In the field of International Relations, the notion of the “planetary” has gained a strong interest as a framework to rethink relations between States and humanity. Extending far beyond ecological issues and environmental degradation, this concept is not entirely new. During the Cold War, John Herz identified a “planetary mind” under the influence of nuclear threats, which compelled a redefinition of interests that had previously been viewed solely through a national lens (Herz, 1959). In the early 1970s, Harold and Margaret Sprout emphasized the planetary as the rise of ecological consciousness within international relations (Sprout & Sprout, 1971). While the notion is therefore not new, it remains contested. The reception of the manifesto published by Millennium. Journal of International Studies in 2016 is pending (Burke & a., 2016). Revisiting traditional concepts of power and sovereignty, the planetary calls into question humanity’s place on Earth and its responsibilities toward future generations and other forms of life.

Over the past decade, a specific literature has emerged, from the geostrategic risks associated with resources extractions to the exploration of non-western cosmologies that diverge from Westphalian perspectives. This article seeks to offer a modest guide to navigating this literature. It aims to update three representations of the planetary that, to varying extents, shape our understanding of planetary politics: the Nomos of the Earth, the Gaia Hypothesis, and the Spirit of the Earth. Each of these conceptions has different implications. The first envisions the planet as a territory for human conquest; the second perceives an increasingly fierce struggle between humans and nature; the third opens a path to an inner revolution, reexamining how we connect on Earth. It appears that planetary approaches can all be linked, in one way or another, to one of these three representations.

Nomos of the Earth: The Planet through Geopolitics

The concept of “planetary” is often overlooked by proponents of modernity, who view wars primarily as conflicts between States over territory and resources. This perspective aligns with various schools of Geopolitics, emphasizing competition among great powers and the influence of geography. Key figures in this field, influenced by Carl Schmitt’s ideas (Schmitt, 2003), interpret international relations as a continuous cycle of territorial acquisition, viewing the world through a narrow lens focused on land rather than the planet as a whole.

Schmitt’s theory focuses on the “Nomos,” which refers to the division of space throughout history. His view is steeped in Christian theology, suggesting that humans are inherently tied to the earth, which he considers a restrictive element rather than a nurturing one. He distinguishes between land, which he sees as orderly and structured through human labor, and the sea, which he associates with chaos and lawlessness. Schmitt’s disdain for oceans reflects his perspective that they undermine human order and control. He simplifies the planet to land, failing to acknowledge the significance of water and the biological interconnectedness of life on Earth.

This interpretation resonates with contemporary realities, as defense budgets remain historically high, exemplified by the US spending over $1.4 trillion in 2022. These levels are reminiscent of the Cold War era and are unaffected by global crises like the 2008 Financial Crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic. This continuous military expenditure highlights a security dilemma among states, where the pursuit of enhanced military capabilities serves as both a means of securing national safety and a source of insecurity for neighboring states. Innovations in military technology, including advancements in robotics and transhumanist research, further complicate the nature of modern warfare.

Beyond financial investments, shifts in conflict dynamics are evident in common spaces that are accessible but not owned by any single entity. These areas play crucial roles in global flows—international airspace, the high seas, outer space, and cyberspace. Historically dominated by the United States, these spaces are increasingly contested by emerging powers, such as China and Russia, challenging previous monopolies and seeking to assert their influence through maritime claims, anti-satellite technologies, and cyber warfare.

While direct conflict has not yet erupted in these domains, a “state of war” is developing, marked by increasing militarization and the potential for conflict without formal declarations of war. The doctrines of major powers reflect this shift, with Russia advocating for a “new generation war” and China articulating various forms of warfare, including media and psychological strategies.

The reduction of planetary concerns to terrestrial conflicts aligns with the Thucydides’ trap scenario, which illustrates the rivalry between dominant powers, notably between the United States and China today (Allison, 2017). This rivalry is characterized by efforts to control territory and restrict access to common spaces, fueling tensions between shared resources that are meant to be common and those that can be appropriated.

However, this narrow focus on military conflict overlooks the ecological impact of growing military forces. Despite a rising awareness of environmental issues within the military sector, the ecological footprint of armed forces remains substantial, contributing to environmental degradation and the exacerbation of climate change. This raises critical ethical questions regarding the consequences of war on the planet. Additionally, the focus on traditional forms of conflict neglects non-military disputes and alternative conceptualizations of war. Schmitt’s approach primarily addresses confrontations between states, sidelining other forms of conflict. New interpretations of warfare, such as those stemming from ecological concerns, demonstrate that the battle for resources can transcend conventional military engagements. For instance, the ecological dimensions of the Ukraine War in 2022 emphasize the need for sobriety in energy consumption, signaling a potential shift away from reliance on resources from adversarial nations. Nevertheless, this ecological approach remains rooted in a conventional understanding of war, as energy abstinence is viewed primarily as a tool within the context of modern conflicts. It raises questions about whether a broader vision of the planetary can emerge beyond these limitations.

In summary, the prevailing interpretations of the planetary realm, heavily influenced by territorial and militaristic perspectives, tend to obscure the complex interrelations between environmental and geopolitical concerns. A more comprehensive understanding of the planetary requires acknowledging the intricate relationships between humanity, the environment, and conflict, moving beyond the constraints of traditional geopolitical narratives.

Gaia Hypothesis: Considering a New Struggle for Life

According to Hannah Arendt (2018), human life is fundamentally connected to our planet, and this connection is threatened by the actions of homo faber. She argues that the Earth serves as the essential habitat for humanity, emphasizing the danger of annihilating organic life through technological advancements, particularly nuclear weapons. However, the environmental impacts of modern society have since escalated, leading to a concerning acceleration of global change. This acceleration extends beyond the “Great Acceleration” noted since 1945 (McNeill, and Engelke, 2014); it represents a unique historical phenomenon marked by an increasing drive to control and access the world, resulting in heightened life rhythms that affect both personal and societal experiences (Rosa, 2013).

As a consequence of this acceleration, we encounter the concept of planetary limits. Our environment struggles to accommodate human activities and their ecological consequences. According to research, only three planetary boundaries—ocean acidification, ozone layer depletion, and atmospheric aerosol concentration—remain intact. In contrast, limits related to climate change, biodiversity loss, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, land use, and chemical pollution have already been surpassed.

In the 1970s, James Lovelock introduced the Gaia hypothesis, which framed the planet as a complex system shaped by humanity’s interaction with the biosphere. Lovelock’s perspective does not ascribe will to Gaia; rather, it sees her as an evolutionary system encompassing all living organisms and their environments, such as oceans and the atmosphere. This concept diverges from the more homogenized view of the globe, which emphasizes resource control and exploitation. Bruno Latour (2017) builds upon this idea, arguing against the conflation of the Globe with the Planetary, emphasizing that the former represents an external frame that encompasses geopolitical entities. In the Nomos of the Earth framework, nature is treated merely as a resource for human exploitation, whereas the Gaia hypothesis encourages a broader perspective that acknowledges the active role of non-human components in the environment.

Latour’s interpretation expands the understanding of conflict beyond traditional definitions. He suggests that war involves a broader range of entities, not just humans, framing it as a conflict of all against all, where non-human actors, such as environmental factors, also play critical roles. This perspective, while transformative, does not entirely escape the antagonistic framework of the Nomos. Latour, alongside Lovelock, seeks to redefine sovereignty, distancing it from historical notions that justified imperialism. While he asserts that “geo” in contemporary contexts signifies a new Earth, the concept of Gaia risks reinforcing the idea of nature as an adversary, perpetuating a Darwinian perspective that overlooks the cooperative interactions crucial for evolutionary progress.

Chakrabarty’s recent work offers a distinct approach to the planetary by highlighting five characteristics that differentiate it from the global perspective. These features include the planet’s habitability, the inclusion of diverse life forms, the consideration of the planet’s history, and an openness to the various forms of life that inhabit it. This framework avoids the pitfalls of “green imperialism” by recognizing the importance of indigenous cosmogonies and the ancient consciousness of the planet, providing alternative insights into our planetary condition.

Chakrabarty’s perspective expands the dialogue about our relationship with the planet within a broader context, acknowledging that awareness of the planetary extends beyond contemporary discourse and into ancient traditions (Chakrabarty, 2023). While his framework offers valuable insights, it also reflects a modern awakening to our planetary reality, contrasting with long-standing indigenous and other philosophical traditions that have historically recognized the interconnectedness of all life.

In other words, the contemporary discourse surrounding the planetary challenges traditional views shaped by human-centered exploitation and highlights the need for a more inclusive understanding of our relationship with the Earth. By integrating diverse perspectives and acknowledging the agency of non-human actors, we can begin to move towards a more sustainable and equitable coexistence on our planet.

Spirit of the Earth: The Planet in Life Evolution

The concept of the Spirit of the Earth connects humanity to the planetary, representing an evolutionary process beyond mere geography or physicality. It is also referred to the noosphere, a term coined in the 1920s by geochemist Vladimir Vernadski and philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. The noosphere signifies an additional layer of thought and reflection added to the biosphere, with a profound impact on living beings. Vernadski characterized humanity as a “large-scale geological force” (Vernadski, 1945) long before the term Anthropocene emerged, highlighting a shift in understanding our role on Earth.

While Vernadski’s perspective on the noosphere is more secular and physical, Teilhard’s approach encompasses both the physical and metaphysical realms. He links the noosphere to progress, contrasting it with Bruno Latour’s views on the planetary. Scholars like Jonathan S. Blake and Nils Gilman explore these distinctions in their last book dedicated to the Planetary in 2024 but often overlook the deeper implications of Teilhard’s Spirit of the Earth (Teilhard de Chardin, [1946] 1959). Teilhard’s vision resonates with the notion that humanity is accountable for the future of the Earth. The Spirit of the Earth encompasses three fundamental aspects:

1. Unification of Human History: This aspect describes a historical convergence where national narratives merge into a singular history of humanity on Earth. Teilhard identifies two phases: the first is a geographical expansion from Africa to the rest of the world, while the second represents a compression of societies. This compression fosters a collective awareness of humanity, leading to both progress and tension. The era of globalization has led to a suffocating environment where individuals feel overwhelmed, resulting in rising nationalism and populism.

2. Link Between Personalization and Planetization: Teilhard emphasizes that the Spirit of the Earth reflects a rise in human reflexivity and self-expression. It suggests that individuals increasingly feel connected not only to their local communities but to the planet as a whole. This shift promotes a greater understanding of our shared existence, encouraging individuals to recognize their place within the larger human experience.

3. Moral Imagination Beyond Survival: The Spirit of the Earth seeks to transcend mere survival, aiming for a positive existence characterized by moral imagination. Teilhard asserts that humanity’s evolution arises from a tenacious will to live more rather than a desperate struggle for survival. This moral framework reshapes geopolitical understandings, calling for collaborative efforts to build a sustainable future instead of succumbing to conflict.

Although current global issues—like Russia’s aggression and the malaise of multilateralism—paint a pessimistic picture, they should not overshadow ongoing processes of cooperation and crisis management. Recent achievements, such as the treaty to preserve high seas, signify progress in global governance and resource management.

The Spirit of the Earth represents a revolution—both personal and psychic—where individuals are invited to recognize their identity as earthlings. This transition encourages a broader consciousness, where the survival of humanity and the Earth becomes paramount. In contrast to John Herz’s “planetary mind” concept, which focuses on strategic dimensions of international relations, the Spirit of the Earth emphasizes individual agency and collective evolution.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified introspection, prompting individuals to reconnect with their surroundings and each other. Initiatives like StayHomeSounds demonstrated how collective experiences during lockdowns can foster a deeper appreciation for our interconnectedness. However, disparities in socio-economic conditions must be acknowledged, as they influence the capacity for individuals to participate in this transformative process.

The personal revolution aligns with the concept of human security, which emphasizes individual safety and dignity beyond state-centric frameworks. While historical interpretations of human security have often been distorted by political agendas, a renewed focus on personal agency and solidarity is vital for fostering a more compassionate global society.

The movement toward a Spirit of the Earth must encompass an economic revolution, challenging existing capitalist models and exploring sustainable practices. The pandemic revealed a return to consumerism despite calls for environmental awareness. However, innovative practices like permaculture—which promotes harmony with nature—show potential for a sustainable future.

Yet, challenges arise as the concept of Homo planeticus emerges, suggesting a new type of humanity focused on progress. This evolution raises concerns about the potential for domination, drawing parallels to historical examples of oppressive ideologies. Protecting the Spirit of the Earth from exploitation necessitates embracing decolonial approaches and recognizing the diverse perspectives of indigenous communities as valuable contributions to global sustainability efforts.

Ultimately, the Spirit of the Earth extends beyond intellect, encompassing love as a vital force. For Teilhard, love fosters recognition and appreciation among individuals, emphasizing the importance of individuality within a collective context. Love is the binding force that transcends differences, enabling humanity to evolve beyond coercion and conflict. Acknowledging the presence of love invites reflection on the interplay between convergence and personalization. While excessive individualism and nationalism hinder cooperative efforts, love fosters a deeper connection to the planetary experience. Bauman’s assertion that humanity faces a critical juncture—where collaboration is essential for survival—resonates deeply in this context (Bauman 2017) but also recent research emphasizing the role of love in the understanding of IR, both in the West and in other non-Western traditions (Harnett, 2020 ; Harnett, 2024).

In conclusion, the Spirit of the Earth encapsulates a transformative vision for humanity, urging individuals to recognize their interconnectedness with each other and the planet. Embracing this spirit necessitates a moral and personal revolution, challenging socio-economic systems while prioritizing love and solidarity as foundational principles for navigating the complexities of the contemporary world. Only the Spirit of the Earth, can sustain a lasting evolution for humanity, directed toward a paradigm shift based on love, solidarity, and collective responsibility. The two first representations though useful in understanding International Relations, remain centered on rivalry and war, whether territorial or ecological, the Spirit of the Earth introduces a transformative dimension that could reorient International Relations toward true global cooperation and a renewed understanding of human security.

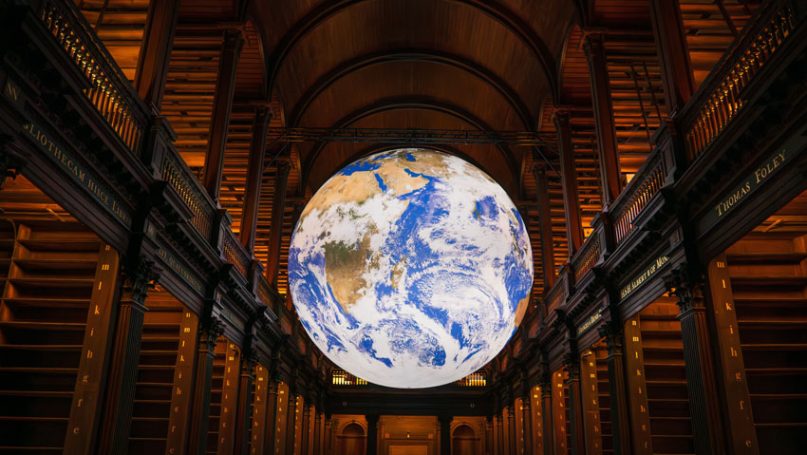

This “personal revolution” proposed by the Spirit of the Earth invites each individual to recognize their place within a shared world. This image calls for both spiritual and practical reflection on how to live in an interconnected world, potentially fostering a collective consciousness capable of meeting planetary challenges. In this light, the Spirit of the Earth embodies a humanistic and ecological approach to International Relations, where survival is no longer solely pursued through military power or domination but through a shared project of “building the Earth.” (Teilhard de Chardin, 1959).

References

Allison, G., 2017, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?. Scribe: Melbourne-London.

Arendt H., 2018, The Human Condition. Chicago: the Chicago University Press.

Bauman Z., 2017, Retrotopia. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Blake, J., and Gilman, N., 2024, Children of a Modest Star: Planetary Thinking for an Age of Crises. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Burke, A., Fishel, S., Mitchell, A., Dalby, S., & Levine, D. J., 2016, “Planet Politics: A Manifesto from the End of IR.” Millennium, 44(3): 499-523.

Chakrabarty D, 2023, One Planet, Many Worlds : the Climate Parallax. Bandeis University Press.

Hartnett, L., 2020, “Love as a Practice of Peace: The Political Theologies of Tolstoy, Gandhi and King.” In Theology and World Politics. International Political Theory, edited by Vassilios Paipais, 265-88. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hartnett, L., 2024, “How love orders: An engagement with the disciplinary of international relations. ” European Journal of International Relations 30(1): 203-26.

Herz, J. H., 1959, International Politics in the Atomic Age. New York: Columbia University Press.

Latour B., 2017, Facing Gaia. Eight lectures on the new climatic regime. Cambridge, Polity Press.

Rosa H., 2013, Social Acceleration. A New Theory of Modernity. New York : Columbia University Press.

Sprout H., and Sprout, M., 1971, Toward a Politics of the Planet Earth. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

Schmitt C., 2003, The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of Jus Publicum Europaeum, Telos Press Publishing.

Teilhard de Chardin, P., [1946] 1959, “La planétisation humaine.” In L’avenir de l’homme. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, 157-175. Paris: Seuil.

Teilhard de Chardin, P., 1959, “Building the Earth”, CrossCurrents. Fall 9(4): 315-330.

Vernadski, V., 1945, “The Biosphere and the Noosphere.” American Scientist, 33 (1) January: 1-12.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Geopolitics and John Dee

- Call of Duty and Our Geopolitical Reality

- Regional Neorealism: Rethinking Geography and Geopolitical Competition

- Everyone is Talking About It, but What is Geopolitics?

- Opinion – The Coming of Age of the European Union’s Indo-Pacific Strategy

- Plotting the Future of Popular Geopolitics: An Introduction