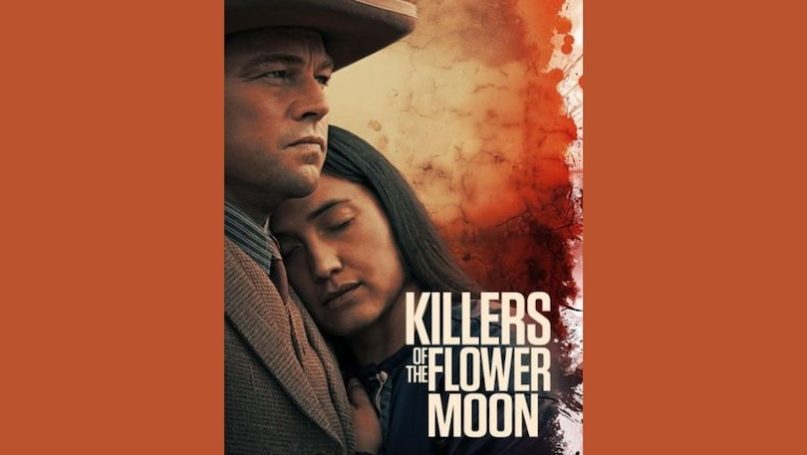

Killers of the Flower Moon

Directed by Martin Scorcese, 2023

At the heart of this movie are the rights of indigenous peoples, the malfeasance of corporate and political obstacles, and the challenges faced by first nation peoples. It depicts the tapestry of indigenous struggle and encourages local mobilization in ensuring the empowerment of such groups in the USA and across the world. This movie is an adaptation of the 2017 multi-award-winning novelette, Killers of the Flower Moon, written by David Grann. Produced by Dan Friedkin and others, the film production stars Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro, and Lily Gladstone. In content it is essentially an American epic western crime drama, but its subplot is about the birth pains of global indigenous power.

Set in 1920s Oklahoma, it focuses on a series of mysterious murders of leading members of the Osage Nation after oil was discovered on tribal land. The tribal members had retained mineral rights on their reservation, but a corrupt local political boss sought to steal the wealth. The film premiered at the 76th Cannes Film Festival on May 20, 2023 and received critical acclaim, with praise for the movie’s integrity, Scorsese’s direction, the screenplay, cinematography, musical score, and cast performances (especially DiCaprio, Gladstone, and De Niro), although the long runtime (well above industry average) received some criticism.

There is much in the plot and the message of this film which will be of special interest to instructors and students of international relations. It would, for example, serve as a worthy resource for classroom discussion of indigenous rights, environmental protection, multinational governance, political mischievousness and many other kindred themes. If an IR instructor is looking for a modern exemplar of Machiavelli – this movie has one. In Grann’s insightful book and Scorsese’s empathetic portrayal, many themes relevant to IR are paramount. The pertinence to our IR literature is apparent from the opening scene. Thus, we see Osage Nation elders bury a ceremonial pipe, mourning their descendants’ assimilation into White American society.

What follows is something of an expose of the existential reality of the “mixed blessings” of life. An indigenous peoples experience an apparently “rags to riches” story, only to be confronted by tragedy. Blissfully wandering through their Oklahoma reservation, during the annual “flower moon” phenomenon of fields of blooms, Osage tribal members discover oil. The tribe becomes wealthy, as it retains mineral rights and members share in oil-lease revenues, though the racist laws of the times required white court-appointed legal guardians, assuming first-nation peoples to be intellectually “incompetent”.

The challenge of global racism is a staple of the international relations curriculum. This genre of (less than) subtle racism in the American south is familiar, and receives less attention in IR than it deserves, primarily because we are familiarized into thinking of the USA primarily as a universal “success story”. In many ways this movie is a continuation of the message of residual racism portrayed in Green Book , a 2018 American biographical comedy-drama film inspired by the true story of a 1962 tour of the Deep South by African American pianist Don Shirley. This cosmeticized but (in reality) state-sanctioned racism should be a recurrent theme in the analysis of indigenous peoples in the IR classroom. IR students will find even more direct evidence in Killers.

Scorsese also offers a subtle parody of the famous Rodgers and Hammerstein, Oklahoma, by fleeting references to the hermetically sealed conduits of black and white life in the American south. A newsreel of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre, in which numerous black residents were murdered, traumatized the Osage. Thematic analysis of Grann and Scorsese’s story-telling differentiates between Killers of the Flower Moon and traditional Westerns in the old Hollywood tradition.

Jorge Cotte of The Nation suggests: “Unlike the visions of unbounded freedom found in traditional westerns, Martin Scorsese’s new film is a study of a West bounded by the vertical geometry of oil rigs and the violent conspiracies of powerful men.” Cotte then clarifies some of the thematic differences. Grann’s book recounts the unsolved crimes tormenting Osages from 1921 to 1926, and the intervention of the Bureau of Investigation (the FBI’s predecessor). Grann diligently contextualizes mass-murder and, J. Edgar Hoover’s subsequent role in shaping the bureau. Scorsese’s retelling simplifies the story by focusing on how an individual descends, “through greed, complicity, and cowardice, into unforgivable acts of despoliation and violence.”

Scorsese centrally involved the Osage Nation in the film’s production. He met Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear in Pawhuska and sought full involvement. He cast Osage actors in numerous roles, and hired hundreds of tribe members as background extras and production crew to ensure accurate portrayal of the tribe. Osage translator Christopher Cote taught the actors the Osage language.

Frequent Scorsese collaborator Robbie Robertson (himself of Cayuga and Mohawk ancestry) composed the incidental score. Critics have described it as “old-timey”. This reviewer would suggest that it is a sincere and lyrically haunting effort to reproduce authenticity. The film also features a soundtrack of popular music from the 1920s and Native American songs. It was Robertson’s final completed film score before he died in August 2023. The film is dedicated to his memory. It is a significant achievement and suitable tribute to Robertson.

The film’s genuine coda drew public respect and even acclaim for its acknowledgement of the historical silencing of crimes committed against Indigenous peoples, with Joel Robinson of Slate writing the scene, “turns the camera both inward and onto the audience simultaneously”, and The New Yorker’s Richard Brody noting, “Scorsese’s control of form and tone, and the bold yet subtle way that he marshals incident, signal that he is intent not merely on narrating history but on troubling the conscience of his (doubtless largely white) audience”. These are matters which will be pondered by the IR community since we are particularly anxious that about how such films are received among the communities they seek to portray.

There appears to be broad agreement among indigenous peoples that the drama succeeded in accurately portraying the culture and language of the Osage peoples. On November 9, 2023, the day that the SAG-AFTRA strike ended, Lily Gladstone posted a beautiful message of acclimation to the Osage Nation, widely re-posted on social media encouraging Native people to view it, “when and only if you feel ready, and see it with people you feel safe with…” Lily was very much conscious that the Osage would likely have a lot of generational grief to process.

There is so much in this film which will excite and engage instructors and students of IR. It is a beautiful exemplar of the travails and injustice of indigenous peoples, but it also a celebration of their resilience and remarkable potential. These are subjects we should be treating with pride and enthusiasm in our IR classrooms.