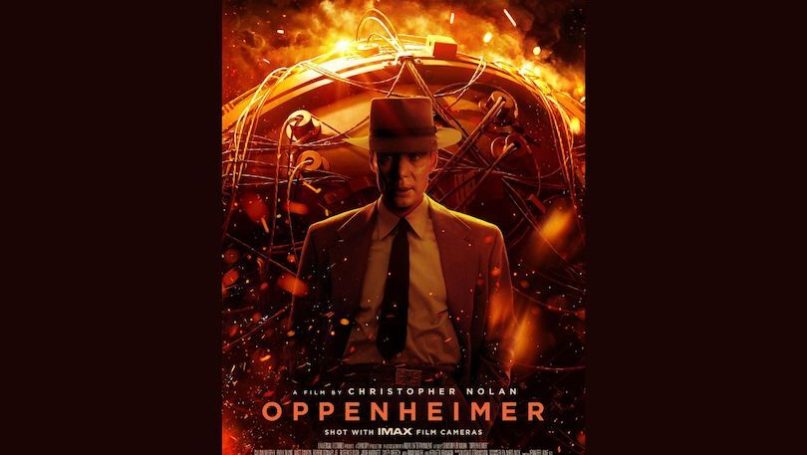

Oppenheimer

Directed by Christopher Nolan

Universal Pictures, 2023

Christopher Nolan’s delicately crafted film interpretation of Kai Bird’s American Prometheus, offers a mine of information for International Relations students. The subject matter – the development of the Atom Bomb – has been a chestnut of IR syllabi for half a century. The moral dilemmas, and international consequences of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, are brooding staples of every IR classroom discussion. Moreover, the world which followed, with the angst of the Cold War, and the threat of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) are recurrent themes in the global teaching of international affairs. In this important movie, Nolan dissects the contested legacy of Robert Oppenheimer (played by Cillian Murphy), as the ‘father of the atomic bomb’. In 1943, invited by General Leslie Groves (played by Matt Damon), Oppenheimer assumes directorship of the Los Alamos Laboratory, the Manhattan Project’s New Mexico site preparing an atomic bomb. As Nolan shows, Oppenheimer, initially, was driven by moral concerns. In regard to how he overcame his initial dilemma, as a Jewish man, he profoundly feared the outcomes if the Nazis were to develop a weapon of such deadly capability. That got him over the scholars’ initial moral reticence, and undoubtedly the younger Oppenheimer, like everyone else, was carried aloft by the frenzied pace of historical events.

However, following Hitler’s defeat, Oppenheimer still assisted with the bomb’s deployment in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, now believing it would swiftly terminate the grisly war in the Pacific, and (naively) the concept of war itself. As Nolan shows, the reluctant physicist became a convert to nuclear weaponry. Now we know that scholars have criticized the argument that the bombs precipitated Japan’s surrender. Some historians and IR experts suggest the real turning point was the threat of Soviet invasion. Certainly, as this movie shows, Oppenheimer’s utopian vision was challenged by fellow scientists like Edward Teller (played by Benny Safdie) and even by the chairman of the US Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis Strauss (played by Robert Downey Jr.), demanding an ever more destructive H-bomb. Predictably, this was grossly disproportionate to anything the world had ever seen – still less needed. Deterrence had quickly become a game of nuclear destructive power. This filled Oppenheimer with personal anguish and regret.

IR students will be able to see, subsequently, how these global issues played out against the self-destruction of a brilliant scientist, and the gruesome character assassination of his entire family circle. The big searchlights of the American security apparatus quickly beamed into the quiet scientist’s own home. Now, Oppenheimer opposed the subsequent nuclear arms race between the US and the Soviet Union. Predictably, he met the equally formidable weapon of American political oppression – namely anti-Communist hysteria. The Big State sought out Oppenheimer’s own skeletons. Oppenheimer soon fell victim to his personal links with the Communist Party, through alleged ‘Commy camp-followers’ such as his brother Frank (played by Dylan Arnold), wife Kitty (played by Emily Blunt), and ex-lover Jean Tatlock (played by Florence Pugh). There was a vast security file generated by state spooks drudging around peccadillos in the scientists’ personal life. This all wreaked formidable public humiliation for a character prone to psychosis and life-long mental health struggles.

IR instructors will marvel how well the film is deftly constructed to allow its audience to comprehend, on an intellectual level, the breakthrough that led its protagonist to see himself as the “Death, destroyer of worlds” of Hindu scripture. It provides excellent material for class discission about the moral debate on nuclear weapons as the film beautifully teases an unheard conversation between Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein (played by Tom Conti). The detonation of the A-bomb, during its first test in the New Mexico desert, exudes the primal force which led Oppenheimer to view himself as a kind of ‘American Prometheus’ (as in the 2005 biography Nolan draws on). Nolan’s A-bomb is wondrous, which reminds IR instructors that the Atom bomb was resolutely seen at the time as achievement more than nightmare. Thus, in Oppenheimer, a man’s private, internal, and political lives are overtly exposed, each a luminant component of the inherent contradiction which defines a man’s soul.

We also get a great sense of IR history from this movie. Chronological timelines are handled visually via the use of colour and black-and-white film. We are immersed in the Trinity tests and Second World War by brilliant colour, while in juxtaposition the post-war era is archival black-and-white. The prime event is the Trinity nuclear test in the New Mexico desert in July 1945, when Oppenheimer is said to have pondered (and later intoned) Vishnu’s lines from the Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”. Later in the 1950s, the movie revisits him as disillusioned, immiserated functionary, hounded by the McCarthyites for his communist connections. We are swiftly reminded that even the most momentous events of global history are ultimately (in genesis) someone’s painful private history. This, in turn, raises dilemmas for us as IR scholars, as to the mutual territories of private and public IR.

Perhaps the film’s crucial moment is its portrayal of the legendary postwar encounter in the White House Oval Office between Oppenheimer and President Harry Truman (played by Gary Oldman), who made the executive decision to drop the bomb. Nolan and Murphy hint that the inventor seeks absolution from the President, mumbling that he feels he has “blood on his hands”. Truman, in a rather priest-like gesture, immediately takes full responsibility as President and ponders: does Oppenheimer think the Japanese care who made the bomb? Thus as scholars of IR we see how private, internal and political lives interplay as destruction and hubris feed a relentless logic (literally) of a chain reaction.

French filmmaker, François Truffaut stated that “war films, even pacifist, even the best, willingly or not, glorify war and render it in some way attractive”. This may be why Nolan does not exhibit the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki so that we, as viewers, are spared our own dilemmas. We are transported delicately from the phantasmagorical prowess of Oppenheimer’s physics to the realization that the Cold War really started before World War II was over – it was always there, shaping the bizarre but ubiquitous paranoia of atom-bomb politics. We see Oppenheimer contra-indicated as the ruthless nuclear zealot and Oppenheimer as the mystic idealist fusing into one. And we see that the race to complete the Manhattan Project, in Los Alamos, New Mexico, proved conclusively that the nuclear age had arrived. This is IR history portrayed in one brilliant tableau for discussion.

Writing about Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Thomas Gaulkin offers key disclosures. First, the history of the Bulletin is inseparable from the history of the making of the nuclear bomb, not least because Oppenheimer himself was the first chair of the Bulletin’s Board of Sponsors. Many of the other key scientific figures depicted in the film served as early sponsors of the Bulletin, too (including Albert Einstein and Edward Teller). His second disclosure is that any inventor becomes incrementally less significant as time passes. However, world-changing the scientist, events seize their own power and shape their own course in IR history.

Oppenheimer, the movie, we must realize, is Nolan’s prismatic psychological study of one man’s human choices and struggles, not a history of the bomb. To that extent this movie can only offer a personal vignette. It is a mere sketch of the vast constantly evolving subject of nuclear weaponry in international relations. It is but a cameo-shot to a story which has its own indeterminate nuclear half-life and which has more primordial energy than any one human, even one as brilliant as Oppenheimer. This is a reminder of the grander tapestry of contemporary international relations.