Despite Tannenwald’s (1999) argument that “a normative prohibition on nuclear use has developed in the global system, which […] has stigmatized nuclear weapons as unacceptable weapons of mass destruction” (p. 433), nuclear proliferation continues to be an international security issue of global concern. To tackle this issue, states have concluded several international agreements, such as the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) of 1968, giving life to the nuclear non-proliferation (NNP) regime. The legal system devised by such treaties, as well as by a series of norms, has been praised for halting the development of global nuclear weapons despite the inequality that lies at the basis of this regime (Nye, 1985). In fact, the NNP order is rooted in a division between nuclear-weapon (NWS) and non-nuclear weapon states (NNWS), which not only renders complete nuclear disarmament laid out in Article VI of the NPT a utopia at best and perpetuates certain unequal dynamics in international law. These dynamics are further seen in how the nuclear programs of some states are condemned while others are tolerated.

Accordingly, this paper aims to study the relationship between imperialism and international law and how such a relationship generates a series of unequal mechanisms in nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation law. In particular, this research wishes to examine a specific type of discriminatory practice undertaken by the so-called “West” that targets certain countries within the group of NNWS. This practice assigns different levels of tolerance to the nuclear programs of countries that have not complied with the regime in place. The cases that will be analyzed will be Iran and India. Case selection will be discussed in the methodology section.

An awareness of the inequalities present in NNP law is necessary to re-think critically the difference in how states and non-compliant states, in particular, are treated in the international sphere. Such treatment calls into question the idea that not all states possess full sovereign equality, which is something opposite to what international law preaches in theory. This is significant because, by adhering to the common view on who is entitled to nuclear proliferation and who is not, the main discourse fails to recognize how such portrayal may fail to comprehensively understand nuclear issues individually and achieve complete nuclear disarmament globally. Therefore, the relevance of this research is related to the need to give a spin to the accepted view that supports the status quo of the current NNP legal order and examine how the prevailing and mostly Western representation of different non-compliant states may not only be partly distorting reality but could also be influencing the consideration of alternative approaches to the issue of nuclear weapons development.

The first part of the paper will introduce the chosen theoretical framework that will be based on contributions from legal scholars who address imperialism in international law and postcolonial theories. Afterwards, the article will discuss the methodology that will structure the study, which will include a series of methods that will be placed within Simpson’s (2004) understanding of how sovereign (in)equality is constructed in the international system. The main body will deal with the empirical analysis of Western political discourse on NNP. Lastly, the paper will conclude with a discussion of the results and consequences of sovereign (in)equality.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework includes a combination of contributions coming from authors who focus on the connection between imperialism and international law, as well as from postcolonial scholars. Starting with the first group, the link between imperialism and international law is analyzed through the work of authors such as Anghie (2005; 2006; 2012; 2014; 2016), Simpson (2004), Starski & Kämmerer (2017), Rasulov (2017), and Orford (2003; 2011), among others. The theoretical contributions of these authors (and many others who belong to the Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) scholarship) are considered because of their criticism of the de facto division of states into different categories and how such division dates back to the initial shaping of international law during the period of colonial expansion that had its climax in the nineteenth century. Their writings explore how such division generates a hierarchical structure in which sovereign equality is applied unequally throughout the international system, even after decolonization has taken place.

To understand these scholars’ contributions, we may examine one of its most important representatives, Antony Anghie. Anghie (2016) criticizes those who regard colonialism as a practical issue that is political in nature and positions imperialism at the center of international law. He looks particularly at the colonial origins of international law by analyzing the work of sixteenth-century Spanish jurist Francisco de Vitoria and observes how his writings envisioned a new global legal system that overthrew the framework devised by the Catholic Church, which ordered relations between Europe and “the Saracens to the Indies” (Anghie, 2012, p. 17). Vitoria is known for supplanting this framework based on divine law with one rooted in natural law; however, he still regarded the Spanish and the Indians as belonging to two different systems (Anghie, 2012, pp. 19-20).

Vitoria believed that the Indians were rational beings who were thus included in the system of jus gentium,meaning that they should have been able to trade equally with the Spanish and vice versa; nevertheless, their inclusion into such a system actually allowed the Spanish to enter the territories of the Indians indiscriminately, and the Indians could not impede them from doing so as this would be understood as a declaration of war (Anghie, 2012, pp. 21-22). With this in mind, Anghie (2005) argues that “what is […] illuminating about Vitoria’s arguments is his deployment of what we might term ‘humanitarian’ or ‘human rights’ arguments for imperial purposes” (p. 63). Furthermore, cultural differences between the two sides, and specifically the lack of adherence of the Indians to “universal norms”, also legitimized their subjugation by the Spanish (Anghie, 2012, pp. 21-22).

This construction of legal supremacy resonates across centuries by transforming itself while never vanishing. Within this context, a part of Anghie’s argument is particularly useful to frame this study. This would be the way in which the continuous influence of Western imperialism is seen in the present international legal framework in a division that often separates between and among states. According to Anghie (2005), in the present:

[T]he world may be divided into law-abiding states and ‘rogue states’, pre-modern and postmodern states, non-democratic and democratic states, and that only members belonging to the former categories […] are proper members of the international community and can therefore exercise certain fundamental rights. (p. 51)

Thus, this author argues that dichotomous distinctions are still employed by the West through discourse, in the same way that in the nineteenth century, Western countries separated civilized sovereign states that were considered part of the international community from uncivilized entities that were not only placed outside such community but could also not enjoy full sovereign rights (Anghie, 2005, p. 51).

Another important point made by Anghie (2016) is that the making of the distinction between states during the nineteenth century allowed the legitimization of a “civilizing mission” by the West directed towards uncivilized states, which in current times has been translated into the use of international law and its bodies to take the place that was once occupied by Western conquistadores and colonizers (p. 166). In this way, as explained by Rasulov (2017), throughout the centuries, the discriminatory categorization of states in the international system has been transformed but never given up (p. 19). The continuous renewal of imperialist discrimination directed towards certain countries has been based on a classification that Western narratives have shaped and made the norm to their own advantage, authorizing actions and language that would not have been tolerated if the target was those sovereign entities whose characteristics fully belong to the “family of nations”.

This point is also evident in Simpson’s (2004) work, which this paper also draws from, not just theoretically but also methodologically. As this author argues, the idea that the current legal order is founded on the legal equality of states is “incomplete” (Simpson, 2004, p. 6). In reality, the international legal system is made up of “unequal sovereigns” that are “differentiated in law according to their moral nature, material and intellectual power, ideological disposition or cultural attributes” (Simpson, 2004, p. 6). According to Simpson (2004), this disparity is seen mainly in two of the three spheres of sovereign equality, legislative and existential (formal is the third), which are undermined by two types of legalized hierarchies, legalized hegemony and (liberal) anti-pluralism (pp. 6-7). This last concept is primarily considered for the analysis undertaken in this article, as it will be seen in the section on methodology.

Now, what all the authors mentioned previously do in the legal field is explore the way in which power relations still exist in the present postcolonial era. This is precisely what postcolonial theories highlight as well. Accordingly, this study borrows from postcolonialism in its attempt to “pay particular attention to the — seemingly innocuous — guise in which elements of colonial discourse and structures have outlived the formal end of the colonial rule and continue to exert strong influence today in politics, culture, economics, art, science and law” (Dann & Hanschmann, 2012, p. 124). Specifically, paternalistic attitudes towards countries outside of the Western cultural radar are one of the ways in which colonialism continues to dictate the fate of many states in the international system (Orford, 2003).

A postcolonial approach is useful to observe not only how unequal sovereignty in NNP law can be found at the intersection between imperialism, international law, and the postcolonial space but also to acknowledge how such links have produced and re-produced the idea of “the Other”. Famous postcolonial authors such as Said (1978; 1994), Spivak (1988; 1999), Bhabha (1994), and Gregory (2004), among others, deliver through their writings some of the tools that allow us to break down how many of the perceptions of the present are still impregnated with an us-versus-them type of discourse, as it occurred during colonial times, further excluding certain states. The type of discourse revealed by these authors has changed but not disappeared. As a result, the West has often continued to dictate the rules of the game in the international system while shaping the perception of the “rule of law” and its application.

To better comprehend the inputs of postcolonial scholars into the theoretical framework selected, we need to consider the crucial contributions of Edward Said. Said (1978) explores the formulation of the idea of “the Orient” by the West, and he does so by accentuating that “the Orient is […] one of its deepest and most recurring images of the Other. […] the Orient has helped to define Europe (or the West) as its contrasting image, idea, personality, experience” (p. 26). Said indicates that it is in the division between what is other than Western that the West constructs its own idea of Self, and this division can not only be put to many different uses but also prove to be a practice at the mercy of the imperialist project. As also explained by Chowdhry & Nair (2002), “imperialism constitutes a critical historical juncture in which postcolonial national identities are constructed in opposition to European ones, and come to be understood as Europe’s ‘others’; the imperialist project thus shapes the postcolonial world and the West” (p. 2). This is further accomplished by considering the disjunction between these two realities as being a separation between that which is right, acceptable, civilized, and sovereign and that which, by its being different from the former, cannot be recognized as any of these things.

Several aspects are troubling in the shaping of this dichotomy. The first is that the re-production of opposite representations reinforces both sides of the equation, namely Western imperialist ventures on the one side and nationalism in the Global South on the other (Said, 1994, p. xxiv). This may create and deepen cleavages and conflicts. Another is exposed by Spivak (1988), who underlines how the constitution of the colonial subject excludes the voice of this subject in the definition of themselves, which translates into an account of reality that becomes the norm despite not representing the same people and civilizations that it wants to describe (pp. 280-281).

Furthermore, Bhabha (1994) also talks about “the desire for the Other” and how the locations of “the Self and Other […] are partial; neither is sufficient unto itself”, which means that “identification […] is only ever the problematic process of access to an image of totality” (pp. 72-73). According to Otto (1999), Bhabha goes one step further than Said by claiming that the dichotomy between the West and the Other is not as monolithic or widespread as this author may indicate, “making the colonial relationship a site that is potentially disruptive of the certainties and hierarchies that it purports to create” (p. ix). On the other hand, this desire for the other that Bhabha discusses is not an equal process for the two sides. Gregory (2004) explains this by using the metaphor of the coin and claiming that “although the coin is double-sided, however, both its faces milled by the machinations of colonial modernity, the two are not of equal value” (p. 4). This leads to the fact that “modernity produces its other, verso to recto, as a way of at once producing and privileging itself” (Gregory, 2004, p. 4).

Through the approaches of these postcolonial scholars, the link between imperialism and international law appears more complex than what is hinted at by authors who focus specifically on the legal aspects of inequality in the international order. The construction of the Other is a process that draws upon an original fear of what is foreign to us and the need to protect ourselves from that which is unknown. By failing to break down these ingrained aspects of human nature critically and instead deciding to use them to gain the upper hand over others, we fail to understand the discriminatory features of the system we live in and the violence that this discrimination signifies for others and for us as well. In NNP, this is particularly true since, as argued by Biswas (2014), the discriminatory regulations established by such a system, while benefitting “a [certain] global ordering function”, do not solve the global issue of nuclear weapons (p. 74).

Methodology

The theories selected marry a methodology that is based on an overarching analytical framework and three methods. The analytical construction of sovereign (in)equality in international law used by Simpson (2004) is the starting point for the analysis of this study. Within this framework, case selection related to the anti-pluralism concept of Simpson’s (2004) theory has included, at first, a simplified plausibility probe rooted in the most similar case study approach. Afterwards, the result of this plausibility probe was narrowed down to a diverse case study design. Discourse analysis has been chosen to see how Simpson’s (2004) anti-pluralism comes about in Western discourse on NNP directed towards the states chosen through case selection.

Simpson’s (2004) structuring of how sovereign (in)equality is constructed represents the overarching analytical framework of the research. As already mentioned, Simpson (2004) starts the process by addressing the nineteenth century when Western imperialist expansion was at its peak (p. 56). This author then explains how this imperialist experience has influenced both exercises of legalized hegemony and the concept of anti-pluralism in the international system, leading to the production of sovereign (in)equality in the three spheres that constitute this principle of international law: formal equality, legislative equality, and existential equality, with the latter two being the most affected by unequal dynamics (Simpson, 2004, p. 56).

Of all of these concepts, only anti-pluralism[1] is considered in the present research, and it will be explored through the differentiation of states conceived by John Rawls into liberal, illiberal domestically/liberal in foreign relations, and outlaw (Simpson, 2004, p. 295)[2] with some case studies. Indeed, it is through a discussion on anti-pluralism that the discriminatory practice within the group of states outside of the United Nations’ permanent five can be observed. The initial argument is that countries that currently do not comply with the regime in place (North Korea, Iran, India, Pakistan and Israel) are treated unequally among them despite all belonging to the group of NNWS and that this discrimination depends on which of the three categories devised by Rawls (1993) they belong to, and not on their individual colonial experiences. Notably, one of these states, Iran, presents a shift in how it has been treated by the West, which seems to be connected to the 1979 revolution and its consequent change of category. Case selection is explained next.

The case selection process starts after some initial observations on NNP non-compliant cases, which have led to the formulation of additional arguments. In particular, this author claims that unfair treatment is not related to the logical assumption of non-compliant states adhering to the NPT or not or pursuing a nuclear program directed towards developing nuclear energy or nuclear weapons. Consequently, the tentative initial hypotheses presented are as follows: 1) stigmatization used by the West in the nuclear field is not related to the targeted state’s adherence to the NPT or to the pursuit of nuclear energy versus nuclear weapons; 2) the West tolerates the nuclear weapons programs of liberal and illiberal/liberal in foreign relations states despite them not complying with the NNP order in place, while outlaw states are stigmatized for it; 3) such unequal treatment is inherent to the way imperialism has shaped international law as a system, but it is not strongly related to the individual experiences of colonialism/imperialism of non-compliant countries.

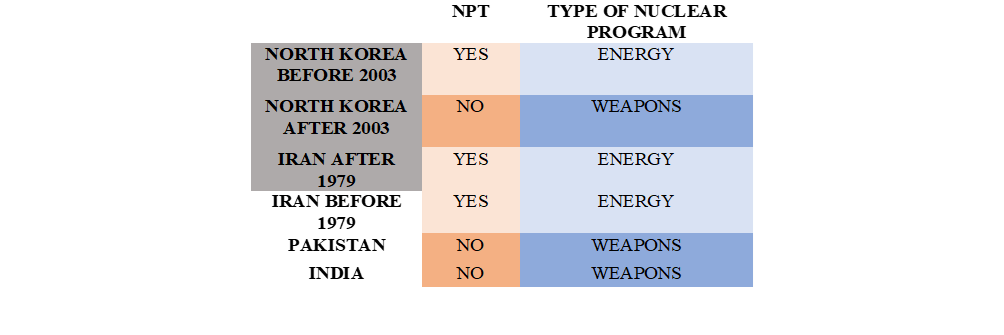

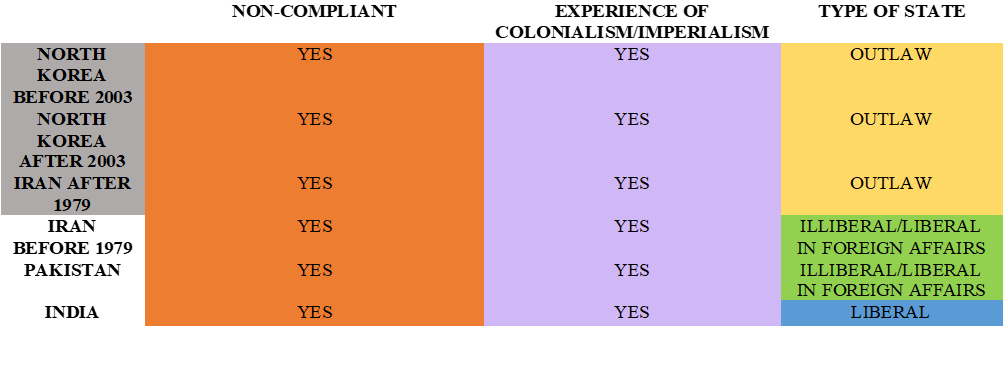

The arguments and hypotheses suggested are strengthened after carrying out a plausibility probe based on a simplified most-similar case study approach to look at possible causes of unequal practices towards these countries and thus check the validity of the chosen theoretical approach. The probe used is limited by the available units that have developed their nuclear programs until current times and have also shown non-compliance. It first consists of a table that tackles the formal side of the inquiry, thus the connection between the presence of non-compliant states in the NPT and the aim of their nuclear programs (energy/weapons) (Table 1). A second table then embodies the simplified most-similar case study design, showing some of the variables (inspired by the theoretical framework) that may be linked to different levels of tolerance of the nuclear programs of the mentioned countries (Table 2).[3]

If we observe the two tables, the countries in gray are those that have been recognized as having been stigmatized by the West, namely North Korea, both before and after leaving the NPT, and Iran after the revolution. On the other hand, the countries in white are those whose nuclear development has been tolerated, these being Iran before the revolution, Pakistan and India. The variables considered in the first table are only of a formal legal nature (NPT status, type of nuclear program). The variables of the second table combine legal concerns (non-compliance) with some elements extracted from the theories that seem intuitively crucial to understanding the politics of nuclear inequality, these being the experience of colonialism/imperialism and the association to one of Rawls’s (1993) categories of states.

We shall begin by considering the formal perspective and, therefore, by looking at the first table (Table 1). When comparing the first three cases with the stigmatizing outcome (North Korea before 2003, North Korea after 2003, Iran after 1979), we can see how neither the legal differences related to their presence or absence in the NPT nor the peaceful or military aim of their nuclear programs can explain such outcome, as there is no constant pattern that would represent the assumption that an illegal status and/or a riskier nuclear weapons development would be connected to international stigmatization. The same can be said within the group of countries in white, as most of them not only have not signed the NPT, but they have also pursued allegedly more concerning nuclear weapons programs (with the exclusion of Iran before 1979, which presents opposite values in the two variables (NPT, type of nuclear program)).[4] Taking this into account and comparing both the group of countries in gray and the group in white, the causes of their different outcomes do not seem to be found in their legal or nuclear statuses. This would be in agreement with our first hypothesis: stigmatization by the West in the nuclear field is not related to adherence to the NPT or not or to the pursuit of nuclear energy versus nuclear weapons.

Moving on to the second table representing the simplified most-similar case design, all countries are similar as they are non-compliant and have experienced Western colonialism or imperialism (Table 2). Thus, the lenient treatment reserved to India, Pakistan, or Iran before the revolution in opposition to the opposite treatment reserved to North Korea and Iran after the revolution cannot be explained in terms of the continuation of neo-colonial power dynamics in these cases as a result of past experiences with colonialism/imperialism. The difference in treatment seems to be more in line with the membership of these units to the different categories of states identified by Rawls (1993), a categorization that has influenced the generation of our second hypothesis: the West tolerates the nuclear weapons programs of liberal and illiberal/liberal in foreign relations states despite them not complying with the NNP regime in place, while outlaw states are stigmatized for it. Therefore, the combination of the previous findings would be in accordance with our final hypothesis: unequal treatment in the nuclear field is inherent in the way imperialism has shaped the international law system as a whole, but it does not seem to be related to the individual experiences of colonialism/imperialism of non-compliant countries.

Although this last hypothesis has been tentatively proven right, this author does not believe that a postcolonial understanding of the chosen topic is unfit for this study. In fact, postcolonial theories are still needed as a guiding star to understand the way in which colonial discourses and power structures have continuously been present in NNP, and not as a way to prove the relationship between single colonial experiences and present inequalities. Moreover, in the actual analysis of the diverse case study that will be explained next, it will be seen how the production and reproduction of “the Other” and paternalistic attitudes that postcolonialism explores still permeate anti-pluralist discourses in the international system, especially when outlaw states are involved, but not only in those cases. Accordingly, the overarching research question when it comes to inequality and NNP should not be the classical can the subaltern speak? that Spivak (1988) has famously proposed, but more on the lines of what kind of subaltern can speak (in the nuclear realm)?

After carrying out the plausibility probe, the case study has been narrowed down. Before that, the main hypothesis has been refocused; in particular, it has been oriented towards the idea that the unequal treatment of the West towards NNP non-compliant states may be related to the categorization of such states as a result of persisting imperialist dynamics in the system of international law. To test this hypothesis, different types of states will be considered through the diverse case study approach.

A diverse case study design entails choosing one typical case for each of the categories already introduced: liberal, illiberal domestically/liberal in foreign relations, and outlaw states. This allows us to understand the way in which the West tolerates the nuclear weapons programs of non-compliant states depending on their category. The chosen cases are Iran before 1979 (illiberal/liberal), after the revolution (outlaw), and India (liberal). The inequality present in the treatment of each category of state will be examined through the analysis of political discourse.

Materials

The empirical evidence used derives mainly from primary sources. Such primary sources have helped to observe whether Simpson’s (2004) idea of the interrelation between anti-pluralism and sovereign equality can be empirically found in international politics and law and, most importantly, whether Rawls’s (1993) anti-pluralist conceptualization of the international system which divides states into categories could be a plausible way of understanding the contrasting treatment by the West when it comes to different NNP non-compliant states. Accordingly, research efforts have been concentrated on executing a discourse analysis of mostly speeches and statements of political and diplomatic representatives of mainly the US and, to a slightly lesser degree, of France, the United Kingdom (UK), and the European Union (EU) in regard to NNP and the cases of Iran and India.

The choice of analyzing politicians’ and diplomats’ speeches and statements from these countries relates to the fact that these states are not only some of the main representatives of the so-called “West” but also three of the five NWS within the NPT. Thus, it is believed that their narrative strongly guides imperialist discourse on NNP law, allowing such discourse to move towards stigmatization in the case of Iran after 1979 or towards tacit tolerance of the nuclear weapons program and/or support in relation to civilian nuclear power when it comes to India and Iran before the revolution. As a result, this language-based empirical evidence will allow us to comprehend how discrimination within the discriminated (meaning NNWS) is constructed in the nuclear sphere.

Iran Before the Revolution: The Illiberal/Liberal Case

The initial encouragement of the civilian pursuit of nuclear energy by Tehran until 1979 was represented not only by the conclusion of agreements on nuclear cooperation between Western countries and Iran but also in the political discourse that surrounded this cooperation. The discourse was characterized by a warm depiction of relations between the West and Iran, an emphasis on the similarities between the two sides, including in the NNP field, and praises to the Shah and his efforts to improve the situation of the country. The following analysis mostly considers political discourse from the US because of its greater availability over that of France, the UK and the EU.

At the time of President Eisenhower, when nuclear cooperation between Western countries and Iran was at its initial stage, relations between the US and Iran were depicted positively. This is seen in Eisenhower’s (1959) use of expressions such as “the cordial warmth of the reception that I received upon the streets of your beautiful city — have all been heartening assurances that our two countries stand side by side [emphasis added]” and “we see eye to eye when it comes to the fundamentals which govern the relations between men and between nations [emphasis added]”. The inclusion of Iran among those countries that adhere to what Rawls (1993) would call “law of peoples” is clear here.

Other examples of positive statements on Iran are those of President Johnson. This is seen during his toasts with the Shah, where he expresses “the full measure of all of our respect as well as our deep affection” and regards the leader of Iran as “an old friend, not just an old friend of ours, but of the United States” (Johnson, 1968). Other US Presidents, such as Nixon (1970), also mentioned to the Shah the importance of “these exchanges with you and the relationship they reflect”. The same is done by President Carter (1977) when he says that US-Iran relations signify “a close friendship that’s very meaningful to all the people in our country”. On the other hand, President Ford (1975) emphasizes the importance of US-Iran ties because “in an interdependent world, we remain deeply grateful for the constructive friendship of Iran, which is playing a very important role in pursuit of a more peaceful, stable, and very prosperous world”.

In the nuclear field, stress on common understandings of NNP mirrors the recognition of similar values in the language used towards Iran. In a letter to the Iranian leader, President Ford wrote the following:

It is well known that under your leadership Iran has played a leading role in supporting the Non-Proliferation Treaty and other efforts to abate the spread of nuclear weapons. I know that you and I share the same desire to foster the goal of non-proliferation. I believe that Iran and the United States may have a unique opportunity to provide vital international leadership in helping to ensure that the sensitive aspect of the nuclear fuel cycle evolves in a manner that reassures the world.

(G. Ford, personal communication, 1976)

The ambition of the US to turn the case of Iran into an example of good practice in NNP is again evident in a memorandum circulated within the White House: “Our approach to the Shah will be on the basis of seeking his commitment to a major act of nuclear statesmanship: namely, to set a world example by foregoing national reprocessing in favor of the multinational concept or possibly some other concept having the same effect.” (B. Scowcroft, personal communication, 1976a)

However, in another memorandum, concerns over the protection of US interests when it comes to the support of nuclear cooperation with Iran is emphasized, leaving aside the praise of Iran as a beacon of hope in global NNP efforts: “The President is anxious to see negotiations of the civilian nuclear accord resumed with Iran under terms that will clearly foster US non-proliferation interests, promote US-Iran interests, advance our domestic nuclear objectives, and stand a good chance of mutual acceptance.” (B. Scowcroft, personal communication, 1976b). From this statement, it would seem that the encouragement and the compliments directed towards Tehran in the nuclear sphere serve as a window dressing that hides the significance of Iran for Washington’s interests.

When it comes to the portrayal of the Shah, the approval of the US towards the deeds of the Iranian leader in light of the progress of his country fills the narrative of Washington’s leaders. Ford (1975) engages in this type of rhetoric when he asserts that “the progress that you have made serves as a superb model to nations everywhere” and that “the leader whose vision and dynamism has brought Iran to this stage, His Imperial Majesty, is clearly one of the great men of his generation, of his country, and of the world”. The same is affirmed by President Carter (1977), who also compliments Iran’s leader by declaring that “the transformation that has taken place in this nation is indeed remarkable under your leadership” and stressing that “because of the great leadership of the Shah, [Iran] is an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world [emphasis added]”.

Nevertheless, what this narrative also hides is a welcoming of Iran’s transformation from a state of uncivilization towards one of modern advancement. President Johnson (1968) engages in this account of Iran when he says that “years ago, His Imperial Majesty determined to break the grip of poverty and disease and ignorance in his own ancient land [emphasis added]”. Ford (1975) uses more subtle language when he implicitly addresses Iran’s change towards a more elevated status by conveying that “Iran has moved from a country once in need of aid to one which last year committed a substantial part of its gross national product to aiding less fortunate nations”. Lastly, Carter (1977) mentions the Americans living in Iran “who work in close harmony with the people of Iran to carve out a better future for you, which also helps to ensure, Your Majesty, a better future for ourselves”. The portrayal of Iran as a country in need of help and the US as the hero willing to give such support is visible in Carter’s words.

In conclusion, the warm depiction of Iran-US relations, the emphasis on common grounds in values and interests, including in the NNP field, and the compliments to the Shah and his country’s progress are still characterized by imperialist and paternalistic connotations. It is natural to wonder whether, once commonalities crumble, positive attitudes could also dissolve, influencing support for nuclear cooperation with Iran. An answer to this query may be given by Eisenhower (1959) when he reminds Iran that, although the US wishes to “work with you for peace and friendship, in freedom”, he wishes to highlight the term “freedom — because without it there can be neither true peace nor lasting friendship among peoples”. The incorporation of Tehran among the US’s circle of partners seems to remain conditional on the internal and, thus, external status of the country vis-à-vis the accepted conceptualization of the society of states.

Iran After the Revolution: The Outlaw Case

The Iranian revolution of 1979 overthrew the rule of the Shah, and Iran became an Islamic republic led by Ayatollah Khomeini. These events changed the status of Iran vis-à-vis the West, and thus also the standing of the country within the international community. In particular, relations between the US and Iran were damaged after the hostage crisis of 1980. These changes influenced Western discourse on Iran and its nuclear development, leaving behind the warm pre-revolution tones. The characteristics of this new discourse have been stigmatization through an emphasis on the sponsorship of Iran towards terrorism and on its human rights record, the dehumanization or “Othering” of Tehran’s regime, and the use of threatening language and punitive measures. In this section, we will see how these characteristics are found in Western political narratives and their implications in shaping the Iranian nuclear issue.

The link between Iran and terrorism is mentioned by President Reagan (1986), who conveys that “at the heart of our quarrel has been Iran’s past sponsorship of international terrorism”. Dominic Raab, UK Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs, uses more subtle language when more recently he referred to the “destabilizing activity that [Iran] sponsors” (as cited in Coleman, 2021, para. 16). President Clinton explicitly associates terrorism with the nuclear threat when he says that “to do nothing more as Iran continues its pursuit of nuclear weapons would be disastrous”, “and to stand pat in the face of overwhelming evidence of Tehran’s support for terrorists would threaten to darken the dawn of peace between Israel and her neighbors” (as cited in Wright, 1995, para. 5). The same is done by Trump (2020) when he declares that “Iran has been the leading sponsor of terrorism, and their pursuit of nuclear weapons threatens the civilized world [emphasis added]”, automatically excluding the country from the latter idea.

Bush (2002) then reaches the ultimate step, which is the establishment of a connection between terrorism, nuclear weapons and human rights, and he does so by claiming that “Iran aggressively pursues these weapons and exports terror, while an unelected few repress the Iranian people’s hope for freedom”. This is also achieved by Trump (2019) when he suggests that “the regime is squandering the nation’s wealth and future in a fanatical quest for nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them”.

The portrayal of Iran’s outlawness does not only include links between terrorism, nuclear weapons and a poor human rights record, but it is also reinforced by an “Othering” practice. An instance of this practice is seen in Obama (2015), who labels Iran as a “ruling regime [that] is dangerous and it is repressive”. Bush (2007) also depicts Tehran as a government that is “defiant as to the demands of the free world”, and in particular to the demands related to NNP. Once again, by not adhering to these demands, Iran is excluded from the idea of the “free world”. Moreover, Bush’s (2002) previous inclusion of Iran within the “axis of evil” also puts the country in a position of an outsider to what is understood as acceptable international behavior.

Nonetheless, it is once again President Trump who uses the most colorful descriptions of the rogue state. Trump (2019) talks about the Iranian government as one “whose record of death and destruction is well known to us all”. This negative representation goes in crescendo until the Iranian state ends up becoming a quasi-monstrous creature that pursues “bloody ambitions” (Trump, 2018) and is characterized by its “bloodlust” (Trump, 2019). Furthermore, Iranians are depicted as stereotyped uncivilized people who “conduct ritual chants of ‘Death to America’” and even “traffic in monstrous anti-semitism” (Trump, 2019). In regard to the Iranian nuclear development particularly, this is described by using the concept of “the lunacy of an Iranian nuclear bomb” (Trump, 2018), which, as seen before, “threatens the civilized world” (Trump, 2020). This depiction refers to the volatility of the regime, which cannot be trusted with nuclear weapons.

The sort of direct language used by US leaders to construct the outlawness of Iran seems not to be particularly found in the discourse of France, the UK, and the EU. Nevertheless, if the US is better at giving discursive momentum to the configuration of the pariah state, European countries are very much present when it comes to displaying paternalistic offers to help Iran get “back on track”. By doing this, they end up implying the same rhetoric as the US. This rhetoric allows a depiction of Tehran’s regime as being in need of help to recover its status, both in relation to its human rights record and adherence to NNP law, among other areas. The backside of this offer is a disguised implication that if the desired transformation (as understood by the West) is not achieved, threatening language and punitive measures will be used to constrain rogue behavior.

An instance of this point is seen in the European discourse. Mogherini (2016) exhibits in her speeches the aspiration of the EU to advance relations with Iran in several spheres, among which are human rights and civilian nuclear cooperation. Cooperation in these two particular areas is implied to be unilateral in nature despite being hidden among more reciprocal fields such as trade or the environment (Mogherini, 2016). On the other hand, the High Representative also suggests that “for Iran to fully benefit from the lifting of sanctions, it is also important that it overcomes obstacles related to economic and fiscal policy, business environment and rule of law” (Mogherini, 2016). The normalization of relations with Iran and the internal recovery of the country is, once again, conditional on its ability to be in line with certain standards set by the West. Moreover, the narrative of the EU also hints that not even the lifting of sanctions can cure Iran’s internal problems.

UK Prime Minister Cameron is more direct about what his administration hoped to obtain from negotiations with Iran. Cameron says that there are two objectives in these negotiations: “step one: we’ve got them away from a nuclear weapon; step two is to now engage with them directly about these issues and seek changes in their behaviour on these issues too” (as cited in Press Association, 2015, para. 4). By “these issues” he means terrorism and “the problems they’ve contributed in the region” (as cited in Press Association, 2015, para. 4). While Cameron refers to changing only the external behavior of Tehran, the British Committee for Iran Freedom is blunter when it advises that the government of the UK “should […] recognize the democratic aspirations of the Iranian people and their right to change the regime for a better future” (British Committee, 2020). The nuclear issue is thus not the only element at stake in Western narratives on Iran. Imperialist and postcolonial connotations are still found in Western political discourse around the Iranian nuclear issue, especially in relation to specific demands for change towards the direction shown by the West.

Stigmatizing practices targeting Iran reach their peak with the use of threatening language and punitive measures when rogue behavior is not corrected. Threatening language is employed by Macron (2020) when he warns at the UN that “we will provide answers to Iran’s ballistic activities and its destabilizing activities in the region”. Such language is used by Obama (2015), who cautions that “Iran would not be allowed to acquire a nuclear weapon on my watch, and it’s been my policy throughout my presidency to keep all options — including possible military options — on the table to achieve that objective”. It is found in Trump’s (2018) rhetoric, who threatens Iran by saying that “if the regime continues its nuclear aspirations, it will have bigger problems than it has ever had before”, while he also reassures “the long-suffering people of Iran” that “the people of America stand with you”. The idea of the “American savior of the oppressed” is a powerful instrument to back up this kind of statements.

Concerning punitive measures, these have been mainly represented by nine key UNSC resolutions and consequent and other sanctions beyond the UNSC framework. These sanctions have targeted critical nuclear technology and manufacturing materials, as well as specific persons and even financial institutions, and they have also established an arms embargo. In addition to official sanctions, unofficial punitive measures have also been taken against Iran, as seen in the case of the cyberattacks that broke down several nuclear centrifuges. The fact that Western states seem to have been behind the attack says a lot about what the West is willing to do to restrain what is considered unacceptable conduct in the international system.

To conclude, we have seen how stigmatization is constructed in the case of Iran through stress on the link between the regime, its nuclear development, terrorism and human rights, as well as a dehumanizing practice that depicts Tehran’s regime as a monstrous creature that endangers the civilized world. While these narratives are mostly found in the discourse of the US, European countries engage in a more classic postcolonial communication that offers help to Iran for it to transform and be reinstated in the international community. Finally, if Tehran does not take the West’s preferred course of action, the use of threatening language and punitive measures is used to signal that Western countries will not tolerate rogue behavior and will restrain such behavior. This will be done while considering “the long-suffering people of Iran” (Trump, 2018).

India: The Liberal Case

Despite the international outcry that followed India’s nuclear tests in 1974 and 1998, political responses to the weaponization of New Delhi’s nuclear program were not comparable to the stigmatization that Iran after 1979 has experienced. This is seen in the dichotomous character of these reactions, meaning that while public condemnation was at first displayed, this was often accompanied by milder confidential responses or even by messages of support for the success of India’s nuclear detonations. Such practices were present even in 1998 when the gravity of the situation led to the one and only UNSC resolution on the matter. Moreover, while in the case of Iran post-revolution, the presence of evidence revealing the harsh criticism of the nuclear ventures of these states exists, the case of India is characterized by a scarcity of negative language. Lastly, with time, India has been accepted as an NWS despite still not being part of the NPT, and nuclear cooperation with the country has progressed until the present.

Examples of these mechanisms are seen in how, after 1974, the US put up a number of punitive measures on India while never completely severing relations with the country. The wish to maintain these relations and pardon New Delhi is perceived in former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s belief that, since the test had already taken place, “public scolding would not undo the event” (as cited in Kamath, 1999, para. 37). Moreover, after the test, he still referred to India as having “a special role of leadership in South Asian and in world affairs”, and he also claimed that “there is no reason to fear a powerful and strong India, and still less reason to prevent it from being so” (as cited in Kissinger Bids India, 1974, para. 14-15).[5] At no point did the Secretary of State engage in stigmatizing language; on the contrary, India’s tests are almost treated as an accepted fait accompli.

Mild criticism was only shown when Kissinger appealed to India’s “accommodation and restraint” and when he stressed that “the United States is of the view that countries capable of exporting nuclear technology should agree to common restraints, on a multilateral basis which would further the peaceful but inhibit the military uses of nuclear power” (as cited in Kissinger Bids India, 1974, para. 13; 19). Nevertheless, he also conveyed that “we take seriously India’s affirmation that it has no intention to develop nuclear weapons” (as cited in Kissinger Bids India, 1974, para. 19-20). The level of trust towards India’s government in Kissinger’s narrative is nowhere to be found in the previous case of Iran after the revolution.

If US discourse in 1974 still maintained a mild level of disapproval, France directly sided with India, as demonstrated by the telegram sent by André Giraud, head of the French Commission for Atomic Energy, which congratulated New Delhi for the test (Le Monde, 1974). In another telegram, French ambassador to India Jurgensen also wrote, “Indians are particularly pleased because France has abstained from all unfriendly judgments and they believe that France is herself well-placed to understand the Indian position in this domain” (Telegram from French Ambassador, 1974).

In 1998, the condemnation was more palpable, both in terms of discourse and the sanctions that were applied. Clinton (1998b) denounced India’s tests by saying that “India’s action threatens the stability of Asia, and challenges the firm international consensus to stop all nuclear testing” and by asking the country to sign the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT). On another occasion, President Clinton criticized New Delhi by pointing out that its actions were “eroding the barriers against the spread of nuclear weapons, discouraging nations that have chosen to forswear these weapons, encouraging others to keep their options open” (as cited in Orr, 2000, para. 4). Disapproval was also shown by the UK’s and France’s representatives who expressed their “dismay” and the “deeply regrettable development” of India’s tests (UN, 1998).

However, this initial disapproval did not lead to the characterization of India as an excluded outlaw. On the contrary, words of understanding and closeness to the Indian government were displayed in Western discourse. Clinton (1998a) considered India’s tests as possibly “an isolated event”, portraying the behavior of the country as a misstep. The US President also praised India’s Prime Minister for his “depth of understanding” and “his genuine concern that he both protect the security of his country and do nothing to upset the decades long effort now the world has been making toward non-proliferation” (Clinton, 1998b). Then, a few years later, Clinton seemed to settle the matter by calling upon India’s right to make its own sovereign decisions. He does so when he indicates that “only India can know if it truly is safer today than before the tests” and “only India can determine if it will benefit from expanding its nuclear and missile capabilities if its neighbors respond by doing the same thing” (as cited in Orr, 2000, para. 8).

When it comes to France, if in 1974 the country sided with New Delhi without hesitation, the same also occurred in 1998. On this occasion, French President Chirac regarded the refusal to include India in the international nuclear system as an inconsistency that needed to be amended (as cited in Sood, 2019, para. 5). France also reached out to India immediately and started a “strategic partnership” with the country (as cited in Sood, 2019, para. 5). A spokesperson for the French government even said that “the French Government does not encourage the Americans to pursue sanctions because this is surely not the right method for attempting to assure that India joins those nations wishing to sign the non-proliferation treaties” (as cited in India Nuclear Tests, 1998). It is interesting to see how sanctions are not perceived as the proper method to restrain India, but they are widely used towards Iran.

Despite India’s nuclear tests, its relations with the West were soon recovered, and its nuclear status has been progressively accepted as an undeniable fact. Under the Bush administration, the two countries were already “natural partners”, and India was regarded as “a democracy that protects rule of law and is accountable to its people” and an “ally in the war against extremists and radicals” that “like America, […] is committed to fighting the extremists, defeating their hateful ideology, and advancing the cause of human liberty around the world” (Bush, 2006). Secretary of State Rice (2008) also applauds the balanced relationship between the two countries, which “now stand as equals, closer together than ever before [emphasis added]” and together “protect and promote […] human rights and human dignity, democracy, liberty, and the rule of law”. These statements show how no “Othering” practice is undertaken in the case of India.

The Elysée also completely normalized nuclear relations with New Delhi in 2008 when it signed an agreement on civilian nuclear cooperation after India was absolved by the NSG. It was the first state to do so. With time, nuclear cooperation between the two countries was deepened with new pacts, and French discourse mirrored the positive status of France-India nuclear relations. This is seen in the words of French President Sarkozy, who professed France’s friendship towards India by saying that “we support India to be part of any nuclear forum that it wishes to participate in” (as cited in NDTV Correspondent, 2010).

Other similar agreements on nuclear cooperation were also signed with the UK. Minister Pat McFadden said during the conclusion of one of these agreements that the deal reflected “our strong non-proliferation commitments” (as cited in Ormsby, 2010, para. 4). On a similar occasion later on, British Prime Minister Cameron and Prime Minister Modi regarded the agreement as “symbol of [our] mutual trust” aiming to “strengthen safety and security in the global nuclear industry” (UK and India, 2015, para. 5).

The previous analysis shows the differences between the cases of Iran before and after the revolution and that of India. Despite a certain level of public outrage for India’s weaponization of its nuclear program and the pressures for the country to sign relevant international agreements on the matter, Western states have generally tolerated and accepted the establishment of the country as progressively becoming one of the unofficial NWS. This is despite the fact that India is not yet a party to the NPT or the CTBT. In Western political narratives, the government of New Delhi is depicted as a trustworthy equal that should be in charge of dealing with the consequences of its nuclear weapons program. Also, shared democratic values between India and the West position the former as deserving a level of understanding that Tehran never received after 1979. The evidence of the Indian liberal case thus potentially confirms the initial hypothesis, which affirms that in the NNP regime, liberal anti-pluralism outshines colonial experiences and assigns stigmatizing practices only to the outlaw category. What this means for sovereign equality will be discussed in the conclusion.

Conclusion

The results obtained through the discourse analysis related to the practice of liberal anti-pluralism highlighted by Simpson (2004) from a postcolonial perspective have allowed us to identify a different side to the common narrative on NNP that supports the inequalities devised by such a regime. The study of the cases of Iran before and after the revolution and India has allowed us to see that the language surrounding these nuclear programs seems to adhere to Rawls’s (1993) categorization of states and subsequent levels of “nuclear tolerance”. Iran after 1979, as an outlaw case, is stigmatized for its nuclear development no matter its nature, while Iran before the revolution and India, as illiberal/liberal and liberal cases, respectively, are not. The analyses of these cases have thus potentially confirmed the hypothesis that the unequal treatment of the West towards non-compliant states within the NNP order may be related to the categorization of such states as a result of persisting imperialist dynamics in the system of international law as a whole. These case studies have also given us a response to the question of what kind of subaltern can speak (in the nuclear realm)?

In the outlaw case of Iran after the revolution, stigmatization has occurred through a linkage between nuclear development, human rights violations, and even terrorism and has been reinforced by the dehumanization of the regime and the use of punitive measures and threatening language to constrain rogue behavior. The problem with these practices is not the need to signal disapproval and hold political leaders accountable for terrible acts that jeopardize not only global peace and security but also the lives of their people. The issue is that the West paternalistically places itself as the donor of solutions that would tackle nuclear development and human rights, particularly in a way that conforms with its own view. It does so by not addressing a series of contradictions within its own actions that require a certain level of self-reflection.

Some of these contradictions are the fact that, by continuously defining power in nuclear weapons terms and exclusively reserving the potential use of this material capability for themselves, NWS and Western NWS, in particular, may create a desire for the Other to become the nuclear Self. By denying this possibility, they subtract importance from the security needs of the subaltern state,[6] and they arguably make a case for stronger national efforts of these subaltern states to find a way to fill this gap. Furthermore, when it comes to human rights, events such as the war in Iraq have shown how human rights discourse can also become a tool to legitimize violence and illegal neo-colonialist ventures. This again boosts security demands in countries like Iran or North Korea, especially as they, too, like Iraq, were part of the famous “axis of evil” concept. Additionally, the fact that sanctions often affect the most fragile segments of society in target countries, despite efforts to narrow down these measures in order to avoid harming the local population, is another instance of how human rights narratives may be inconsistent.

In the illiberal/liberal case of Iran before the revolution, nuclear development was praised in light of the shared values and interests that bonded Tehran and the West. Nevertheless, despite the tolerant attitude of the West towards Iran’s civilian nuclear efforts, this relationship seemed to remain conditional on the maintenance of a certain type of internal and external behavior of the country, as ordained by the accepted view of the so-called international community. Moreover, Western rhetoric, in this case, was still characterized by imperialist and paternalistic undertones. The combined theoretical perspective thus highlights how the West still maintains a postcolonial apparatus that shapes the fate of certain states from a position of power and even how Western countries may look the other way from the actions of illiberal/liberal states despite them not fully complying with human rights standards. The question arises: what level of human rights violations is acceptable not to isolate a country from the society of states? The fact that the West calls for the respect of these rights while tolerating a certain level of abuse depending on the situation is another discrepancy revealed by the chosen theories.

In the liberal case of India, despite initial public outcry for India’s nuclear tests and pressures for the country to sign relevant international agreements, Western states have accepted India as an unofficial NWS. Common democratic values shared by India and the West appear to have been the basis upon which understanding of New Delhi’s (responsible) position has been more profound than that of Tehran’s. The fact that India has not yet entered treaties like the NPT may be a point of debate in holding the country accountable for legal obligations that it has never subscribed to in the first place. However, NNP is not just made up of legal texts but also a series of norms which point towards a general obligation towards complete nuclear disarmament. India, as a possessor of nuclear weapons, also has the duty to comply with this obligation. Lastly, the West, as one of the main supporters of the NNP regime, must assume its responsibility and power in shaping the global security environment in unequal terms. This inequality for postcolonial India has been rectified with the weaponization of its nuclear program and the rejection of treaties that may hinder its newly obtained equal status.

Iran before the revolution and India have thus been able to speak, or better, to act, which, as indicated in the plausibility probe discussion, also shows that individual experiences of colonialism/imperialism are not related to stigmatization in NNP. However, what is behind this agency is still very much entrenched in how imperialist dynamics in international law have found their way into the postcolonial space. This has come with a price that has not made the world safer or more equal in any way, nor has it considered local opposition or alternatives to nuclear proliferation. Most importantly, this reality calls for a deeper analysis of the role of those who support the current NNP regime, even among non-Western societies.

Finally, what these mechanisms and the power dynamics behind them signify for sovereign equality is its weakening. If imperialist dynamics in international law diminish sovereign equality, this could possibly lead to certain countries being stripped of the basic legal defense against new types of neo-colonial intrusion. This violence could trigger responses that, particularly in the nuclear sphere, would render the world more unstable. Furthermore, by hegemonically promoting a hierarchical type of sovereign equality, the West and its supporters end up perpetuating an unfair international system by failing to listen to dissenting voices. This means that the origins of the crude realities of many countries, and even the causes behind their illegal nuclear programs, will never find an appropriate solution, or they could just be tackled through violent means by labeling them as outlaw cases. Lastly, by failing to examine the challenging forces to the NNP system critically and concentrating on maintaining a superior position in such a regime, Western NWS (and others) neglect their own obligations towards nuclear disarmament and cannot but be unsuccessful when asking other states to comply with these same obligations. Therefore, while a weakening of sovereign equality could be thought to serve the interests of the strong initially, it actually ends up endangering the international system as a whole.

Tables

Notes

[1] Anti-pluralism “denies certain states the right to participate fully in international legal life because of some moral or political incapacity such as lack of civilization, absence of democracy, or aggressive tendencies” (Simpson, 2004, p. 232).

[2] Rawls’s original denomination of these three categories is well-ordered/liberal societies, well-ordered/non-liberal societies (or hierarchical societies), and outlaws. Liberal and hierarchical societies share a consensus on the same “law of peoples”, which is a “family of political concepts along with principles of right, justice, and the common good that specify the content of a liberal conception of justice worked up to extend to and apply to international law” (Rawls, 1993, p. 43). Hierarchical societies are those which are peaceful and not expansionist, have a certain degree of legal legitimacy internally, and respect a certain level of basic human rights (Rawls, 1993, pp. 50-52).

[3] As one of the variables is related to the experience of colonialism/imperialism, the complicated history of the state of Israel makes its incorporation in the study difficult, and thus it has been excluded. States that have given up their nuclear programs are also left out, as only those that have developed their nuclear power until the present will be addressed.

[4] Despite concerns, so far there is no evidence that Iran has successfully developed nuclear weapons.

[5] Although discourse in the aftermath of the 1974 nuclear test pointed at the idea that a stronger India should not be feared, a memorandum for the US President from the same year indicates the need to avoid the insinuation “that India’s status as a world power has been substantially enhanced as a result of its nuclear test” (R. S. Ingersoll, personal communication, 1974, p. 20).

[6] See Ayoob (2015).

References

Anghie, A. (2005). The War on Terror and Iraq in Historical Perspective. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 43(1/2), 45-66. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol43/iss1/3

Anghie, A. (2006). The Evolution of International Law: Colonial and Postcolonial Realities. Third World Quarterly, 27(5), 739-753. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4017775

Anghie, A. (2012). Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511614262

Anghie, A. (2014). Towards a Postcolonial International Law. In P. Singh & B. Mayer (Eds.), Critical International Law: Postrealism, Postcolonialism, and Transnationalism (pp. 123-142). Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199450633.001.0001

Anghie, A. (2016). Imperialism and International Legal Theory. In A. Orford & F. Hoffmann (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Theory of International Law (pp. 1-18). Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/law/9780198701958.003.0009

Ayoob, M. (2015). Defining Security: A Subaltern Realist Perspective. In K. Krause & M. C. Williams (Eds.), Critical Security Studies: Concepts and Strategies (pp. 121-146). Routledge.

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The Location of Culture. Routledge.

Biswas, S. (2014). Nuclear Desire: Power and the Postcolonial Nuclear Order. University of Minnesota Press.

British Committee for Iran Freedom. (2020, April). Written evidence submitted by the British Committee for Iran Freedom (UKI0015). https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/2807/pdf/

Bush, G. W. (2002, January 29). Text of President Bush’s 2002 State of the Union Address. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/onpolitics/transcripts/sou012902.htm

Bush, G. W. (2006, December 18). President Signs U.S.-India Peaceful Atomic Energy Cooperation Act. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2006/12/20061218-1.html

Bush, G. W. (2007, May 24). Bush gives speech on Iraq, Iran . Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dhZLTvAjbbQ

Carter, J. (1977, December 31). Tehran, Iran Toasts of the President and the Shah at a State Dinner. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/tehran-iran-toasts-the-president-and-the-shah-state-dinner

Chowdhry, G. & Nair, S. (Eds.) (2002). Power, Postcolonialism and International Relations. Routledge.

Clinton, B. (1998a, May 17). (17 May 1998) US President Bill Clinton said at a press conference on Sunday (17/05) that Pakistan had not carried out a nuclear test according to information he has received . Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tspBaikgETs

Clinton, B. (1998b, May 22). (22 May 1998) President Bill Clinton on Friday urged India to end its testing of nuclear weapons . Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=smm6WukI5ck

Coleman, C. (2021, September 3). UK Government policy on Iran: the Iran nuclear deal and dual nationals. House of Lords Library. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/uk-government-policy-on-iran-the-iran-nuclear-deal-and-dual-nationals/

Dann, P. & Hanschmann, F. (2012). Postcolonial Theories and Law. Verfassung und Recht in Übersee / Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America, 45(2), 123-127. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43256847

Eisenhower, D. D. (1959, December 14). Address to the Members of the Parliament of Iran. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-members-the-parliament-iran

Ford, G. (1975, May 15). Toasts of President Gerald R. Ford and the Shah of Iran. https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/speeches/750261.htm

Ford, G. (1976, February 21). Letter to the Shah of Iran [not readable]. In Iran – The Shah (1) (pp. 34-35). National Security Adviser’s Presidential Correspondence with Foreign Leaders Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/document/0351/1555814.pdf

Gregory, D. (2004). The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Israel/Palestine, Iraq. Blackwell.

India Nuclear Tests, 11 & 13 MAY: International Comment. (1998). The Acronym Institute. http://www.acronym.org.uk/old/archive/spint.htm

Ingersoll, R. S. (1974, December 4). U.S. Nuclear Non-proliferation Policy. In National Security Study Memorandum (NSSM) 202 on Nuclear Proliferation (pp. 16-21). History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Nixon Presidential Library, National Security Council Institutional Files, Study Memorandums (1969-1974), Box H-205. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115172

Johnson, L. B. (1968, June 11). Toasts of the President and the Shah of Iran. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/toasts-the-president-and-the-shah-iran-4

Kamath, P. M. (1999). Indian Nuclear Tests, Then and Now: An Analysis of US and Canadian Responses. Strategic Analysis: A Monthly Journal of the IDSA, XXIII(5). https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/olj/sa/sa_99kap02.html#note20

Kissinger Bids India Join In Curbing Atomic Arms. (1974, October 29). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/10/29/archives/kissinger-bids-india-join-in-curbing-atomic-arms.html

Le Monde, ‘Our Neighbors and Other Countries have Nothing to Fear from India, Declares Madam Gandhi’. (1974, May 28). History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Archives des Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, La Courneuve, Carton 2252, Questions atomiques : explosion indienne, 1973 – June 1980. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/117748

Macron, E. (2020, September 22). Emmanuel Macron speaks at UN General Assembly (22 Sept. 2020). https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/united-nations/news-and-events/united-nations-general-assembly/unga-s-75th-session/article/emmanuel-macron-speaks-at-un-general-assembly-22-sept-2020

Mogherini, F. (2016, July 14). Declaration by Federica Mogherini on behalf of the EU on the one year anniversary of the JCPOA. http://www.federicamogherini.net/declaration-by-federica-mogherini-behalf-of-the-eu-the-one-year-anniversary-of-the-jcpoa/?lang=en

NDTV Correspondent. (2010, December 6). India-France sign agreement on civil nuclear cooperation. NDTV. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/india-france-sign-agreement-on-civil-nuclear-cooperation-441194

Nixon, R. (1970, July 30). Letter from President Nixon to the Shah of Iran. US Department of State Archive. https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/frus/nixon/e4/65074.htm

Nye, J. S. (1985). NPT: The Logic of Inequality. Foreign Policy, 59, 123-131. https://doi.org/10.2307/1148604

Obama, B. (2015, August 5). Remarks by the President on the Iran Nuclear Deal. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/08/05/remarks-president-iran-nuclear-deal

Orford, A. (2003). Reading Humanitarian Intervention: Human Rights and the Use of Force in International Law. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511494277

Orford, A. (2011). The Past as Law or History? The Relevance of Imperialism for Modern International Law. IILJ Working Paper 2012/2 (History and Theory of International Law Series), U of Melbourne Legal Studies Research Paper, 600, 1-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2090434

Ormsby, A. (2010, February 13). UK, India sign civil nuclear accord. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-britain-nuclear-idUSTRE61C21E20100213

Orr, D. (2000, March 23). Clinton urges India to outlaw nuclear testing. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/clinton-urges-india-to-outlaw-nuclear-testing-1.258686

Otto, D. (1999). Postcolonialism and Law? Third World Legal Studies, 15(1), vii-xviii. http://scholar.valpo.edu/twls/vol15/iss1/1

Press Association. (2015, July 17). David Cameron: we will not relax pressure on Iran. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/17/cameron-we-will-not-relax-pressure-on-iran

Rasulov, A. (2017). The Concept of Imperialism in the Contemporary International Law Discourse. Forthcoming, In J. d’Aspremont & S. Singh (Eds.), Concepts for International Law. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3006655

Rawls, J. (1993). The Law of Peoples. Critical Inquiry, 20(1), 36-68.

Reagan, R. (1986, November 13). Address to the Nation on the Iran Arms and Contra Aid Controversy – November 13, 1986. https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/address-nation-iran-arms-and-contra-aid-controversy-november-13-1986

Rice, C. (2008, October 10). Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Indian Minister of External Affairs Pranab Mukherjee At the Signing of the U.S.-India Civilian Nuclear Cooperation Agreement. https://2001-2009.state.gov/secretary/rm/2008/10/110916.htm

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Said, E. W. (1994). Culture and Imperialism. Vintage Books.

Scowcroft, B. (1976a, n.d.). Letter to the Shah. In Iran – The Shah (1) (p. 37). National Security Adviser’s Presidential Correspondence with Foreign Leaders Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/document/0351/1555814.pdf

Scowcroft, B. (1976b, February 4). Next Steps in our Negotiation of a Nuclear Agreement with Iran. In Iran – The Shah (1) (pp. 40-41). National Security Adviser’s Presidential Correspondence with Foreign Leaders Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/document/0351/1555814.pdf

Simpson, G. (2004). Great Powers and Outlaw States. Cambridge University Press.

Sood, R. (2019, August 27). How Delhi and Paris became friends. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/research/how-delhi-and-paris-became-friends-54811/#:~:text=In%20January%201998%2C%20President%20Jacques,relationship%20to%20%E2%80%9Cstrategic%20partnership%E2%80%9D.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the Subaltern Speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture (pp. 271-313). Macmillan Education.

Spivak, G. C. (1999). A Critique of Postcolonial Reason. Harvard University Press.

Starski, P. & Kämmerer, J. A. (2017). Imperial Colonialism in the Genesis of International Law – Anomaly or Time of Transition? Journal of the History of International Law, 19, 50-69. DOI: 10.1163/15718050-12340078

Tannenwald, N. (1999). The Nuclear Taboo: The United States and the Normative Basis of Nuclear Non-Use. International Organization, 53(3), 433-468. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2601286

Telegram from French Ambassador Jean-Daniel Jurgensen to the French Foreign Ministry in Paris. (1974, May 23). History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Archives des Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, La Courneuve, Carton 2252, Questions atomiques: explosion indienne, 1973- June 1980. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/117749

Trump, D. (2018, May 8). Trump’s Iran nuclear deal speech full text. https://www.vox.com/world/2018/5/8/17332494/read-trump-iran-nuclear-deal-speech-full-text-announcement-transcript

Trump, D. (2019, September 24). Hear Trump’s full remarks on Iran from his UN address . Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=duNq3D6MHkc

Trump, D. (2020, January 8). Remarks by President Donald Trump on Iran, released by the White House. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-iran/

UK and India sign nuclear collaboration agreement (NCA). (2015, November 13). King’s College London. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/uk-and-india-sign-nuclear-collaboration-agreement-nca#:~:text=On%2012%20November%202015%2C%20the,UK%20and%20India%2C%20including

United Nations (UN). (1998, May 15). Disarmament Conference Members Condemn India Nuclear Tests [Press Release]. https://www.un.org/press/en/1998/19980515.dcf332.html

Wright, R. (1995, May 1). President Says He Will Ban Trade With Iran. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-05-01-mn-61015-story.html

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Nuclear Proliferation and Humanitarian Security Regimes in the US & Norway

- A Biopolitical and Necropolitical Analysis of Nuclear Weapon Proliferation

- Halakhah and Omnicide: Legality of Tactical Nuclear Weapons under Jewish Law

- Is There a Right to Secession in International Law?

- International Law on Cyber Security in the Age of Digital Sovereignty

- A Rules-Based System? Compliance and Obligation in International Law