This case study is an excerpt from McGlinchey, Stephen. 2022. Foundations of International Relations (London: Bloomsbury).

Capital punishment is the practice of executing someone following a legal process, commonly known as the death penalty. Instances of using the death penalty are as old as recorded history, but in the modern era they have become more the exception rather than the rule as states favour imprisonment and rehabilitation. Those states that still use the death penalty typically reserve it for the most serious of crimes such as murder, terrorism, treason and sometimes also drug offences. Amnesty International’s annual report (2020) cited China as the state with the most executions that year, having executed ‘thousands’ of citizens. Iran is second on the list approximately 250 executions, and Saudi Arabia third with 184. These three states have maintained the top three positions in the global execution figures for several years. The figures are often approximate due to the secretive nature of certain regimes, especially China where death penalty records are state secrets.

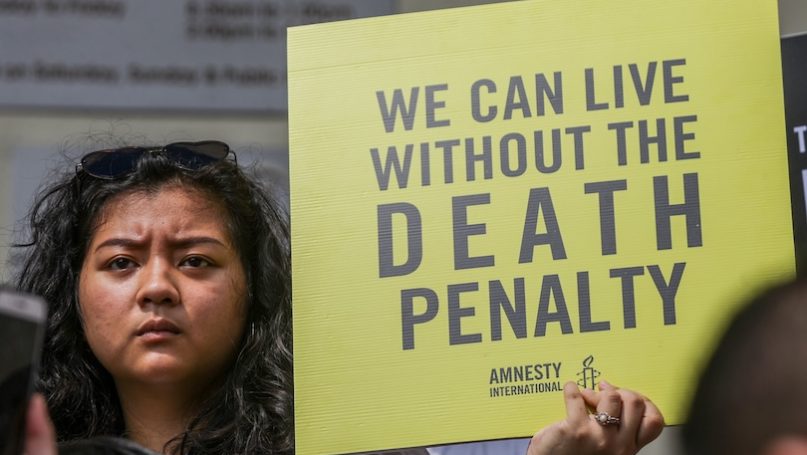

The goal of abolishing the death penalty is a key aspiration of human rights activism (see Hodgkinson and Schabas 2004). It is a contemporary example of how initiatives backed by civil society organisations can have lasting impact. This mobilisation was only possible because a number of ‘rival’ civil society organisations decided to work together. Despite the differences, these organisations managed to find a middle ground on an operative basis. While the topic of the death penalty has been debated for centuries, it is only in recent decades that significant institutional changes have occurred, with a number of states removing capital punishment from their legal systems.

The anti-death penalty stance only managed to gain importance at the United Nations level due to the specific transnational mobilisation of civil society organisations (Marchetti 2016). While earlier activism contributed to creating the right political context at the national level, it was the campaign for a moratorium on the death penalty that specifically targeted the United Nations. This ultimately led to a UN General Assembly resolution in 2007, that was reconfirmed several times in subsequent years, and today remains a significant human rights benchmark. The campaign not only contributed to having the United Nations pass a (non-binding) resolution with a global scope, but was also important in persuading a large number of states to abandon the death penalty.

In material terms, the campaign developed through a multi-stage process of normative promotion. It began in a specific place – Italy. It then became stronger by ‘going transnational’ via civil society organisations networking together and sharing resources and ideas. The campaign then returned to the national domains so that key target states could be persuaded to back it from within their own political systems. Finally, the campaign targeted the United Nations, where it successfully achieved the backing of the General Assembly. As for institutional strategies, between pressure (hard dynamics) or persuasion (soft socialisation), the main approach of this campaign consisted in lobbying local, national, European and global public institutions with soft persuasion initiatives. In terms of targets, the campaigning aimed principally at influencing public institutions and key actors within them. The selection of this specific strategy was dependent on the type of goal the campaign set for itself.

Affecting the very existence of citizens who risk execution (especially in cases where innocence is maintained, despite any legal rulings) the issue of the death penalty is by definition at the core of any legal system aimed at providing security to its members. Given such a nature, any change in its regulatory framework cannot avoid discourse and bargaining with the very public institutions that can carry out executions legally. As a consequence, this kind of activism intended to modify the legislative position within states and, in order to achieve that, it operated institutionally both at the national and international levels. While other kinds of initiatives aimed at the wider public were successfully developed and secured broader public support, public institutions who stood able to promote legal reforms were prioritised as targets. However, public institutions were not only targets, they also became partners. Most of the persuasive activities of the campaign were developed in synergy with public institutions which provided financial, political, or procedural support due to a growing normative acceptance across multiple societies that the death penalty should be abandoned.

Two communicative moves had a particular importance in the campaign strategy: framing and story-telling. Beyond the strategic decisions to develop a transnational coalition and to enact multi-layered lobbying, the specific tactical decisions that most characterised this campaign were very much based on the nuanced combination of reasons and emotions. On the one hand, the construction of a cosmopolitan frame mainly based on universal human rights, intended as a rational tool to challenge, from a legal point of view, the traditional understanding of the death penalty in terms of sovereignty. On the other hand, ‘humanitarian missions’ led by civil society organisations in swing countries, intended as an emotional tool to persuade institutional gate-keepers and veto players to change their position in favour of the moratorium.

The dynamics of the process cannot be fully captured without making clear the part played by tactics of persuasion. Humanitarian diplomacy developed by civil society organisations through persuasion activities remains key. In this case the undertaking featured two main components. First, the idea of the right to life was communicated persuasively as a desirable outcome – something that attached well to several already popular international agendas. Second, an empathic process was generated by using powerful narratives drawn from individual cases. These were mainly stories told by people previously sentenced to death and now pardoned, or moving accounts by their relatives. In both cases, civil society organisations played a central role as either reason-based frame creators or emotion-based narrative disseminators. They played an important role as an alternative and/or adjunct to diplomatic politics and achieved a clear and lasting impact at the international level that has ensured that the death penalty increasingly becomes the exception, rather than the rule.