speech and conspiracism. He highlights masculine roles as a Navy Seal and CIA contractor to attract people like militia men who feel disillusioned about current trends in geopolitics and their place in society. Jaco is selling an enlightened yet traditional masculinity to profit off of political and social grievances.

One other alt-influencer we will discuss is Patriot Streetfighter (Scott McKay), who has appeared on Jaco’s podcasts. Patriot Streetfighter describes himself as “a highly censored combat machine taking on the battle against the deep state global power structure on behalf of “We The People” according to the homepage on his website (Patriot Streetfighter- Scott MacKay). In addition to wartime verbiage, Streetfighter utilizes militia imagery to further sell himself as a hyper-masculine risk-taker working outside the system for the common people. From images on the Streetfighters homepage, Streetfighter is portrayed as a muscular man in tactical gear holding the Constitution as a weapon. A patch in the middle of his chest is also notable — at first glance, the yellow rectangle appears to be the Gadsden flag. The Gadsden flag was originally created as an anti-British revolutionary flag, but in recent times, it has been used in right-wing protests to call out perceived government overreach (Walker, 2016). Upon closer analysis of the image, the rattlesnake is not coiled but instead in the shape of a Q, showing support for Q-anon. Iconic American imagery, conspiracy, and militantism coalesce in Streetfighter’s persona to portray a freedom-fighting figure who is protecting traditional masculinity and power structures.

While Streetfighter’s website stays more on brand with his espoused right-wing conspiracism than Jaco’s’, he also uses his online following of insecure men for monetary gain. One of his business endeavors is promoting a $175.00 limited edition magazine portraying Former President Trump as a minuteman from revolutionary times, which further appeals to militia members with seditious sentiments (GEORGE Magazine). Like Jaco, Streetfighter began his career as an entrepreneur in the “wellness” industry. While Garlick (2020) notes that the entrepreneurial spirit of the self-made man is a key narrative in masculinity, it appears these influencers are using entrepreneurial ingenuity to fill the vacuum of masculinity in the marketplace after Trump’s loss. Increased anxiety means these influencers can build followings and make additional profit by exploiting perceived loss in power post-2020. Using nostalgia for revolutionary times and hyper-masculine caricatures is one way influencers show solidarity with militia men to gain their trust and loyalty.

Fringe alt-influencers are not alone in hijacking anxiety stemming from a perceived loss of masculinity. The head of the Republican National Committee, Ronna McDaniel, recently announced that Rumble would have exclusive rights to live-stream the first 2024 Republican primary debate (Chiacu, 2023). Streaming such a consequential event on a site that hosts influencers openly pushing conspiracy and seditionist sentiments will likely lead to boosts in engagement for these content creators. This will further encourage influencers to continue the cycle of producing inflammatory content (painting a world where white, Christian men are existentially threatened) to increase anxiety and drive traffic to their websites. The Tucker Carlson effect can also not be understated. Before being fired from Fox News, Carlson had the most-watched prime-time cable show. His audience was predominantly white Christians, and Carlson routinely painted traditional American values as under threat from a shadowy elite (Yourish and Buchanan, 2022). These actions directly correlate to the artificially conflated supply of masculinity in the marketplace for masculinity (see Graph 4). People believe they are under attack and thus flock to militias to secure the traditional American values, particularly masculinity, that they are desperate to save. These deep-seeded beliefs of an unfair system and lack of power have resulted in the slogan “Trump ‘24 of Before” on bumper stickers and other campaign materials, implying working outside of the democratic process to bring Trump back to power (Official Everything Woke Turns To Shit Flag 5’x3’). “Trump ‘24 of Before” as a marketing tool continues the trend of targeting groups like militias that idolize revolution as many iterations use imagery of the post-revolution American Flag. Threats to masculinity are openly discussed in the mainstream, and right-wing intellectuals are seemingly driving anxiety for political gain.

Conclusion

From the modern iteration of militias in the 1990s through today, ontological insecurity exists because of perceived changes in power relations that have historically benefited white Christian men. In a quest to quell these feelings of anxiety and paranoia, militias form, recruit, and engage in civil society. Militias provide a sense of collective security, comradery, and control for members. This security is covered in a blanket of traditional masculinity that allows members to tap into and emulate the Founding Fathers’ key traits of “individualism, fearlessness, [and] rebellion” (Cooter, 2022). Historically, militia activity follows the logic of an upward-sloping curve. When perceived threats to masculinity increase in civil society, militia activity and recruitment duly increase. This correlation remained constant until Trump’s 2016 victory when militias no longer acted as checks to government power but instead acted to reinforce Trump’s worldview. Militia anxiety manifested as hubris. A single curve is no longer appropriate for analysis as Trump’s actions and rhetoric shifted the supply of masculinity in the market, allowing for increased militia activity during a time when traditional notions of masculine power dominated. The four years of the Trump presidency ended, leaving militias again feeling threatened, but the market did not course correct. Instead, right-wing media and alt-influencers have filled the void by spreading conspiracy and using revolutionary iconography to co-opt militia members and far-right ideologues. These figures feed on existing ontological insecurity among militia members to increase ratings or sell products. Increasing inflammatory rhetoric in the mainstream (especially rhetoric that appeals to heavily armed groups with a keen eye for revolution) may manifest itself outside of the political arena. Masculinity as an antidote to insecurity may result in militia members taking rallying cries like “Trump ‘24 or Before” literally in a continuation of political violence from January 6.

Graphs

Bibliography

Agius, C., Rosamond, A.B. and Kinnvall, C. (2020) ‘Populism, Ontological Insecurity and Gendered Nationalism: Masculinity, Climate Denial and Covid-19’, Politics, Religion & Ideology, 21(4), pp. 432–450. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2020.1851871.

Bjørgo, T. and Braddock, K. (2022) ‘Anti-Government Extremism: A New Threat?’, Perspectives on Terrorism, 16(6), pp. 2–8.

Bosman (no date) Kyle Rittenhouse Acquitted on All Counts – The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2021/11/19/us/kyle-rittenhouse-trial (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Chiacu, D. (2023) ‘Republicans set first 2024 U.S. primary debate for August in Milwaukee’, Reuters, April 12. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/us/republicans-set-first-2024-us-primary-debate-august-milwaukee-2023-04-12/ (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Churchill, R.H. (2009) To Shake Their Guns in the Tyrant’s Face: Libertarian Political Violence and the Origins of the Militia Movement. Ann Arbor, UNITED STATES: University of Michigan Press. Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gla/detail.action?docID=3414934 (Accessed: April 11 2023).

Cooter, A. (2022) Citizen Militias in the U.S. Are Moving toward More Violent Extremism, Scientific American. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0122-34.

Cragin, R.K. (2022) ‘Virtual and Physical Realities: Violent Extremists’ Recruitment of Individuals Associated with the US Military’, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, pp. 1–22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2022.2133346.

DiMuccio, S.H. and Knowles, E.D. (2020) ‘The political significance of fragile masculinity’, Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, pp. 25–28. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.11.010.

Donald J. Trump [@realDonaldTrump] (2020) ‘LIBERATE MICHIGAN!’, Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1251169217531056130 (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Doxsee, C. (2021) Examining Extremism: The Militia Movement, CSIS. Available at: https://www.csis.org/blogs/examining-extremism/examining-extremism-militia-movement (Accessed: April 3 2023).

Ezor, Z. (2020) “‘Calling Forth’ The Cajun Navy? Legal Frameworks for Ad Hoc Disaster Relief,” Duke Law Center on Law, Ethics, and National Security, pp. 1–28. Available at: https://law.duke.edu/sites/default/files/centers/lens/Ezor_Cajun_Navy_Formatted_w_Cover.pdf (Accessed: 2023).

Foley, E. (2012) The Tea Party: three principles, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Available at: https://lccn.loc.gov/2011040843 (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Garlick, S. (2020) ‘The nature of markets: on the affinity between masculinity and (neo)liberalism’, Journal of Cultural Economy, 13(5), pp. 548–560. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2020.1741017.

GEORGE Magazine. GEORGE Magazine INDEPENDENT and AUTONOMOUS (no date). Available at: https://georgeonline.com/product/george-issue-1-version-2-0-commemorative-edition/ (Accessed: April 14 2023).

House of Representatives, Congress. (2022). Final Report of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol. [Government]. Government Publishing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-J6-REPORT/ (Accessed: January 6, 2023).

Horton, J. and Giles, C. (2021) ‘Capitol riots: Are US militia groups becoming more active?’, BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-55638579 (Accessed: April 3 2023).

It’s your constitutional right to form and belong to a militia. The time is Now! as sleeper cells throughout the world are being activated. (no date). Available at: https://rumble.com/v2bi2zc-its-your-constitutional-right-to-form-and-belong-to-a-militia.-the-time-is-.html (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Keith, T. (2002) Courtesy of the Red White and Blue (The Angry American).

Kelly Loeffler [@KLoeffler] (2020) ‘COVID stood NO chance against @realDonaldTrump! https://t.co/GtNPOHkDqF’, Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/KLoeffler/status/1313201217309417478 (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Kimmel, M. and Ferber, A. (2000) ‘“White Men Are This Nation:” Right-Wing Militias and the Restoration of Rural American Masculinity’, Rural Sociology, 65(4), pp. 582–604.

Mascia, J. (2022) Are Militias Legal?, The Trace. Available at: https://www.thetrace.org/2022/04/militias-legal-armed-demonstration/ (Accessed: March 29 2023).

Michael K Jaco (no date) Michael K Jaco. Available at: https://michaelkjaco.com/ (Accessed: April 14 2023).

“Official Everything Woke Turns To Shit Flag 5’x3’.” n.d. Trump Swag. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.trumpswag.com/product/woke/23.

‘Patriot Streetfighter – Scott MacKay’ (no date). Available at: https://patriotstreetfighter.com/ (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Ronayne, K. and Kunzelman (2020) Trump to far-right extremists: ‘Stand back and stand by’, AP NEWS. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/election-2020-joe-biden-race-and-ethnicity-donald-trump-chris-wallace-0b32339da25fbc9e8b7c7c7066a1db0f (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Tactical Civics (no date). Available at: https://tacticalcivics.com/ (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Ultimate Course Bundle (no date) Unleashing Intution. Available at: https://unleashing-intuition1.teachable.com/p/unleashing-intuition-secrets-course-bundle (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Walker, R. (2016) The Shifting Symbolism of the Gadsden Flag | The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-shifting-symbolism-of-the-gadsden-flag (Accessed: April 14 2023).

We the people are ‘The Storm’ and Tactical Civics along with Constitutionally focused militias are unstoppable and will take back the Republic of America. (no date). Available at: https://rumble.com/v2ceb9q-tactical-civics-along-with-constitutionally-focused-militias-are.html (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Weinberg, D. and Dawson, J. (2020) From Anti-Vaxxer Moms to Militia Men: Influence

Operations, Narrative Weaponization, and the Fracturing of American Identity. preprint. SocArXiv. Available at: https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/87zmk.

Who are the Tea Party activists? – CNN.com (no date). Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2010/POLITICS/02/17/tea.party.poll/index.html (Accessed: April 14 2023).

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Crisis or Continuation? The Trump Administration and Liberal Internationalism

- How Does Hegemonic Masculinity Influence Wartime Sexual Violence?

- On Memes and Men: How Gendered Memes Influenced Trump’s 2016 Election Legitimacy

- Two Nationalists and Their Differences – an Analysis of Trump and Bolsonaro

- Offensively Realist? Evaluating Trump’s Economic Policy Towards China

- On Reagan’s Legacy: A Comparison with Trump and Biden