Written as events unfolded, this collection of articles, originally published on E-IR throughout the first half of 2011, offers insightful and diverse perspectives on the Arab uprisings, and expands to consider related political unrest outside the predominantly Arab world, such as in Iran.

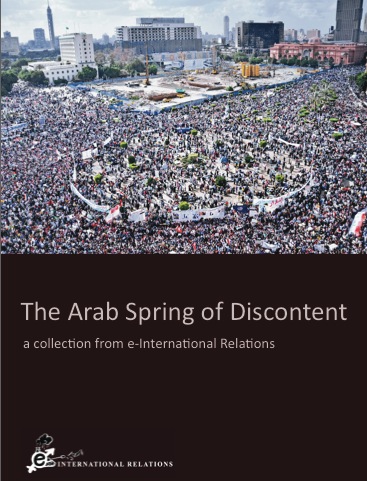

Click on the image below to download the collection as a pdf.

Introductory notes from the collection:

Introductory notes from the collection:

by Al McKay

On December 17, 2010, Muhammad Bouazizi, a 26-year-old street vendor, went to work in the provincial town of Sidi Bouzid, which lies in the centre of Tunisia. Bouazizi, a graduate who had struggled to find work, had taken to selling fruit and vegetables as a way of feeding his family, and putting his sister through university. Unfortunately, he had not acquired a licence to sell goods, and a policewoman confiscated his cart and produce. So Bouazizi, who had had a similar event happen to him before, attempted to pay the fine to the policewoman. In response, the policewoman slapped him, spat in his face and insulted his deceased father. Her actions were to have a lasting effect on him.

Feeling humiliated and infuriated, Bouazizi went to the provincial headquarters with the intent to lodge a complaint to local municipality officials. However, he was not granted an audience. At 11:30 am and only a few hours after his initial altercation with the policewoman, Bouazizi returned to the headquarters, doused himself in flammable liquid, which he had recently purchased, and proceeded to set himself alight.

The act itself was particularly brutal and Bouazizi subsequently died of the injuries he sustained, but it proved to be the spark from which greater forms of indignation would emerge. One man’s self- immolation appeared to encapsulate a pent up sense of frustration which had been buried deep down inside many young Tunisians concerning a broad scope of social issues. Violent demonstrations and riots erupted throughout Tunisia in protest of the high unemployment, corruption, food inflation and lack of many political freedoms. The intensity of the protests was such that it led to the then President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali stepping down on January 14, 2011. This was a remarkably sudden series of events. In just a matter of weeks, a regime, which had enjoyed 23 years in power, had been ousted by a campaign of popular pressure. However, this phenomenon did not remain confined to Tunisia’s boundaries.

The ruptures of the events in Tunisia seemed to echo elsewhere, the so-called “Tunisian wind” swept across North Africa and the Middle East, and began a great chain of unrest. Although events did not occur in an identical fashion to those witnessed in Tunisia, it seemed that people across the Arab world were actively taking the initiative to overthrow their autocratic governments. Modern technology played a part in this as social media websites such as Facebook and Twitter enabled the flames of discontent to be fanned and spread the news to an observing world.

To date, there has been a further revolution in Egypt; internal violence in Libya; major protests in Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Oman and Yemen; and comparatively minor protests in Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Western Sahara.

Not since the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the demise of the Soviet Union has change swept so suddenly across a geographical region. However, the initial voices of optimism are not as confident as they once were. What may have started as genuine endeavors by civilians to achieve social change have now become causes for concern. There is an anxiety that new despots will simply replace the former ones in many of these states. History has suggested that this could easily occur and it is not necessary to go back too far in time to locate examples. In 1979, the autocratic and domestically despised Iranian monarch, the Shah, was overthrown in a popular revolution, but was simply replaced by an extremist clerical dictatorship that consolidated absolute power in mere months, and holds it to this day. There are signs that many of the uprisings could follow in the same doomed footsteps.

In Tunisia, although tentative steps towards democracy have been made, there are serious concerns that the revolution is now being hijacked by politicians. More than 50 political parties have registered for the scheduled July elections, including some headed by well-known former members of the ruling party. Each of these groups may seek to fulfil their own personal ambitions rather than initiate policies for the collective good.

In Egypt, it seems that, for now, rule of the country still lies with the military rather than the people after Mubarak’s fall. There is also the risk that Islamism may start to have a stronger influence in the state, particularly from groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood, which has branches all over the region.

Egypt is not the only nation where Islamist messages are being whispered alongside the clamour of revolt. In Yemen, religious radicals are seeking to exploit anti-government protests against President Ali Abdullah Saleh, a U.S. ally against Al Qaeda.

In Syria, conservative Sunni Muslims, more antagonistic toward Israel than the President Bashar Assad, could fill the vacuum if his government is overthrown.

In spite of these sources of anxiety, Libya’s situation has attracted the most engagement from the West, where the extent of the civil war has caused a US- led intervention. A UN sanctioned no-fly zone has been established over the state, and air strikes have been conducted by British, US and French forces. If Gaddafi is overthrown, another power vacuum could open up in the nation.

Taking all of these developments into consideration, the central question of whether real long-term political change will occur in the Middle East and North Africa remains open, and perhaps only time will enable us to understand what shape these movements in the Arab world will take.

Nonetheless, these events have elicited a plethora of global interest from the media, policymakers and academics. E-International Relations has provided a platform for these voices to be heard. Written as events unfolded, this collection of articles offers insightful and diverse perspectives on the Arab uprising, and expands to consider related political unrest outside the predominantly Arab world, such as in Iran. This collection should be of considerable interest to students of international relations, particularly those with an interest in the politics of the Middle East and North Africa. It should also be of intrigue to those with an eagerness to examine the conceptual issues of social change, political protest and humanitarian intervention.

The collection begins with a trio of articles exploring the Tunisian revolution. Alyssa Alfano’s opening piece engages with one of the most interesting aspects of the revolution, the role of the internet in the mobilization of popular pressure against Ben Ali’s regime. Following this, Afshin Shahi contemplates the future of post-revolution Tunisia. This is an important area to venture into because questions have arisen concerning the direction of political life in the country, especially in regards to the role of the military in politics and the forthcoming elections. The third article acts as a significant addendum to a wider debate on the conceptual issue of revolutions. This contribution from Simon Hawkins considers the important question of whether the events in Tunisia can actually be understood as a revolution.

Contributing authors include:

Toby Jones, John Chalcraft, Ramesh Thakur, Jamsheed K. Choksy, Mary Ellen O’Connell, Simon Hawkins, Clive Jones and Francesco Cavatorta.