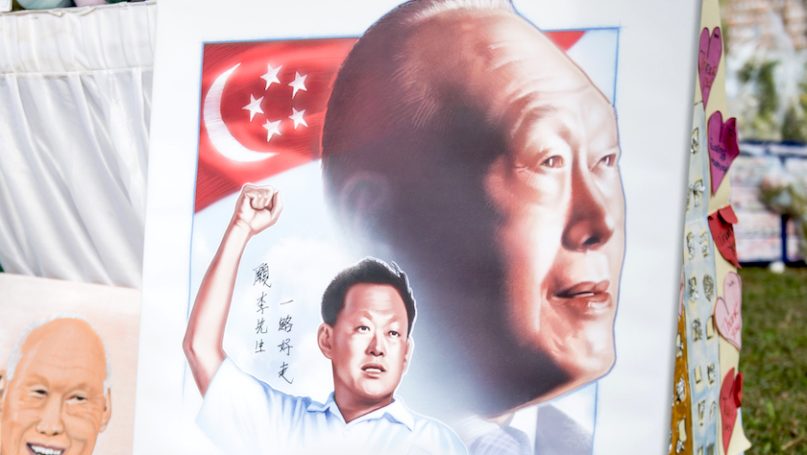

Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s founding father, would have celebrated his centenary on 16 September 2023. There has been a spade of articles commemorating the occasion (see e.g., Han 2023; Chua 2023; Koh 2023), but commentators have missed the opportunity to highlight how the study of Lee Kuan Yew’s political thought can potentially contribute to more scholarly understandings of international affairs. While Lee’s foreign policy thought has received scholarly attention (Ang 2023; Allison et al. 2013), the foundations of this thought, best approached as political theory, has not been adequately unpacked (c.f. Quah 2022; Barr 2000). A clue can be discerned by how in August 2023, the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) commemorated Lee Kuan Yew’s 100th with an event themed “Reinventing Destiny.” This theme astutely gestures at an under-explored motif within Lee’s political philosophy —the role of history.

How Lee approached the subject of history, or his overarching philosophy of history, is foundational to Singapore’s self-identification, and thereby brings considerable downstream implications for its policies and overall approach to international affairs. Surveying his speeches and writings over his lifetime, one can begin to sketch out Lee’s complex philosophy of history. This can be summarized as the recovery of the agency of small states like Singapore amidst the broader tides of History. Here, “history”, or History with a capital H, is understood in a specific sense. It is often recognized to be rooted in the philosophical thinking of German philosopher, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (see Duquette 2019).

Observing world-shaking events like the French Revolution, Hegel sought to understand the character and influence of history, and how it would develop. He eventually understood history not as a series of randomly unfolding events, but as a purposeful, rational process. History needed to be understood holistically, encompassing the entire world. Participants of History were those that helped to move this process forward. This is where standard understandings of phrases like “history is on our side” can be traced back to. It is this understanding of history that subtly lies behind the theme of “Reinventing Destiny.”

Lee’s engagement with this conception of History, which shaped his own thinking about the issue, can be exhibited in three key episodes. The first episode occurred during the Japanese occupation of Singapore, as part of the Second World War. It was at this moment that key narratives about aptness of Western colonial rule had been shattered. Colonial rule was predicated on narratives of racial hierarchy, where White Anglo-Saxons were predestined to lord over Asians. These narratives were themselves predicated on understandings of History. Hegel had infamously wrote that Asians had “no History,” meaning that Asians were incapable of spurring progress and thereby not participants in History. Instead, White Anglo-Saxons were to bring History to Asia through colonization.

The myth of British or White superiority was left unchallenged by Lee until the Japanese handily unseated British power in Singapore between 1942 and 1945. This stimulated Lee to develop a contrary view, where Asians were also capable of affecting the Historical process (Lee 1998). By understanding Asians as Historical agents in their own right, Lee began to reject narratives of colonial rule and developed anti-colonial sympathies.

The second episode occured at the height of the process of decolonization, in the decades following the end of World War II. This was a period where the ideas of Hegel’s most prominent follower, Karl Marx, were in high currency, given communism’s anti-colonial credentials and its promise of a rapid road towards modernity. Many Marxists throughout the 20th century had imbibed the idea that history’s purposeful ending was imminent, after the overthrow of the capitalist system of production. This “End of History” would be a classless society without exploitation. These Marxists sought to shift this process along, playing the role of History’s handmaiden (Christie 2000).

While not a Marxist per se, Sukarno, Indonesia’s founding father and anti-colonial revolutionary, was greatly influenced by these ideas and adapted it to his thinking. For Sukarno, the complete eradication of colonial or neo-colonial patterns of domination would inevitably usher in a particular vision of the “End of History” – an international system based on peace and bereft of conflict, what he once described as “Pax Humanica” (see McIntyre 2005). He had earlier counseled the United Nations to not be “blind to history, to ignore destiny.”

These ideas fed into the narratives surrounding the different paths and conceptions of decolonization, of which Lee was an active participant. This can most clearly be seen during Konfrontasi, when Indonesia had accused the formation of Malaysia in 1963 as a neo-colonial plot and waged an undeclared war to stunt its formation. While Konfrontasi is commonly understood in the category of security (e.g. Jones 2001), the event was justified by arguments with considerable philosophical undertones, and it is worth examining how those arguments legitimized the military action.

Narratives, like Sukarno’s, that justified military exercises against neo-colonialism were rejected by Lee as idealistic romanticism, or an “oversimplified view of socialism” (Quah 2022). Lee proclaimed amidst Konfrontasi that Asians were “human beings, just like the others, as much prisoners of their past as apostles of their future” (Christie 2000). Importantly, countries like Singapore whose survival was not guaranteed, could ill-afford to be seduced by such a vision, as it blinded them from the cruel but persistent realities of international politics. Instead, states like Singapore needed to be clear-eyed and engage in realpolitik. History was no savior.

While the idea is not new, the phrase the “End of History” was coined by American political scientist Francis Fukuyama (1989), based off his reading of Hegelian philosopher Kojève. Fukuyama had famously argued that the end of the Cold War had debunked the Marxist project. Instead, the “End of History” was the proliferation of American-style liberal democracy, which nation-states around the world would inevitably conform to. This was the context from which Lee launched the “Asian Values” debate (see e.g., Barr 2002). Briefly, Lee and others argued that different societal traditions and expectations meant that political arrangements apart from US-style liberal democracy were just as viable. Therefore, this third episode was where Lee contested the idea that History had to culminate in a singular end point. Instead, different nations could choose their own diverging paths.

Overall, Lee observed that History does not have a predestined end, nor does it prescribe a foregone conclusion. How world affairs develop is ultimately up to the choices humans make—history is not its own author. This approach towards History underpinned Lee’s vision of a Singapore that could exercise its agency within international affairs despite the limitations of size. This thinking has been passed down to both political leaders and public intellectuals in Singapore, as Ministers Chan Chun Sing and Lawrence Wong consistently reference that Singapore has to continue to “defy the odds of history.”

This philosophy been subtly passed down and deeply imprinted into the thinking of many generations of Singaporeans, especially its elite (see Kausikan 2017). That has ensured a continuity of thinking in how Singapore sees itself within the constellation of international politics, and therefore how it exercises its foreign policy. In that way, even in his death, Lee’s influence lives on. Academics might consider exploring how his writings and speeches might provide useful scholarly material, and a fruitful means to explore the nexus of intellectual history and international relations (see Nardin and Bain 2017; Bell 2023).

References

A. McIntyre. (2005). The Indonesian Presidency: The Shift from Personal toward Constitutional Rule. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.

Allison, G., R. Blackwill., and A. Wyne (2013). Lee Kuan Yew: The Grand Master’s Insights on China, the United States, and the World. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ang, C. G. (2023). Reassessing Lee Kuan Yew’s Strategic Thought. London: Routledge.

Bain, W. and T. Nardin. (2017) ‘International relations and intellectual history’. International Relations 31 (3): 213–26.

B. Kausikan. (2017). Singapore Is Not An Island: Views on Singapore Foreign Policy. Singapore: Straits Times Press.

C. Christie. (2000). Ideology and Revolution in Southeast Asia 1900-1980. London: Routledge.

Chua, M. H. (2023). “Lee Kuan Yew at 100: Taking Singapore beyond the LKY legacy”. The Straits Times. www.straitstimes.com/opinion/lee-kuan-yew-at-100-taking-singapore-beyond-the-lky-legacy

D. Bell. (2023). “International Relations and Intellectual History”, in The Oxford Handbook of History and International Relations (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 94-165. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198873457.013.7.

D. Duquette. (2019). ‘Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Philosophy of History’. Oxford bibliographies. DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195396577-0133.

F. Fukuyama. (1989). ‘The End History?’ The National Interest 16 (Summer): 3-18.

Han, F. K. (2023). “Commentary: Singapore was built on Lee Kuan Yew’s ideas – which are still relevant today and which are not?” Channel News Asia. channelnewsasia.com/commentary/lee-kuan-yew-100-birth-anniversary-founding-prime-minister-nation-building-3767001

Jones, M. (2001). Conflict and Confrontation in South East Asia, 1961–1965: Britain, the United States, Indonesia and the Creation of Malaysia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee. K. Y. (1998). The Singapore Story. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish.

M. Barr. (2000). Lee Kuan Yew: The Beliefs Behind the Man. Georgetown: Georgetown University Press.

M. Barr. (2002). Cultural Politics and Asian Values: The Tepid War. London: Routledge.

Quah, S. J. (2022). ‘“Technocratic Socialism”: The Political Thought of Lee Kuan Yew and Devan Nair (1954–1976)’. Journal of Contemporary Asia 53 (4): 584-607.

T. Koh (2023). “Remembering Lee Kuan Yew on his 100th birthday”. The Straits Times. www.straitstimes.com/opinion/remembering-lee-kuan-yew-on-his-100th-birthday

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Reflections on Decoloniality, Time, History and Remembering

- The Mandala, Agency and Norms in Indonesia-India Global Affairs

- War and Imperialism in the Aerial History of World Politics

- Opinion – Rethinking History in Light of Ukraine’s Resistance

- A Defence of Macro-History in International Relations

- Dashing Lines and Faking History: The Complicated History of Taipei’s Maritime Claims