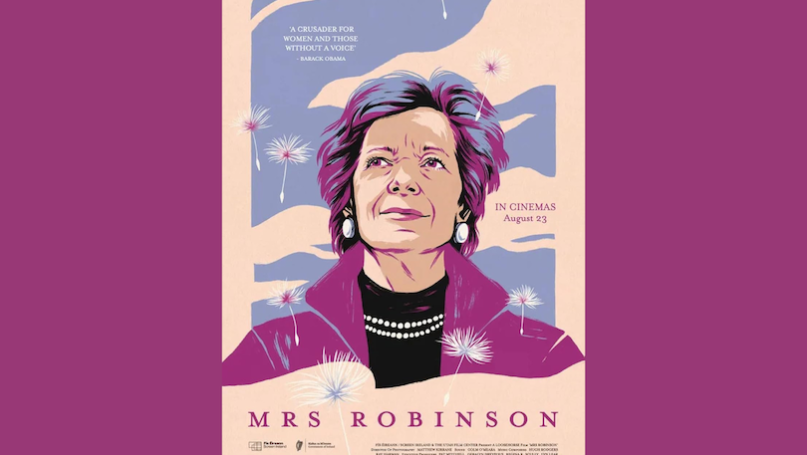

Mrs Robinson

Directed by Aoife Kelleher, 2024

Few countries are fortunate enough to possess a working statesperson who has been its President; head of one of the UN’s most politically sensitive agencies (Human Rights); chair of the UN Elders (a council formed to improve global governance) and whose “retirement” had been characterized by vigorous environmental and human rights activism. The life and international impact of Mary Robinson, the first female President of Ireland, have now been marked by this production which will intrigue IR students and instructors, and anyone interested in UN history and NGO activism.

Robinson retains a strong footprint in the formal processes of the UN system, and the wider phenomena of global environmentalism. Indeed, she was oftentimes criticized for awkwardly falling between those two contentious stools. This film tells her story “warts and all” and has been welcomed by Mary in her forthright admission, ‘I am glad my mistakes were covered’.

In contributing to the making of this movie, this writer would observe that Mrs Robinson was anxious to avoid reproducing a sanitized filmographic version of life or career. When people talk with nostalgia about her Presidency, they forget how many contentious decisions had to be made at that time. Women’s and civic rights had to be fought for. As for the UN, well that organisation is famous for opening the eyes of saints. She did not always get it right and never claimed to do so. But this filmographic evidence suggests that Robinson endeavoured to do what she believed was right, even when this was unpopular.

Structurally, the life of the subject gives resonance to the filmography. There are reels of family clips. The viewer might appear frustrated by the quickness of a plot which finds her one moment in family imbroglio about her marriage to historian Nick Robinson, and then speechmaking in the Senate. Ireland regards Mary Robinson as an effective and popular President, and for the most part the international community applaud what she achieved at the UN and since. This film was made with her full co-operation and there is a certain (perhaps unavoidable) tone of national homage. All such biographical films are by their nature, contextualized for a receiving audience. At times director, Aoife Kelleher, steps in as if to hold this self-celebration to account, and dissect some of the controversies Mary Robinson generated, along each stage of this eighty-year journey.

Mary Robinson was something of a lone jurist when she defended the illegal pro-contraception activities of Irish feminists, or controversially visited the north or met the late Queen Elizabeth II. She was not a universally popular UN leader and her 2001 World Conference Against Racism held in Durban, South Africa, was something of a political disaster. She never shied away from controversy and the film captures something of the “ups and downs” of a career spent in the eye of the camera.

Kelleher was able to speak frankly to Robinson and there are a few confessional notes where the listener will feel privileged to see how a powerful stateswoman has to personally battle against formidable global forces. Diplomatic life is not meant for those courting a popularity contest. We see a little of the personal effort needed to get decisions over the line, and maybe also of the privileges which go with high office. Her statements are characteristically authentic and genuinely emotive, but in this movie, she appears preponderantly as a leadership figure in the exclusive cabin of an aircraft or a posh car, while at the same time touring the world to prevent climate change. There is an inevitable eliteness about her life – Trinity, Senate, Harvard, Aras, Palais des Nations – state dinners, receptions, and attendants offering personal coiffure. More on the “personal Mary” would have been welcomed.

What about her greatest mistakes? Well, she does speak honestly about the dilemma she felt in stepping down as President to become UN Human Rights Commissioner. She suggests that running a UN agency is “not a task for the faint hearted, and at times UN politics would evaporate the patience of a saint”. She regrets the time stolen away from her family life, and the inevitable loneliness of a top international civil servant. She also readily touches on her personal involvement in the Dubai princess abduction case, and how she has sometimes “taken much on trust.” Mrs Robinson had described Princess Latifa as a “troubled young woman” after she met her at a lunch on invitation from Dubai’s royal family in 2018. Princess Latifa had attempted to flee the country earlier that year, and Mrs Robinson later said she had been “misled” in vouching for the princess’s safety.

RTÉ Entertainment recently asked if making the new film had provided closure for her on the different controversies she had endured in high office? Mrs Robinson replied: “Particularly with the presidency… the truth was, I was afraid that (UNSG) Kofi Annan wouldn’t wait for me… and I didn’t have any other option… I understood that it really was a mistake. I should have served the full term…” She also said that the film-makers were highly sensitive to the Princess Latifa controversy, which she conceded, made her look leaden-footed: “I actually encouraged its mention, as I wanted the mistake [of visiting] Princess Latifa (to be raised) in the film – I was very happy that Aoife was including it – because it was just a big mistake. And people make mistakes.”

Kelleher faces a hard task in trying to represent an inspirational story of a Ballina girl becoming a successful jurist, politician, President and UN supremo. It is certainly not a “rags to riches story” but at the same time, her meteoric career expressed a social fluidity Ireland had not previously encountered. Her Presidency and that of her immediate predecessor, Patrick Hillery, could not have been less alike. A politically outspoken lawyer and senator in her early career, her Presidential vote in 1990 was a bombshell to an Irish society which at the time had scarcely embraced societal change.

As UN High Commissioner she risked her job by controversially challenging the international perpetrators of human rights abuses, without fear or favour. No-one could accuse Robinson of bias when applying UN censure. This movie captures the decisiveness of a women from a small country which was traditionally deferential to the USA. However, Washinton was never spared when the High Commissioner turned to hard questions, and that created enemies on the Hill. She was especially vocal on capital punishment.

At 80 she remains Chair of The Elders; the independent group of global leaders (founded by Nelson Mandela) lobbying for peace, justice and human rights. She is also the principal advocate for Project Dandelion: a women-led climate justice campaign. Kelleher presents Robinson as a highly articulate commentator, and allows her to tell her own story. These words are heart-felt and at times filled with the bitter-pain of honesty. We could all learn something from the frank act of public reflection which is inherent in sharing a life in film.

So, while this movie may appear elitist, this reviewer would encourage students to look carefully at the side-action, not only in Ireland as she constructed her career, but the rocky journey any statesperson endures. So, we get flittering glimpses of conversations and quarrels sometimes even on camera. Neither election or street politics are pleasant sights, whether for a humble town Council or the lofty election of High Commissioner for Human Rights. The viewer may leave this movie with a little more respect for the trappings that go with bagging an office in Geneva’s Palais Wilson when one sees the dogfights Mary endured in the backroom corridors of power, whether those were in Dublin, Geneva or New York.

Speaking about why she decided to make a film about her life, Mrs Robinson admitted that she “actually wasn’t keen on the idea, at first”, until her late friend Bride Rosney persuaded her. “And now the film is dedicated to her,” said Mrs Robinson. She added, “It does give me a sense of closure too and might encourage the next generation, particularly women, to consider a career in politics… Going into politics is more difficult now – with social media… So you need a lot of courage…”

It may come as a surprise to those who view this film, that Mary Robinson confesses she was quite an anxious student and she urges that, “people should not let their shyness hold them back… I wanted to be able to speak – and I really had to work at it…” IR students will find this film a frank portrayal of the “ups and downs” of a life spent in the public limelight, and of obstacles encountered at the pinnacle of decision-making in a global organisation such as the UN.