As political dissent, human rights abuses and violent conflict spread, increasingly individuals are fleeing their homes in search of safety in other countries. Some countries establish clear and well-funded refugee resettlement programs. Others, either due to citizen pushback or government policy, have little tolerance for refugees seeking resettlement, actively discouraging arrivals. With the 13th largest nominal GDP, South Korea can afford to resettle refugees, yet faces a largely unsympathetic public. We ask why South Koreans are so opposed to accepting refugees.

Although South Korea has not hosted large numbers of refugees historically, this changed in 2016 when the number of Yemeni asylum seekers rapidly increased. While this was primarily isolated to Jeju island, this generated significant conservative and Islamophobic backlash state-wide. Previous research found African asylum seekers similarly faced logistical challenges in gaining refugee status in South Korea, despite their small numbers. Limited survey work however suggests that while there may be an anti-Muslim bias, the public was generally unwelcoming of refugees regardless of origin. Previous survey work also suggests a hesitancy to encourage immigration, with indifference even to many groups of ethnic Koreans abroad.

South Korea remains a mostly homogenous population, with a foreign population of a mere 3.1% of the whole population, with most of the immigrants actually coming from China. Of that, 72% of the Chinese immigrants are ethnic Koreans. In fact, 43% of all foreigners in South Korea are ethnic Koreans returning back to the peninsula now that the state is a stable democracy. South Koreans are even taught in elementary school about their “ethnically homogenous” society and talks about a “homogenous Korean population”, which could attribute to the anti-immigration sentiment amongst South Koreans that also includes anti-refugee sentiment.

To determine the extent to which South Koreans are opposed to accepting refugees, we sought to understand how the presentation of accepting refugees influences support. For example, South Koreans may not be aware of how few refugees resettle in their country and may only know of high-profile instances such as the Yemeni case. Likewise, South Korea falls well under rates of other economically developed countries, although they are alone in this regard in the region, where Japan frequently accepted only dozens a year, peaking at 202 in 2022, and Taiwan continues to lack an asylum law.

To address this, we conducted a national web survey September 27-October 11 of 1,300 South Koreans via quota sampling on gender, age, and region, administered via the survey company Macromill Embrain.

We randomly assigned responses to one of four questions about refugees:

V1: Should South Korea accept more refugees?

V2: South Korea typically has accepted only a few hundred refugees a year. Should South Korea accept more refugees?

V3: South Korea has typically only accepted about 1.5% of refugee applications, lower than most other developed countries. Should Korea accept more refugees?

V4: South Korea typically accepts only a few hundred refugees a year and only accepts about 1.5% of refugee applications, lower than most other developed countries. Should South Korea accept more refugees?

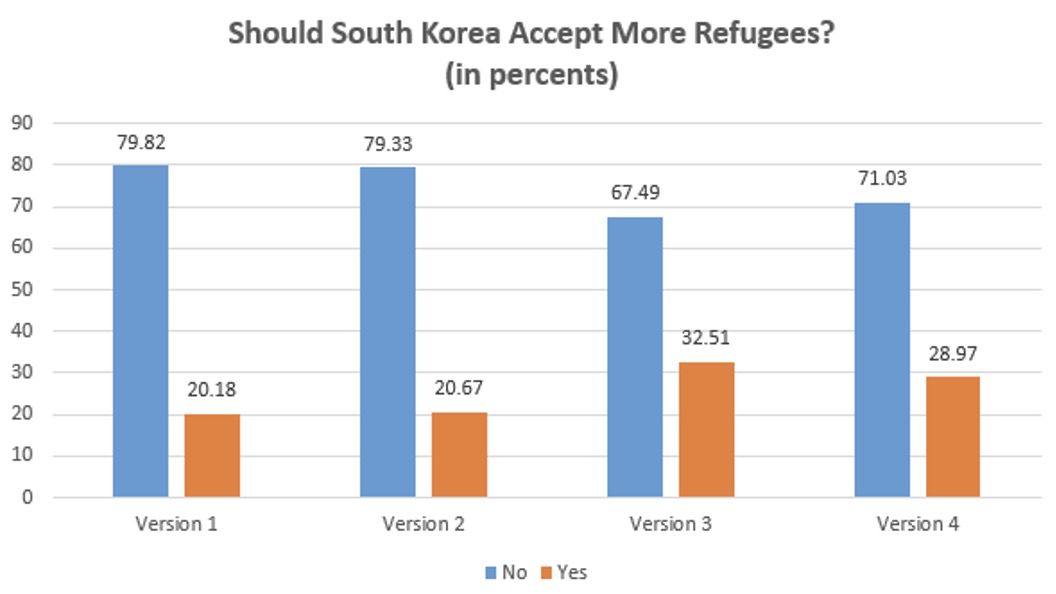

Across all four versions (see Figure 1), we find broad opposition to accepting more refugees. However, we find evidence that the wording of our question influenced the response. The baseline, “Should South Korea accept more refugees” received overwhelming opposition at nearly 80% saying “No.” Mentioning how few refugees are accepted in raw numbers (V2) produced no statistical change from the baseline version (V1).

However, when we included a statement that said the percentage of refugee applications accepted in South Korea was lower than most developed countries (V3 and V4), we found increased support by roughly 8%-12%. Broken down by party identification, we see similar evidence of how word choice influences support. Support across each version is higher among the liberal Democratic Party (DP) compared to the conservative People Power Party (PPP), but this peaks in V3-V4 at about 40 percent.

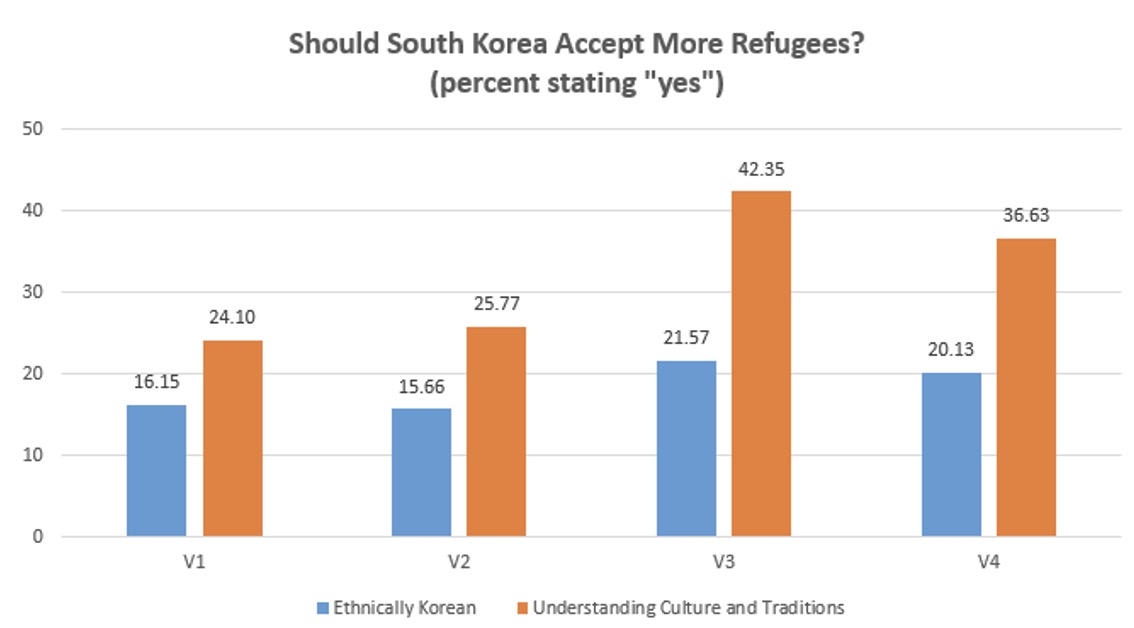

Also in the survey, we asked which of the following factors was more important in defining an individual as “Korean”: being ethnically Korean or understanding Korean culture and traditions. Here (see Figure 2) we find a publicly nearly evenly split (48.38% vs. 51.62%), with clear differences on partisanship and age cohorts. Assuming that those who do not define Korean identity on ethnic lines would be more supportive of refugees, below we show support for each group based on experimental version received. Consistently those who define being Korean as cultural understanding were more supportive of refugees. Moreover, we see the same pattern here as before, with greater support under V3 and V4, and with those not defining identity on ethnic lines clearly more sensitive to the wording.

Taken as a whole, the results suggest not only generational changes that may lead to a gradually more acceptant environment for refugees, but also that proponents may wish to play upon pride in South Korea’s economic development and how this creates expectations for state behavior similar to expectations of international aid assistance.

South Korea might also be forced into accepting more refugees soon as the state has a domestic labor crisis due to their low birth-rate and aging population. South Korea is the only country in the world with a birth-rate below 1.0, reaching an all-time low of .78 in 2023. Currently, 25.7% of South Koreans are over the age of 60 and 60% of those aged 55-75 have returned to the workforce to help curb the impending shortage. Once South Korea’s economy starts to take a fall due to this, politicians and the public may be more welcoming to refugee resettlement.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Funding for this survey was provided by the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS) as well as the Mahurin Honors College at Western Kentucky University.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – South Koreans Support Unification, But Do They Support Integration?

- Opinion – Would You Hire A North Korean? South Korean Public Opinion is Mixed

- Surveying Opinion on Withdrawing US Troops from Afghanistan and South Korea

- Surveying the American Public on the Plight of Climate Refugees

- Opinion – Japan-South Korea Relations: Breaking the Cycle?

- Legal Representation for Asylum-Seekers and Refugees: Much Needed yet Sparse