On Thursday, 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine (Sheftalovich 2022). EU member states have supported Ukraine in its self-defence against Russia through direct financial and in-kind contributions, humanitarian and military (Trebesch et al. 2023). In a letter dated 24 May 2023, the Dutch Ministry of Defense informed the Dutch parliament of its intention to collaborate closely with Denmark, Belgium, and the UK to train Ukrainian fighter pilots following US approval (Ollongren 2023, 1–2). On 18 August 2023, the news broke that a coalition led by the Netherlands and Denmark had received US approval to provide F-16 fighter planes to Ukraine (Schaart 2023). This article is a foreign policy analysis of the decision by the Netherlands, along with Denmark, to form the F-16 coalition for Ukraine, training Ukrainian pilots and donating F-16 fighter jets. My hypothesis is that the Dutch decision to co-lead the fighter jet coalition for Ukraine was partly motivated by international status seeking. This article fills a research gap related to small-state prestige-seeking behaviour, where no case has been studied concerning donations. The paper also researches the coalition-building aspect of donations concerning status-seeking.

In the literature, a distinction is made between output and input in NATO burden-sharing (Ringsmose and Jakobsen 2017, 1–4). The training activities and military expenditures of the F-16 coalition are investments in a war in a third country. They would thus be considered output, in line with the tendency of small states to see their defence contributions as a fee to receive military protection from more prominent allies and to focus on output (Ringsmose 2010, 331–32). Highly related is the idea that small states may seek prestige and recognition when contributing military resources to NATO missions, expecting perks such as protection in return (Pedersen and Reykers 2020, 17).

This article shows that a prestige-seeking mechanism may have contributed to Denmark and the Netherlands deciding to set up and co-lead the F-16 coalition for Ukraine. Until now, no research on small-state prestige-seeking has emerged where the object of study is prestige-seeking through military donations rather than direct contributions. Besides, the case is worth studying, considering the involvement of large sums of taxpayers’ money.

Dutch politician Mark Rutte, then Dutch Prime Minister during the period studied and now the NATO Secretary General, may have also played a vital role in the decision-making. His visibility alongside Ukrainian President Zelensky, following the F-16 donations, helped him bolster his international profile for his nomination as NATO Secretary General. Thus, this research suggests that the position of NATO Secretary General may be awarded as a reward for “good behaviour” as viewed by the alliance patron.

Theory

The small-state status-seeking literature, centered around the NATO alliance, stems from the idea that a fear of being attacked or defeated in war is not enough to explain the behaviour demonstrated by small states in alliances (Pedersen and Reykers 2020, 17). Rationally and relying on threat perception only, states would maximise defence spending. Conversely, small states often limit spending while maximising capabilities for NATO out-of-area missions. This overperforming behaviour can be explained by the fact that gaining prestige and being seen as a good partner by the alliance patron yield rewards, such as protection (Pedersen and Reykers 2020, 17). Security is thus gained at a lower cost. Moreover, small states’ higher defence expenditure in percentage of GDP would lead to a low absolute increase in the alliance budget. Other rewards may also follow from being a good partner (Neumann and Carvalho 2015, 10–11 and 16–17; Pedersen and Reykers 2020, 17; Oma and Petersson 2019, 122). As Jakobsen, Ringsmose, and Saxi note (2018, 258),

small states are also concerned about their prestige and status. They perceive military contributions to US-led coalitions as obtaining prestige and good standing in Washington that they can convert into access, influence, or various forms of US support.

Further, a small state may contribute to military coalitions out of fear of abandonment (Oma and Petersson 2019, 107–8). This mechanism is demonstrated in the cases of Swedish and Norwegian military participation in the International Security Assistance Force led by NATO (Oma and Petersson 2019, 106).

The existing small-state status-seeking literature focuses on prestige-seeking through direct military participation in NATO missions. Prestige-seeking through military donations remains unexplored. This paper fills this research gap by assessing the case of the F-16 coalition for Ukraine, spearheaded by Denmark and the Netherlands, two small-state NATO allies. It researches the presence of a status-seeking mechanism through donations and coalition-building.

Following Russia’s unprovoked full-scale invasion of Ukraine, NATO allies, including the Netherlands, have emphasised that a Ukrainian victory over the Russian aggressor is also vital for the territorial defence of NATO (Raad Algemene Zaken and Raad Buitenlandse Zaken [General Affairs Council and Foreign Affairs Council] 2023, 32; Piri and Veldkamp 2023). The war is seen as a war for European values and against Russian imperial ambitions (Austin III and Milley 2023; Piri and Veldkamp 2023; Economides 2024). The Netherlands has decided to lead an F-16 Coalition in cooperation with Denmark, donating F-16 fighter planes to Ukraine and training Ukrainian fighter pilots (Schaart 2023).

The usefulness of F-16s for the Ukrainian army stems from various sources (Tannehill 2023). Most importantly, F-16s can be used as a mobile anti-air platform. Additionally, the F-16s can fire advanced weapon systems otherwise unavailable to Ukraine. Besides, F-16s and the training received by Ukrainian pilots will help Ukraine align its military with NATO and indicate that Ukraine may join NATO later (Starling, Mezey, and Ryan 2023). However, the F-16 will not win the war alone (Starling, Mezey, and Ryan 2023; Tannehill 2023). It will still have to operate far from the front line, limiting its ground support capabilities. Besides, Russian radars can detect the F-16 more easily than newer fighters like the F-35.

Despite the disadvantages, Ukraine’s allies assessed that the advantages of the F-16 for Ukraine merit forming the F-16 coalition and donating F-16 aircrafts (Dutch Government 2023). This warrants the central question of this paper: Why did the Netherlands decide to co-lead the F-16 coalition for Ukraine? I hypothesise that international status-seeking will have played a role. Of course, “prestige-seeking should only be regarded as one policy driver among others” (Jakobsen, Ringsmose, and Saxi 2018, 276), and traditional strategic considerations will have played a role.

Method and Case Selection

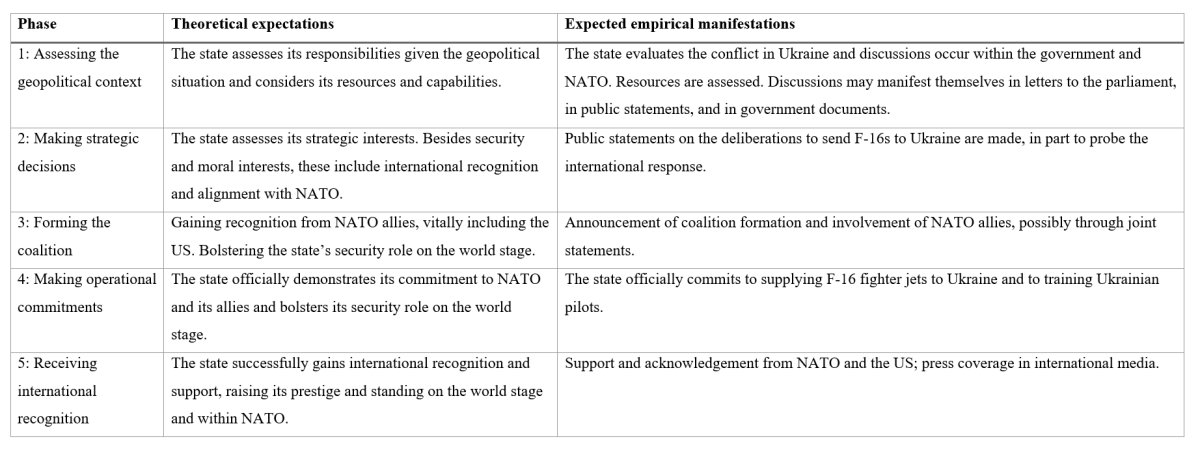

The analytical section uses process tracing (Beach and Pedersen 2019) to assess the likelihood of a specific mechanism’s presence in the Dutch decision-making around establishing the F-16 coalition for Ukraine. As such, the present section establishes a five-phase model of a hypothesised status-seeking mechanism in the Netherlands’ decision to co-lead the F-16 coalition for Ukraine. For each phase, the model predicts certain theoretical expectations and links those expectations to expected empirical manifestations. Said expected empirical manifestations then serve as a potent tool for the analysis in this essay, namely by providing clear indicators to test the presence of the status-seeking mechanism in my case. I will thus trace the Dutch decision-making process and test my model against evidence from primary and secondary sources.

As discussed in the theory section, emerging literature suggests that international status may be a vital factor in deciding upon military assistance or contributions in alliances. My case is relevant as it may contribute new insights into small-state behaviour concerning NATO burden sharing. Specifically, it could be a case in which prestige-seeking is involved, thus strengthening the literature on that mechanism. Besides, the case is essential as the decision to form the F-16 coalition for Ukraine has led several democratic countries to commit considerable resources. Additionally, by allowing F-16 fighter jets to be used in Ukraine’s defence against Russia, the NATO allies are taking increased risks both in terms of potential escalation of and involvement in the war as well as in terms of technology protection.

My aim is not to prove that a status- or prestige-related mechanism is in place but only to show that it is likely, given the empirical evidence. Besides, status-seeking is only one factor in deciding to aid Ukraine. Security concerns over Russian aggression and moral considerations over Ukraine’s legitimate right to self-defence will also have played a role, among other arguments. However, the choice to contribute with F-16s may have depended on considerations of prestige due to the high visibility of such contributions.

Public recognition benefits more than just the Netherlands and Denmark. An alliance’s strength depends on the allied states’ willingness to support each other. As such, public recognition of the alliance at work bolsters NATO’s deterrence strategy (Ringsmose 2010, 336). The US could have played a crucial role in shaping the fighter jet coalition, potentially even asking the Netherlands and Denmark to donate the planes in the first place.

Availability of primary sources

The case studied in this paper is highly contemporary, as the war in Ukraine is ongoing. Besides, the matters discussed touch on classified data. Moreover, the status-seeking behaviour that I expect to be present would be undermined if the status-seeking nature of the Dutch behaviour came to the fore explicitly. It is preferable to the Dutch government if it appears to be guided exclusively by moral reasons. The Dutch people and the international community would appreciate this moral stance. Furthermore, the Dutch taxpayer may be more easily convinced by rational, self-serving security considerations than by the Dutch status-seeking, even if other benefits are likely attached. Therefore, it is difficult to find any hard evidence that the Dutch government engages in such status-seeking behaviour and to schedule any interviews to help detail the decision-making process. Instead of such hard evidence, this essay relies on primary and secondary sources that indirectly imply or increase the likelihood of status-seeking behaviour, such as government statements and newspaper articles.

Prior expectations

Based on the above, I expect to find a fair amount of evidence of moral and geostrategic reasons playing a role in the Dutch decision to co-build the fighter jet coalition for Ukraine and donate planes. Conversely, prior expectations of evidence of status as a motivation are low. Following the concept of informal Bayesian reasoning (Beach and Pedersen 2019, 175), I will not quantify the prior expectations. However, informal Bayesian reasoning suggests that my relatively low prior expectations of finding evidence allow us to upgrade my confidence in larger steps than if prior expectations were high. Therefore, even if I cannot conclusively prove the presence of the status-seeking mechanism, I can highly increase my confidence in its presence by showing relatively little proof (Beach and Pedersen 2019, 175, 178, 182).

Analytical model

My model, outlined in Table 1, expects public announcements across five steps to maximise coverage and prestige gain. This could be coupled with statements from key allies, such as the United States, approving of the Dutch and Danish commitments. Besides, President Zelensky’s willingness to attend press conferences while his country is at war would indicate that prestige and recognition play a role in countries’ decisions to support their allies.

An invitation by the US to Denmark and the Netherlands, asking them to take the lead role in the fighter jet coalition, would be expected. Such an invitation would align with the recent literature, which suggests that the US often invites NATO members to contribute in a specific manner (Pedersen and Reykers 2023). It would fit under phase three. In phase 5, next to public statements supporting and acknowledging the Dutch contributions, there may be other tangible rewards (Neumann and Carvalho 2015, 16; Pedersen and Reykers 2020, 17; Oma and Petersson 2019, 122).

Analysis

Here, I will test the model against empirical data. If the expected empirical manifestations show, this will upgrade my confidence in my thesis that the F-16 coalition for Ukraine was partly formed for status-seeking reasons. If the mechanism described is not clearly present, this may indicate a lack of evidence in the public domain on the one hand or the absence of the mechanism altogether on the other.

The analysis covers the stages in Table 1: the presumed prestige-seeking process in forming the F-16 coalition for Ukraine. It presents relevant empirical evidence from primary and secondary sources for each phase. Then, it concludes the presence or absence of empirical evidence for the respective phases and assesses the quality of the evidence.

Phase 1: Assessing the geopolitical context

In the first phase, my model expects that the state assesses its responsibilities given the geopolitical situation and considers its resources and capabilities. On 19 January 2023, nearly a year after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a commission debate took place at the Commissions for Foreign Affairs and European Affairs, discussing with Minister Hoekstra of Foreign Affairs. Minister Hoekstra emphasised the continued need for support for Ukraine in the debate, saying:

As far as I am concerned, there is, therefore, no other choice for the Netherlands but to continue supporting Ukraine for peace and security there, as well as for peace and security more broadly in Europe. This also means that the cabinet will continue to assess what is needed (Raad Algemene Zaken and Raad Buitenlandse Zaken 2023, 28).

On the impact of weapon donations to Ukraine for the readiness of the Dutch army, Hoekstra states “that does not alter the fact that it is my conviction that, all things considered, this is indeed sensible, especially since Ukraine is ultimately fighting against the country that could pose the very first threat to NATO” (Raad Algemene Zaken and Raad Buitenlandse Zaken 2023, 32). Minister Hoekstra, speaking on behalf of the Dutch government, assesses the threat to Ukraine not just as an attack on Ukraine but also of strategic relevance to the Netherlands and NATO.

The Dutch parliament agrees with the government’s assessment that support for Ukraine is necessary. This is shown, for example, by a motion submitted by the members of parliament Piri and Veldkamp (Piri and Veldkamp 2023) on 12 December 2023. The motion mentions the importance that Ukraine can keep defending itself against Russian aggression, noting that Russian aggression also threatens the rest of Europe, including the Netherlands. It continues to support Ukraine’s right to self-defence. Furthermore, it states that the Netherlands should keep its leading role in delivering financial, humanitarian, economic, military, and diplomatic support for Ukraine. The motion was adopted with 97/150 votes in favour.

A later motion of 20 April 2023, submitted by the members Brekelmans and Sjoerdsma (2023), conveys an increased sense of urgency in supporting Ukraine in the Dutch parliament. It employs a stronger wording than Piri and Veldkamp’s earlier motion, noting that the support thus far has been reactive. It states that the Ukrainian army should, in due time, approach NATO standards, aiding Ukraine in reconquering its lost territories. It recalls that the Dutch parliament has expressed before that there may be no taboo on the delivery of weapon systems of any sort to Ukraine. Thus, the motion states that the government should start training Ukrainian military personnel in using advanced Western weaponry for the short and long-range as soon as possible to allow for a swift deployment of said weapon systems should their delivery occur. The motion was adopted with a more significant majority than that of Piri and Veldkamp, with 110/150 votes in favour.

Thus, the state has gone through a series of deliberations before deciding whether and how to support Ukraine. The government and parliament are willing to help Ukraine win the war against Russia. This support stems from various factors, both geopolitical and regarding the moral duty to support Ukraine. It may include far-reaching measures, including military donations and training.

Phase 2: Making strategic decisions

In Phase Two, my model expects that the state assesses its strategic interests. Besides security and moral interests, these include international recognition and alignment with NATO. Here, I present empirical evidence that increases my confidence that the Netherlands have considered, among other factors, international prestige in their early deliberations to form the F-16 coalition for Ukraine. This manifests in press statements about forming the F-16 coalition, which could serve to gauge public opinion and plant the seed for further national and international debate. It also displays an initial, cautious commitment.

When deciding what type of support to deliver to Ukraine, the Dutch government has coordinated with its allies and Ukraine. Often, weapons donations were a direct answer to specific Ukrainian requests. When the Netherlands decided to collaborate with Germany and the United States to deliver Patriot air-defence systems, for example, it did so in response to “[t]he request that Kuleba has made to me, that Zelensky has made to Rutte, a request that has been made very broadly, ‘please also help us to protect our people by providing us with defence capabilities’”, said Minister Hoekstra of Foreign Affairs (Raad Algemene Zaken and Raad Buitenlandse Zaken 2023, 29). Regarding the F-16 coalition, Ukraine voiced the desire to receive modern Western fighter jets. During a debate of the standing committee on Defense of the Dutch parliament and the delegation to the NATO assembly, in discussion with Defence Minister Ollongren on 9 February 2023 (De Lange 2023, 34, 36, 37), the minister emphasised that she understood the formal Ukrainian request for F-16 fighter planes. However, she clarified that the path towards potential delivery of F-16 weapon systems would be long as many factors must be put in place first. These included proper training of Ukrainian military personnel and preparation of the infrastructure and logistics needed to operate the aircraft from Ukrainian bases. A commission member, Sjoerdsma, insisted on further statements from the minister; the minister clarified that there were ongoing talks between the Dutch government and its allies to explore the possibilities of fulfilling the Ukrainian request. Moreover, she agreed with Sjoerdsma that it could be a logical step to start training Ukrainian pilots on a relatively short timeline. The minister added that, besides the current relevance of F-16s for Ukraine,

we also need to look at the future. Ukraine will have to replace all its equipment with equipment it can access in the future. This means that everything that is now old, Russian equipment, needs to be replaced with equipment from Europe, America, and other parts of the world. In this context, it is appropriate to consider, for example, F-16s for the Air Force (De Lange 2023, 37).

In other words, there was governmental and parliamentary support for the idea of the F-16 coalition for Ukraine. Moreover, the Netherlands assessed that the international community, the United States, and its NATO allies would support and applaud the fulfilment of Ukrainian requests for help.

Phase 3: Forming the coalition

In the third phase, my model expects that the Netherlands aims to gain recognition from NATO allies, vitally including the US and to bolster the state’s security role on the world stage. In this stage, the Netherlands makes an initial announcement that formalises the definitive intention to set up an F-16 coalition for Ukraine through joint statements with initial international partners. Notably, the Netherlands’ allies express their support for the initiative.

In a commission debate of 19 January 2023 of the Commissions for Foreign Affairs and European Affairs, discussing with Minister Hoekstra of Foreign Affairs, Minister Hoekstra pointed at the “connecting role” the Netherlands tries to play in collaborating with its allies (Raad Algemene Zaken and Raad Buitenlandse Zaken 2023, 31). In particular, he notes that the Dutch government enjoys tremendous support from parliament and society, which is not true for all allies. Thus, the Netherlands can lead the way, allowing other countries to follow in its footsteps more quickly, assuming they would not break a potential red line. Additionally, Hoekstra says that acting together makes for a more potent political signal. The implication that the Netherlands leads the way and facilitates its allies working together fits my model’s expectations that the Netherlands tries to bolster its security role on the world stage. In the same report, Minister Hoekstra pointed out that the Netherlands has also taken on a lead role in justice (Raad Algemene Zaken and Raad Buitenlandse Zaken 2023, 35). This role fits the Netherlands as it already hosts various international courts. Hoekstra bringing up these lead roles for the Netherlands shows that Dutch politicians are aware that the Netherlands plays an influential role on the world stage and display an appreciation for this situation. This signals that the Netherlands actively uses its coalition-building role around the donations in pursuit of status.

More closely related to this case study of the F-16 coalition, the Dutch government reiterated, in written consultations with the standing commission for Foreign Affairs of the Dutch parliament on 11 May 2023 (Prenger 2023, 8–9), that F-16 deliveries for Ukraine are not a taboo for the Dutch government. Besides, the government emphasised that “the cabinet is actively working to build international coalitions and to make such support possible” and “the cabinet is working intensively and closely with partners on this issue” (Prenger 2023, 9).

As Pedersen and Reykers have theorised (Pedersen and Reykers 2023, 5–8), small-state status-seeking behaviour often involves an invitation to contribute from the alliance patron. In this case, that would mean an invitation from the US to the Dutch and Danish governments to collectively rally the West behind forming an F-16 alliance. Indeed, a statement on the official website of the Danish Ministry of Defense suggests the presence of such an invitation. In the statement, the Ministry cites Minister of Defense Troels Lund Poulsen as saying:

The fact that the United States is reaching out to Denmark and our colleagues in the Netherlands as their first choice, asking us to play a larger role, is something we can be proud of. It is a recognition of the task, solved by the Danish Defense, swiftly establishing a Ukrainian F-16 fighter plane capacity.

The statement is about the Netherlands and Denmark co-leading “a new air force coalition”, which, according to the statement, “will support Ukraine in creating a complete F-16 fighter aircraft capacity” (Danish Ministry of Defense 2023).

The idea to co-lead the F-16 coalition may thus not have emerged solely on the part of Denmark and the Netherlands but in close collaboration with the US. The US may even have asked Denmark and the Netherlands for contributions of this kind. Notably, the Danish Ministry of Defense is the sole source encountered during the research for this paper that mentions the existence of such an invitation. Still, given that the existing literature on status-seeking gives considerable attention to the invitation mechanism, the document is remarkable. The invitation is no definitive proof of status-seeking behaviour by the Netherlands, but it increases my confidence that status-seeking may play a role. Besides, it hints that coalition-building around donations can lead to international recognition and status.

Considering the government’s deliberations and the potential US invitation, Phase 3 is present. The Netherlands has tried to bolster its security role by taking the lead in various aspects, such as justice and the fighter jet coalition. In so doing, Minister Hoekstra points out, they work closely with their allies. Besides, the Netherlands got US recognition and support by responding to their invitation to form a coalition with Denmark.

Phase 4: making operational commitments

Stage 4 expects the Netherlands to officially demonstrate its commitment to NATO and its allies and bolster its security role on the world stage. Official commitments are made by informing the parliament and allies and by informing the public through press moments or public statements. The Dutch commitment to initiating the F-16 coalition for Ukraine is formalised.

The Dutch government informed the Dutch parliament of its commitment to coordinate the F-16 training for Ukraine via a letter sent on the 14th of June, 2023 (Ollongren 2023, 1–2). This letter informed the Dutch parliament that

the Netherlands and Denmark, with full support from the US, have taken the lead in coordinating European efforts in this area. In close consultation with Belgium, Norway, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, and the industry, work is being done on the details of the training modalities.

Thus, the Netherlands had officially committed internally to the diplomatic efforts of setting up the F-16 coalition for Ukraine in collaboration with Denmark and working to rally its allies together.

Following the official notice to parliament, on 11 July 2023, the Dutch government released a diplomatic statement formalising its commitment to training Ukrainian F-16 fighter pilots in a joint coalition (Dutch Government 2023). The statement details that the coalition will train “relevant Ukrainian pilots, technicians and support staff” The goal is for the Ukrainian Air Force to be able to “operate, service and maintain F-16 fighter aircraft” where basic capabilities are concerned. Further, the statement names Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, and the United Kingdom as partners in the coalition. It finally mentions that the initial focus is on training, as outlined above, but that the partnership will consider “other lines of effort” in due time to allow the Ukrainian Air Force to develop “a fully functional F-16 capability” (Dutch Government 2023, 2). This hints at a long-term commitment to training the Ukrainian Air Force and the possibility of delivering modern fighter jets and related arms.

The diplomatic statement constitutes the public commitment part of Phase 4. The internal and public parts of the evidence expected in this phase are present. I conclude that the Netherlands officially committed to taking the co-lead in the fighter jet coalition for Ukraine, and Phase 4 occurs.

Phase 5: Receiving international recognition

Phase 5 is about the Netherlands successfully gaining international recognition and support, raising its prestige, and standing on the world stage and within NATO. In this phase, empirical evidence includes press statements, international media coverage and, importantly, statements of support and thanks from NATO, the US, and Ukraine. This phase’s timeline partly overlaps with phases 3 and 4; these phases are thus not strictly separated chronologically, not least because the Netherlands already got international recognition (Phase 5) from events before the official commitment (Phase 4). Still, the order makes sense as the central part of the events in Phase 5 occur after those in Phases 3 and 4. Furthermore, the analysis of Phase 5 includes several sub-phases because various events generated international recognition for the Netherlands.

As it is outside the scope of this thesis to analyse all media coverage, I collected the primary search results related to each sub-phase from the BBC, CNN, Politico, Politico Europe, The Economist, and The New York Times. These six significant and respected news outlets should offer a varied and comprehensive perspective from different viewpoints in the West. Besides, I examined public statements from the US, Ukraine, and NATO, giving recognition to the Netherlands. Data collection for this paper ended in April 2024.

Phase 5.1: US to allow training of Ukrainian pilots on F-16 planes; Netherlands take lead role

Phase 5.1 concerns press statements that primarily relate to the US decision to allow the export of F-16 planes to Ukraine when the time is ripe. In this decision on 19 May 2023, the US clarified that Western allies would be allowed to supply Ukraine with F-16 planes for training purposes. Additionally, they could commence training as soon as they were ready and made the relevant requests. While these statements are not focused on the Netherlands, they do refer to the Netherlands as one of the countries that pushed for the US to allow the F-16 to be used by Ukraine. This is, thus, from the perspective of Ukraine, NATO and the US, an acknowledgement that the Netherlands is correct in its assessment that F-16s should be delivered to Ukraine.

In this phase, I found relevant articles from the BBC (Beale and Gregory 2023), CNN (Kent, Kesaieva, and Lendon 2023), Politico (Seligman 2023a), Politico Europe (Bayer, Gallardo, and Seligman 2023) and The New York Times (Jakes and Schmitt 2023). The Netherlands was mentioned a fair number of times, although it was never the sole focus of an article. Still, considering that this moment was about a US decision, it is a free public relations moment for the Netherlands.

Concerning government statements made, even though the press articles mention the Netherlands, both the official US Department of Defense statement (Lopez 2023) and a Twitter statement by President Zelensky (Zelensky 2023a) are solely about the US. This makes sense, considering the moment represents a US decision, not an official commitment from the Netherlands. There was, however, a news conference following a meeting of the Ukraine Defense Contact Group (Austin III and Milley 2023) in which US Secretary of Defense LLoyd Austin explicitly mentions Denmark and the Netherlands as taking the lead in the committee discussing the F-16 donations. Besides. Austin said “I especially want to thank Denmark and the Netherlands, which have decided to lead a European coalition in providing F-16 training for Ukrainian forces”, thus explicitly thanking the Netherlands for their coalition-building efforts in Europe. As such, the Netherlands got recognition from the US, a critical patron of NATO.

Phase 5.1 is thus an initial moment of international recognition. On the one hand, the Netherlands gained free publicity in the international press. The CNN article explicitly mentions the UK and the Netherlands in the title of its article, mentioning that these countries are “working to procure F-16 fighters for Ukraine” (Kent, Kesaieva, and Lendon 2023). The Politico Europe article names the Netherlands as one of “the leading contenders to donate the American-developed warplanes” (Bayer, Gallardo, and Seligman 2023). Politico quotes the Dutch Minister of Defense, Kasja Ollongren (albeit misspelt “Ollengren”), who tweeted, “we stand ready to support Ukraine on this” (Seligman 2023a). On the other hand, the Netherlands gained explicit international recognition from the US, their crucial transatlantic partner and patron of the NATO alliance. The Netherlands was thus recognised as a relevant actor on the global stage and an essential contributor to Ukrainian self-defence thanks to its coalition-building around the F-16 donations.

Phase 5.2: Final US approval on training; US will allow donations of F-16 fighter jets

In Phase 5.2, the Western allies had made their formal request to be allowed to begin the training of Ukrainian fighter pilots. The phase was constituted when the US approved this request on 18 August 2023. This led to a new wave of international press articles, such as the five I found by the BBC (Lukiv 2023), CNN (Liebermann and Bertrand 2023), Politico (Seligman 2023b), Politico Europe (Schaart 2023), and The New York Times (Schmitt, Ismay, and McCarthy 2023). This time, some articles were highly explicit in reporting about the Netherlands.

The Politico Europe article is the most elaborate about the Netherlands. Its title is “Netherlands, Denmark confirm US has approved sending Ukraine F-16 jets”, thus focusing on the agency of the two small states that chose to co-lead the F-16 alliance and their request rather than on the US approval itself. The article calls the Netherlands and Denmark the coalition’s leaders and cites three Dutch government officials: Prime Minister Mark Rutte, Defense Minister Kasja Ollongren, and Foreign Minister Wopke Hoekstra. In their quotes, they emphasise the role of the Netherlands in the coalition-building process and hint at further steps such as furthering the debate, beginning pilot training, and potentially donating F-16 planes to Ukraine.

All other articles also explicitly mention the Netherlands, often concerning the F-16 coalition. Some articles, such as CNN’s, focus more on Denmark, as that state formally requested the US. Others, such as the BBC article, offer a balanced view that includes quotes from Dutch, Danish, and Ukrainian government officials and an analysis of the potential impact of F-16 planes on the war.

Where official statements are concerned, both the US and Ukraine held out on releasing anything in Phase 5.2. This is potentially due to what was in the pipeline for 5.3, which followed just days later. Therefore, Phase 5.2 can be seen as a bonus. International press audiences were reminded of the role of the Netherlands regarding the F-16 coalition, but explicit recognition would follow some days later.

Phase 5.3: The Netherlands commits to donating F-16 fighter jets

Phase 5.3 follows briefly after Phase 5.2, namely on 20 August 2023. It concerns the Netherlands committing publicly to donating F-16 fighter jets to Ukraine. This led to a new wave of international press coverage just days after the previous one, and the Netherlands received international recognition from both the US and Ukraine.

I found articles on CNN (Brown and Kesaieva 2023), Politico Europe (Roussi 2023), The Economist (The Economist 2023), and The New York Times (Mpoke Bigg and Shankar 2023). Overall, they are often neutral in sentiment. They tend to address the US’s reluctance and discuss the potential gains and limitations that Ukraine should expect. Nonetheless, this wave of press coverage was likely the most positive about the Netherlands. For example, the articles contain thankful quotes from Zelensky, and some articles go out of their way to praise the Netherlands. CNN remarks that “[t]he Netherlands, a NATO member, has been a strong ally to Ukraine since well before Russia’s full-scale invasion began in February 2022” (Brown and Kesaieva 2023). The opening paragraph of the NYT article is “[t]he Netherlands and Denmark said Sunday that they would donate F-16 fighter jets to Ukraine—the first countries to do so in what President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine said was a breakthrough in his nation’s quest to acquire the aircraft considered imperative in the war against Russia” (Mpoke Bigg and Shankar 2023), thus starting by putting the Netherlands in a positive light.

Regarding statements from government officials, both the US and Ukraine praised the Netherlands for committing to donate F-16 aircraft to Ukraine. On 22 August 2023, the Pentagon’s Press Secretary, Brigadier General Pat Ryder, held a press conference (Ryder 2023). During the event, he expressed that the US “[is] very grateful to our European allies, Denmark and the Netherlands in particular, for leading this effort.” Later, during the same conference, he states that “Denmark and the Netherlands kick off this program”. Both statements acknowledge the Dutch leadership role in the F-16 coalition, and the US explicitly thank the Netherlands, a show of appreciation that hints at status elevation for the latter. Two days later, on 24 August 2023, the US Department of Defense released a blog post reiterating US support for the F-16 coalition and announced that the US are willing to assist in training Ukrainian pilots (Clark 2023). The blog post also repeats that the Netherlands and Denmark co-lead the coalition. It cites Ryder stating, “[t]he training provided by the United States will complement the F-16 pilot and maintenance training that’s already underway in Europe and further deepens our support of the F-16 training coalition led by Denmark and the Netherlands”, and acknowledges that the US will fill the gaps in the training capacity of the European allies rather than lead the effort.

On the Ukrainian side, President Zelensky sent three tweets thanking the Netherlands on 20 August 2023. The first tweet (Zelensky 2023b) speaks of “another step to strengthen Ukraine’s air shield. F-16s”. It mentions that as soon as the required training is done, the Netherlands will donate F-16 aircraft to Ukraine. It ends with “Thank you, Netherlands!” After the first tweet, the second tweet of the day (Zelensky 2023d) reflects on “a powerful and very fruitful day”. Zelensky thanks Mark Rutte, his team, and the Dutch people for their commitment to donating F-16 fighter jets. In this case, the tweet also thanks Denmark and the US for their contributions. Lastly, the third tweet of the day (Zelensky 2023c) features a video of the press moments in the Netherlands and Denmark. The tweet includes “I thank you once again, dear @MinPres Mark, @Statsmin Mette, your teams, and the peoples of the Netherlands and Denmark”. In the tweet and the video, Zelensky is grateful for the jets and emphasises their importance to the Ukrainian army.

The international coverage from the Dutch commitment to donating F-16 aircraft is positive. Moreover, the Netherlands gained explicit recognition from the US, the principal patron of NATO, and Ukraine, the receiving country. The coordinated (Threels 2023) press conferences by the Dutch and Danish governments successfully solicited extensive positive tweeting by President Zelensky, including a video of his visits to the Netherlands and Denmark. The US thanked the Netherlands and Denmark in two press moments. This extensive coverage strongly indicates the gains in international recognition and status for the Netherlands resulting from their coalition-building efforts and donations.

Phase 5.4: The Netherlands opens a new training centre in Romania

In this phase, I discuss the response to the Netherlands opening a new training centre for fighter pilots in Romania on 13 November 2023, where Romanian and Ukrainian pilots will be trained. In terms of coverage in the international media, this event fell short of creating a buzz. Only Politico Europe reported on the opening of the training centre (Kayali 2023). While the Politico article discusses the Dutch role in inaugurating the training centre and delivering a large part of the required F-16 planes, it is not overly optimistic, and the reporting is factual.

President Zelensky (Zelensky 2023e), NATO’s Air Command (NATO Air Command 2023), the Ukrainian Air Force (Ukrainian Air Force 2023) and the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense (Ukrainian Ministry of Defense 2023a) tweeted to celebrate the opening of the training centre. All four explicitly mentioned the Dutch contribution to the training centre, and both Zelensky and the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense expressed their gratitude.

Even though international press coverage was low, the Netherlands managed to gain international recognition from NATO. This undoubtedly positively affects the increase or maintenance of the Netherlands’ status as a good NATO member.

Phase 5.5: The Netherlands announces preparation for delivery of an initial 18 F-16s

On 22 December 2023, the Dutch Ministry of Defense announced it would start preparing 18 F-16 fighter jets for delivery to Ukraine (Dutch Ministry of Defense 2023). Phase 5.5 further shows that the enthusiasm for reporting on the F-16 coalition has, for the moment, been watered down. Of the outlets I selected for my analysis, only the New York Times reported on the announcement (Méheut 2023) and only did so in the margins of an article on Russia making small gains in its illegal war against Ukraine. In terms of governments, President Zelensky (Zelensky 2023f) tweeted that he had called Mark Rutte “to thank the Dutch government for its decision to start preparing the initial 18 F-16 jets for their delivery to Ukraine”, and the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense likewise thanked the Dutch Ministry of Defense for “such an important decision” (Ukrainian Ministry of Defense 2023b).

The limited enthusiasm likely stems from many factors, including the bad news from the front at the time (Méheut 2023) and the announcement being minor compared to earlier announcements. This phase contributes little to my confidence that status-seeking plays a role in the present case.

Phase 5.6: The Netherlands earmarks six more F-16 planes for donation to Ukraine

Phase 5.6 discusses the extension of the Dutch commitment to delivering F-16s to Ukraine. Specifically, on 5 February 2024, the Netherlands announced that six F-16 planes that were destined to be sold to the firm Draken International would no longer be sold. Instead, they would be added to the 18 F-16s already destined for delivery to Ukraine (Dutch Ministry of Defense 2024).

Phase 5.5, about the preparation for delivery to Ukraine of 18 F-16 fighter jets for delivery to Ukraine, failed to generate much impact. Likewise, phase 5.6 hardly generated any reporting. This time, only Politico Europe wrote an article on the pledge (Posaner 2024), with Politico linking to that article in its National Security Daily section (Ward and Berg 2024). Regarding government responses, only the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense (Ukrainian Ministry of Defense 2024) and the Ukrainian Air Force (Ukrainian Air Force 2024) expressed their gratitude this time. The Ukrainian Ministry of Defense tweet featured a cool image and was quite extensive, stating that they “are grateful to our Dutch partners for their unwavering support”. The tweet by the Ukrainian Air Force was much shorter but said “Nederland bedankt”, Dutch for “Thanks, Netherlands!”

Like Phases 5.4 and 5.5, this phase contributes little to my overall confidence in the mechanism. Again, it does not contradict my hypothesis, either. Other sections show that the Netherlands gained significant international status.

Phase 5.7: Mark Rutte’s career

The literature on small-state status-seeking primarily revolves around the Netherlands, Norway, and Denmark (Ringsmose 2010; Ringsmose and Rynning 2009; Jakobsen, Ringsmose, and Saxi 2018; Pedersen and Reykers 2020; Pedersen and Reykers 2023). My theory section shows that it is broadly theorised that the patron of the alliance rewards “good allies” in various manners. The US, having the power to name the next person to hold the vital post of Secretary General, may thus consider the status of countries such as the Netherlands, Norway, and Denmark as a “good ally” in the naming process. After all, “the self-interest of diplomatic elites may account for some of the status fixation—as higher status gives access to hitherto closed clubs” (Neumann and Carvalho 2015, 16). Looking into the past NATO Secretary Generals reveals that they were indeed a Dutchman (Jaap de Hoop Scheffer), a Dane (Anders Fogh Rasmussen) and a Norwegian (Jens Stoltenberg).

To place this in the context of the Netherlands donating the better part of its fleet of F-16 aeroplanes, it is crucial to consider the well-acknowledged fact that Mark Rutte was recently appointed NATO Secretary General (NATO 2024), with NATO’s web page stating that Rutte “is a committed European and transatlanticist and was instrumental in bolstering his country’s role at the heart of NATO”. Moreover, reports Derix (2024) in NRC, the reputable Dutch news outlet, “[a]ccording to officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the motives of the Netherlands are not always pure, and the career of Prime Minister Rutte plays a significant role in the background”. Furthermore, the paper quoted Dutch civil servants at the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, stating, “[a]t the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, every effort is being made for Rutte’s NATO position”.

The case is advanced by a tweet from Zelensky (2024), which explicitly expresses gratitude towards Mark Rutte for a significant bilateral security agreement between Ukraine and the Netherlands rather than thanking the country and its people. Additionally, the idea that the donation performance of the Netherlands might be linked to Mark Rutte’s career is implied by the Kyiv Independent, which published an article that day reporting on the agreement (Hodunova 2024). Though this would seem irrelevant to the discussion of a deal between the two governments, the paper dedicates an entire section to reporting on Mark Rutte and mentions that he is the likely candidate for NATO’s top role:

Rutte is reportedly the leading contender to become the next NATO Secretary General when Jens Stoltenberg’s mandate ends on Oct. 1, after ten years in the role. Under Rutte, the Netherlands has proactively supported Ukraine by spearheading the fighter jet coalition and pledging to deliver 24 F-16 jets to Ukraine. Rutte told journalists on Feb. 26 that the Netherlands will provide 100 million euros ($108.5 million) in aid to support Czechia’s plan to procure hundreds of thousands of ammunition rounds for Ukraine from outside the EU (Hodunova 2024).

Although none of this constitutes definitive proof that the Netherlands engages in status-seeking behaviour when donating F-16 jets to Ukraine, it does increase my confidence that it may play a role. After all, Rutte positioned himself as a capable coalition-builder, rallying partners around the fighter jet coalition. Similarly, the fact that the next Secretary General of NATO will likely be Dutch would increase my confidence in status-seeking as a compelling explanation for small-state behaviour in defense-related foreign policymaking. Lastly, it is a remarkable and sensible idea that the high-profile spot of the NATO Secretary General could serve as an essential reward for small states that prove themselves as “good allies”.

Findings from the process tracing

Summary of Phases 1-5

Phase 1, “Assessing the geopolitical context”, saw the Dutch government assess the situation. The government decided it needed to support Ukraine out of a moral obligation and because it would help NATO and Europe safeguard their territories.

Phase 2, “Making strategic decisions”, encapsulated the Dutch decision on the support it would give Ukraine. In this phase, the Netherlands considered delivering F-16 fighter jets to Ukraine.

Phase 3 shows how the Dutch government started considering taking on the lead role in setting up the F-16 coalition for Ukraine. It also discusses how the Netherlands is familiar with such a role, for example, concerning justice for Ukraine. Importantly, it also brings forward a document from the Danish Ministry of Defense (Danish Ministry of Defense 2023) that signals that the US may have invited the Danish and Dutch governments to form Ukraine’s international fighter jet coalition. This would align with the theory put forward by Pedersen and Reykers (Pedersen and Reykers 2020; Pedersen and Reykers 2023) that alliance contributions are often based on an “invitation game” mechanism, where the alliance patron invites governments of small states to make certain decisions.

In Phase 4, the Dutch government makes operational commitments and decides to begin training Ukrainian pilots. The government has also committed to leading the F-16 coalition for Ukraine.

Phases 5.1 through 5.6 have all shown that different stages of commitment to the donation of F-16 fighter jets elicited different levels of international response. Some phases elicited very little international recognition, while others more than made up for this. In Phase 5.1, the Netherlands took on its co-lead role in the F-16 coalition; Phase 5.3 saw the Netherlands commit to donating F-16 planes to Ukraine; and in Phase 5.4, the Netherlands opened a new training centre for fighter pilots in Romania. All three phases led to explicit recognition from the US or NATO. The Netherlands will likely receive international coverage and recognition again as soon as the first jets are successfully deployed on the battlefield.

Phase 5.7 makes the case that Rutte’s appointment to the role of NATO Secretary General could partly result from the Dutch status-seeking efforts. Interesting parallels exist between the Dutch, Danish and Norwegian policies towards NATO, particularly regarding status-seeking within the alliance. Thus, as the position of Secretary General appears to rotate between these countries, the top spot may be allocated partly as a reward for this “good behaviour”. Such a reward would fit well with the literature (Neumann and Carvalho 2015, 16), thus strengthening my confidence in the mechanism taking place.

I can confidently conclude that the Netherlands has successfully received international recognition for its donations and coalition-building efforts. Crucially, Phase 5.3 saw many news articles that were very positive about the Netherlands and recognition from the US on multiple occasions. The Netherlands and Denmark coordinated their press events around this phase (Threels 2023), both attended by President Zelensky, who posed to take selfies with the F-16 planes and the leaders of the Netherlands and Denmark. This displays that the Netherlands and Denmark were interested in the status gain they stood to earn, even leading them to invest extra resources in receiving it. The US played along, thanking the Netherlands at various press moments. President Zelensky travelled to attend press conferences while his country was at war, acknowledging the importance of international status.

Presence of the status-seeking process

From the above analysis and summary, the mechanism described in my model section appears present in the Dutch decision to provide Ukraine with F-16 fighter jets. The mere presence of this process does not prove that the Netherlands are engaged in status-seeking behaviour. Still, it significantly increases my confidence in the hypothesis that international status-seeking played a role in Dutch decision-making. As discussed in the Method and Case Selection section, my low prior expectations mean that any evidence I found carries significant weight. These findings strengthen the existing literature on small-state status-seeking behaviour, adding another likely case to the set.

Discussion

Contributions to the field

By demonstrating the likely presence of a status-seeking mechanism in the fighter jet coalition for Ukraine, I begin to fill the research gap around status-seeking in alliance dynamics. Status-seeking may take the form of contributing through donations and coalition building. This constitutes an essential contribution to the field, as additional cases strengthen the literature. Moreover, the applicability of the generalised status-seeking concept to a new area is an exciting prospect. I also showed that the invitation-games model brought forward by Pedersen and Reykers (Pedersen and Reykers 2023) is present, strengthening that concept and extending it to donations and coalition-building.

Moreover, I introduced the idea that the US may consider the position of NATO Secretary General specifically as a reward. I made this likely by arguing that the position has been held consecutively by Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, a Dutchman; Anders Fogh Rasmussen, a Dane; Jens Stoltenberg, a Norwegian; and now Mark Rutte, another Dutchman. The literature around small-state status-seeking is mainly built around these countries (Ringsmose 2010; Ringsmose and Rynning 2009; Jakobsen, Ringsmose, and Saxi 2018; Pedersen and Reykers 2020; Pedersen and Reykers 2023) and the notion that status-seeking may lead to rewards, including opening doors for elites (Neumann and Carvalho 2015, 16). Thus, this observation is worth further investigation.

Future research

An initial subject of interest for further research would be Mark Rutte’s role in shaping the Dutch position in the F-16 coalition for Ukraine. Should currently classified information become publicly available, returning to this case study with a closer look at Rutte would be desirable.

Secondly, the model I derived hinges on international recognition impacting the willingness of alliance members to contribute. That implies that changes in (perceived) international recognition should result in tangible empirical changes to the contributions made. Thus, following the 2024 US elections, there may be opportunities to research whether a shift in recognition from the US leads to changes in NATO status-seeking dynamics. Of course, this would require other factors to remain sufficiently similar so that the impact of the recognition component could be adequately researched.

Conclusion

I hypothesised that the Dutch co-leadership of the fighter jet coalition for Ukraine was partly in the pursuit of international status. Accordingly, I used the process-tracing methodology to develop a status-seeking mechanism expected to be present in the Dutch decision-making process. After extensively researching available primary sources, I found that the process was likely present in this case.

The Netherlands gained international status in various US, Ukraine, and NATO public statements. I also suggested that Mark Rutte’s appointment as NATO Secretary General may be a reward from the US to the Netherlands, linking his appointment to the status-seeking literature. Moreover, I discussed the invitation-games model by Pedersen and Reykers (2023). A Danish document indicates the applicability of this mechanism to this case.

I remain aware of my low prior expectations of finding evidence of status-seeking. Therefore, informal Bayesian reasoning allows me to significantly upgrade my confidence in the hypothesis for each piece of evidence found. My findings thus increase substantially my confidence that status-seeking played a role in the Dutch decision to co-lead the F-16 coalition for Ukraine. This leadership included committing to donating a large portion of the Dutch F-16s to Ukraine and contributing 18 jets to the training centre in Romania. My hypothesis that “the Dutch decision to co-lead the fighter jet coalition for Ukraine was partly motivated by international status seeking” thus appears increasingly likely based on this research. Status-seeking is not the only factor involved (Jakobsen, Ringsmose, and Saxi 2018, 276). Moral considerations regarding Ukraine’s legitimate right to self-defence and security considerations about the territorial integrity of NATO countries are only some of the other explaining factors that arose from my empirical sources. Still, my findings indicate that status-seeking was likely a contributing factor. This implies that small-state status-seeking behaviour may take the form of donations and coalition-building, highlighting an essential contribution to the field.

Tables and Figures

Table 1: model of the presumed prestige-seeking mechanism in the formation of the F-16 coalition for Ukraine

Bibliography

Austin III, LLoyd J., and Mark A. Milley. 2023. “Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Mark A. Milley Hold a News Conference Following a Virtual Meeting of the Ukraine Defense Contact Group.” US Department of Defense. https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/3408923/secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-iii-and-joint-chiefs-of-staff-chairman-gene/.

Bayer, Lili, Cristina Gallardo, and Lara Seligman. 2023. “The F-16 Takeoff to Ukraine Will Take Time.” Politico Europe, May 22. https://www.politico.eu/article/f-16-jet-to-ukraine-will-take-time-pilot-training/.

Beach, Derek, and Rasmus Brun Pedersen. 2019. Process-Tracing Methods: Foundations and Guidelines. Second Edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Beale, Jonathan, and James Gregory. 2023. “F-16 Fighter Jets: Biden to Let Allies Supply Warplanes in Major Boost for Kyiv.” BBC News, May 20. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-65649471.

Brekelmans, Ruben, and S.W. Sjoerdsma. 2023. “Motie van de leden Sjoerdsma en Brekelmans over met bondgenoten starten met het trainen van Oekraïense militairen voor geavanceerde Westerse wapensystemen.” Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal. Kamerstukken 2, 2022–2023, 21 501-02, nr. 2641. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/kamerstukken/moties/detail?id=2023Z07346&did=2023D17232.

Brown, Benjamin, and Yulia Kesaieva. 2023. “Zelensky Hails ‘Historic’ Supply of F-16s as Ukraine Seeks to Counter Russian Air Supremacy.” CNN World, August 20. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/08/20/europe/netherlands-denmark-f-16-fighter-jets-ukraine-intl/index.html.

Clark, Joseph. 2023. “U.S. Will Train Ukrainian F-16 Pilots, Ground Crews.” DOD News. August 24. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3504621/us-will-train-ukrainian-f-16-pilots-ground-crews/.

Danish Ministry of Defense. 2023. “Denmark Will Take on Co-Lead Role in International Air Force Coalition to Support Ukraine.” October 11. https://www.fmn.dk/en/news/2023/denmark-will-take-on-co-lead-role-in-international-air-force-coalition-to-support-ukraine/.

De Lange. 2023. “Verslag van een commissiedebat, gehouden op 9 februari 2023, over NAVO Defensie Ministeriële en wapenleveranties aan Oekraïne.” Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal. Kamerstukken 2, 2022–2023, 28 676, nr. 428. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/downloads/document?id=2023D05927.

Derix, Steven. 2024. “‘Onwelgevallige informatie over Israël onder het tapijt geveegd.’” NRC, January 21. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2024/01/21/onwelgevallige-informatie-over-israel-onder-het-tapijt-geveegd-a4187658.

Dutch Government. 2023. “Statement on a Joint Coalition on F-16 Training of the Ukrainian Air Force.” Diplomatic statement. Government.Nl. July 11. https://www.government.nl/documents/diplomatic-statements/2023/07/12/statement-joint-coalition-on-f-16-training-of-the-ukrainian-air-force.

Dutch Ministry of Defense. 2023. “Defence to Make First 18 F-16 Fighter Aircraft Available to Ukraine.” December 22. https://english.defensie.nl/latest/news/2023/12/22/20231222-defence-to-make-first-18-f-16-fighter-aircraft-available-to-ukraine.

Dutch Ministry of Defense. 2024. “Nederland haalt F-16’s uit de verkoop.” February 5. https://www.defensie.nl/actueel/nieuws/2024/02/05/nederland-haalt-f-16s-uit-de-verkoop.

Economides, Spyros. 2024. “Four Questions about the West’s Future Support for Ukraine.” LSE Comment. February 23. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2024/02/23/four-questions-about-the-wests-future-support-for-ukraine/.

Hodunova, Kateryna. 2024. “Ukraine War Latest: Ukraine Signs Long-Term Security Agreement with Netherlands.” The Kyiv Independent, March 1. https://kyivindependent.com/ukraine-war-latest-ukraine-signs-long-term-security-agreement-with-netherlands/.

Jakes, Lara, and Eric Schmitt. 2023. “The Latest Flash Point Among Ukraine’s Allies Is Whether to Send F-16s.” New York Times, May 17. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/17/world/europe/ukraine-f-16-biden-netherlands-britain.html.

Jakobsen, Peter Viggo, Jens Ringsmose, and Håkon Lunde Saxi. 2018. “Prestige-Seeking Small States: Danish and Norwegian Military Contributions to US-Led Operations.” European Journal of International Security 3 (2): 256–77. doi:10.1017/eis.2017.20.

Kayali, Laura. 2023. “Europe Opens F-16 Warplane Training Center for Ukrainian Pilots.” Politico Europe, November 13. https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-open-f16-training-center-ukraine-pilot/.

Kent, Lauren, Julia Kesaieva, and Brad Lendon. 2023. “UK, Netherlands Are Working to Procure F-16 Fighters for Ukraine, Downing Street Says.” CNN World, May 17. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/05/16/europe/uk-netherlands-ukraine-f-16-fighters-intl-hnk/index.html.

Liebermann, Oren, and Natasha Bertrand. 2023. “US Commits to Approving F-16s for Ukraine as Soon as Training Is Complete.” CNN Politics, August 18. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/08/17/politics/us-f-16-fighter-jets-ukraine/index.html#:~:text=The%20US%20has%20committed%20to,training%20on%20the%20F%2D16.

Lopez, C. Todd. 2023. “F-16 Training, Aircraft, to Fill Ukraine’s Mid-Term, Long-Term Defense Needs.” DOD News. May 23. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3405085/f-16-training-aircraft-to-fill-ukraines-mid-term-long-term-defense-needs/#:~:text=Since%20the%20very%20first%20meeting,that%20long%2Dterm%20support%20plan.

Lukiv, Jaroslav. 2023. “Ukraine War: US Allows Transfer of Danish and Dutch F-16 War Planes to Kyiv.” BBC News, August 19. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-66551478#.

Méheut, Constant. 2023. “Russia Makes Small Battlefield Gains, Increasing Pressure on Ukraine.” New York Times, December 22. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/22/world/europe/russia-ukraine-war.html.

Mpoke Bigg, Matthew, and Vivek Shankar. 2023. “Ukraine Will Get F-16 Fighter Jets From Denmark and Netherlands.” New York Times, August 20. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/20/world/europe/ukraine-war-f16-jets.html.

NATO. 2024. “Mark Rutte NATO Secretary General 2024.” NATO Who’s Who. October 1. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/who_is_who_229125.htm.

NATO Air Command. 2023. “Twitter Post NATO Air Command of November 13 2023 on Opening the Training Center in Romania.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/NATO_AIRCOM/status/1724357279242166667.

Neumann, Iver B., and Benjamin de Carvalho, eds. 2015. “Introduction.” In Small States and Status Seeking: Norway’s Quest for International Standing, 1–21. New International Relations. London ; New York, NY: Routledge.

Ollongren, K.H. 2023. “Aanvullende Nederlandse bijdrage aan Oekraïense luchtverdediging,” June 14. Kamerstukken 2, 2022–2023, 36 045, nr. 164. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/downloads/document?id=2023D25957.

Oma, Ida Maria, and Magnus Petersson. 2019. “Exploring the Role of Dependence in Influencing Small States’ Alliance Contributions: A Reputation Mechanism Argument and Assessment.” European Security 28 (1): 105–26. doi:10.1080/09662839.2019.1589455.

Pedersen, Rasmus Brun, and Yf Reykers. 2020. “Show Them the Flag: Status Ambitions and Recognition in Small State Coalition Warfare.” European Security 29 (1): 16–32. doi:10.1080/09662839.2019.1678147.

Pedersen, Rasmus, and Yf Reykers. 2023. “Invitation Games and the Politics of Joining US-Led Coalition Warfare: A Small State Perspective.” International Relations, May, 004711782311665. doi:10.1177/00471178231166562.

Piri, Kati, and Caspar Veldkamp. 2023. “Motie van de leden Piri en Veldkamp over uitspreken dat Nederland een voortrekkersrol moet blijven spelen in het steunen van Oekraïne.” Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal. Kamerstukken 2, 2023–2024, 21 501-20, nr. 1993. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/kamerstukken/moties/detail?id=2023Z20056&did=2023D49008.

Posaner, Joshua. 2024. “Netherlands Pledges Six Extra F-16 Fighter Jets to Ukraine.” Politico Europe, February 5. https://www.politico.eu/article/netherlands-pledges-six-extra-f-16-fighter-jets-to-ukraine/.

Posaner, Joshua, and Paul McLeary. 2023. “US to Lead on Training Ukrainian F-16 Pilots.” Politico, October 11. https://www.politico.eu/article/us-to-lead-on-training-ukrainian-f-16-pilots/.

Prenger. 2023. “Verslag van een schriftelijk overleg over de geannoteerde agenda voor de Informele Raad Buitenlandse Zaken Gymnich van 12 mei 2023.” Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal. Kamerstukken 2, 2022–2023, 21 501-02, nr. 2650. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/downloads/document?id=2023D19472.

Raad Algemene Zaken and Raad Buitenlandse Zaken. 2023. “Verslag van een commissiedebat, gehouden op 19 januari 2023, over Raad Buitenlandse Zaken.” Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal. Kamerstukken 2, 2022/2023, 21 501-02, nr. 2603. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/downloads/document?id=2023D02315.

Ringsmose, Jens. 2010. “NATO Burden-Sharing Redux: Continuity and Change after the Cold War.” Contemporary Security Policy 31 (2): 319–38. doi:10.1080/13523260.2010.491391.

Ringsmose, Jens, and Viggo Jakobsen. 2017. “Burden-Sharing in NATO. The Trump Effect Won’t Last.” NUPI Policy Brief. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2468677.

Ringsmose, Jens, and Sten Rynning. 2009. Come Home, NATO? The Atlantic Alliance’s New Strategic Concept. DIIS Report, 2009:04. Kopenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies.

Roussi, Antoaneta. 2023. “Zelenskyy Hails F-16 Commitment on Visit to Netherlands.” Politico Europe, August 20. https://www.politico.eu/article/volodymyr-zelenskyy-mark-rutte-netherlands-ukraine-hails-f-16-commitment-on-visit-to-netherlands/.

Ryder, Pat. 2023. “Pentagon Press Secretary Air Force Brig. Gen. Pat Ryder Holds a Press Briefing.” https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/3501484/pentagon-press-secretary-air-force-brig-gen-pat-ryder-holds-a-press-briefing/.

Schaart, Eline. 2023. “Netherlands, Denmark Confirm US Has Approved Sending Ukraine F-16 Jets.” Politico Europe, August 18. https://www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-f16-jets-russia-war-netherlands-denmark-united-states/.

Schmitt, Eric, John Ismay, and Lauren McCarthy. 2023. “Allies to Be Allowed to Send F-16s to Ukraine, U.S. Official Says.” New York Times, August 17. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/17/world/europe/allies-to-be-allowed-to-send-f-16s-to-ukraine-us-official-says.html#:~:text=The%20jets%20can%20be%20sent,are%20trained%20to%20operate%20them

.&text=In%20a%20long%2Dawaited%20move,U.S.%20official%20confirmed%20on%20Thursday.

Seligman, Lara. 2023a. “‘Big Step’: U.S. Joins Major Effort to Train Ukrainian Pilots on F-16s, Other Jets.” Politico, May 19. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/05/19/fighter-jets-ukraine-biden-00097846.

Seligman, Lara. 2023b. “U.S. Gives Final Approval Allowing F-16 Training for Ukraine to Begin.” Politico, August 17. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/08/17/f-16-us-ukraine-denmark-netherlands-00111769#:~:text=The%20Biden%20administration%20has%20formally,according%20to%20two%20U.S%20officials.

Sheftalovich, Zoya. 2022. “Battles Flare across Ukraine after Putin Declares War.” Politico, February 24. https://www.politico.eu/article/putin-announces-special-military-operation-in-ukraine/.

Starling, Clementine G., Jacob Mezey, and Holly Ryan. 2023. “Here’s What F-16s Will (and Will Not) Mean for Ukraine’s Fight against Russia.” Atlantic Council. August 25. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/heres-what-f-16s-will-and-will-not-mean-for-ukraines-fight-against-russia/.

Tannehill, Brynn. 2023. “What F-16s Will (and Won’t) Do for Ukraine.” The RAND Blog. May 31. https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2023/05/what-f-16s-will-and-wont-do-for-ukraine.html.

The Economist. 2023. “How Soon Will Ukraine Be Able to Use Its F-16s?” The Economist, August 22. https://www.economist.com/europe/2023/08/22/how-soon-will-ukraine-be-able-to-use-its-f-16s?.

Threels, W.F.A. 2023. “Besluit op Woo-verzoek over bezoek Oekraïense president Zelensky aan vliegbasis Eindhoven.” Kabinet Mlnlster·Presldent, Dutch government. https://open.overheid.nl/Details/e42bfaf9-32ee-4284-8196-deb5a3ad58f3/1.

Trebesch, Christoph, Antezza, Arianna, Bushnell, Katelyn, Frank, André, Frank, Pascal, Franz, Lukas, Kharitonov, Ivan, Kumar, Bharath, Rebinskaya, Ekaterina, and Schramm, Stefan. 2023. “The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which Countries Help Ukraine and How?, Kiel Working Paper, No. 2218.” Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel), Kiel. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/270853.

Ukrainian Air Force. 2023. “Twitter Post Ukrainian Air Force of November 13 2023 on Opening the Training Center in Romania.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/KpsZSU/status/1724114164417785878.

Ukrainian Air Force. 2024. “Twitter Post Ukrainian Air Force of February 5 2024 on Six Extra F-16s Being Donated.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/KpsZSU/status/1754510510446301519.

Ukrainian Ministry of Defense. 2023a. “Twitter Post Ukrainian Ministry of Defense of November 13 2023 on Opening the Training Center in Romania.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/DefenceU/status/1724097294201426316.

Ukrainian Ministry of Defense. 2023b. “Twitter Post Ukrainian Ministry of Defense of December 22 2023 on Preparation of Dutch F-16s.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/DefenceU/status/1738270105711030369.

Ukrainian Ministry of Defense. 2024. “Twitter Post Ukrainian Ministry of Defense of February 5 2024 on Six Extra F-16s Being Donated.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/DefenceU/status/1754516838627553435.

Ward, Alexander, and Matt Berg. 2024. “No, the Biden Admin Doesn’t Want to Strike inside Iran.” Politico, February 5. https://www.politico.com/newsletters/national-security-daily/2024/02/05/no-the-biden-admin-doesnt-want-to-strike-inside-iran-00139581.

Zelensky, Volodymyr. 2023a. “Twitter Post Zelenskyy of May 19 2023 on Fighter Jet Coalition.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/ZelenskyyUa/status/1659590726840197123?lang=en.

Zelensky, Volodymyr. 2023b. “Twitter Post Zelenskyy of August 20 2023 Thanking the Netherlands.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/ZelenskyyUa/status/1693238151249096822.

Zelensky, Volodymyr. 2023c. “Twitter Post Zelenskyy of August 20 2023 Thanking the Netherlands and Denmark with Video.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/ZelenskyyUa/status/1693379762050265425.

Zelensky, Volodymyr. 2023d. “Twitter Post Zelenskyy of August 20 2023 Thanking the Netherlands, Denmark and US.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/ZelenskyyUa/status/1693334700276752851.

Zelensky, Volodymyr. 2023e. “Twitter Post Zelenskyy of November 13 2023 on Opening the Training Center in Romania.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/ZelenskyyUa/status/1724119886677381407.

Zelensky, Volodymyr. 2023f. “Twitter Post Zelenskyy of December 22 2023 on Calling Mark Rutte.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/ZelenskyyUa/status/1738176396923445692.

Zelensky, Volodymyr. 2024. “Twitter Post Zelenskyy of March 1 2024 Thanking Mark Rutte.” Twitter. https://twitter.com/ZelenskyyUa/status/1763572751036506593#.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Iceland and the Vatican City: Small State Agency in International Politics

- Game Theory and Non-Alignment: India’s Position in the Russia-Ukraine War

- Evaluating Russia’s Grand Strategy in Ukraine

- State Failure or State Formation? Neopatrimonialism and Its Limitations in Africa

- How the Islamic State Weaponizes Imitation in Its Propaganda

- The State of and Prospects for Space Governance: A Critical Deliberation