The opening-up of China (or domestically as 改革開放 gai ge kai fang—reforms and opening-up) refers to a series of economic changes implemented in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) during the latter part of the 20th century, which are often described as “socialism with Chinese characteristics” and “socialist market economy”. Prior to 1978, the Chinese economy under Chairman Mao Zedong maintained centrally planned, state-controlled, and enclosed from foreign investments. After the death of Mao, Deng Xiaoping guided reforms within the ruling Communist Party of China (CPC) on December 18, 1978, during the “Buoluan Fanzheng” (撥亂反正—eliminate chaos and rectify the state) period. These reforms led to significant economic growth in China within the following decades. China surpassed Japan in 2010 to become the world’s second-largest economy in terms of nominal GDP, and then in 2017 it overtook the United States to become the world’s largest economy by GDP, as measured by PPP (Purchasing Power Parity). The exponential growth is often termed the “Chinese miracle”.[1] What is unique is that whilst other economically developed countries, such as the US and Japan, are ruled by liberal democratic governments, China has been ruled under a one-party authoritarian system, which is generally not associated with robust economies. Despite claiming that it is democratic, China’s economic development in the absence of political liberalisation is an intriguing case in the international arena. China has undoubtedly taken a turn to open up towards the West, and the rest of the world, by integrating its economy into the global market. Whilst the economic integration could have potentially allowed for further political liberalisations, it did not happen in China’s case. What complexities in China’s political culture, history, and economic reform stages prevented it from embracing liberal democratisation like other third-wave countries, and how did the CCP use nationalism as a defence mechanism against political liberalisation? With China and the Soviet Union both initiating reforms in the 1980s, what factors led to China’s success and the USSR’s collapse, and what implications does China’s experience have for international relations and politics?

The first part of the dissertation explores two factors: China’s political culture and its economic evolution. Under the culture factor, Confucianism, legalism, bureaucratic authoritarianism, nationalism and patriotism, and the role of the CCP will be examined. Under the economic evolution factor, the ideological foundation of the political and economic reform will be assessed prior to analysing the stages of economic reform. The second part of the dissertation explores the different trajectories of the Soviet Union and China, before assessing the potential applicability of the “China model”.

Current Narratives of the Correlation Between Economic Growth and Democratisation

Many narratives seek to explain the correlation between development and liberal democratisation. This dissertation will address two major bodies of literature: orthodox scholars who support the positive correlation between development and liberal democratisation, and scholars who challenge the correlation while exploring its nuances.

The orthodox perspective is discussed through the works of Lipset (1959) and Moore (1966), who establish the correlation between economic development and the rise of Western-style democracy. Fukuyama (1992) also contributes by asserting that human history has come to an end as “American” democracy is the most “evolved” form of government.[2] Lipset draws heavily on Marx and emphasises the role of the middle class. For him, the spread of education, the emphasis on political freedom, the pluralising interests and social ties, and the reduced intensity of redistribution conflict, make developed countries more amenable to liberal democracy.[3][4][5] Moore claims that “no bourgeois, no democracy”.[6] He highlights the importance of the balance of power, commercial agriculture, and the prevention of aristocratic-bourgeois coalition. Lipset and Moore argue that development increases the relative preferences of citizens or elites (or both) for democracy over dictatorship, improving the likelihood of a liberal democratic government.[7] Drawing on Hegel, Marx, and Nietzsche, Fukuyama contends that post-Cold War communism’s decline signifies the “end of history” and that liberal democracy is superior (ethically, politically, economically) to other systems. He also claims that all countries will eventually adopt liberal democracy.

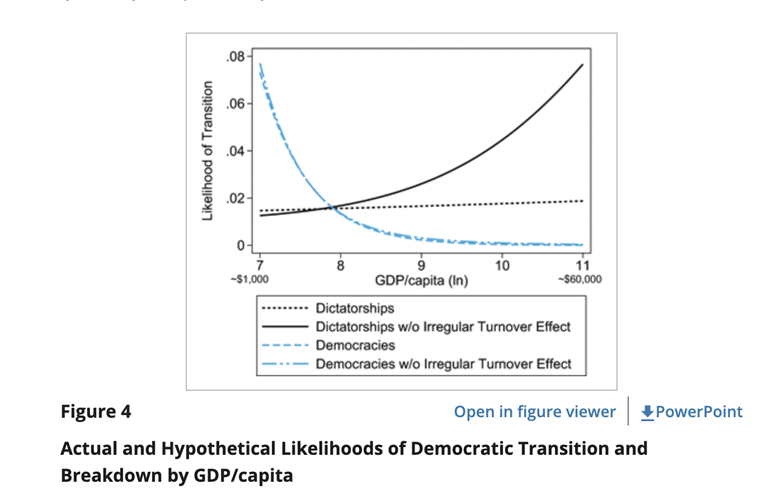

Contemporaries of the orthodox perspective do not necessarily dispute the above claims, but argue that the correlation follows without a causal effect. Przeworski et al. (2000) argue that democracies become “immortal” at high levels of income, but that income does not increase the probabilities of democratic transition after a certain point.[8] They also correlate human capital (measured by the level of education) with liberal democracy, stating that highly uneducated populations in non-democratic countries are unlikely to transition to liberal democracy.[9] Acemoglu et al. (2008, 2009) argue that development and democracy bear no causal relationship to each other, but are mutually caused by institutional history.[10] Whitehead et al. (1986) maintain that democratisation is likely to follow from a confluence of two factors: pro-democratic citizens and a vulnerable autocratic regime.[11] As Kennedy (2010) argues, “for an actor to push for democratisation, they must have the opportunity and means to overturn the current institutions and must also have the motive to support a democratic outcome”.[12] It can therefore be deduced that by strengthening regimes, development makes unstable periods less likely.

Carothers (2002) challenges the “old” transition paradigm, dismissing the importance of traditional democratic institutions, such as elections, and argues that democratisation does not necessarily unfold in stages.[13] His case studies of Taiwan, South Korea, and Mexico emphasise the importance of scrutinising reform sequences, as they show that democratisation does not always follow a standard process. Studying unique reform contexts can help understand the nuances of democratisation. Other scholars, such as Huntington (1991), German (2007), and Rustow (1970) agree that economic development reduces violent political instability in both democracies and dictatorships.[14] Democratic transitions in South Africa, Spain, Chile, etc, serve as examples of political violence disrupting the autocratic order and revealing regime weakness.[15] China’s relatively peaceful transition of power from Mao to Hua Guofeng did not generate enough stimulus for liberal democratisation. Even when faced with democratic opposition in 1989, the regime was strong enough to suppress it efficiently. External shocks, such as the defeat of war, can also stimulate democratic transitions, but China’s status as a great power makes it less vulnerable to democratic diffusion. Boix (2011) and Narizny (2012) indicate that the hierarchy of power in the international system conditions the causal effect of development on democracy.[16] Clients or former colonies of democratic hegemony are the countries most likely to democratise. As a great power that sees itself as the centre of East Asia, China is less likely to be impacted by the spill over effects of liberal democratic diffusion. Thus, even if there is a wave of democracy in Asia, China is unlikely to succumb to it.

Multiple authors have established the relationship between culture and liberal democratisation. Lipset and Huntington suggest that cultural factors appear to be more important than economic ones in democratisation, with Huntington considering “Confucian democracy” an oxymoron.[17][18] Liberal democracy, originating in Protestant Europe and North America, is better suited to Western cultures than non-Western ones. Confucianism and Islam are often seen as incompatible with democracy. Eastman links Taiwan’s disorganised political institutions to Chinese culture, characterised by authority-dependency, submissiveness, emphasis on personal relationships, and indifference to abstract principles, thereby illustrating its influence on administration, corruption, factionalism, and political repression.[19] Pye states that cultural factors “… fit together as a part of a meaningful whole and constitute an intelligible web of relations”. [20] He measures political culture by four themes: trust versus distrust, hierarchy versus equality, liberty versus coercion, and particularism versus universalism, and finds two competing and contradictory political cultures in China: orthodox Confucianism and a heterodox blend of Taoism, Buddhism, and regional beliefs. Despite their differences, both cultures view their highest leader – in China’s case, the General Secretary of the CCP – with great respect, and consider harmony a core value. The two competing cultures elucidate China’s shift from radical Maoism to pragmatic Dengism, and possibly Xi-ism. The 1989 Tiananmen protests further confirmed Pye’s belief in the influence of Chinese culture, which includes “the sensitivity of authority to the matter of ‘face’, the need for authority to pretend to omnipotence, the legitimacy of bewailing grievances, the urge to monopolise virtue and to claim the high ground of morality, the drive to try to shame others, an obsession with revenge, the inability to compromise publicly, and so on and on”.[21] However, Pye’s work predates China’s economic reform, limiting his hindsight. Culture significantly impacts China’s political system, as exemplified by Confucianism’s influence warranting further exploration.

Confucianism

The Confucian doctrine is an important ideological foundation for the CCP’s political narrative. Confucianism faced two periods of prohibition, first in the 1860s and later during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), when its schools and writings were extensively destroyed. The revival of Confucianism occurred only after the Revolution. Xi Jinping in 2014 gave a speech on the anniversary of Confucius’ birth which highlighted passages on peace and how they remain in China’s basic international relations ideology.[22] The compatibility of Confucianism with liberal democracy is debated. Some view it as supporting “oriental despotism,” while others argue it has humanistic and democratic qualities. Confucian and liberal democratic values have both similarities and differences, particularly in their perspectives on human nature. Confucianism concurs with liberal democracy in that human beings are rational and educable, but disagrees on whether human nature is good or bad. Liberal democracy assumes humans’ selfishness causes conflict, while Confucianism highlights their positive aspects. These differences result in practical implications: liberal democracy necessitates constraints on rulers’ power, while Confucianism relies on enlightened rulers to guide society. The second difference is that modern liberal democracy is associated with individualism, whilst Confucianism places a premium on familism. The emphasis on family values does not necessarily conflict with liberal democracy, but Confucianism regards filial piety as the utmost virtue in society, and is therefore fundamentally anti-individualist. This has stunted the development of individualism in modern times. The third difference is that Confucianism accepts and beautifies hierarchy. Confucius advises people to let the prince be a prince, the minister a minister, the father a father, and the son a son, and his ideas, which are instilled in society through their inclusion in school curricula, contribute to the coherence in political goals between the population and the government.[23]

Confucianism also shares common values with liberal democracy. Confucius specifies that rulers should avoid four characteristics: cruelty, oppression, injury, and meanness. He suggests that people should be enriched and then instructed, and believes that the interests of rulers are closely related to those of the people, forming a mutually beneficial relationship.[24] He gives priority to people’s trust, over sufficient food and weapons. Both Confucianism and liberal democracy advocate active participation in politics. Unlike Christianity’s distinction between the emperor’s (secular) and God’s (spiritual) affairs, Confucianism considers serving the emperor a gentleman’s duty, emphasising civic virtue.[25] The difference between liberal democracy and despotism lies in both their purposes and methods. In socioeconomic terms, the Confucian doctrine has strong egalitarian tendencies, which explains the coupling of market economy with centralised political control in modern China. Confucius believed rulers should focus on wealth distribution, not size of territory or population, as equal distribution prevents poverty. The similarities between Confucianism and liberal democracy explain two phenomena in Chinese development: Firstly, the shift away from Maoism, despite the prevalent reverence for Mao himself. The authoritarian regime thrives with the incorporation of certain democratic values, increasing the state’s diplomatic and social flexibility. Secondly, the CCP selectively uses Confucianism to justify actions, disregarding its values when convenient. Some argue that Chinese leadership pursued economic reform to modernise the country and improve living standards, while others believe it was to maintain power through economic growth and social stability. Additionally, there is the opinion that reforms aimed to attract foreign technology and capital, particularly from advanced countries like the US, to facilitate exports and drive rapid growth. It is likely that the leadership considered all these factors in pursuing economic reform, as each contributed to China’s development and global standing.[26][27][28][29]

Given the importance of Confucianism in modern Chinese politics, one might question the compatibility of archaic philosophy with unconventional socialism. Confucianism has not had a linear influence on Chinese politics. Confucius was influential between 800 to 200 BCE, and was regarded by Jaspers (1953) as a “paradigmatic personality”.[30] The doctrine’s influence was strengthened after the decision in 140 BCE by Emperor Wu (the sixth ruler of the Han dynasty) to turn Confucianism into a state ideology. Confucianism’s decline began with the 1911 Revolution, which terminated China’s monarchy, but it was further weakened during the Cultural Revolution.[31] Therefore, the resurgence of Confucianism was not only a backlash to the ideology behind the Communist ascent to power in 1949 but also a strong reaction to the philosophy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919, which declared that China must search for “science and democracy” and emancipate itself from the bondage of traditionalism.

Modern Confucianism, embraced by the CPC, highlights the strengths of the Chinese political system and supports the government’s political agenda. Bell contends that Western liberal democracy, based on the “one man, one vote” principle, has four key flaws: tyranny of the majority, of the economic minority, of the voting system at the cost of the non-voters, and of competitive individualists over those who favour a harmonious way of resolving social conflicts.[32][33] If the main objective of politics is to select capable leaders who can serve the common good, then the Chinese approach of political meritocracy, which involves extensive training and examinations for leaders throughout their careers, may offer valuable lessons for the West. The task for Chinese politics lies in harmonising the most effective aspects of meritocratic and liberal-democratic practices, since some level of electoral democracy is essential in a time when democratic elections are considered a standard for political legitimacy. In 2004, the concept of a “harmonious society” was formally announced by President Hu Jintao as a socioeconomic vision. Social harmony, a central Confucian value, contrasts with the Communist principle of class struggle, leading to suspicions that the CPC’s Confucian resurgence indicates a shift towards Confucianism. Since Xi’s rise to power, the Chinese government’s support for Confucianism has been remarkably robust. In his keynote speech in 2014, Xi stated that mankind nowadays faces many serious problems, such as “widening wealth gaps, endless greed for materialistic satisfaction and luxury, unrestrained extreme individualism, the continuous decline of social credit, and increasing tension between men and nature”.[34] He contends that Confucianism offers valuable insights to address these challenges.

As Chinese people experience growing material wealth, leading to increased greed, there is a need for spiritual realignment. Confucianism offers useful insights for “changing the situation, handling state affairs, and improving the morality of society”.[35] Nonetheless, it would be simplistic to not consider other intentions behind embracing Confucian principles. The CCP is not known for exhibiting kindness towards political dissent. The mechanism of selecting public servants overwhelmingly focuses on the candidates’ political ideology and loyalty to the party rather than the virtue and knowledge of Confucian classics.[36] Confucianism is helpful to the Communist regime in terms of consolidating its authoritarian control and resolving social problems. The current narrative of the Confucian doctrine adopted by the CPC has, to some extent, lost its original moral power. A new ideology blending Marxism-Leninism and Confucianism is emerging, promoted under the name of “socialism with Chinese characteristics”. The reintroduction of Confucian ideas may help the CPC find a local language more appealing to the people than Marxism, heighten the government’s sensitivity to social harmony and benevolent rule, and increase peaceful diplomatic interactions.

Legalism and Bureaucratic Authoritarianism

Another philosophical influence on Chinese politics is Legalism (法家 Fajia). Legalists believe that the rule of law is an instrument at the discretion of the ruler to consolidate their power, rather than a mechanism at the command of the people to control the ruler.[37] This is different from liberal democratic regimes, in which the rule of law constrains citizens as well as rulers. This doctrine undermines the liberal conception of representative government. Legalist laws give priority to duty and punishment, rather than rights and rewards. The goal of the state is to be wealthy in peacetime and powerful in chaos. In order to fulfil this, rights such as freedom of speech must be sacrificed, because freedom and diversity in words and deeds create chaos.[38] Legalism despises people and distrusts their judgment. It opposes social welfare: “the lazy and extravagant grow poor; the diligent and frugal get rich…”.[39] China’s historical authoritarian traditions contribute to the persistence of its authoritarian legacies. Chinese history is characterised by the so-called “dynastic cycle”. One of the controversial dictums in The Book of Lord Shang (475-221 BCE), a foundational book of Chinese legalism, states that “when people are weak, the state is strong; hence the state that possesses the Way devotes itself to weakening the people”[40][41][42][43]. There are many similar writings explaining Shang’s image as a “people-basher”, as the people’s intrinsic selfishness threatens social order, requiring a ruler to enforce laws and maintain control. The system of mandatory registration of the population and mutual responsibility groups help crime denunciation. Though Shang is known as an oppression advocate, his true perspective on the people is more nuanced. The Book of Lord Shang emphasises caring for people, viewing them as the ruler’s main asset. Legalism promotes a mix of incentives and punishments for obedience, with effective governance depending on a well-staffed, closely monitored bureaucracy. Legalists made lasting contributions to China’s administrative practices, believing that stability, in either the individual state or “All-under-Heaven”, requires an omnipotent monarch. The ruler is the only person who represents the common interests of the polity; as such, his power is conceived not as the means of personal enjoyment but as the common interests of his subjects. Thus, legalist rule is more sustainable than despotism because the ruler is considered a servant of humankind. A sole ruler is crucial as their unique authority can resolve disputes among ministers and maintain the hierarchical structure within the state, preventing potential collapse. The historical application of legalist theories significantly influenced the CCP’s discord with democratic principles.

Modern Authoritarianism and Neo-authoritarianism

China’s system has transformed into a sustainable and modernised authoritarianism, which is not only Marxist, but Marxist-Leninist. A Marxist system is primarily concerned with economic outcomes, whereas Leninism is a political doctrine with a primary aim of control. Thus, a Marxist-Leninist system concerns and balances both economic outcomes and maintaining control over the public and the system. The Leninist approach to leadership selection, used by the CCP, emphasises legitimacy through a bottom-up progression. Leaders start by managing a town, then a province, before serving in the Politburo, gaining familiarity with the country’s politics at various levels.[44] China’s Leninist governance model is argued to reduce arbitrary and nepotistic politics.[45] This unique authoritarian system establishes a social contract, as seen in Rongcheng, where big data and surveillance inform “social credit scores” that reward or penalise citizens based on political and financial behaviour, limiting access to certain activities such as purchasing an aeroplane ticket. This contract establishes a hierarchy that maintains control and equality. Whilst Liberals may see this as intrusive, it instils a sense of security in the population. The Three Gorges Dam is a prime example of a massive-scale project that could only be efficiently executed in an authoritarian country. The dam prevents flooding and provides 18,200 MW of hydroelectric capacity but costs US$25 billion and requires relocating 1.3 million people. Compared to projects such as the Big Dig in Boston and the Euro Tunnel, which took several decades to complete and encountered political opposition, the Three Gorges Dam was completed within a decade.[46] The streamlined decision-making process exclusive to authoritarian systems has efficiently marshalled scarce resources. The economic success and social benefits of these two examples explain the lack of popular demand for liberal democracy.

Conversely, some scholars argue that authoritarianism is not the key to China’s economic success.[47] Yang argues that China’s economic success is primarily attributed to the three decades of market reform, and that if government interventions were key to growth, China would have thrived more than three decades ago. Instead, it is the government’s “disinterestedness” towards society that allowed for a neutral stance regarding the divisions and unrest. This includes the Greater Chinese Democratic Jasmine Revolution, which came and went, and the party-state remained venerated.[48] The government is able to allocate resources according to the productive capacities of different groups, catalysing economic development. A disinterested government could appear in both authoritarian and democratic states, as long as the right social conditions and political arrangements are in place. However, one could argue that China’s apparent “disinterest” masks an inherently rigid political stance. Nevertheless, China’s lack of political liberalisation is simply because democracy is not necessary for economic growth. The Chinese government has attempted to strike a balance between economic growth and traditional values including Confucianism and Legalism, cultivating a complementary approach to governing. Viewing China’s government without considering the intricacies of its authoritarianism could be a serious oversimplification.

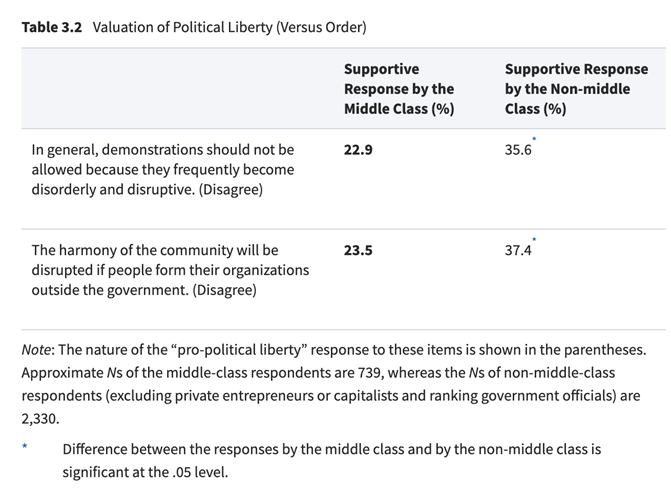

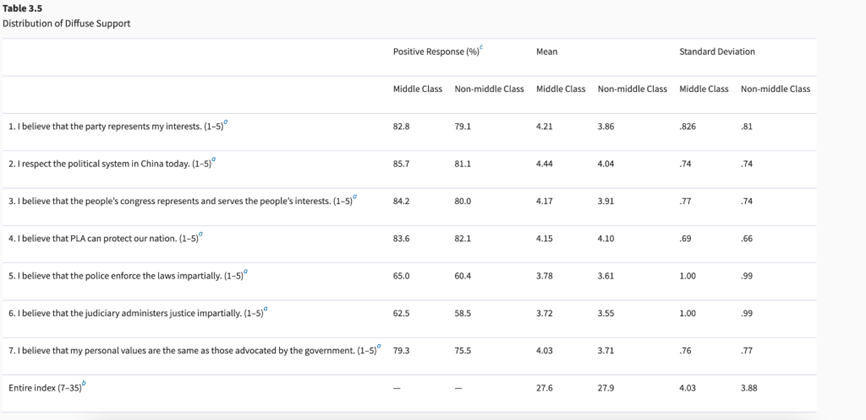

China’s modern authoritarianism has concurrently fostered a burgeoning middle class, which plays a pivotal role in upholding the regime’s legitimacy. A key difference between modern European and 21st-century Chinese middle class is their perception of Western-liberal-democratic models; Europeans embrace them as a basis for prosperity, while the Chinese may view them as threats to national security and stability. European middle classes typically demand political representation and civil liberties, while the Chinese middle class may prioritise economic stability and social order. This is in part due to the influence of Confucian and Legalist cultural values, which prioritise economic growth and stability over political liberalisation. Meanwhile, Confucianism’s focus on social hierarchy and respect for authority fosters a preference for robust leadership and a structured political system. This phenomenon challenges Moore’s idea that a strong middle class leads to liberal democracy, as the presence of landowners or state bureaucrats can inhibit an independent middle class and limit democratic prospects. Chen’s research (2013) reveals limited support for political freedom among China’s middle class, with only 23% supporting public demonstrations and 24% endorsing citizen-formed organisations, while non-middle-class respondents showed higher support for these ideas.[49][50][51] China lacks both a pro-democratic population and a vulnerable regime, which explains the middle class’s attitude towards liberal democratic values.[52] The Chinese middle class is essential for economic growth and the shift towards domestic consumption, and the government incorporates them by providing social and economic benefits while limiting political organisation.

Numerous scholars assert that China entered a phase of neo-authoritarianism.[53][54] Distinguished from traditional authoritarianism, neo-authoritarianism is not rooted in ideology, but focuses on pragmatic solutions addressing the challenges the Chinese government encounters while governing a vast, diverse, and rapidly evolving nation. By the late 1980s, many elements of Maoism had been abandoned in China, and a complete transition to capitalism seemed possible given past performance. Marxist scholar Hong Jian proposed that neo-authoritarianism requires a strong state and reform-minded elite, or “benevolent dictatorship”, to facilitate market reform and with it liberal democracy. Although China has maintained a long-standing dictatorship, neo-authoritarianism is perceived to pursue liberal democracy as a long-term objective by fostering markets, which are ultimately interdependent with democracy. The underlying assumption is that as markets become more open and interconnected, the need for transparency, accountability, and political freedoms will increase, ultimately driving a shift towards political liberalisation. Neoauthoritarianism diverges from both Maoism and Huntington’s narrative by asserting that economic change is a prerequisite for political change, whereas late Maoism views either one as capable of facilitating the other. The notion that superstructural development- including cultural, political, and ideological changes resulting from economic reforms and opening-up policies, was required for economic growth- appeared doubtful to Chinese leadership. Deng’s passing seemingly cleared the way for Jiang Zemin’s neo-authoritarian program. Despite market success and China’s perceived strength in adopting neo-authoritarianism and privatisation within a mixed economy, implementing radical policies risked negative consequences like unemployment, threatening the regime’s stability. The attempt at fostering a genuine neo-authoritarian environment was unsuccessful, as policies after Deng remained largely faithful to “market socialism”. In his 1994 article, Zheng elaborates that “administrative power should be strengthened in order to provide favourable conditions, especially stable politics, for market development”.[55] This indicates the mutually-dependent relationship between economic growth and political stability in China. Zheng maintains that political stability must be given the highest priority, otherwise, domestic construction would be impossible. Hence, an authoritarian regime is preferred in China when it ensures political stability.

Legitimacy, Nationalism, and Patriotism

Nationalism is instrumental in maintaining the Chinese regime’s legitimacy, which in turn prevents the rise of liberal democratisation. Following Mao’s death, the CCP shifted from relying on a cult of personality for popular support to basing its legitimacy on nationalism and economic prosperity as its twin pillars.[56] The legitimacy model posits that the security of the CCP depends on its capacity to enhance China’s economic conditions while safeguarding the nation’s interests. Historical and political factors, such as the Century of Humiliation, Japan’s imperialism and lack of reconciliation, and the US hostility towards China, are instrumental in supporting the legitimacy pillar. They also shape the nation’s collective identity and attitudes towards the outside world. Distinct from patriotism, which embodies love and loyalty for one’s nation, culture, and people, nationalism is a political term with a more robust ideological and collective significance. The emergence of Chinese nationalism (民族主義) can be traced back to the late Qing Dynasty when foreign influence and control led to what is usually perceived as China’s humiliation. Nationalism served as a unifying force against foreign interference. This raises the question of whether patriotism could have developed without foreign intervention, potentially grounded in Confucian ideals that emphasise loyalty to family, society, and the state. Deeply rooted in Chinese culture, filial piety expanded beyond loyalty to the state, encompassing community and heritage responsibility. To understand nationalism and patriotism in China, one should consider key historical and political influences:

Pre-1949 humiliation of China, also known as the Century of Humiliation

The Century of Humiliation refers to a period from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. During this time, China experienced a series of military defeats, forced concessions, and unequal treaties at the hands of foreign powers (such as the UK, US, and Germany). Despite recent successes, China’s deep-seated suspicions of Western intentions linger, intensifying disparities between China and Western nations. Hu Jintao warned in 2004 that “Western hostile forces have not yet given up the wild ambition of trying to subjugate us”.[57] This reinforced the CCP’s narrative of national rejuvenation under its leadership, further distancing China from the idea of embracing Western liberal democracy.

The end of the Qing Dynasty marked China’s decline from an empire to a semi-colonial country. Reformist Liang Qichao’s exile to Japan following failed attempts to reform the Qing government in 1896 highlights the rise of Chinese nationalism. World War I and the Treaty of Versailles, namely the demand for the concession of Shandong, further fueled nationalism, leading to the anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement in 1919. The Warlord Era saw the Kuomintang strengthen their national identity by reducing foreign influence.[58] Throughout the Chinese Civil War, Western interference persisted, and Mao’s reliance on Moscow’s support indicated that China was not completely independent from foreign influence. Consequently, nationalism as a self-defence mechanism can be understood as taking necessary steps, even if it involves external help, to protect the nation’s interests and identity in the face of perceived threats.

China’s approach to sovereignty since 1949 has been cautious, avoiding recognition of political separatism both domestically and globally. For instance, when Putin declared four regions as part of Russia in September, China maintained that those territories belonged to Ukraine, showcasing a shrewd diplomatic stance.[59][60][61] China’s history, marked by its imperial past, colonial struggles, and rising global influence, emphasises the importance of national unity, with ethnic minorities playing a vital role in maintaining cohesion and preventing separatism in frontier regions such as Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. China utilises sovereignty and independence as tools to counter separatist tendencies, aiming to preserve the unity of its civilisation against potential fragmentation driven by external forces.[62][63]

Japan’s Imperialism and Western Hostility

The numerous imposed agreements between China and foreign powers were collectively referred to as “unequal treaties,” which hindered China’s ability to attain power within the prevailing international order. An example of an unequal treaty is the 21 Demands, which was seen as a blatant infringement on China’s sovereignty.[64] By leveraging this treaty and its implications, the CCP promotes nationalism in China, emphasising the narrative of the nation as a victim of foreign aggression. This fueled a strong sense of national pride and a desire to overcome past humiliations, regain lost territories, and restore China’s rightful place in the world. In recent years, the CCP has demonstrated a reduced inclination to restrict the public expression of nationalism. Chinese nationalism includes diverse groups (e.g., the China Council for Promotion of Peaceful National Reunification), which collectively address concerns related to perceived affronts to Chinese integrity and identity. [65] Perceived offences include, but do not limit to, separatist ideas and movements initiated by ethnic minorities, and foreign intervention in Chinese geopolitical issues.

In March 2022, online calls emerged for boycotts of Nike and other fashion brands after they distanced themselves from Xinjiang cotton, a focal point of Western sanctions on human rights grounds. In July 2022, several individuals confronted Western journalists in Zhengzhou, alleging biased reporting following the month’s fatal floods that claimed hundreds of lives. Locals accused a German journalist of unfair allegations, originally made by BBC reporters, regarding the Chinese government’s lack of transparency and delayed rescue operations.[66] This demonstrates the effectiveness of the CCP’s attempts to stir nationalist emotions. The growth of Chinese nationalism can be attributed to the CCP’s efforts to strengthen its legitimacy, and the rising ambitions of China’s global standing as its influence expands.

Recent years have seen an increase anti-US and anti-Japanese sentiments, evident foreign policies. The 2010 Diaoyu dispute began with a trawler collision, leading to Japan arresting the Chinese crew. China’s spokesperson Jiang initially responded mildly, but anti-Japanese protests led by nationalist organisations prompted naval deployments and diplomatic suspensions, showcasing hardline Chinese nationalism. This illustrates the impact of nationalists on China’s government and the incorporation of nationalism into policies. The strengthening of economic power correlates with increasing nationalist sentiments and hardline diplomatic stance.

CCP’s need to create legitimacy

Nationalism is crucial for the Chinese regime’s legitimacy and acts as a deterrent to liberal democratisation. The younger generations (such as Gen N and Gen Z), born amidst China’s growth and a government-cultivated nationalist environment, tend to be more patriotic. National pride is linked to economic development, with successful companies like Alibaba, Huawei, and ByteDance showcasing China’s capabilities on the world stage. A July 2020 poll by Harvard’s Ash Centre revealed that 95% of Chinese citizens expressed satisfaction with the Beijing government.[67] [68] The state-owned newspaper, People’s Daily, often praises the CCP for fostering economic success, and calls to protect national interests against foreign intervention. It goes as far as to praise specific economic policies such as the 13th Five Year Plan, which is credited with growing China’s digital economy by 16.6% from 2016-2020.[69]Despite occasional economic stagnation, the CCP’s nationalist campaign persists to ensure national obedience.

However, China’s tolerance towards the late 2022 A4 protests against strict COVID-19 restrictions challenges assumptions of its unwavering hardline stance. Despite censorship, the government adjusted quarantine rules, reflecting public demands. The interethnic solidarity is a notable feature of the A4 protests.[70] The main protests were sparked by a lethal fire in Urumqi, the capital of the predominantly Muslim region of Xinjiang. Some among the majority Han Chinese realised that the spread of systemic oppression of minorities is now falling upon themselves. Others expressed that what is allowed to happen to a small population of Chinese people today would eventually affect everyone. The interethnic feature challenges the conception of nationalism in China, because the Chinese term used to refer to nationalism (民族主義) translates literally to “the doctrine of ethnicity”.[71] Whereas the Western perception of nationalism aligns closely with the identification of one’s own nation, regardless of ethnicity, the Chinese version associates closely with ethnic origins. This means that nationalism is untranslatable, and explains the uniqueness of the role of nationalism in China’s political trajectory.

The Role of the Communist Government

The role of the CCP is crucial in shaping China’s cultural narrative, particularly amid opposition. Since 1978, Deng aimed to foster national pride and identity by blending traditional Chinese culture with innovative socialist concepts, generating a sense of continuity that resonated with numerous Chinese people. The CCP actively endorsed values such as hard work, thrift, and loyalty to the state in order to build a “Socialist Spiritual civilisation” that supplanted the earlier “bourgeois” and “feudal” values. Chinese politician Hu recognised that the West maintains a higher level of advancement in numerous areas compared to China (such as technological innovation and GDP per capita), increasing the likelihood of Chinese individuals gravitating towards Western ideology.[72] Therefore, he states that “we must rely mainly on Communist ideology to battle the erosive influence of bourgeois ideology.”[73][74] Furthermore, the CCP integrated cultural symbols into everyday life by placing greater emphasis on celebrations like Chinese New Year, and organising grand events such as the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

In terms of the internal governmental structure, Deng stressed the desirability of separating the functions of the party from those of the government. The overlapping system in place that emerged by the 1950s was a response to the fact that certain high-ranking government officials, who persisted after the Communist takeover, were not party members.[75] A Communist Party unit had been established in each major government sector to ensure party control. By the 1980s, however, virtually all government officials in important positions were party members, and party supervision was no longer necessary. This minimises internal conflicts within the government, and maximises the coherence of ideology.

When faced with opposing opinions, Deng “purged” any Politburo members whose ideas did not align with his own. He rejected the broader demands for freedom as advocated by intellectuals in Zhao Ziyang’s political report draft for the 13th Party Congress, stating that “the main goal of our reform is to guarantee the efficiency of the executive organs without too many other interferences… Do not yield to the feelings for democracy… Democracy is only a means [to an end].”[76] Hu Yaobang was blamed for the loosening of party controls that led to student democratic demonstrations in 1986, and was pushed aside by Deng. Intellectuals whom Hu had protected, including Fang Lizhi and Liu Binyan, were all expelled from the party. This demonstrates Deng’s resolute leadership and the strict discipline he created for the CCP.

After Hu’s death on April 15, 1989, many young Chinese assembled in Beijing and other cities to pay tribute to their lost hero and his advocated democratic principles. As protests escalated, Deng deemed troops necessary. Zhao, opposing martial law, was subsequently placed under house arrest. Deng acknowledged that political reform was needed, but was firm about maintaining the four cardinal principles: upholding the socialist path, supporting the people’s democratic dictatorship, maintaining the leadership of the Communist Party, and upholding Marxist-Leninist-Mao Zedong Thought. From the night of 3 June to the morning of 4 June, demonstrators in Tiananmen were shot and run over by armoured soldiers and vehicles. At least 478 were dead and 920 wounded.[77] Student leaders like Wang Dan were imprisoned and eventually exiled to the West. Raised without room for independent political movements, subsequent generations learned from their predecessors that confronting leadership directly was not worth the consequences.

As the public expressed more open opposition to the government, Deng focused on economic progress and education to restore party legitimacy. Patriotism was emphasised in the renewed political education. The CCP accentuated the history of humiliation by foreign imperialists, and used the same narrative in propaganda and diplomacy. The Propaganda Department skilfully publicised anti-Chinese statements by foreigners- such as opposition to Beijing hosting the 2000 Olympics- that caused many Chinese, even students, to feel outraged. By late 1991, patriotic education was systematically taught through textbooks, lectures, and media guides.[78] In response to the 2019 extradition bill protests in Hong Kong, the CCP enacted the National Security Law in the city, justifying it as a measure to protect against foreign “black hand” forces aiming to undermine China’s territorial sovereignty. This illustrates the consistency in the CCP’s uncompromising stance against both internal and external opposition.

Factor II—Economic Evolution

Ideological Foundation for Economic Reform

Thestages of reformsis a key reason why China has not democratised despite its salient economic growth. Chinese economic reforms consist of four phases: rectifying damages from the Cultural Revolution, the first wave of liberalisations, state-private sector convergence, and the second wave of liberalisation. Deng, often credited as the “General Architect”, made national economic development the highest priority and emphasised the need to achieve the “liberation of productive forces”. He established the ideological groundwork for economic reform policies, asserting that political ideology reform is essential for political reform and democratic development. He viewed the shift in ideas as the foundational basis for China’s entire reform endeavour, identifying “emancipating our minds” as the primary task, and stating that “our drive for the four modernizations will get nowhere unless rigid thinking is broken down and the minds of cadres and of the masses are completed emancipated”.[79] This policy emphasised pragmatism and experimentation in economic planning. This entailed not only a policy change but also a cultural revolution, encouraging Chinese citizens to think critically, question authority (albeit within limits that wouldn’t undermine legitimacy), and embrace new ideas, reflecting a top-down strategy for establishing the ideological basis for economic reforms. Deng “combined Soviet-style big push industrialisation with an opening up to the capitalist world”.[80] Under his leadership, China opened its first Special Economic Zone (SEZ) and launched major efforts to attract foreign direct investment.[81] In an effort to emulate the success of Singapore, Deng proposed the goals of “Four Modernisations” and the idea of “xiaokang” (小康 “moderately prosperous society”) during the initial stages of the reform between 1979 to 1984. Deng began this series of reforms in agriculture, a sector long mismanaged by the CCP. He addressed past famines and food shortages by decentralising agriculture and implementing the household responsibility system, dividing People’s commune lands into private plots. Individuals could control their land, provided they sold a contracted crop portion to the government, leading to a 25% production increase between 1975 and 1985.[82] This bottom-up approach set a precedent for the privatisation of other parts of the economy.

Economic Development Before Political Reform

Political liberalisation in China was secondary to economic development during the reform era. The state, responsible for facilitating socioeconomic progress, often faces a dilemma between development and liberal democracy.[83] Differing from Western Europe or North America, state authorities in China are mandated to generate capitalism and economic development. On the one hand, the state must establish legitimacy and order; on the other hand, it should promote growth from above. However, these two goals are often in conflict. Liberal democracy requires accommodating various demands, while effective development demands state intervention, causing a tension that is difficult to reconcile in China’s case. State domination, therefore, makes it difficult for political liberalisation. Liberal democratisation is thus more likely to be bestowed upon society by the political elite, rather than emerging organically from significant social forces. In other words, democratisation is not necessarily a bottom-up process driven by the demands of the masses, but can be a top-down process initiated by those in power. Whereas liberal democracies allow private businesses to thrive, authoritarian regimes provide efficient demands to a developing country like China prior to the 1970s. Therefore, challenging the assumption that political and economic reform usually happen simultaneously, liberal democratisation has not been a priority to China.

In December 1978, Deng introduced the Open Door Policy which he reopened to foreign businesses. Gallagher (2002) argues that the sequence of reforms in China is the main explanation for its transitory trajectory.[84] China’s initial stage of economic development largely depended on Foreign-Directed Investment (FDI), which prevented political liberalisation in three ways: firstly, the formation of a foreign-invested sector created a laboratory for reform, in particular a laboratory of capitalism. Successful FDI liberalisation facilitated the implementation of challenging and destabilising changes. This opened previously restricted sectors like retail, power generation, and port development to foreign investors.[85] FDI liberalisation was an example of China’s dual-track reform, in which the state and the market each controlled an economic mechanism, with little competition. The foreign-invested SEZs in the early 1990s introduced destabilising reforms of employment, social welfare, and enterprise management.[86] Many of these practices were incorporated into laws and regulations intended for the foreign sector, circumventing direct clashes with socialist norms. The foreign sectors and SEZs primarily drew young and inexperienced workers, who were frequently unaware of socialist labour practices. FDI liberalisation divided societal components most likely to be adversely affected by economic reforms, particularly the urban working class, while expanding the urbanised workforce through the employment of rural migrants. This strengthened the Chinese state while weakening the civil society, delaying demands of political liberalisation. The dual-track system balanced the incorporation of capitalism and socialist operations, creating competitive pressure that benefitted both the state and society.[87] Secondly, FDI introduced competitive pressure across ownership types, prompting strategic incentives for local officials and gradual decentralisation. Regions competed for FDI, market share, profits, and skilled labour, while workers also competed for jobs, resulting in fragmentation that lowered social resistance to reform and postponed calls for political change. The competition between regions, domestic firms, and foreign-invested firms for FDI infusion was what Yang described as “competitive liberalisation”.[88] Competition drove convergence between capitalist practices and foreign firms, encouraging state enterprises to adopt foreign business methods to retain capital, technology, and international prestige. This constructive rivalry accelerated economic growth, strengthened foreign, private, and state sectors, and maintained political stability by focusing attention on economic progress.

Thirdly, FDI sparked ideological reformulation of public versus private sector debates. FDI liberalisation and the competition that followed have led to a radical reformulation of one of the key debates of the Socialist transition: the role of public ownership in a marketising economy. The Chinese regime preserved its legitimacy by recasting the debate as a matter of industrial survival amid growing competition. Unlike the Soviet Union’s shift from socialism to democracy under Mikhail Gorbachev, China adopted a nationalist viewpoint, protecting its leadership from accusations of betraying socialism. The Chinese economic reform was only a part of the much larger scope of industrial change. Even though Chinese State Owned Enterprises (SOE) were failing, reform in foreign investment and rural township village enterprises were yielding results. Deng’s 1992 Southern Tour to Shenzhen targeted specific areas of failure and amended inefficiencies of the state sector. State sector reforms heightened the focus on public ownership, allowing the government to exercise significant control over key sectors of the economy.

The success of FDI liberalisation stood in stark contrast to the failure of SOE reform and the development of the private sector. Economic development instigated by FDI liberalisation was sufficient to delay the need for political liberalisation. This reform process tends to encourage further reform, avoiding “partial reform” that creates “winners” who could deter further reform in order to preserve their special position. In sum, China’s lack of liberal democratisation can be attributed to the sequence of reforms, and the separation between economic and political reform since the late 1970s.[89] Moreover, the CCP’s understanding of democracy- “People’s democracy” or “Socialist democracy”- prioritises collective decision-making and social equality. This conflicts with the liberal ideas of individual freedoms, competitive elections, and the protection of minority interests. The Chinese government pursued economic reforms without radically changing its authoritarian system, and utilised reform results to reinforce the legitimacy and necessity of the regime.

However, the sequence cannot fully explain the success of China’s economic reforms. It has been widely acknowledged by Western scholars that Beijing did not intentionally carry out reforms in sequence. Rather, it was experimental, and prioritised reforms in areas with the least resistance. Former president Jiang Zemin called the reform process “yushi jujin” (與時俱進, keeping pace with the times). This suggests that the success of this sequence was more contingent, and revolved around broad goals of development and maintenance of regime legitimacy. The first phase of the economic reform was relatively smooth because many people, including the cadres persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, endorsed policies that sought to undo its detrimental effects. However, in the subsequent phases, when economic and political situations became more unpredictable, Chinese leaders could no longer follow a planned sequence for reforms. Evidence suggests that the Chinese government has not always successfully imposed its vision upon society. During the first 15 years of the Reform era, many policies reflected a compromise between the liberal and conservative wings of the Communist Party. Although ideological disagreements have diminished as a result of purges, bureaucratic conflicts have continued to shape the adoption and implementation of policies. Many of China’s most successful policies were first adopted locally, not as centrally-approved experiments but as violations of central policy, and were only subsequently endorsed on a national scale.

“China is writing its own book now. The book represents a fusion of Chinese thinking with lessons learned from the failure of globalisation culture in other places. The rest of the world has begun to study this book.”[90]

Upon historical examination, the Soviet Union and China shared comparable reform trajectories, yet their respective outcomes diverged significantly, highlighting the complexity of political and economic transformations in these contexts. This section will first compare the trajectories of China and the Soviet Union, then explore whether China’s experience can be theorised into a developmental model.

The Soviet Union and China—the Difference in Success and Failure

Several factors, such as the size of state sectors, reform strategies, the entrenchment of central planning, and historical context, contribute to the differing outcomes of China and the Soviet Union’s reform. While the USSR dedicated its resources and efforts on competing with the US, China did not have an equivalent competitor during the reforms. The interplay between nationalism and the economy also contributes to the differing experiences. Moreover, the countries’ leaders at the time, Deng and Gorbachev, had different agendas, leading to divergent paths.

The Soviet Union tried to reform its entrenched communist system at the end of its existence, and faced challenges from rising nationalism in its satellite states. Until early 1989, the Soviet Union’s political change outpaced that of its Eastern Bloc allies, inspiring political reformers throughout the communist world. Examples include Poland’s free elections in June 1989 and Hungary’s move towards political pluralism.[91][92] These movements demonstrate people’s desire to reclaim their national identity and sovereignty from Soviet control. Pei and Huang postulate that China’s state socialism was less developed than that in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, allowing for greater reform flexibility.[93][94] Successful socialist reform requires prerequisites such as a predominantly homogenous ethnicity, like China’s 92.2% Han majority, for unity and cohesion. Treisman avers that the homogeneity in China rendered political decentralisation fruitful, whereas the same process turned out to be disastrous in the divided Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.[95] The ethnic diversity in the Soviet Union’s satellite states complicated efforts to foster nationalism and unite people under socialism.

Economic factors also played a critical role in shaping the divergent trajectories of China and the Soviet Union. Sachs and Woo contend that the large state sector in the Soviet Union hindered gradual reform, as heavily subsidised state firm employees resisted moving to more dynamic non-state sectors. In contrast, a small state sector, large rural population, and small yet heavy industry contributed to the success of reform in China.[96] Solnick argues that while decentralisation in the Soviet Union triggered a bank run by local agents to seize organisation assets and property rights, the central government in China was ready to defend its reputation and prevent any bank run.[97] This shows that the Chinese government was more centralised and thus more prepared for reform backlashes.

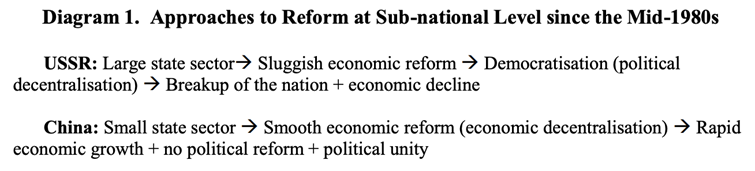

The Soviet Union’s predominant state sector hindered local reforms, prompting Gorbachev to seek democratisation for marketisation support. However, this further destabilised the economy. Perestroika faced strong opposition from conservatives, bureaucrats, and workers concerned about welfare losses, and Gorbachev’s emphasis on Glasnost and Demokratizatsiya resulted in political liberalisation and regional separatism. Economic instability contributed to the disorder. Moreover, the Soviet Union’s adversarial relationship with the US contrasted with China’s desire for global economic integration. Gorbachev faced immense external and domestic pressures, including the internal opposition by Boris Yeltsin. The USSR’s economic collapse resulted from not only shortages, unproductivity, and lack of innovation but also the massive allocation of resources to the arms race and experiencing imperial overstretch. Significantly, China did not have a superpower competitor during this time, which avoided having to spend much of its budget on defence purposes. In provinces like Guangdong, sizable non-state sectors facilitated the smooth initiation of market-oriented reforms. By 1978, non-state sectors accounted for 76% of China’s labour force, allowing for expansion and high growth.[98] This focus on expanding the non-state sector and allowing provinces the freedom to pursue their own reform course contributed to China’s continued growth. This economic success, achieved without democratisation, encouraged the CCP to maintain centralised power. Diagram 1 was adopted from Lai’s article to illustrate the different paths of the USSR and China.

Deng’s suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests reinforced authoritarian rule, which had set China on a trajectory towards a market economy without liberal democracy. Conversely, the Soviet Union adopted free speech and multiparty elections while experiencing severe economic depression, ultimately disintegrating into fifteen distinct nations.[99] Deng said during a meeting of top party leaders: “…only socialism can save China and turn it into a developed country” and “China’s greatest interest is stability— I never give an inch—ever.”[100] This prompts the question of whether political reform should precede economic reform or vice versa. During political turmoil, prioritising economic reform and stability may be essential as a nation’s foundation. Whilst the answer may not be certain, history has shown that China quickly recovered from the economic slowdown in 1990, whereas the Soviet economy continued to decline. Soviet liberals cited China as a reason to expand the private sector, while hardliners looked towards Tiananmen and emphasised political discipline and adherence to Leninist democratic centralism. This divergence diminished the popularity of Francis Fukuyama’s thesis, in which he suggested that liberal democracy no longer faced competitors for legitimacy.[101] China’s experience demonstrated that Marxism-Leninism, autocratic systems, or centrally planned economies do not inherently prevent a market transition, but does this Chinese case have practical or theoretical global implications?

Implications and Lessons from the “China model”

Some economists contend that China’s success highlights the advantages of a gradual, exploratory, and bottom-up strategy compared to the sweeping, top-down “shock therapy” approach that defined the transition in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.[102] Other economists argue that it is neither gradualism nor experimentation, but rather China’s unique conditions, i.e. large agricultural labour force, low subsidies to the population, and a decentralised economic system, that contributed to China’s success.[103] This suggests that China’s experience may not hold broader implications. The Chinese economy’s ability to grow despite institutional flaws can, in part, be attributed to its stage of development and fortunate circumstances.[104][105][106] However, China’s road to economic success was not as straightforward as the model suggests. The model neglects the prominent political and social factors that had a significant impact on the developmental path in China.

Although some argue that the Chinese experience is too distinctive to be duplicated in other contexts, there have been attempts made to generalise the “China model”. China has become a role model for Kazakhstan: a state with a dynamic economy that is comfortable with globalization trends and open to the world, whilst in control of its domestic politics.[107] Kazakhstan has implemented large-scale infrastructure projects, such as the construction of the Khorgos International Centre for Cross-Border Cooperation and the Astana International Financial Centre.[108] These projects are similar to the infrastructure investments in China that supported economic growth. Kazakhstan has focused on exporting its natural resources, such as oil, gas, and minerals, in a similar manner to China.[109] Kazakhstan has also sought to diversify its economy beyond the extractive industries and has looked to China as a model for developing its manufacturing and service sectors, as well as emphasising the role of the state in guiding economic development. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan recently followed the Kazakh example of looking toward China, rather than to Western-dominated international financial institutions, for new economic thinking.[110] However, the application of the “China model” in Kazakhstan is not without its challenges. For example, there have been concerns about the environmental impact of large-scale infrastructure projects and the impact of resource extraction on local communities. Nevertheless, this is sufficient to demonstrate that aspects of the “China model” can be adopted in developmental models, and potentially international relations theories.

Ramo labels what he sees as China’s unique economic approach as the “Beijing Consensus” (BC), distinguishing it from the “Washington Consensus” (WC). The BC is a useful touchstone to consider the evolution of developmental paradigms, compare China’s experience with that of others, identify the most distinctive features of China’s experience, and evaluate its significance and prospects for other countries. [111] Kennedy (2010), however, argues that the BC is not an accurate representation of China’s reform strategies. The BC is distinguished from the “China model”. The model, nevertheless, has its own caveats. The word “model” implies a coherence and guiding plan that likely does not square with the reality of China’s path. The economic reform has, in reality, proceeded through several stages, each different from the preceding one. In terms of politics, although China has adhered to a strict Communist, one-party rule, the Chinese leadership has initiated political reforms that were reactionary to social events. The experimentation aspect of the Chinese experience renders it more contingent, and less like a “model”. Nonetheless, China’s experience appears to give additional impetus to the breakdown of any universal dogma. It could provide an opening to reform for global governance institutions. Bell’s “three-tier model” succinctly summarizes the Chinese experience: “democracy at the bottom, experimentation in the middle, and meritocracy at the top”.[112]

Conclusion

To answer the questions posed in the introduction of this dissertation, the conventional model of development and democracy does not apply in China because of several reasons:[113][114] traditional cultural ideologies such as Confucianism and Legalism have laid a historical foundation for China’s political system, and the CCP strategically combined these ideas with Socialist values to foster nationalism and patriotism to maintain legitimacy. Confucianism and Legalism played a pivotal role in shaping China’s modern-authoritarian government by promoting a societal framework that values hierarchy and harmony over individualistic pursuits. Moreover, these two cultural foundations have been skillfully integrated into the CCP’s narrative to foster a nationalistic environment. This narrative consists of three interconnected parts: the “Century of Humiliation” is emphasised as a long-term historical factor that underscores China’s vulnerability to external powers; an ongoing perception of foreign hostility towards China is invoked to rally support and strengthen national unity; and the necessity of harnessing nationalism as a crucial tool for the CCP to maintain its legitimacy.

The economic evolution was also instrumental in China’s reform success and burgeoning one-party system. Liberal democracy was not vital for China’s growth, and the economic reform sequence further diverted the nation from liberal democratisation. In other words, China aimed to lift the nation out of dire conditions by prioritising economic growth and political stability over democratic liberalisation. China’s economic reform sequence avoided liberal democratisation by balancing capitalism and socialism through a dual-track system, fostering competition and decentralisation, and shifting the public-private debate to highlight industrial survival and nationalism, thus reinforcing regime legitimacy without radical political change.

The complex interplay of cultural and economic factors in China has constructed the current regime, characterised by economic liberalisation preceding political liberalisation and socialism with Chinese characteristics. The relative significance of cultural versus economic factors in restraining liberal democratisation in China remains uncertain, and it is recognised that these factors are contingent on China’s particular historical, social, and political circumstances. The influence of the cultural and economic factors is likely to continue to evolve as China develops and engages with the global community.

Despite having similar beginnings, the differing outcomes of China and the Soviet Union’s reforms were influenced by factors like state sector size, reform strategies, central planning entrenchment, and historical context. Ethnic homogeneity, economic factors, and external forces also played crucial roles. China’s experience showed that Marxism-Leninism and autocratic systems do not inherently prevent market transitions. Whilst the “China model” has influenced countries like Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, its generalisability is debated due to the country’s unique historical and political circumstances. Nonetheless, China’s reform and development experience has been exceptional in the international arena, defying textbook developmental models and offering valuable insights into international and political theories and practices. While it may be challenging to replicate China’s unique circumstances, the country’s pragmatic approach to reform can inspire alternative development strategies.

Figures and Tables

Source: Lai, 2005. Asian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 13, No. 1: p3. June 2005. Accessed 5 March 2023.

Source: Chen, Jie, ‘How Does the Middle Class View Democracy and the Chinese Communist Party Government?’, A Middle Class Without Democracy: Economic Growth and the Prospects for democratisation in China (2013; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 May 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199841639.003.0003 (Accessed 30 January, 2023)

Source: Chen, Jie, ‘How Does the Middle Class View Democracy and the Chinese Communist Party Government?’, A Middle Class Without Democracy: Economic Growth and the Prospects for democratisation in China (2013; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 May 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199841639.003.0003

Source: Miller, M.K. (2012), Economic Development, Violent Leader Removal, and democratisation. American Journal of Political Science, 56: 1002-1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00595.x.Accessed 26 November 2022.

References

[1]Ray, Alok. “The Chinese Economic Miracle: Lessons to Be Learnt.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 37, no. 37, 2002, pp. 3835–48. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4412606. Accessed 30 November 2022.

[2] Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. Penguin, 1992.

[3] Lipset, Seymour Martin. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” The American Political Science Review, vol. 53, no. 1, 1959, pp. 69–105. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1951731. Accessed 30 November 2022.

[4] Moore, Barrington. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. 1966.

[5]Miller, M.K., Economic Development, Violent Leader Removal, and democratisation. American Journal of Political Science, 2012. 56: 1002-1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00595.x Accessed 26 November 2022.

[6] Moore, Barrington. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. 1966.

[7] Miller, M.K., Economic Development, Violent Leader Removal, and democratisation. American Journal of Political Science, 2012. 56: 1002-1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00595.x Accessed 26 November 2022.

[8] Przeworski, Adam, et al. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

[9]Chin, J.J. The Longest March: Why China’s democratisation is Not Imminent. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 23, 63–82. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-017-9474-y Accessed 30 November 2023.

[10] Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, James A. Robinson, and Pierre Yared. “Income and Democracy.” American Economic Review, 2008. 98 (3): 808-42.

[11] Whitehead, Laurence, O’Donnell, Guillermo A.; Schmitter, Philippe C. Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Latin America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/book.72599.

[12] Kennedy, J. J. The price of democracy: Vote buying and village elections in China. Asian Politics & Policy. 2010. 2 (4), 617-631,

[13] Carothers, T. “The End of the Transition Paradigm”. Journal of Democracy, vol. 13, no. 1, Jan. 2002, pp. 5-21.

[14] Huntington, Samuel P.. Journal of Democracy, Volume 2, Number 2, Spring 1991, pp. 12-34 Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press. DOI: 10.1353/jod.1991.0016. Accessed 1 December 2022.

[15] In South Africa, the long struggle against apartheid and the subsequent transition to democracy was marked by significant civil violence and unrest. The African National Congress (ANC) led the struggle against apartheid, and its victory in the country’s first democratic elections in 1994 marked the end of white minority rule.

In Chile, The Pinochet regime in Chile was characterized by widespread human rights abuses and repression of political opposition. The opposition movement was initially divided and relatively weak, but the violent conflict between the government and armed leftist groups, such as the MIR and the FPMR, helped to galvanize popular support for democracy.

In Spain, activities such as terrorist attacks by the Basque Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) helped to mobilize a broad coalition of actors in support of democratic change.

[16] Boix, Carles. “Democracy, Development, and the International System.” American Political Science Review, vol. 105, no. 4, 2011, pp. 809–828., doi:10.1017/S0003055411000402. Accessed 2 December 2022.

[17] Lipset, Seymour Martin. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” The American Political Science Review, vol. 53, no. 1, 1959, pp. 69–105. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1951731. Accessed 30 November 2022.

[18] Huntington, Samuel P.. Journal of Democracy, Volume 2, Number 2, Spring 1991, pp. 12-34 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press. DOI: 10.1353/jod.1991.0016

[19] Eastman, L.E.. China’s Democratic Parties and the Temptations of Political Power, 1946-1947. In: Roads not Taken. [online] Routledge. 1992. ISBN9780429304910. Accessed 2 December 2022.

[20] Hu, Shaohua. Explaining Chinese democratisation. 2000.

[21] Pye, Lucian. The Spirit of Chinese Politics. 1968.

[22] Zhao, Quansheng. “The influence of Confucianism on Chinese politics and foreign policy.” Asian Education and Development Studies, vol. 7, no. 4, 2018, pp. 321-328. ProQuest, https://ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/influence-confucianism-on-chinese-politics/docview/2138506722/se-2, doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-03-2018-0057. Accessed 3 December 2022.

[23] Confucius. Confucian Analect. 12:11. 1901.

[24] Hu, Shaohua. Explaining Chinese democratisation. Pp23. 2000.

[25] Hu, Shaohua. Explaining Chinese democratisation. pp25. 2000.

[26] Nathan, Andrew J. China’s Transition. Columbia University Press, 1997.

[27] Pei, Minxin. China’s Capitalist Transformation. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

[28] Shirk, Susan L. The Political Logic of Economic Reform in China. University of California Press, 1993.

[29] Li, Cheng. China’s Political Development: Chinese and American Perspectives. Brookings Institution Press, 2014.

[30]Hu, Shaohua. Explaining Chinese democratisation. pp25. 2000. .

[31]Jiang, Y.-H.. Confucian Political Theory in Contemporary China. Annual Review of Political Science, 2018. 21(1), pp.155–173. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-020230. Accessed 4 December 2022.

[32]Bell, Daniel. The China model: political meritocracy and the limits of democracy. 2 June 2015. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400865505. OCLC 1032362345.

[33]Jiang, Y.-H. (2018). Confucian Political Theory in Contemporary China. Annual Review of Political Science, 21(1), pp.155–173. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-020230. Accessed 3 December 2022.

[34]Xi, Jinping. Speech at the opening meeting of the International Academic Symposium in Commemoration of the 2565th Anniversary of the Birth of Confucius and the Fifth General Assembly of the International Confucian Federation. September 24, 2014.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Even in Hong Kong’s civil service exam (BLNST), candidates are required to pass a knowledge test on the newly introduced National Security Law (2020).

[37] Hu, Shaohua. Explaining Chinese democratisation. pp29. 2000.

[38]Han, Fei, and Burton Watson. Han Fei Tzu : Basic Writings ; Transl. By Burton Watson. Columbia University Press, Cop, 1964.

[39] Ibid.

[40] The Book of Lord Shang is a Chinese classic written during the Warring States period (475-221 BCE), which was a time of intense warfare and political instability in ancient China. Lord Shang Yang, who served as a statesman and reformer in the state of Qin during this period, is traditionally credited as the author of the book.

[41] Pines, Yuri, “Legalism in Chinese Philosophy”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2018/entries/chinese-legalism/>. Accessed 3 December 2022.

[42] Shang jun shu 20: 121, 3rd century BC.

[43] Book of Lord Shang 20.1. 3rd century BC.

[44]Chen, Jie, ‘How Does the Middle Class View Democracy and the Chinese Communist Party Government?’, A Middle Class Without Democracy: Economic Growth and the Prospects for democratisation in China (2013; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 May 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199841639.003.0003. Accessed 4 December 2022.

[45] Ibid.

[46] “China’s Three Gorges Dam sets world hydropower production record – China Daily”. spglobal.com. January 3, 2021.

[47]Yang, Y. Authoritarianism not key to China’s economic success. [online] East Asia Forum. 2011. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2011/11/20/authoritarianism-not-key-to-china-s-economic-success/. Accessed 4 December 2022.

[48] Hung, H. Confucianism and political dissent in China. [online] East Asia Forum. 2011. Available at: https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2011/07/26/confucianism-and-political-dissent-in-china/. Accessed 4 December 2022.

[49]Chen, Jie, ‘How Does the Middle Class View Democracy and the Chinese Communist Party Government?’, A Middle Class Without Democracy: Economic Growth and the Prospects for democratisation in China (2013; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 May 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199841639.003.0003. Accessed 4 December 2022.

[50] Appendix A.

[51] Appendix B.

[52] Whitehead, Laurence, O’Donnell, Guillermo A.; Schmitter, Philippe C. Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Latin America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/book.72599.

[53] Yun, M. S. The Rise and Fall of Neo-Authoritarianism in China. China Information, 5(3), 1–18. 1990. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X9000500301. Accessed 26 November 2022.

[54] Sautman, Barry. “Sirens of the Strongman: Neo-Authoritarianism in Recent Chinese Political Theory.” The China Quarterly, no. 129, 1992, pp. 72–102. 1992. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/654598. Accessed 26 Apr. 2023.

[55] Zheng, Yongnian. “Development and Democracy: Are They Compatible in China?” Political Science Quarterly, vol. 109, no. 2, 1994, pp. 235–59. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2152624. Accessed 8 January 2023. Full quote: “administrative power should be strengthened in order to provide favourable conditions, especially stable politics, for market development. Without such a political instrument, both ‘reform’ and ‘open door’ are impossible…”

[56] Reilly, James. “CHINA’S HISTORY ACTIVISTS AND THE WAR OF RESISTANCE AGAINST JAPAN: History in the Making.” Asian Survey, vol. 44, no. 2, 2004, pp. 276–94. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2004.44.2.276. Accessed 26 March 2023.

[57] 胡锦涛 [Hu Jintao], “认清新世纪新阶段我军历史使命 [See Clearly Our Military’s Historic Missions in the New Century of the New Period],” December 24, 2004. <https://gfjy.jxnews.com.cn/system/2010/04/16/011353408.shtml>. Accessed 2 February 2023.

[58] 沈潔. 辛亥革命前后民族主义是如何深入民心的. 東方早報. (原始內容存檔於2020-12-01)Accessed 26 April 2023.

[59] On 30 September 2022, Russia, amid an ongoing invasion of Ukraine, unilaterally declared its annexation of areas in and around four Ukrainian oblasts – Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia.

[60] Pjotr Sauer and Luke Harding. “Putin Annexes Four Regions of Ukraine in Major Escalation of Russia’s War.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 30 Sept. 2022, www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/30/putin-russia-war-annexes-ukraine-regions#:~:text=Putin%20annexes%20four%20regions%20of%20Ukraine%20in%20major%20escalation%20of%20Russia’s%20war,-This%20article%20is&text=Vladimir%20Putin%20has%20signed%20%E2%80%9Caccession,since%20the%20second%20world%20war. Accessed 26 April 2023.

[61] Sheena Chestnut Greitens; China’s Response to War in Ukraine. Asian Survey 1 December 2022; 62 (5-6): 751–781. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2022.1807273. Accessed 26 April 2023.

[62] Brown, K. China’s world : what does China want? London: I.B. Tauris. 2017. Accessed 26 April 2023.