This article is part of the US-China Dynamics series, edited by Muqtedar Khan, Jiwon Nam and Amara Galileo.

In November 2021, Antony Blinken made his maiden voyage as Secretary of State across the Atlantic to engage with sub-Saharan Africa. His first stop was to Kenya, where he met with President Uhuru Kenyatta to discuss regional security issues, primarily violence, terrorism, and political transitions in Sudan, Somalia, and Ethiopia (Voice of America). After this two-day visit, he travelled to Abuja, Nigeria, where he addressed the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and noted some of Nigeria’s strengths—namely the nation’s perception as the “Giant of Africa,” its robust economy, engaged civil society, and even its cultural influence through the global diffusion of afrobeats music and its most notable culinary specialty—jollof rice. Finally, in Senegal, Blinken reaffirmed the U.S.’ desire to continue developing the U.S.-Senegal friendship which was first established six decades ago, and he urged the nation to continue modeling good governance and leading progress on strengthening democracy and security in West Africa (U.S. Department of State Press Release). According to Voice of America, the diplomatic effort via this multi-country tour was “aimed at raising America’s profile as a key player in the region as it competes with China” (Voice of America). The efforts marked a clear departure from the Trump administration’s apparent neglect of the continent.

Just a year later in December 2022, the Biden administration continued to demonstrate this renewed commitment through hosting a U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit. This was only the second of such events in U.S. history, the first of which was executed under the Obama administration in 2014. Leaders from 49 African states attended the proceedings and engaged in dialogues on various topics relevant to the continent, some of which included climate change, food security, democracy and governance, human rights, and cooperation in space (Fabricius, 2022). Importantly, at this summit, the U.S. pledged to invest 55 billion USD in Africa over the next three years (Bureau of African Affairs, 2023). While improving the U.S.’ relationships with key players on the continent may be strategically beneficial in of itself, there is clearly a greater sense of urgency to reaffirm some long-lasting relationships due to the increasing competition imposed by China. The present chapter seeks to explore prospects for the future U.S.-Africa-China nexus, and more specifically, it will survey whether Africa will become a region of contention in the U.S.-China rivalry or whether it will present an opportunity for shared continental hegemony and strategic cooperation. I will first delineate the history of U.S. and Chinese engagement in Africa, then outline some key issue areas pertaining to Africa in which China and the U.S. could either cooperate or compete, and finally present my projections for the years to come.

History of U.S. Engagement in Africa

Prior to World War II, the United States had little interest in engaging with the African continent (Cohen, 2020). Because it was colonized, Washington had scant impetus to communicate with the African nations themselves—rather, if there was conflict or some special interest, U.S. leadership would simply address the colonial powers (the British, French, and Portuguese). Up until this point, Africa was of little geostrategic interest to the States. However, this changed during World War II when the United States recognized the geographic importance of the continent and its necessity for sending supplies from the West to the East. In addition to the U.S.’ need for African airfields, of increasing importance was also uranium oxide from Congo which American engineers used to develop nuclear weapons. This period marked the beginning of Washington’s recognition of the need for a true Africa foreign policy strategy.

After its successes in World War II, Washington took an anti-colonialism stance in the mid-1900s and pressured the colonial powers to withdraw from African countries. Specifically, the Atlantic Charter which was signed by the British and America agreed to a post-war order with no territorial aggrandizement, freer exchanges of trade, disarmament, and a respect for the sovereignty of nations (The Atlantic Conference & Charter, 1941). As anti-colonial pressures grew and it appeared that African nations were preparing for independence, current U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower recognized the need to develop a stable Africa policy. The early post-African independence period was characterized by experimentation with various policies and strategies. The Nixon administration focused primarily on global issues rather than regional, so policymakers limited bilateral assistance to Africa to ten “concentration countries” which showed potential for development (Office of the Historian). A change of pace occurred with the Carter administration, when there was a strategic shift away from development initiatives to more localized efforts addressing basic human needs. This included water projects and health initiatives aimed at reducing malaria and childhood diarrhea. Although these initiatives were successful, Carter’s overall Africa policy is widely believed to have been unsuccessful (Geritz, 2017).

The Clinton presidency brought renewed vitality to U.S.-Africa relations, specifically through the enactment of the African Growth Opportunities Act (AGOA) in May 2000. This act was purposed to increase economic ties between the regions through duty-free access to U.S. markets, and its success has led to its renewal until the year 2025. George W. Bush then introduced a health initiative in 2003—PEPFAR—to combat the AIDS and HIV epidemic. This was (and remains today) the largest initiative by a government to address a single disease, experiencing bipartisan support in Congress and immense success in preventing deaths in Africa. President Obama built upon the initiatives of his predecessors by addressing another need on the continent—electricity—through the Power Africa program which aims to bring 30,000 new megawatts to the continent and 60 million new electricity connections (USAID). Another notable achievement was the Young African Leaders Initiative which targets emerging leaders on the continent through public diplomacy efforts to provide education, training, and engagement with the United States. Cohen (2020) argues that the Trump administration was characterized by continuity with his predecessor, Obama, despite attempts in other areas to overturn the Obama-era policies. One notable success was the United Nation Ambassador’s trip to the Democratic Republic of Congo where Ambassador Haley successfully persuaded the increasingly autocratic President Kabila to hold multiparty elections. Additionally, the Trump administration introduced the Prosper Africa Program which searches out opportunities for U.S. investors to make deals with African investors. To date, this program has seen 800 deals closed between the U.S. and African nations and an estimated $50 billion in exports and investments (Prosper Africa). Finally, the Biden administration has courted the continent through hosting the 2022 Leaders Summit, increasing diplomatic tours in the region, and releasing a specific and concrete Africa policy titled the “U.S. Strategy toward sub-Saharan Africa” in August 2022.

In sum, the U.S. has meaningfully engaged with sub-Saharan Africa for over eight decades. The areas of interest have predominantly included building economic relationships, addressing health problems such as malaria and AIDS, and facilitating development. While there have been accusations of neglect toward Africa in previous administrations, recent actions by Biden’s diplomatic team suggest that the U.S. has reaffirmed its commitment to progress and development in Africa through aid and mutual collaboration.

History of Chinese engagement in Africa

Sino-African relations began in the medieval period, specifically through trade via naval fleets who traveled to the Northeast coast of Africa (Shinn, 2019). Under the Ming Dynasty, mariner Zheng He voyaged around the Horn of Africa, giving gifts of precious metals, porcelain, and silk, and receiving in return giraffes, ostriches, zebras, and other novelty items (Tsai, 2002). In the early 20th century, contemporary engagement in Africa was initiated through the development of a relationship with the South African government due to the high presence of Chinese immigrants (Shinn, 2019). The first years of the Mao Zedong era were characterized by a preoccupation with domestic affairs and the development of the new People’s Republic of China. Then in the 1950s, relations were amplified through the signing of multiple bilateral trade agreements (China-Africa Economic and Trade Cooperation). A turning point occurred when Premier Zhou Enlai embarked upon a ten-country tour of the continent in 1963 and 1964, the first Chinese statesman to visit Africa. The purpose of this trip was to develop diplomatic relations as well as to “strengthen…leftward-leaning Afro-Asian solidarity,…counter the effects of Soviet propaganda,…spread an image of China as a major power,… [and] gain the first-hand knowledge necessary for formulating China’s policy toward Africa” (Scalapino, 1964). During this period, both assistance and foreign direct investment to the continent were limited due to the economic difficulties of the new People’s Republic. It is estimated that the total amount of aid China sent to Africa under Chairman Mao was the equivalent of 2.4 billion USD, with the Tanzanian and Zambian railroad being the largest project (Shinn, 2019). Sino-African economic engagement would not increase until the 1990s. The era of Mao was also characterized by an increase in Chinese military assistance in the 1970s, including the training of African soldiers—nearly three thousand from thirteen countries over the span of 1955 to 1979 (Shinn & Eisenman, 2012). The major beneficiaries of this assistance were Cameroon, Egypt, Sudan, Tunisia, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire). China provided military weaponry such as aircraft, boats, tanks, and ammunition. In sum, the first seven decades of the 20th century were characterized by slow progress in facilitating political, economic, and military ties between China and Africa.

Post-Mao, Deng Xiaoping oversaw another tour to Africa in 1982 by Premier Zhao Ziyang, a replica of the Zhou Enlai trip two decades earlier which was purposed to confirm China’s commitment to the continent. During his voyage, Ziyang outlined the new Chinese strategy toward Africa based on four principles: equality and non-interference; more impactful economic relations; a greater variety of projects; and an increase in self-reliance (Xuetong, 1988). The transition to Jiang Zemin in the early 1990s led to a notable increase in high-level visits by Chinese politicians to the continent, including President Zemin’s visits to East, West, and Southern Africa (1996) and Prime Minister Li Peng’s visit to seven countries (1997) (Xuetong, 1988). This period was also characterized by the formation of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 1999, of which the objectives were to strengthen friendship and promote cooperation between the regions (FOCAC). To date, the organization has hosted three major summits, the last of which was in Dakar, Senegal in November 2021. Hu Jintao’s administration was marked by a continuation of the initiatives of his predecessors—FOCAC, development aid, and conventional weapons supplying, with a massive increase in trade from the equivalent of $10 billion USD to $180 billion USD in just one decade, overtaking the U.S. as Africa’s largest trading partner in the year 2009 (Shinn, 2019). Finally, Xi Jinping has been accused of employing an “aggressive” form of diplomacy, particularly in Africa (Myers, 2020). His official platform for the region includes enhancing political mutual trust and equality, deepening cooperation in international affairs, strengthening financial cooperation, increasing technology cooperation and knowledge-sharing, and promoting peace and security (China Daily). Another major strategy has been including Africa in the new Belt and Road Initiative. This has been a successful venture, with 39 African countries listed on the official website as participants (Risberg). Overall, Chinese engagement with Africa has far outweighed that of the U.S. China has historically focused on commercial transactions and high-level attention in order to gain trust and access to Africa’s leaders and the continent’s valuable natural resources. While it is clear that the U.S. and China have been the most impactful actors in facilitating Africa’s growth and development, it remains to be seen whether this continental dominance will lead to cooperation or competition.

Areas for Cooperation

Based on an assessment of U.S.-Africa and Sino-Africa relational history, the current global context, and the grand strategies of each region, I propose that there are five major areas in which the three regions could cooperate to achieve common goals (some insights were drawn from Sany & Sheehy, 2021). In the present section, I will outline each issue area and the reasons in which I submit that cooperation is possible, if not likely.

Climate change

According to NASA, “the effects of human-caused global warming are happening now, are irreversible on the timescale of people alive today, and will worsen in the decades to come” (NASA). Climate change is caused by an increase in greenhouse gases such as water vapor, nitrous oxide, methane, and carbon dioxide which block heat from escaping the atmosphere. This can have the effect of accelerated sea level rise, disruption of precipitation patterns, droughts, floods, and intense heat waves. Although the entire globe is affected by this phenomenon, it has been projected that sub-Saharan Africa is becoming increasingly vulnerable to climate change, specifically through the threat of food and water insecurity, population displacement, and fatalities and economic consequences associated with extreme weather events (United Nations). Treiber suggests that foreign partners should work with African nations to create plans for carbon-neutral economies by 2050 (2021). He points to collaborative focus areas as (1) methane capture, (2) new technology pilots, and (3) green energy minerals development. Climate change is one issue area which there is not only an opportunity for collaboration, but an existential necessity.

Managing public health crises

Historically, the United States has been the greater investor in public health programs. These have included local health initiatives under the Jimmy Carter administration and the tremendously successful PEPFAR program under George W. Bush. The U.S. has also partnered with various African countries to combat malaria, reduce infant and child mortality, mitigate Ebola outbreaks, and distribute vaccines (Office of the Press Secretary). On the other hand, it has been more contested as to whether China’s health assistance to African countries is inspired by altruistic or opportunistic motives (Lin et al. 2016). While Beijing may not have developed as extensive of programs as the United States, China has offered generous support in the areas of sending medical teams and health-related equipment, offering scholarships, and training African medical personnel (Xinhua 2018). A detailed list of Chinese health assistance offered since 2000 can be found in Table 1 of Killeen et al., 2018. Rather than working separately, China and the U.S. could combine efforts to address the most pressing health concerns—one of which is the COVID-19 pandemic and the issue of vaccine distribution.

Mitigating terrorism

The activity of insurgent and militant Islamic groups in Africa has increased in the past several decades. Boko Haram is one such group which primarily affects Africa’s most populous country—Nigeria. The terrorist organization has killed nearly 350,000 Nigerians and displaced three million citizens since 2009, its ultimate aim to overthrow the Nigerian government, destroy Western influence in Nigeria, and install an Islamic state in the nation (Global Conflict Tracker). Al-Shabaab has also had a significant presence in Africa, specifically East Africa, with a similar mission to that of Boko Haram. These groups contribute to issues of displacement, food crises, famines, and death. Terrorism at large is a clear threat to the peace and stability of Africa. Whether China and the U.S. employ a strategy of defeating these groups militarily or they promote better governance and development as a means of mitigating terrorism, this is an issue which costs all three regions economically and in human lives. A greater collaborative effort between the U.S. and China in this area may be the key to defeating wide-scale terrorist activity once and for all.

Promoting peace and security

The United States has been the predominant contributor to United Nations peacekeeping operations. Of the present 12 peacekeeping operations currently ongoing, half of them are on the continent of Africa (Western Sahara, Mali, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, Sudan, and South Sudan) (United Nations Peacekeeping). In the 2020-2021 period, the United States contributed 27% of the budget for peacekeeping operations while China contributed 15% (United Nations Peacekeeping). Both nations are also part of the United Nations Security Council, suggesting that they have interest in the “maintenance of international peace and security.” (United Nations Peacekeeping). Peace and security are paramount to the attainment of other goals in Africa, as there is evidence that conflict stunts economic growth, specifically by disrupting investment and trade, destroying human capital, and causing permanent losses of output (Newiak). The United States and China are already working collaboratively, if indirectly, through the United Nations Security Council, however, the creation of more localized joint security programs could be incredibly effective at stabilizing the particularly volatile regions.

Development and infrastructure

Finally, in the areas of development and infrastructure, China and the United States have already established themselves as key external partners. Asefa and Kai note that “most of Africa’s developmental problems are caused by domestic factors that need local solutions, [but] there is room for external partners to collaborate and to address these challenges for mutual benefit” (2021). The United States has focused its efforts on bringing development through improved public health infrastructure, attempting to promote more political stability, and engaging in counter-terrorism operations, while China has approached the issue predominantly through infrastructure investment connecting African countries and cities. While substantial progress has been made over the past several decades, greater cooperation in the area of development and infrastructure-building should be considered. A collaborative approach could take advantage of the U.S.’ strength in humanitarian considerations, China’s strength in infrastructure and rapid economic development, and African governments’ contextual knowledge of the most effective and efficient ways to achieve development.

Areas for competition

The aforementioned section illustrates that collaboration between China and the U.S. is indeed possible in a multitude of key issue areas in Africa. However, it is indisputable that Beijing and Washington are competitors in the global arena, embroiled in a ‘great power competition’ that will likely not reach a conclusion any time soon. As China continues its aggressive diplomacy on the continent and the Biden administration recommits to deeper engagement in Africa, there are three predominant categories of influence in which competition might emerge—economically, culturally, and politically.

Economic dominance

Perhaps the most apparent—and likely—area in which China and the U.S. could compete for dominance in Africa is economically. Overall, in terms of foreign direct investment, the United States was historically the largest external investor. This changed in the year 2011 when China surpassed the U.S., and it remains the largest foreign investor to date.

China’s new Belt and Road Initiative, launched in 2013, has become increasingly concerning to its political rivals, including the U.S. The Belt and Road Initiative is the centerpiece of president Xi Jinping’s foreign policy and economic development strategy, and it is modeled after the former Silk Road trade routes which connected China, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe (Jie 2021). It has been said that, while China is utilizing this project to expand its economic and political power globally, the United States is concerned that “the BRI could be a Trojan horse for China-led regional development and military expansion,” with former President Donald Trump expressing the most vocal opposition (Chatzky & McBride 2020). This infrastructure development includes skyscrapers, railways, airports, and bridges, and it is the projected completion date of 2049. Perhaps the most significant project in Africa is the high-speed railway in Kenya which will run from Nairobi to Mombasa (Jie 2021). China has also funded a major gas pipeline in Nigeria and other projects in Uganda, Ethiopia, and Mali, with a special emphasis on coastal countries (16 in the West, eight in the North and East, and two in Southern Africa), which has created concern as to whether China will exploit these ports for military purposes in the future (Venkateswaran 2020). According to China, only five out of 54 African countries have refused to sign a Memorandum of Understanding regarding the BRI. This suggests that China has gained immense power and influence on the African continent through this foreign policy strategy.

A specific area in which conflict may arise is over the issue of oil. According to Klare & Volman, “Africa is the final frontier as far as the world’s supplies of energy are concerned with global competition for both oil and natural gas…becoming just as intense—if not even more so—than the former” (2006). In recent decades, the United States has beefed up its military aid programs and provided weaponry, equipment, and technical assistance to oil-rich regions such as Nigeria and Angola in order to keep the stability in these areas and protect its assets (Klare & Volman 2006: 299). There is disagreement as to whether China’s increasing military and economic ties to oil-rich African nations is a threat to U.S. national interest. This discussion has subsided in recent years, however, with America’s growing oil independence. However, access to African economies and natural resources is of great importance to both Beijing and Washington, and it could exacerbate tensions between the two regions in the years to come.

Cultural dominance

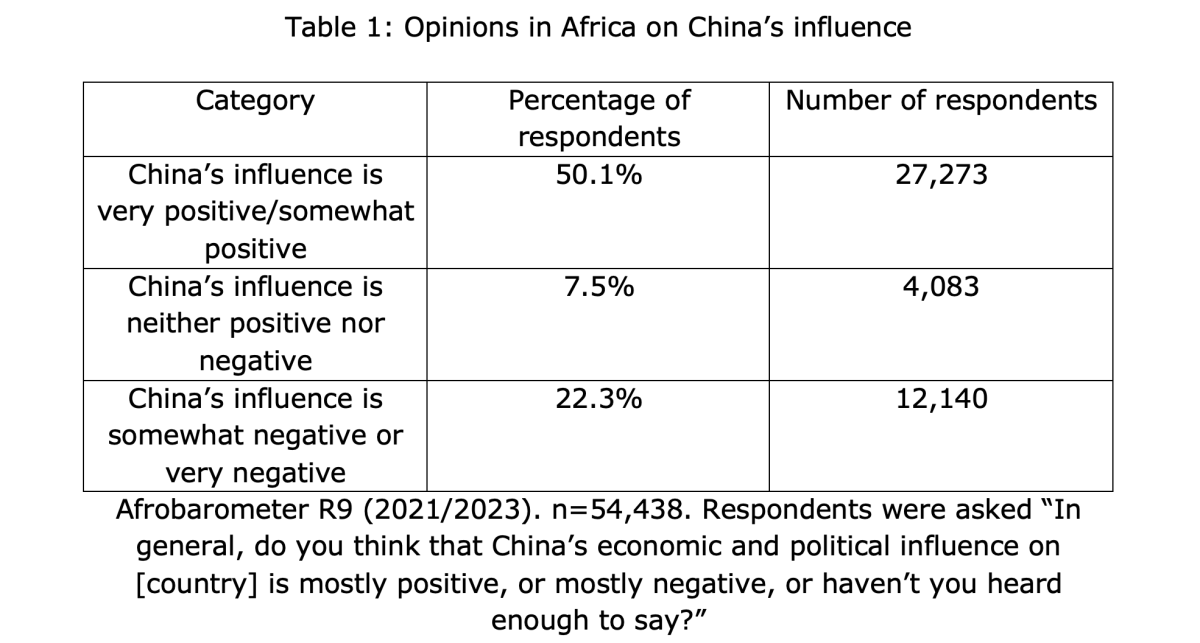

Economic exchange is only one way to build relationships and deepen ties among international partners. Another potentially more subtle strategy is to build soft power, or a term coined by Joseph Nye in which a nation has the ability to persuade, rather than force, through diplomacy, culture, and history. Soft power arguably takes longer to develop, but it can pay dividends for generations through attractiveness and respect for a country’s traditions, culture, values, and pop culture. China already enjoys a relatively positive perception among Africans. A 2014/2015 survey by Afrobarometer, a pan-African research institution which gauges public opinion on various topics, found that the majority of respondents viewed Chinese influence in Africa positively (Table 1). Only 22% of nearly 55,000 respondents reported holding negative views toward Chinese influence. This is likely a consequence of President Xi Jinping’s recent efforts to improve China’s image in Africa. In an interview, Afrobarometer’s CEO Joseph Asunka noted that data on the United States is similar, and generally, “both countries are seen in a considerably more positive light than former colonial powers” (2021).

Some specific ways in which China has worked to develop its soft power and cultural influence in Africa in the 20th and 21st centuries have been through the promotion of Maoist doctrine during the Cold War as well as educational programs like the Confucius Institutes (Haper, 2019). The latter has potentially been the most influential. The Confucius Institute is regarded as one of the largest language and culture-promotion projects ever, although it has been accused of aiding espionage and spreading propaganda (Li 2021). The stated goals of the Institute are to promote understanding of the Chinese language and culture, enhance educational and cultural cooperation, and develop friendships. While many institutes have been closed in recent years in the United States and other Western countries such as Australia, Denmark, Germany, Belgium, France, and Sweden, the Institute’s presence in Africa is said to be “steady and strong” (Mattis, 2012).

The United States has no equivalent to China’s Confucius Institutes in Africa. However, the Department of State recognizes the importance of public diplomacy efforts and consequently created the Young African Leaders Initiative under the Obama administration. YALI is said to be “The U.S.’ signature effort to invest in the next generation of African leaders” (“About YALI”). The initiative is comprised of three major components: the regional leadership centers—located in Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, and South Africa—in which participants can receive leadership training and professional development opportunities; the annual Mandela Washington Fellowship, whereby approximately 700 participants (chosen out of about 50,000 applicants) get flown to the United States to leadership institutes around the country for six weeks during the summer; and finally the virtual YALI network which allows young Africans to connect with one another and gain access to free resources. This is a strategy which will pay dividends in the years to come by creating loyalty and establishing friendships with the African continent’s future leaders.

Both China and the U.S. have sought to increase their soft power and cultural dominance in Africa through cultural exchanges and educational programs. While each country’s soft power capabilities on the continent appear to be neck-and-neck, this particular area of influence is important due to its effect on the next possible arena for great power competition—political dominance.

Political dominance

Because of China’s rapid development and unprecedented ascension as a major global power, developing nations are looking to the Beijing Consensus as an alternative path to achieving economic and political stability. Beijing’s model of ‘authoritarian capitalism’ poses a threat to international norms of liberal democracy being the ideal political system (Kurlantzick, 2013). American politicians worry that “China is playing an increasingly influential role on the continent of Africa, and there is concern that the Chinese intend to aid and abet African dictators…and undo much of the progress that has been made on democracy and governance in the last 15 years in African nations” (quote by Representative Christopher Smith of NJ referenced in Klare & Volman, 2006, p. 305).

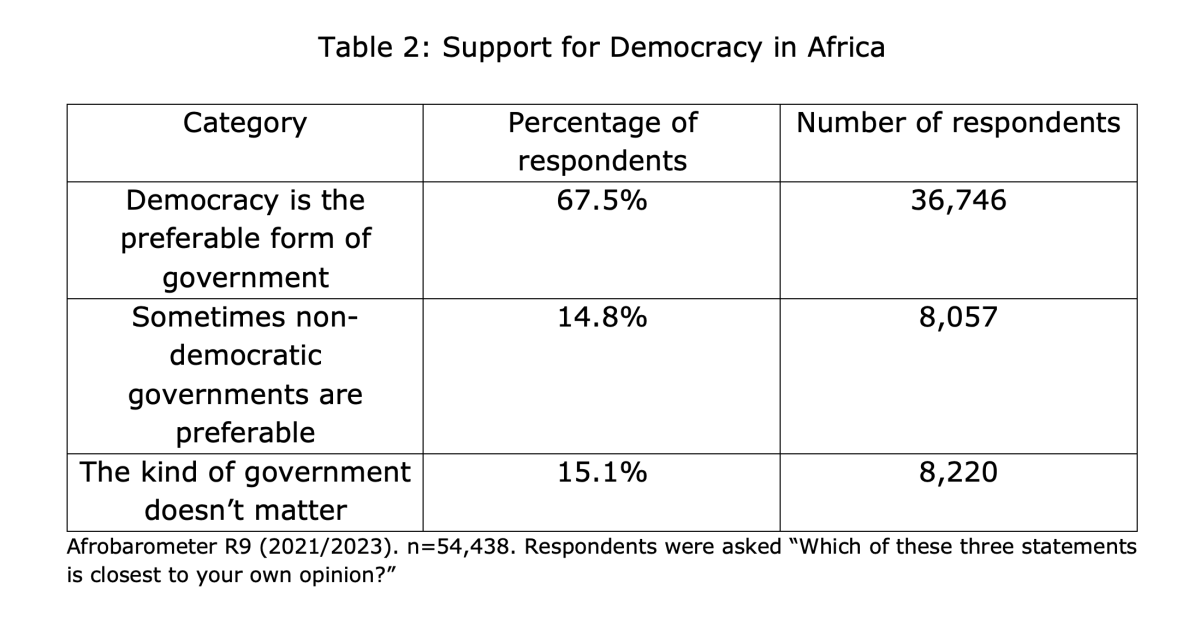

The United States has poured time, material resources, diplomatic efforts, and manpower into stabilizing African governments and promoting democracy on the continent. There is a growing fear that China’s economic success and relative political stability are evidence that there is another path by which developing nations can achieve economic growth and evade transitions to democracy. This may be an area of contention between Beijing and Washington in the coming years. Luckily, democracy remains the preferred form of government for most Africans (Table 2). However, it will be interesting to see how public support for democracy changes over time as China continues its diplomatic efforts on the continent.

Concluding Remarks

It is impossible to capture all the nuances of the U.S.-Africa-China nexus in one web series submission, however my hope is that the reader has gained insight into several key areas to watch in the years ahead to determine whether shared hegemony is indeed possible. In the present paper, I have examined climate change, combatting terrorism, managing public health crises, promoting peace and security, and development and infrastructure as five possible areas for cooperation between China and the U.S. in Africa. On the other hand, quests for economic, cultural, and political dominance on the continent present potential arenas for conflict.

My final prognosis is that competition will be the most likely scenario in the coming decades. As Africa’s population expands to twice its current number by 2050, as regional powers such as South Africa and Nigeria grow in stature in the international arena, and as natural resources grow increasingly scarce elsewhere around the globe, the fight for influence in this vital region will inevitably intensify. I believe that competition will result for two major reasons: (1) China and the U.S.’ fundamentally different value systems; and (2) the grand strategies of each country preclude meaningful cooperation. In the first instance, the U.S. government purportedly stands for liberty, democracy, and human rights, while the Chinese government values communism and authoritarian principles while arguably neglecting human rights concerns. In terms of grand strategy, it is largely unknown as to whether China ultimately desires global hegemony, whether it simply wants global economic dominance, or whether it desires a new multipolar world order alongside the U.S., Europe, and other major international players (Owen 2019). My personal opinion is that China’s behavior points to the former—that Beijing seeks to replace the U.S. as the foremost global power. On the other hand, I believe the U.S.’ grand strategy is to keep China down in order to maintain its status as the world’s number one. If this is the case, this fundamental struggle may prohibit participation in mutually beneficial cooperative projects on the African continent. Of course, it would be remiss to view this as a zero-sum scenario. While competition may be the default mode of interaction within this U.S.-Africa-China nexus, it could very well be the case that the U.S. and China may come together in one or two important areas. For example, with the continuation of the COVID-19 pandemic, the two countries could partner to help distribute vaccines to Africa more quickly and efficiently. While there may be competition in most areas, that does not mean that there cannot be some level of cooperation in others.

In sum, I agree with Judd Devermont’s assertion that “us-vs-them ultimatums” should be avoided (quoted in Smith, 2019). These ultimatums may turn Africans off completely from any sort of engagement with either China or the USA and lead them into more arrangements with other rising powers such as Russia and India. I also believe it is vital to account for African agency in this conversation. Rather than being a passive chessboard on which China and the U.S. wage their geopolitical game, African governments have control over who has access to what and when. The priorities of the African people must be accounted for, and the continent cannot be used a pawn, as it so often has been before. African leaders must avoid exploitative agreements and focus on collaborative and mutually beneficial partnerships that are not laden with hidden costs and future economic burdens. The African continent is an immensely valuable region, and its relationship with China and the U.S. will likely help shape world events in the years to come.

Tables

References

About AGOA. (n.d.). AGOA.info. https://agoa.info/about-agoa.html

About FOCAC. (n.d.) Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. http://www.focac.org/eng/ltjj_3/ltjz/

The Atlantic Conference & Charter, 1941. (n.d.). Office of the Historian. United States Department of State. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/atlantic-conf

Blinken, Antony. (November 19, 2021) .The United States and Africa: Building a 21st Century Partnership [Speech]. U.S. Department of State Press Release.

Blinken Visits Kenya to Discuss Partnership, Regional Issues. (November 16, 2021). Voice of America.

Boko Haram in Nigeria. (n.d.). Global Conflict Tracker. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/boko-haram-nigeria

Chatzky, A. & J. McBride. (January 28, 2020). China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative

China-Africa Economic and Trade Cooperation. (December 2010). https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/cebw//eng/jmwl/t785012.htm

Climate Change is an Increasing Threat to Africa. (October 27, 2020). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/news/climate-change-is-an-increasing-threat-to-africa

Cohen, H. J. (2020). US policy toward Africa: Eight decades of Realpolitik. Boulder, CO, and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

The effects of climate change. (n.d.). NASA: Global Climate Change, Vital Signs of the Planet. https://climate.nasa.gov/effects/

Fabricius, P. (December 9, 2022). Will next week’s U.S.-Africa summit revive relations? ISS Africa. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/will-next-weeks-us-africa-summit-revive-relations

Fact Sheet: U.S.-African Cooperation on Global Health. (August 04, 2014). The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/08/04/fact-sheet-us-african-cooperation-global-health

Franck Gerits, “Jimmy Carter in Africa” History (2017) 102#351, pp 545-547.

Full Text: China’s second Africa policy paper. (December 05, 2015). China Daily. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/XiattendsParisclimateconference/2015-12/05/content_22632874.htm

How we are funded. (n.d.). United Nations Peacekeeping. https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/how-we-are-funded

Jie, Y. (September 13, 2021). What is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)? Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/what-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-bri

Killeen (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6447313/

Klare, Michael and Daniel Volman. “America, China & the Scramble for Africa’s Oil.” Review of African Political Economy 33, no. 108 (2006): 297-309.

Lin et al. (2016) https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/29739081/5135833.pdf

Myers, Steven Lee. (April 17, 2020). China’s Aggressive Diplomacy Weakens Xi Jinping’s Global Standing. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/17/world/asia/coronavirus-china-xi-jinping.html

The United States and Kenya: Strategic Partners. (November 16, 2021). Office of the Spokesperson, U.S. Department of State.

Owen, John M. “Ikenberry, international relations theory, and the rise of China.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 21, no. 1 (2019): 55-62

“Profiles”. Belt and Road Portal. 2 April 2020. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019

Power Africa. (n.d.) USAID. https://www.usaid.gov/powerafrica

Prosper Africa. (n.d.) https://www.prosperafrica.gov

Risberg, Pearl. (n.d.) The Give-and-Take of BRI in Africa. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/give-and-take-bri-africa

Sany, J. & T. Sheehy. (April 28, 2021). Sidestepping Great Power Rivalry: U.S-China Competition in Africa. The United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/04/sidestepping-great-power-rivalry-us-china-competition-africa

Scalapino, R. A. (April 1964). On the Trail of Chou En-Lai in Africa. The Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_memoranda/2009/RM4061.pdf

Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Senegalese Foreign Minister Aissata Tall Sall at a Joint Press Availability. (November 20, 2021). U.S. Department of State Press Release. Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Sheehy, T. & J. Asunka. (June 23, 2021). Countering China on the Continent: A Look at African Views. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/06/countering-china-continent-look-african-views

Shih-Shan H. Tsai (2002). Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press.

Shinn, D. H. (2019). China-Africa ties in historical context. China-Africa and an Economic Transformation, Oxford University Press Oxford. pp, 61-83.

Smith, E. (October 9, 2019). The U.S.-China rivalry is underway in Africa, and Washington is playing catch-up. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/09/the-us-china-trade-rivalry-is-underway-in-africa.html

Treiber, L. (October 19, 2021). Creating an Effective Net-Zero Partnership with Africa. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Vines & Wallace. (September 15, 2021). Terrorism in Africa. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/terrorism-africa

Where we operate. (n.d.). United Nations Peacekeeping. https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/where-we-operate

Xinhua (August 21, 2018). Chinese medical service contributes to healthcare of African people. Xinhuanet. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-08/21/c_137407868.htm

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- In Search of Food Security: US-China Hegemonic Rivalry in Africa

- Rare Earths and Semiconductors in US Policymaking Amidst US-China Rivalry

- Opinion – US-China Rivalry: Moving Closer to the Brink

- India-China Rivalry and its Long Shadow Over the BRICS

- The US-Iran-China Nexus: Towards a New Strategic Alignment

- US-China Dynamics: Competition, Conflict or Cooperation?