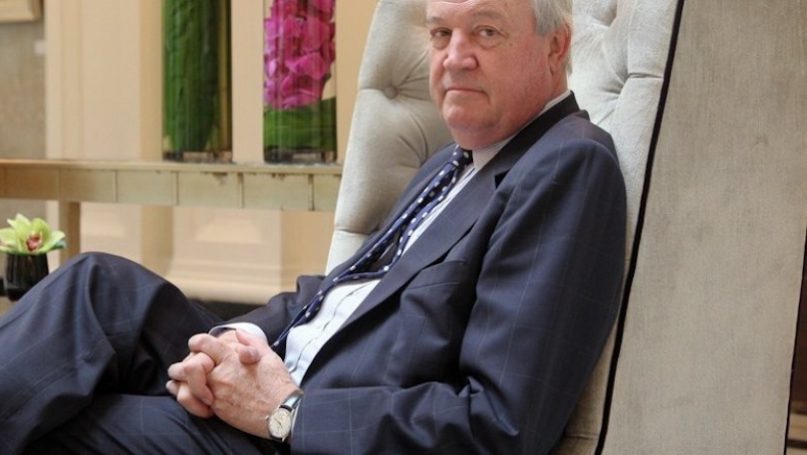

Jorge Heine is Interim Director of the Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future and Research Professor at the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies, Boston University. He specializes in the international politics of the Global South and diplomatic studies. A recipient of the 2023 Adil Najam Prize for Advancing the Public Understanding of Global Affairs, he has served as Vice-President of the International Political Science Association (IPSA), Global Fellow at the Wilson Center, Guggenheim Fellow, and Distinguished Fellow at the Center for International Governance Innovation (CIGI). He has also held senior research and visiting fellow roles at institutions including the China Center for Globalization and UN ECLAC and was twice named among South Africa’s 100 most influential personalities by The Star in 1997 and 1998.

Heine has authored, co-authored, or edited 18 books, including The Non-Aligned World (Polity, 2025), Latin American Foreign Policies in the New World Order (Anthem, 2023, 2024), and The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy (OUP, 2013, 2015), as well as over 130 scholarly articles. He holds a PhD and MA in Political Science from Stanford University, a B.Phil. from York University (UK), and a law degree from the University of Chile. A former Chilean Cabinet Minister and Ambassador to China, India, and South Africa, he has also held academic appointments at Wilfrid Laurier University and the universities of Konstanz, Oxford, Paris, and Tsinghua.

Where do you see the most exciting debates happening in your field?

As I see it, the most exciting debates in IR at this moment are happening in the growing field of Global IR. The pioneering work of Amitav Acharya in recent books like The Once and Future World Order (2025) and Divergent Worlds (2025), as well as in his previous volumes, have lifted the discipline from the narrow confines of the North Atlantic to the broader setting of the world in toto. This has considerably enriched the study of IR, brought new perspectives into play, and allowed us to see and to understand phenomena that we did not grasp previously. Acharya’s notion of multiplexity is an especially useful one, and much more nuanced and differentiated than that of multipolarity that is so widely used. I also find the work of Kishore Mahbubani on the rise of Asia and the debates around that especially illuminating. The same goes for the work of Malaysian political scientist Cheng-Chwee Kuik on hedging.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

Although I am originally from Chile, I started my academic career in Puerto Rico studying the Caribbean, a fascinating part of the world, whose magie antillaise still enthralls me. The challenges faced by these former plantation societies as they made the transition from their previous colonial condition to independence were extraordinary, and I was lucky to do fieldwork in Puerto Rico, Haiti and Grenada, among other places, getting a first-hand impression of the Caribbean predicament. Having later lived in South Africa, India and China, I was struck by the commonalities of developing nations and how difficult it is for them to establish productive, non-subordinate links with the international environment.

A natural extension of my work on the Caribbean was the study of Latin American IR and foreign policies, which I did for a while in Chile. Later, I extended this work to the broader Global South, where I had the chance to familiarize myself with African and Asian realities. Perhaps the most significant shift in my thinking came about when I realized that contrary to what dependency theorists postulated in the 1960s (many of whom were based in Santiago when I did my law studies at the University of Chile and thus shaped the thinking of many of my generation), it was possible to escape the ‘underdevelopment trap.’ The so-called ‘Asian Tigers’ did so in the latter part of the 20th century, and several emerging economies and rising powers are doing so now. Among the courses I teach at Boston University, perhaps my favorite is North-South Relations (IR 395), whose title has a nice, old-fashioned ring. The transition from the Third World of yesteryear to the New South of today is a running thread in it.

Alongside other scholars and practitioners, you have been advocating for the resurgence of the Cold War-era concept of non-alignment as a lens for analyzing contemporary power dynamics and foreign policy options. What drives your belief in the relevance of this concept today, and how do you see it shaping academic discourse and policymaking?

As a result of growing tensions between the United States and China during the first Trump administration (2017-2021), Latin America found itself under severe pressure from both Washington and Beijing to toe their respective lines. Major physical and digital infrastructure projects were cancelled because of those pressures. With my colleagues Carlos Fortin and Carlos Ominami, we concluded that, under such circumstances, which overlapped with the most significant economic downturn in the region in 120 years (in 2020), a new approach was needed to navigate this complex international environment. The latter had some similarities with the Cold War but also significant differences. We thus took a page from the Non-Aligned Movement of the fifties and sixties and adapted it to the realities of the new century, labelling it Active Non-Alignment (ANA). Our contribution proposes that, in the 21st century, there is a New South that has come into its own. It can rely on what has been called ‘collective financial statecraft,’ in marked contrast to the diplomatie des cahiers des doleances practiced by the NAM in its heyday, among other things, through requests for a New International Economic Order (NIEO).

The extant great power competition between the United States and China offers developing nations a remarkable opportunity: they can pick and choose, on an issue-by-issue basis, whether Washington or Beijing offers the best conditions for any project, be it a port, a dam or telecom technology. Today’s competition between the U.S. and China is different from the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union because of the relative size and openness of the Chinese economy. This offers more opportunities for developing nations in trade, investment and financial cooperation than the Soviet economy ever did. By “playing the field” and hedging their bets, weaker states are better off than by aligning themselves with China or the U.S. This allows them to deal with uncertainty while increasing their leverage. Our edited volume, Latin American Foreign Policies in the New World Order: The Active Non-Alignment Option (Anthem Press), with chapters by the former foreign ministers of six Latin American countries, was widely reviewed, and released in New Delhi by Indian foreign minister, S.Jaishankar. Colombia and South Africa have proclaimed Active Non-Alignment as their official foreign policy doctrine, and Itamaraty, the Brazilian foreign ministry, also uses the approach.

Your work often links active non-alignment to Latin America’s role in the global order. How feasible is for Latin American countries to operationalize active non-alignment while navigating the competing influences of the U.S., China, and Russia?

The Spanish edition of our book, with the title El No Alineamiento Activo y America Latina: Una doctrina para el nuevo siglo (Editorial Catalonia), was published in November 2021 in Santiago and triggered much interest across the hemisphere, with launches in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Peru, Mexico, and the United States. However, interest in the book and the notion of Active Non-Alignment soared after the Russian invasion of Ukraine three months later, in February 2022. It was then that many countries in the Global South, most prominently India and South Africa, but many others as well, took a different stance from that of Western powers on the war in Ukraine, especially on the unilateral sanctions applied on Russia. Suddenly, non-alignment was back with a vengeance, not just in Latin America but also in Africa and Asia, and this book provided a manual of sorts for it. From 2022-2024, not only the war in Ukraine but also the expansion of the BRICS group at their Johannesburg summit in August 2023, and later the war in Gaza, led to an upsurge of the Global South’s involvement in world affairs. South Africa took the lead in bringing a case against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), accusing it of violating the Convention Against Genocide. Brazil, in turn, as chair of the United Nations Security Council, introduced a resolution calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. United Nations General Assembly votes calling for a ceasefire in Gaza would garner 140 plus votes, mostly from the Global South, versus 50 or so against it, mostly from the Global North. Foreign Policy proclaimed 2023 the year of the Global South.

In many ways, Active Non-Alignment is the natural foreign policy of the Global South, which led us to write a follow-up companion volume to our first book on the subject. This monograph will be published in April 2025 by Polity Press, titled The Non-Aligned World: Striking Out in an Era of Great Power Competition. This book extends our argument from Latin America to the Global South, including examples and case studies from Africa and Asia. That said, it is essential to underscore that ANA is not a movement but a doctrine, a certain approach to foreign policy that provides an action guide and a compass for navigating the turbulent waters of a world in turmoil. ANA arose from the urgency of coming up with a response in Latin America, hit by a triple whammy: the COVID-19 pandemic, the ensuing recession, and the pressures from the Trump administration. As the second Trump administration (2025-2029) wreaks even more havoc in the existing world order, and U.S.-China competition shows no sign of abating, ANA becomes even more relevant – not just for Latin America, but for the Global South as a whole.

Tapping into your diplomatic career, how have your ambassadorial experiences in China, India, and South Africa shaped your perspectives on non-alignment from the Global South?

I am what, in Washington D.C., is known as an ‘in-and-outer,’ that is, someone who has alternated his professional career between academia and government service. I have spent two-thirds of my working life in universities and public policy think tanks on three continents and one-third in government service. I have also been fortunate in my ambassadorial appointments, both in terms of my destinations and their timing. They provided me with a unique, front-row seat on history. I was posted to South Africa from 1994-1999, for most of the presidency of Nelson Mandela, and I was the first ambassador to present credentials to him, also having the opportunity to work closely with him and with Archbishop Desmond Tutu in the creation of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In addition, I served in India from 2003 to 2007, during the heady days when the Indian press coined the term ‘Global Indian Takeover.’ The sky seemed to be the limit regarding what India, which was growing at 7-8 percent a year, could achieve. In those years, Chile made its first presidential visit to India, and I signed a bilateral trade agreement, the first of any Latin American country with India. Later, I was posted in China from 2014 to 2017, during much of Xi Jinping’s first term in office, with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the founding of the Asian Investment and Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) in their initial stages. During my time in China, Beijing was a key diplomatic hub, with many summits and state visits, including Chilean President Michelle Bachelet, who visited China twice during my tenure.

Having served in three of the five original BRICS countries, I learned there is a whole new world in Africa and Asia. After leaving behind their colonial shackles and centuries of humiliation and discrimination, countries in these continents are creating new institutions and giving new meaning to international solidarity—as shown so eloquently by South Africa’s actions before the ICJ on the war in Gaza. There is an energy and a future orientation very different from the weight of the past and from the trend to build walls and not bridges to the rest of humanity that prevails in North Atlantic countries today. Active Non-Alignment thus resonates as the best way to cope with an ever more uncertain and unpredictable environment.

Having served as ambassador to three long-standing BRICS members, how do you view the group’s current expansion process in light of Joseph S. Nye’s critique that BRICS is ‘neither representative enough nor sufficiently united to lead others’?

I actually discussed this with Joe Nye when I hosted him recently at the Pardee Center for a book talk on his memoirs, A Life in the American Century, which is a fine book. Nye’s arguments against the BRICS and their likely impact on world politics underestimate the degree to which it constitutes a platform that has evolved into a major reference point for the Global South precisely at a time when the West is both turning inwards and breaking up. Putting aside my conversation with Joe Nye, however, Western analysts in general have tended to be very critical of the BRICS. I disagree with them. First, critics said that the BRICS was just a talking shop: when the group came up with a bank, it was said that the bank would not work; when the New Development Bank proved its mettle, it was said that it was still smaller than the World Bank; when the BRICS had only five members, it was said that it was too small; now that it has ten with Indonesia on board, it is said that it is too big, and will not be able to agree on anything. And so it goes. On the argument that it is not representative, let’s remind ourselves that BRICS has countries from four continents. It may be true that the BRICS countries cannot agree on some things; but they are not in an alliance, they are a platform, and perhaps the best the Global South has available right now. It is not a platform of the Global South (China and Russia are not part of it) but for the Global South–in a way that the G7 is certainly not. By this I mean that the BRICS group puts the development concerns of Africa, Asia and Latin America front and center, established a bank for those purposes, and otherwise has shown its commitment to respond to those concerns.

More than a decade after co-editing the widely-cited Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy with Andrew F. Cooper and Ramesh Thakur, which challenges discussed in the book remain unresolved and need urgent attention in light of current events in the world?

The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy has been one of the most engaging academic projects I have participated in. Together with my co-editors, Andrew F. Cooper and Ramesh Thakur, it took us four years to compile this handbook. We successfully gathered an exceptional group of contributors, including prominent figures like former Canadian Prime Minister Paul Martin and Joe Nye, among others. Published in 2013, the handbook is regarded as the most comprehensive and ambitious diplomatic manual available in any language. Its flexible framework — centering on the transition from what I refer to as ‘club diplomacy’ to ‘network diplomacy’ — continues to serve as a valuable approach to understanding the evolving nature of statecraft in the new century.

The handbook is also Exhibit A of another change, namely that of looking at diplomatic studies through the lenses of IR rather than those of history or international law, as was the case in the past. Over the past decade, the book has led to a veritable boom in diplomatic studies. Thus, in 2025, the International Studies Association (ISA) Diplomatic Studies Section reached an all-time high of 498 members (a 16 percent increase from the previous year and the highest such increase of any of the 34 ISA sections and caucuses) and held 63 sessions at the ISA meetings in Chicago in March 2025.

What did we miss in the handbook? We should have included a chapter on the changing nature of diplomatic protocol, often dismissed by outsiders as a somewhat frivolous dimension of diplomacy. However, that has acquired more and more significance with the increase in summitry and in state visits, and logistics taking center stage. Although still in its infancy then, a chapter on what was then known as e-diplomacy (now digital diplomacy) would have been advisable, but fortunately that void has now been filled by my good friend Corneliu Bjola’s Oxford Handbook of Digital Diplomacy,published in 2024.

Having transitioned between diplomacy and academia, how has your experience shaped your perspective on both fields, and what advice would you give to practitioners and scholars considering a career shift between these domains?

From my youth, I have always been fascinated by world affairs and what it takes to make a difference. Studying IR with the likes of T.V. Sathyamurthy at York University and then with Richard Fagen, Alexander L. George, Robert O. Keohane and Robert North at Stanford University gave me the tools to analyze and make sense of international politics.

Working at the Wilson Center in Washington, DC, in the early eighties, led me to grasp the importance of public policy think tanks as conduits to bring together high-ranking officials and scholars. I have been associated with a number of these strange creatures we call think tanks on many continents ever since. They play a key role in crafting ideas and bringing them to the attention of policymakers. I was very fortunate to apply the insights gained from my studies when I had the chance to do so as a head of mission in societies undergoing rapid change, like South Africa, India, and China. I was a better public servant because of my academic training. This allowed me to see things and act on them in ways I otherwise would not have.

Additionally, I have become a better scholar due to my practical experience, which I can draw upon in both the classroom and my writing. However, it is essential to recognize that the transition between academia and diplomacy is not seamless. The skill sets required in each field are quite different, and unless one is willing to try to learn those skills, I would not recommend lightly making that transition. Mid-career, one must also be prepared to cope with uncertainty.

What is the most important advice you could give young International Relations scholars?

Finish your dissertation and publish it. If English is not your native language, do the needful to master it as if it were. IR scholars need to think big. Do not focus exclusively on writing articles for peer-reviewed journals read by a handful of colleagues. Write books as well. Big ideas require books, which is also the way to engage a broader public.