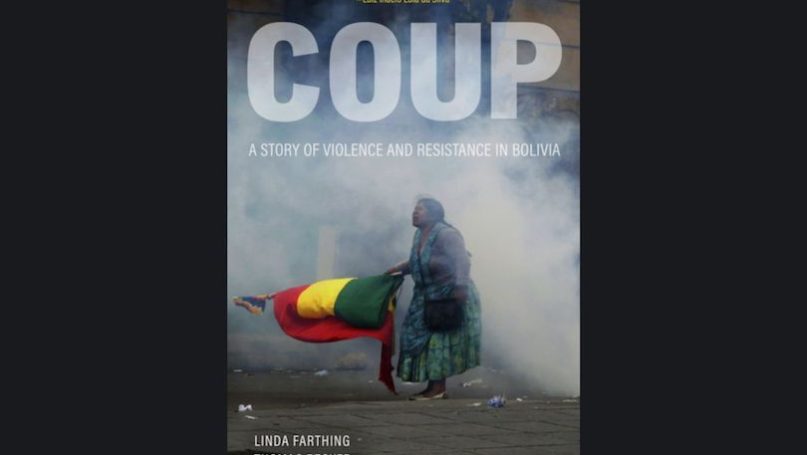

Coup: A Story of Violence and Resistance in Bolivia

By Thomas Becker and Linda Farthing

Haymarket Books, 2021

On 28 December 2022, the governor of the Department of Santa Cruz, Bolivia, Luis Fernando Camacho, was detained on charges of sedition and terrorism for his role in the toppling of Evo Morales in November 2019. What followed contained echoes of the events of 2019, as violent protestors burnt the district attorney’s office and Minister of Public Works Edgar Montaño’s house to the ground and attempted to ‘take’ the Departmental Police Command. A series of arson attacks against the district attorney’s infrastructure followed, with mass mobilisations and violence in the city of Santa Cruz and other departmental capitals continuing in the following weeks well into January 2023.

Reporting in the national Bolivian press has spoken of a ‘reactivation’ of violence in Santa Cruz, drawing a line through the events surrounding Camacho’s arrest and the political crisis of late 2019. The spark of these renewed tensions was the legal case, known as “Golpe de Estado I” (Coup D’état I), presented against Camacho and his political allies by former MAS senator Lidia Patty. Open wounds fester, and the need to grapple with the causes and consequences of the tumultuous period of Bolivian history in 2019 is, arguably, greater than ever. Doubly so given the talk of a second Pink Tide, a new generation of Leftist Latin American governments seeking to build on the legacy of Morales and his contemporaries.

These reasons alone are enough to recommend reading Linda Farthing and Thomas Becker’s recent book on this period, Coup: A Story of Violence and Resistance in Bolivia, published in 2021 by Haymarket Books. The endorsement of current Brazilian President, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva — a longtime ally of Morales during his first stint in power between 2002 and 2010 — suggests as much. However, the importance of Coup also lies in the careful and meticulous way the book was put together.

To begin with, the book offers a great introduction to the Bolivian context for the uninitiated reader. Here, Farthing and Becker’s longstanding commitment to the country shines through. Becker is a human rights lawyer who has worked in Bolivia for the last two decades, successfully bringing ex-President Sánchez de Lozada to justice for his part in the massacres of protesters in the city of El Alto during October 2003’s Gas War. Farthing has spent extensive periods in Bolivia and the brilliance of her previous books, co-authored with her late partner Benjamin Kohl, lay in their ability to present the reader with a clear picture of a particular aspect of the country without losing any of the nuances.

The same is true here, as Farthing and Becker situate Bolivia within the Pink Tide and present the reader with the wider causes of the political crisis of 2019. The two chapters in the middle of the book addressing the period of Morales’ government are on their own clear and concise introductions to the gains and limitations of his political project, and fantastic teaching tools for those leading undergraduate courses on modern Latin America, actually existing alternatives to neoliberalism, or the political economy of natural resource extraction.

Chapter two does an excellent job of separating the distinct historical threads that lead to the 2019 crisis. The reader is given short, sharp snapshots of the opposition; the election debacle in October 2019; the protests against Evo Morales; the resignation of Morales and the struggles that followed; and the role of the police and military in the crisis. The authors also, despite their decisive position on the issue, lay out the core arguments of the competing understandings of this moment: coup d’etat or fraud. This adds subtlety which often has been missing from much of the anglophone analysis of November 2019, many of which were quick to draw conclusions, not always for the rights reasons.

This being said, there are strong arguments for framing this moment as a coup, arguments that need to be laid out in the cold light of day given the continued vociferousness of the political debates in Bolivia around October-November 2019. Farthing and Becker use the testimonies of those caught up in the midst of the violence to make these arguments powerfully. They bring the human element of the coup to the fore. They show how often abstracted notions of racism, oppression and marginalisation shaped state violence and the massacres at Senkata, in El Alto, and Sacaba, the town in the coca-growing region of the Chapare, Cochabamba. In doing so, they also provide clear evidence of political persecution, abuse of state power and the degradation of the country’s already weak legal and political institutions.

If there is a shortcoming to the book, it lies in the limited national focus on events in Bolivia. The fall of Evo Morales sits in a wider arch of history, the last leader of the Pink Tide governments that governed large swathes of Latin America during the first two decades of the twenty-first century. The 2008 crisis, the resurgence of the Latin American Right, the global emergence of populism and the rise of China weigh heavily on this moment, as does the need to shift away from fossil fuels. Indeed, one of the things that foreign commentators got wrong was to draw a neat line between the struggles over who controls Bolivia’s lithium resources and the coup. Farthing and Becker could have fleshed out these international factors in connection with the domestic ones that dominate their analysis, especially given the intended international audience of the book — it is, after all, written in English and published in the United States. Nonetheless, these are minor blemishes, especially when one considers the tight turnaround time of the book and the treacherous waters the authors had to navigate. As we have already seen, the events of November 2019 continue to divide Bolivia in very violent terms.

In sum, Coup offers a clear and sharp picture of a complicated and confusing moment in Bolivian history — this book goes a long way to adding clarity to what actually happened and why. Critics will accuse the authors of pursuing a political agenda — the propagation of the coup narrative — from the outset. This, however, I feel is unfair for two important reasons. Firstly, the arguments and evidence for both sides of the debate are presented and analysed. It is from an assessment of history that the authors draw their conclusions. Secondly, as anyone who followed this moment of Bolivian history closely, the abuses of the government that followed Morales’ ousting — that of Jeanine Áñez — needed to be called out and shown to the wider world. As is nearly always the case in Bolivia, those who found themselves at the sharp end of the violence of late-2019, were the most historically marginalised communities in the country. Giving them a platform is as good a reason as any to take the position that Farthing and Becker assume. The space given to marginal voices in Coup makes it a powerful account of the political events of 2019 in Bolivia.