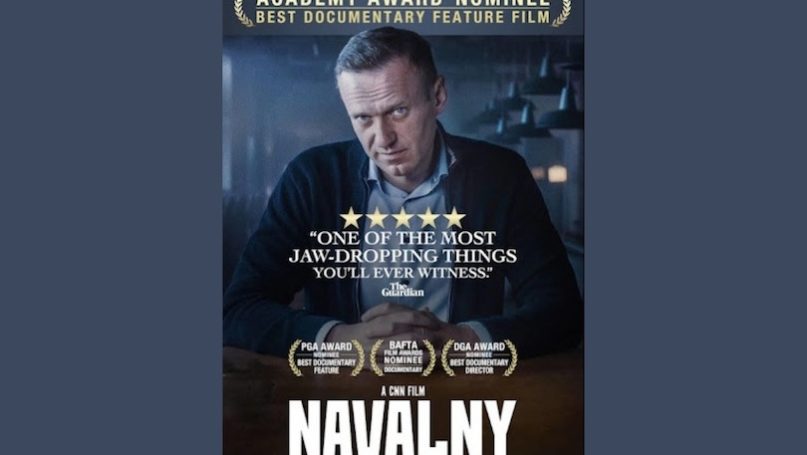

Navalny

Directed by Daniel Roher, 2022

The tragic death of the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny in a remote Siberian labour camp compels this reader to review what is arguably the most valuable extant filmography of a remarkable rights crusader. One should begin this analysis with a caveat that those who worked with Alexei found some of his opinions on such matters as immigration into the Russian Federation, and on the idiosyncrasies of global human rights provision, to be on the conservative side, to say the least. Moreover, his impulsiveness and unyielding commitment to his own courses of action, may have made him as many enemies as friends.

Nevertheless, the vast numbers who braved the tightest of security cordons to publicly grieve Alexei’s death is a tribute of his significance in a post-Soviet landscape where protestors have been systematically eliminated by the Putin regime. This 2022 film, happily portrays Alexei Navalny “warts and all” and is all the more valuable for this reason. Therefore, this review will certainly not read as a work of hagiography.

This 2022 film directed by Daniel Roher and produced by Odessa Rae and others, is a landmark in filmographic achievement in both civic rights and on the Russian Federation in particular. Among those who give extensive testimony in this presentation are Alexei Navalny himself, together with other well-known campaigners such as Yulia Navalnaya, Maria Pevchikh, Christo Grozev and Leonid Volkov. The 98 minutes includes consistently excellent cinematography provided by Niki Waltl, edited by Maya Hawke and others, and with widely acclaimed music from Marius de Vries. The production involved HBO MAX, CNN Films and others, and the film was distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures and Fathom Events.

Navalny premiered on January 25, 2022 at the Sundance Film Festival winning awards at the 95th Academy Awards; Choice Documentary Awards and the 76th BAFTAs. It primarily investigates Navalny’s poisoning. On August 20, 2020, Navalny was poisoned with a Novichok nerve agent, becoming symptomatic during a flight from Tomsk to Moscow. He was taken to a hospital in Omsk after an emergency landing. Still comatose, two days later, he was evacuated to the Charité hospital in Berlin, Germany. The use of the nerve agent was confirmed by five internationally respected agencies, including the UN’s Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and by several certified German laboratories. Navalny blamed Russian president Vladimir Putin for his poisoning. The Kremlin denied involvement, as they have done so with his recent death. For years in the state media, he has been referred to as kogo nikogda ne upominayut, ‘unmentionable’.

In the film, Bellingcat journalist Christo Grozev and Maria Pevchikh, investigator for Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, reveal the details of a Putin plot in what Roher describes as “the story of one man and his struggle with an authoritarian regime”. Roher assembles vast previously unseen footage of a de facto Kremlin fugitive. Navalny’s wife is featured extensively. Bellingcat have pieced together what exactly happened in the leadup to August 2020. The plot is akin to a political thriller movie, except (as Navalny keeps reminding us), “this actually happened”. The content is not just about unprecedented corruption in Russian government but unmasks Russian political façade. Putin is portrayed as an egomaniac.

Navalny thus became a prisoner of conscience, and yet had the courage to return to Russia. Besides fleeting mobile phone and news clips, sparce video of the Novichok poisoning or his subsequent recovery in Russian and German hospitals reportedly exists (his wife explains that she refused to allow him to be photographed during that period). The vital phone call between Navalny and an unwitting Putin agent confirms he was poisoned is caught on film. ‘Let’s make a thriller out of this movie,” suggests Navalny to Roher. “And then, if I am killed, you can make a boring movie of my memory.”

The commentary to the (BBC Two) screening offers up a potted history of Navalny’s pro-democracy activism. At times, he seems both provocateur and investigative journalist. Again, to show he is no saint, the film explores Navalny’s alliance of convenience with the far right. For Navalny, social media is a weapon and a shield. When, for example, he and his wife, Yulia, board the plane that is returning them to Moscow, he “is relieved rather than irritated to be greeted by a forest of filming phones. When you oppose a regime that shrouds its deeds in darkness, there cannot be too much light”. But Navalny undoubtedly overestimated the protection of his fame.

The film lampoons the innate foolishness and unsubtle prejudices of his opponents. At one point, a Kremlin-endorsed talk show scathingly attacks liberals and their “endless homosexuality” as an explanation for Navalny’s weakness and near-death. Putin goes to ridiculous lengths to avoid even saying Navalny’s name. Navalny seems the moral winner throughout. Post-Soviet realpolitik has a way of stamping on narrative justice. As Roher states: “The film ends in a darkness that is all the more pronounced for our knowledge of where Putin is about to take Russia…”

The Russian opposition leader, now assumed to be murdered while serving hard labour as the guest of a Putin penal colony, populates this movie as a natural performer. Mr. Navalny shorthands Putin’s deviousness as “moscow4”: According to Navalny in a clip included as part of the movie, “when a high-ranking intelligence officer under Mr. Putin was hacked—his password was moscow1—he changed it to moscow2. When that was hacked, he changed it to moscow3. This illustrates Navalny’s position that the brutality of the Kremlin is a natural concomitant of gross incompetence and stupidity. His story as portrayed in this film, has a particular resonance in Britain: he survived the brutal events that are the focus of this film, but Briton Dawn Sturgess did not – the blameless British national was fatally poisoned with Novichok on British soil in 2018, as the chaotic byproduct of a bungling attempt by Russian agents to kill former agent Sergei Skripal.

What do we really know of the gruesome fate of the man this film portrays? According to Russian accounts, the 47-year-old took a short walk, collapsed and never regained consciousness. Navalny’s medical condition had deteriorated in his three years in prison. Nevertheless, he appeared well in a court video a day before his death. The weight of international opinion does not tally with Russia’s account of what happened at IK-3, or “Polar Wolf” – one of Russia’s toughest prisons. French Foreign Minister Stéphane Séjourné said Navalny “paid with his life” for his “resistance to Russian oppression”, adding that his death was a reminder of the “reality of Vladimir Putin’s regime”. Navalny’s wife, Yulia, said simply: “We can’t really believe Putin and his government.”

Russia’s Interfax news agency reported that medics spent half an hour trying to resuscitate him. According to prison authorities, doctors were with him within two minutes and an ambulance was available within six. If this was true it would be a record even for the finest clinics in Moscow. In the months after Navalny’s imprisonment on charges of “extremism” and “corruption”, various warnings from his allies and lawyers were issued that his condition was worsening. In 2021, his campaigners had exposed the building of a $1bn palace for Putin on the Black Sea. This movie captures all of this.

Ultimately the least we can say is that Navalny joins the many victims of “sudden Russian death syndrome”. Many were overt Putin critics, and former allies who metamorphosed into threats – such as mercenary leader Yevgeny Prigozhin – or just critics who insulted the Kremlin. Among that last group, Pavel Antov, 65, a “sausage tycoon” who fell to his death. Another was businessman, Vladimir Budanov. Also, Russia’s oil giant Lukoil boss, Ravil Maganov, who plummeted from a hospital window in Moscow. Earlier, Boris Nemtsov, a charismatic opposition leader; Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist who wrote books about Russia’s police state; and Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB agent and critic of Putin, whose tea was laced with polonium-210. In response to this the Russian public hear only crude, State fabrication. Films like this, help compensate for the verification deficit which is surely among the greatest challenges in penetrating the Putin regime. As this review noted at the outset, Navalny will always be remembered as probably Russia’s greatest de-mystifier of state propaganda. It is sad to reflect that his passing bears all the hallmarks of a state-sanctioned killing.