In 2023 alone, President Biden has met with four Latin American countries led by left-wing governments, including Argentina, Mexico, Bolivia, and Colombia. Considering the historic tendency of the US to support the right in Latin America, what could these meetings signal towards the future of Latin American-US relations? Relationships between the United States and its southern neighbors have been historically marked by U.S. interventionism in the region, particularly during the Cold War. The Cold War (1947-91) was a moment in history that was marked by simultaneous increase in panic over left-wing ideologies like communism and socialism along with new trends toward globalization in the United States. Truman argued that it was no longer safe to simply depend on the security of US territory for national safety, but rather it now depended on stopping the expansion of Soviet totalitarianism and defending those states that could be corrupted. This vision of interventionism led to the Truman Doctrine. As a result, U.S. interference in Latin American countries increased, with the primary aim of combatting the possible involvement with the Soviet Union in the region as well as the spread of leftist ideologies in respective Latin American governments. This US perspective toward Latin America is one that has been slow to change.

Histories of United States Interventionist Policies

During the ‘banana republic’ era, this intervention took on a more capitalistic approach. US interventions sought to replace democratically elected left-wing governments with those that were more sympathetic to U.S. interests, particularly U.S. business interests abroad. In Guatemala, for example, the U.S. government backed a military coup aimed at overthrowing the democratically elected President Jacobo Arbenz. In 1951, Guatemala held their first democratic presidential election in which Colonel Jacobo Arbenz was elected. However, some of Arbenz’s policies directly threatened U.S. business interests and profit in the country. The Arbenz Administration had introduced Decree 900, which outlined a progressive stance on wages and land reform, which threatened the profit structure of the United Fruit Company, a privately-owned, U.S.-based company. The U.S., seeing this as a threat, involved the CIA in a covert operation during which they armed, trained, and funded the Guatemalan military. The military then overthrew the Arbenz administration. Following the coup, Guatemala remained under a military dictatorship for multiple decades, during which time resulted in the genocide of Indigenous Mayan people in Guatemala in the 1980s. The search for the disappeared is still ongoing in Guatemala today.

Following U.S. intervention in Guatemala, the National Security Council wrote a report in which they outlined the objectives and focus of U.S. policy toward Latin America. In particular, they outline the important role that Latin American had in the Communist expansion era. It reads: “A defection by any significant number of Latin American countries over their governments, would seriously impair the ability of the United States to exercise effective leadership of the Free World […] and constitute a blow to U.S. prestige.” The National Security Council explicitly outlined the need for respect, partnership, and cordiality with other countries in the Americas. However, the report includes a clause which states that they shall recognize Latin American governments “unless a substantial question should arise with respect to Communist control.” This report and subjective quote created leeway and a policy justification for the U.S. to continue to implement policies of interventionism in their ‘own backyard.’

From here on, the U.S. continued to intervene in various Latin American countries and contexts. In Colombia, the U.S. assisted the Colombian government with the threat that leftist guerrilla groups like the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) posed through Plan Colombia and Plan Patriota. In Argentina, they turned a blind eye to the “Dirty War” that happened in the late 1970’s through the early 1980’s. In Bolivia, various U.S. administrations participated in covert operations throughout the 1960’s. In Chile, they used covert actions to fund electoral candidates, “run anti-Allende propaganda campaigns and had discussed the merits of supporting a military coup,” in the 1960’s and 70’s. We can look to Cuba, where the U.S. participated in both covert and overt operations in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Last but not least in El Salvador, the U.S. funded and trained paramilitary groups that caused unrest and violence in the 1960’s. Most countries in the region had their trajectories of governance altered by U.S. intervention, which continues to have implications for today’s foreign policy discourses and decisions.

Implications for Foreign Policy Today? The TRIP Survey Project

With this troubled context of U.S. interventionism in mind, we asked U.S. policymakers how they felt about the progressive wave of administrations recently elected in Latin America. Based on our results, it seems that bureaucrats and technocrats within the U.S. government are no longer particularly concerned over a perceived “leftist threat” in the region. However, that change in attitude is not necessarily shared by many officials in Congress.

Over the last twenty years, the Teaching, Research & International Policy (TRIP) project, based in the Global Research Institute in the College of William & Mary, has surveyed international relations (IR) experts, policymakers, and think tank experts based in the U.S. Our surveys are focused on asking these experts their views on foreign policy trends. In the most recent survey (October 2022- January 2023) we asked: ‘How likely is it that the wave of left-wing administrations recently elected in Latin America will threaten U.S. strategic interests in the region?’ We wanted to see if there had been any change in sentiment towards the Latin American leftist governments in U.S. policy, considering the Biden administration’s meetings and rising concerns of China’s influence in the region, or if the specter of Cold War interventionist policies remained. Our sample included 455 responses from people working in US-based think tanks as well as policymakers from within the U.S. government. Our sample consisted of people working under the W. Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations, which captures a great deal of ideological variety.

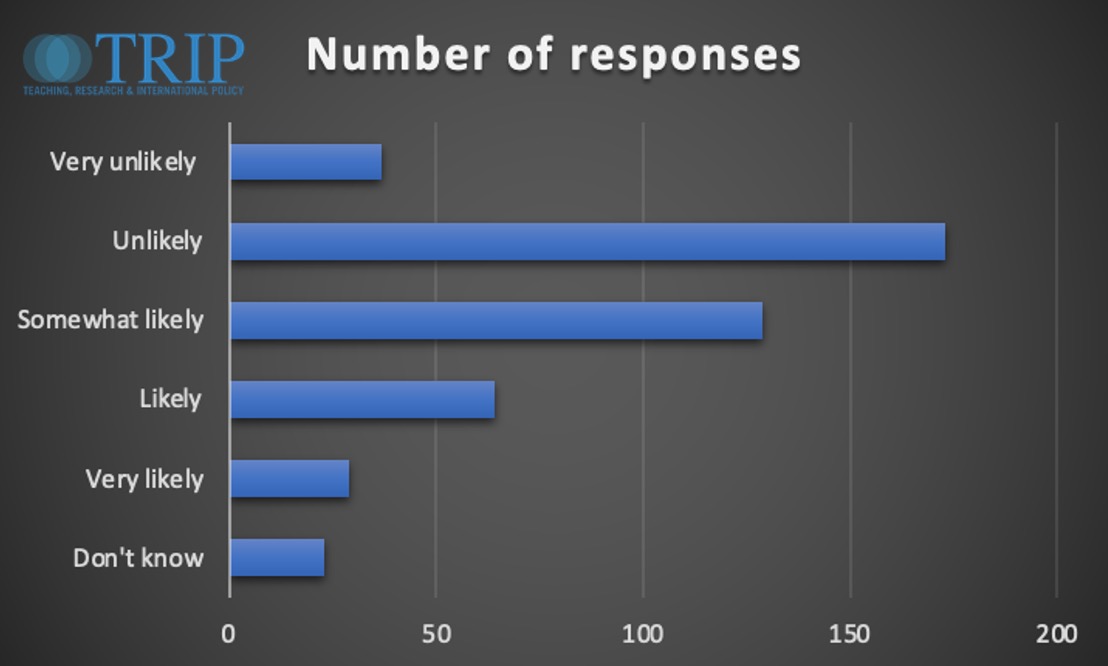

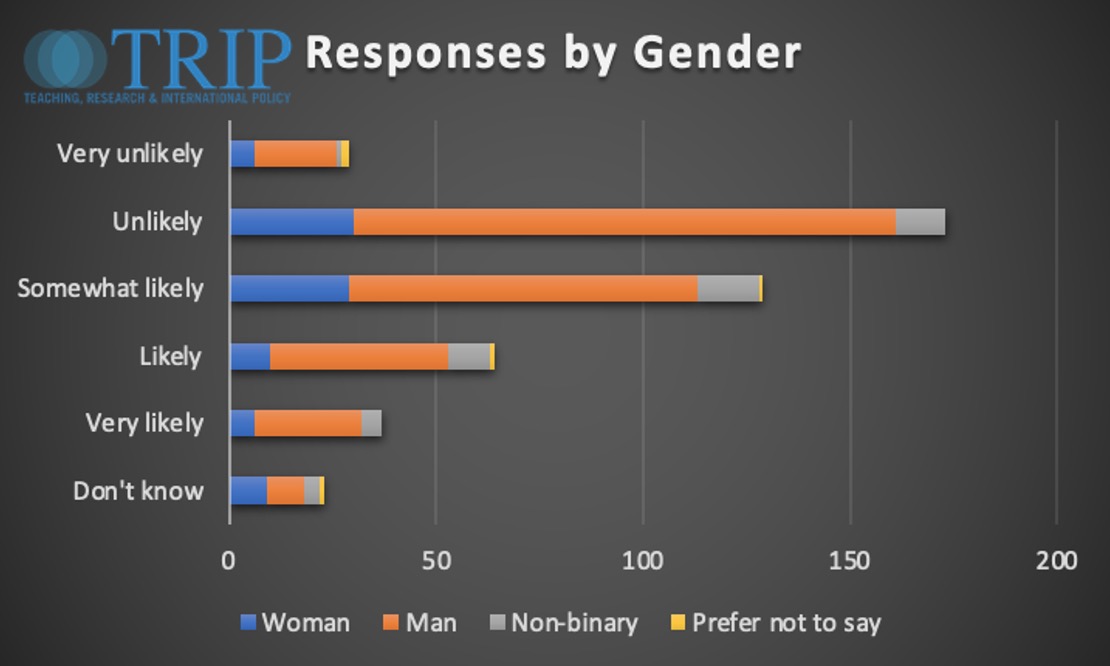

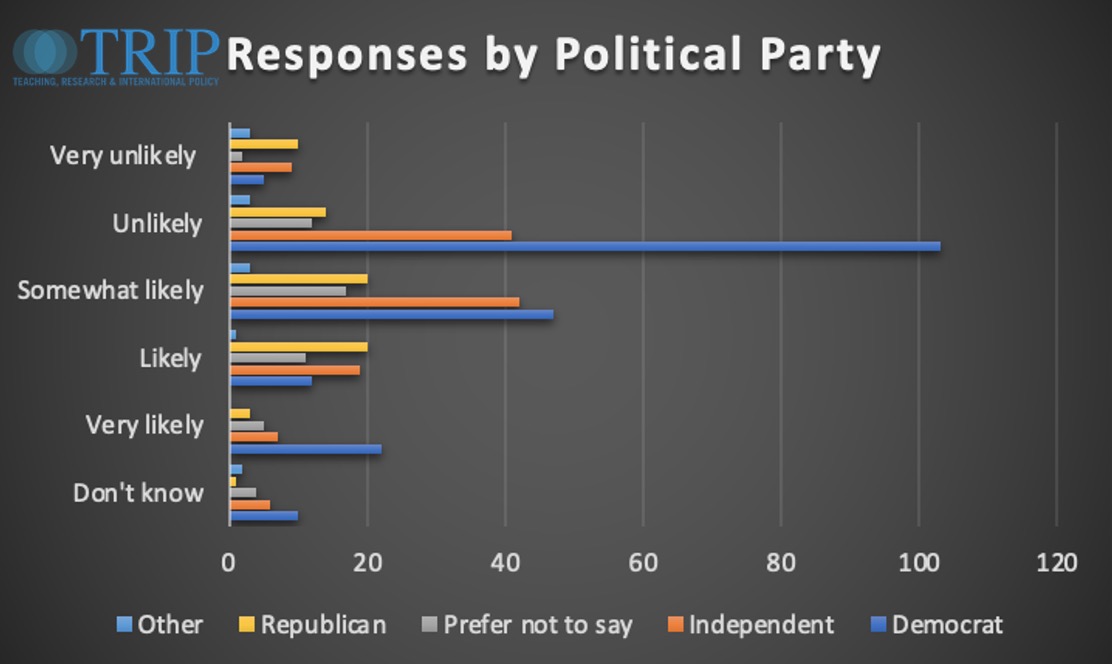

Based on our results, most respondents indicated that the likelihood of the wave of left-wing administrations recently elected in Latin America could be a threat to U.S. strategic interests in the region is overall, unlikely (see Figure 1, below). We also conducted basic cross analysis based on specific criteria to see if there were any trends. In this analysis, we focused on demographic factors such as age, ideology, ethnicity, political party (democrat, independent, republican or other), level of education, and gender (see Figure 2 and Figure 3, below). Our findings show that the majority of respondents who work in U.S. policy today or worked in US policy during the last three presidential administrations, consider it unlikely that the rise in left-wing administrations in Latin America would negatively affect U.S. foreign policy interests, even when we took into account different demographic information. Interestingly, political party affiliation did not significantly factor into people’s responses. These findings offer an interesting juxtaposition to the public positions of some US senators and representatives, suggesting that there may be an ideological divide between the technocratic and bureaucratic class of US policy makers and elected officials.

Pontifications from Congress

In preparations for the 2024 House bill, U.S. Representative Mario-Diaz Balart from Florida’s 26th district has advocated for deferring U.S. aid to Colombia. Representative Diaz-Balart has been publicly unhappy with the peace negotiations that have occurred between leftist Colombian President Gustavo Petro and the guerrilla group National Liberation Army (ELN). He claims that the House Appropriations Committee, of which he is of the State and Foreign Operations (SFOPS) Appropriations Subcommittee, will continue to “assess the actions of the Petro Government and its relations with Venezuela, Cuba and Russia, as the process moves forward.” The funding that would be deferred from Colombia would in turn be used to increase border enforcement and migrant processing, detention, and repatriation. This new spending legislation would enforce a 50 percent withholding of aid from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras until they affirm their support and cooperation in repatriation efforts for immigrants and countering drug and smuggling activity. However, the bill does not specify any sort of metric until funds are released once again.

We can also look to Texas Senator Ted Cruz, who has expressed disappointment in the fact that the Biden administration has not enforced disciplinary sanctions that in his eyes, threaten national security. He has criticized the Biden administration for welcoming the president of Brazil, President Lula da Silva, to the White House. He said, “Lula is an anti-American chavista who embraces the Chinese Communist Party, Vladimir Putin and the Iranian regime.” He justified this comment by recalling that in February 2023, Brazil allowed Iranian warships into their port in Rio de Janeiro and had not been sanctioned by the US in response. Cruz also brought up Biden’s lack of response against the former vice president of Argentina, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner. She was found guilty of abusing her public office and embezzling money via government contracts. Kirchener was sentenced to 6 years in prison and banned from office indefinitely. Cruz claims that she might have immunity in Argentina but it should not stop the US from imposing sanctions on her.

During the first Republican debate this month, candidates like Vivek Ramaswamy and Ron DeSantis expressed concerns over what is happening in Latin America, particularly surrounding the rise of China’s influence in the region. Supposedly out of concern for this hegemonic shift in the region, they said that they would revive the Monroe Doctrine, by which they will have the right to intervene in sovereign Latin American countries.

A Tale of Two Approaches Toward U.S. Foreign Policy in Latin America

As we’ve discussed, there is still a strong discourse coming from certain members of the U.S. Congress to push back on Latin American nations because they have leftist connections or administrations. These efforts mainly include financial aid retractions and sanctions. In contrast, our survey demonstrates that the bureaucratic and technocratic class working in U.S. foreign policy does not seem to be particularly concerned over ideological shifts to the left in the region.

The U.S. is reaching a point where it can take one of two approaches. The first approach would entail a return to an aggressive, interventionist approach, with a mentality that Latin America is the U.S. backyard, and the U.S. can infringe on the sovereignty of its neighbors with impunity. Former President Trump recalled this approach during the 73rd session of the United Nations General Assembly, where he expressed his desire to adopt the Monroe Doctrine, warning other nations not to intervene in U.S. business in Latin America. This approach has been echoed by other Republican Congresspersons.

The second approach would be a more mitigated one that the Biden administration has opted to take. They have welcomed many of these Latin American nations to the White House to talk about partnerships and alliances working towards common goals. These meetings have included Mexican President López Obrador, Argentine President Alberto Fernández, and Brazilian President Lula. However, the Biden administration still has a tendency to scold, as opposed to providing viable carrots to its southern neighbors. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers warned that the U.S. may be getting lonely in the region as China offers itself as a new, attractive partner to Latin American countries. He stated earlier this year, “Someone in a developing country told me that what we get from China is an airport. What we get from the United States is a lecture.”

If the U.S. wants to continue to enjoy its influence in the region, some members of the U.S. Congress may do well to take their cues from the practical attitudes of their bureaucratic governments in the region. Progressive governments in the region will likely not threaten U.S. interests in Latin America. But poor foreign policy decisions on the part of the U.S. toward their neighbors may do just that.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion — US Policies towards Latin America: What to Expect from the November Elections

- Monroe Reinterpreted: Trump 2.0’s Contemporary Approach to Latin America

- Unaccompanied Children on the Move: From Central America to the US via Mexico

- Opinion – Bolsonaro’s Foreign Policy is Typically Latin American

- The Killers’ Kindness: Gang Humanitarianism in Latin America

- China-Latin America Cooperation: An Alternative for Autonomy and Development?