The enduring belief that the so-called developed West is immune to corruption has been firmly challenged. Numerous contemporary examples demonstrate that unethical practices are prevalent at the highest levels of government in Europe and the U.S. A recent report highlighted serious corruption risks related to 135 grossly overpriced health procurement contracts in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic, totaling £15.3 billion. Individuals closely associated with the European Parliament have faced accusations of accepting bribes in exchange for political favors. Additionally, the current mayor of New York City has been charged with abusing his position to take bribes and solicit illegal campaign contributions. Unsurprisingly, a majority—62 per cent—of Americans believe that corruption is widespread in the U.S. and that the government primarily serves the interests of its elites rather than the common good. Similarly, more than two-thirds of Europeans also consider corruption to be widespread in their country, expressing concerns that high-profile corruption cases are not investigated sufficiently.

Despite decades of efforts by states and intergovernmental organizations to combat corruption, citizens worldwide are increasingly skeptical about the effectiveness of such initiatives. Corruption is no longer seen as an issue confined to the Global South or the post-socialist region; it has become a reality for many citizens who live in countries, such as Sweden or Germany, that are conventionally considered to be free from it. This highlights that corruption is indeed a global concern. However, such failed anticorruption efforts suggest that we still do not fully understand how corruption really operates.

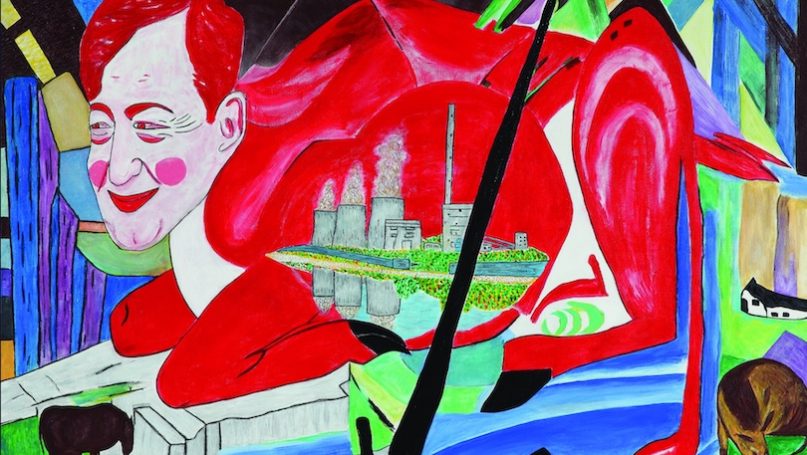

Economists, legal scholars, and political scientists have extensively researched and conceptualized corruption; however, their efforts have often fallen short of fully capturing a crucial aspect: the social dimensions of the phenomenon. My book, Sociology of Corruption, provides a meso-level sociological analysis to get a more precise and more comprehensive image of how corruption works. The research demonstrates a compelling blend of theoretical insight and empirical rigor and discusses implications for practice, while remaining accessible to a broad audience. Specifically, it provides the insight that more comprehensive understandings of corruption could lead to the development of more tailored and effective anticorruption measures. While it focuses on Hungary as a case study, the theoretical framework and policy recommendations apply to other nations and cultural contexts. This novel approach highlights that corruption is not merely an economic, legal, or political issue but fundamentally a sociological one.

According to the 2023 Transparency International CPI index, Hungary has emerged as the most corrupt member of the European Union. Researchers and experts unanimously agree that a group of corrupt political actors captured most state institutions and a significant portion of the business and cultural sectors in contemporary Hungary, and have been using these positions to extract enormous amounts of resources from the system. However, an analysis of Eurobarometer data based on representative EU-wide samples reveals that every year, fewer and fewer Hungarians have reported personal involvement in corruption over the past twelve months. The percentage of respondents who experienced or witnessed corruption decreased from nearly 30% in 2005 to 14% in 2019. This raises an intriguing question: how can a country seem to become less corrupt while simultaneously being classified as more corrupt? The answer, one of the central findings of this book, is that various forms of corruption coexist, with the role and significance of each type continuously evolving.

The sociology of corruption enhances our understanding of the phenomenon through some key areas. First, developing a middle-range sociological theory of corruption it addresses a long-standing gap in the literature, still dominated by the simplistic utilitarian concept of economics and political science, that treats corruption as the same harmful profit-maximizing activity worldwide. In contrast, my book argues that corruption is a multifaceted phenomenon that manifests itself through multiple forms. Relying on Karl Polanyi’s idea of the general historical forms of resource transfer — market exchange, reciprocity, and redistribution – and a second dimension, the primary beneficiary of corruption on the bribe-giver client side (individual, social group, or organization), I have developed a typology that covers most major forms of corrupt activities: market corruption, social bribe, corrupt organizations, and state capture.

Market corruption is a one-time low‐level form of corruption in which a street‐level bureaucrat (agent) who controls the provision of public goods and services “sells” their discretionary power to an individual (client). This is corruption between two strangers who do not know each other and probably will not meet again. Bribing traffic police on the spot to avoid a speeding ticket, a widespread practice in many countries, is a typical example of market corruption.

The second type, social bribe, relies on long‐term social ties instead of an ad hoc impersonal transaction and may involve multiple members of a social group on the client side, such as family or friendship networks, allowing repeated trust-based exchanges. Informal institutions in different cultures, like blat in Russia, compadrazgo in Chile, guanxi in China, or wasta in the Middle East, are ways of getting things done through personal contacts. Many transactions conducted through these institutions are not necessarily corrupt, yet they can also serve as ready-to-use infrastructure for social bribe transactions.

The corrupt organization type arises when an entire company is the client and the primary beneficiary of illicit conduct. In this scenario, corruption occurs within the company when employees participate in dishonest activities, such as securing government contracts through kickbacks to achieve the organization’s legitimate goals, like maximizing profits or increasing market share.

State capture is the most serious and sophisticated form of corruption. Here, narrow political and economic interest groups take control of state institutions and processes through which public policy is made, directing such policies away from the general public’s interest and instead shaping it to serve their own interests. For example, they often tailor huge public tenders or concessions to benefit a particularistic actor.

Secondly, this approach highlights the often-overlooked sociological aspect, demonstrating that the individuals involved in corruption are embedded in multiple layers of social life. Focusing on resources, we learn how and why goods and other immaterial things, such as recognition, honor, or prestige, are exchanged and transferred in corrupt transactions. This novel sociological perspective enhances the social scientific comprehension of the issue. It also shows that some forms of corruption are not ultimately negative. Beyond personal gains, social bribe may have social functions, such as maintaining the stability of social systems, keeping social groups together, or integrating new group members. Helping friends and family members in an illicit way is often morally justified and not regarded as corrupt by the local actors. Moreover, rather than being manifestations of deviance, some forms of corruption are social corrections of dysfunctional political and market institutions. For example, several economies and governments generate a shortage of goods and services that forces citizens to try to obtain those things corruptly as a response to the situation.

A further contribution that this research makes to anticorruption practice and scholarship is developing a qualitative methodology, which incorporates more than 100 in-depth interviews and press analyses of cases exposed by investigative journalists and immerses the reader in the concealed realm of corruption. Using narratives of people who actively participated in corruption or had first-hand experience, the research offers unique insights into the meanings and perceptions of the topic from the viewpoints of local actors. This sheds light on the motivations and social constraints that influence the individuals involved. Using this approach facilitates an understanding of how corruption is embedded in micro-level social relationships, organizational hierarchies, and situations intentionally crafted by the actors; or those that arise accidentally, as well as within larger structures, cultural contexts, social strata, and historical patterns.

My research focuses on these larger structures, providing a comprehensive look at the history of corruption in Hungary after the collapse of the socialist system in the late 1980s and the evolution of different types of corruption. As in the early 2000s, oligarchic state capture and, after 2010, political state capture became dominant forms of grand corruption in Hungary — large segments of the economy fell under the control of corrupt elites. Using the qualitative methodology in this case demonstrates how corruption in Hungary has been “monopolized” by these corrupt elites while other less severe forms have not been tolerated anymore by those in power.

Finally, a sociology of corruption has important implications for practice, and it may serve as a valuable resource for policymakers worldwide who aim to enhance decision-making about corruption. Most importantly, practitioners must recognize the specific nature of the corruption they encounter. The overarching policy implication of the qualitative methodology findings in Hungary is that anticorruption strategies must be tailored to the specific types of corruption rather than relying on generic, one-size-fits-all solutions often recommended by international organizations such as the UN, OECD, IMF, World Bank, and global NGOs. It suggests that anticorruption measures can be effective when they concentrate on the actual scenarios in which corruption occurs. To identify these corruption types effectively, policymakers should engage more closely with the phenomenon and gain insights into the operations of specific offices, departments, agencies, local governments, public projects, or procurement systems.

Using a fresh sociological perspective in anticorruption practice enriches our understanding of the often-hidden phenomenon of corruption. Crucially, this methodology is applicable to corruption contexts both in Western and non-Western countries. The book’s deeper insights into corrupt practices can help us understand that certain forms of corruption are not necessarily net negative. Corruption may have the function of keeping social groups, such as family or friendship networks, together. Moreover, some forms of corruption are society’s responses to the defects of political or market institutions. In this case, corruption is just a symptom, so effective policy should address the broader social problems.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – The Domestic Roots of Xi’s Global Anti-Corruption Campaign

- Opinion – Nigeria’s Readiness to Fight Corruption and End Poverty

- What Do We Know about Alliances and Military Spending?

- Opinion – Nigeria’s Stagnation on Anti-Corruption Links with Growing Insecurity

- Process Sociology and the Global Ecological Crisis

- Critical Terrorism Studies Today: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going?