When Wallace S. Broecker first coined the term global warming in 1975, it was regarded as a distant challenge. Decades later, climate change is no longer a hypothetical concern but a lived reality, with its disruptive impacts felt globally. While nations work to mitigate emissions, existing changes to the climate are already causing widespread devastation. Among the most vulnerable are India and the Global South, given their dense populations and geographic diversity. Although India has taken significant steps toward a green transition, the focus remains heavily skewed towards climate mitigation rather than adaptation. This imbalance is further exacerbated by private sector hesitancy to invest in adaptation projects, placing the onus squarely on government-led public expenditure to address these pressing needs.

India’s public investments in climate initiatives have predominantly centered on mitigation, leaving adaptation measures underfunded. For instance, the National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change (NAFCC), set up to support adaptation projects, has experienced a steady decline in funding. Allocations fell from INR 115.36 crore in 2017-18 to a mere INR 34 crore in 2022-23. Simultaneously, India’s energy transition is advancing rapidly, with the country ranking 63rd on the World Economic Forum’s Energy Transition Index and moving steadily toward its 2030 goal of 500 GW renewable energy capacity.

While these advancements in renewable energy are critical, they are primarily aimed at reducing emissions rather than addressing the immediate and long-term consequences of climate change. Even if net-zero emissions were achieved today, the residual effects of existing greenhouse gases would linger for decades. This stark reality makes it imperative to invest in building resilience and creating adaptive systems capable of withstanding the ongoing impacts of climate change.

The prioritization of mitigation over adaptation is not unique to India and is evident worldwide. This preference is particularly pronounced in private investment trends. According to a Boston Consulting Group (BCG) study, only 36% of investors in India see potential in adaptation-related projects, compared to 42% who favor mitigation themes such as renewable energy generation. Additionally, half of these investors show little inclination to fund projects aimed at humanitarian responses and community resilience.

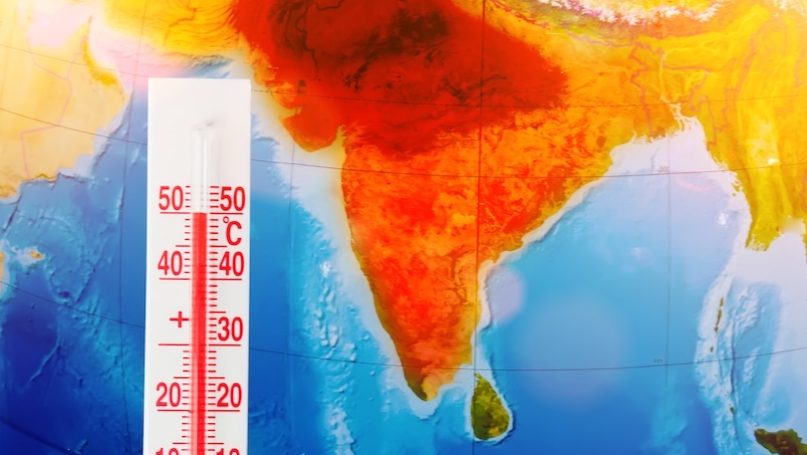

This hesitancy stems from the complex nature of adaptation projects, which are perceived as riskier due to uncertain outcomes and indirect benefits. Unlike mitigation, which often yields measurable results like emission reductions, adaptation efforts typically focus on public welfare and lack direct financial returns. As such, the responsibility for implementing these critical initiatives falls primarily on governments. Recent events, such as catastrophic floods in Uttarakhand and severe heatwaves in northern India, underscore the urgency of strengthening climate adaptation efforts.

The climate crisis must be addressed through a multifaceted approach that goes beyond emission reduction targets. Building resilience requires integrating adaptation measures into broader developmental policies and fiscal strategies. Public budgets play a pivotal role in determining how climate goals are aligned with national economic priorities such as GDP, employment, and income. The challenge lies in reshaping public expenditure frameworks to adequately accommodate and prioritize climate adaptation.

India’s commitment to the idea of green GDP, as emphasized by the Prime Minister, represents a promising step. However, domestic fiscal policies must extend beyond abstract concepts and redefine development itself to embed adaptation measures across all sectors. Investments in renewable energy and energy storage technologies alone will not suffice unless public expenditure frameworks cohesively address both mitigation and adaptation challenges.

At its core, budgeting is about balancing competing priorities and allocating limited resources to maximize public welfare. However, adaptation continues to receive insufficient attention within this process. Estimates from the Climate Policy Initiative suggest that India requires annual investments between USD 14 billion and USD 67 billion for adaptation-related development interventions between 2015 and 2030. Yet, allocations to the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) have consistently remained at a mere 0.1% of the total budget.

To rectify this imbalance, India must incorporate climate risks into its fiscal planning. One effective approach involves integrating physical and economic risks of climate change into macroeconomic forecasting. Development projects often overlook long-term climate impacts, such as recurring floods or heatwaves, leading to unsustainable debts and incomplete projects. Accurate fiscal models can enable governments to project these risks and allocate resources accordingly, creating a more realistic and sustainable planning framework.

Effective adaptation requires collaboration across sectors and institutions. Transitioning from labor-intensive industries to low-carbon sectors will demand reskilling and training workers for roles in renewable energy technology production, installation, and operation. Such initiatives require coordinated planning and cross-sectoral expenditures, which India’s current single-agency administrative structure does not adequately support. Reforming program budgeting to facilitate multi-agency collaboration is essential for creating a robust adaptation framework.

One of the major barriers to effective adaptation funding is the lack of mechanisms to track climate-related expenditures. Climate budget tagging (CBT) offers a potential solution. By categorizing and monitoring funds allocated for climate-relevant projects, CBT helps identify gaps and ensures resources are directed toward underfunded areas. Nepal’s CBT system, for instance, tracks climate expenditures and evaluates their alignment with national climate goals. Adopting a similar mechanism in India, tailored to its diverse climate challenges, could institutionalize adaptation spending and enhance accountability in public expenditure.

The 2024-25 Union Budget reflects the challenge of balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability. However, disparities in funding allocation persist—mitigation efforts saw a 48.15% increase in 2023-24, while adaptation spending rose by a meager 1.63%. Such trends highlight a fundamental flaw in India’s climate strategy, where adaptation continues to be an afterthought. To address this, India must adopt budgetary practices that quantify the long-term benefits of climate-resilient development. Integrating adaptation into fiscal planning will not only align domestic policies with global climate commitments but also ensure that public expenditure supports sustainable growth. By institutionalizing these changes, India can pave the way for a resilient and sustainable future, ensuring that the country is well-prepared to face the challenges of a changing climate.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- India’s Health and Climate Inequities: Navigating the Global North-South Divide

- Opinion – The World Bank’s Comprehensive Climate-Centric Transformation

- Opinion – Pakistan Hatred Sells in Modi’s India

- With Great Power Comes Great Climate Responsibility

- Opinion – Black and Southern Feminisms Matter in the Global Climate Struggle

- Opinion – Protest, Interrupted? Climate Activism During the Coronavirus Pandemic