This case study is an excerpt from McGlinchey, Stephen. 2022. Foundations of International Relations (London: Bloomsbury).

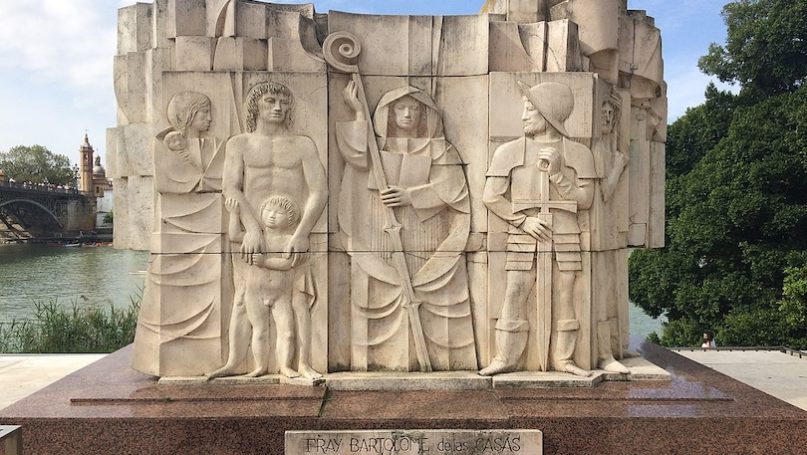

Bartolomé de las Casas (1484–1566) was a Dominican Friar, the first resident Bishop of Chiapas (in present day Mexico), and first official ‘Protector of the Indios’. Las Casas became an influential scribe. It is from Las Casas’ copies of the original that Christopher Columbus’s diaries are known to us today. Las Casas also provided a damning account of Spanish colonisation in the new world. But before any of this, Las Casas arrived with his father in Hispaniola (present day Haiti and Dominican Republic) with the first wave of Spanish settlers. On the island, Las Casas benefitted from the Encomienda system which enabled settlers to expropriate lands from the Taino peoples while at the same time placing them under a brutal labour regime. In 1510 Las Casas was ordained a priest, the first such ordination in the Americas. But this did not stop him from taking part in the violent conquering of the neighbouring island now known as Cuba.

In 1515 Las Casas had a spiritual awakening. From here on, he would wage war on two fronts: a) to save the indigenous peoples from extermination; and b) to save the souls of Spanish settlers from damnation due to their acts (Wynter 1984). Late in his life, back in Spain, Las Casas joined in an influential debate with Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda organised by the church to evaluate the treatment of indigenous peoples in the Spanish empire. This debate happened in the city of Valladolid in 1950–51, where Columbus was buried. The Valladolid debate provides a different perspective on the issue of rights than those found today. Rights in modern-day International Relations are primarily debated with regards to the legal and normative frameworks of global governance, which was introduced in the prior chapter and will be expanded upon in later chapters. Most influentially, some in International Relations have looked towards ‘scaling up’ domestic laws to the global level. In contrast, the Valladolid debate was not concerned with scaling up a domestic issue. The debate began with an issue that was already globally inscribed in the mapping out of Spain’s imperial expansion. The key ethical question arose from discovery and conquest: who was sufficiently ‘human’ to afford the natural protections provided by God to his highest creations?

Sepúlveda argued that indigenous peoples across the Atlantic, the ‘Indios’, were by nature slaves who were ‘deficient in reason’ – a result of their geographical location to the West andSouth that made them weak. Sepúlveda drew upon the established hierarchies of humanity that had been mobilised to justify European-Christendom’s holy wars. Las Casas disagreed, and he did so by critically re-reading the Christian sources and arguments that Sepúlveda drew upon.

We can unpack the logic of Las Casas’s argument from his Apologetic History of the Indies (no date). When it came to the claim that inhabitants of the tropics (the ‘torrid’ zone) were less-than-human, Las Casas argued that God could not have been so ‘careless’ when he made such an immense number of ‘rational souls’. In fact, Las Casas followed Columbus in arguing that the tropical climate of the Caribbean actually enjoyed a ‘favorable influence of the heavens’ leading to a ‘healthfulness of the lands, towns and local winds’. Just as importantly, Las Casas drew on the ambiguities that surrounded the Canary Island natives. Turning to Aristotle’s influential description of what counted as a ‘barbarian’, Las Casas pointed out that not all barbarians lacked reason. They could simply be ‘offspring of people who have not yet been saved by Christ.’ Moreover, Las Casas argued, even if they did not know Christ, the Indios still exhibited collective virtues that were lacking in the conquistadors and were perhaps greater developed than in the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome. In other words, native Indios were eminently equipped with the character and disposition to receive Christ and thus become good Christians.

Overall, Las Casas departed from Sepúlveda by challenging one of the key tenets of Christian cartography at the time, namely, that climate produced a hierarchy of humans. Instead, he claimed that it was possible for humans to exhibit reason wherever they were ‘found’ under the heavens. What truly mattered was whether indigenous peoples demonstrated the dispositions that would enable a peaceful conversion to Christianity and thus inclusion into the only human family that really mattered.

There is one more element to Las Casas’s criticism of conquest that deserves mention. While he was committed to opposing the hierarchy of humanity proposed by the model of different climatic zones, for much of his life, Las Casas found less urgency in contesting the way in which the so-called sins of Ham found their way into this model. In 1516, Las Casas suggested that, in order to alleviate the suffering of native Indios, the Spanish crown could replace those bonded under the Encomienda system with ‘20 negroes or other slaves for the mines’. As late as 1543, Las Casas was advocating for replacement of the slave-population: Africans for native Indios. By the time of the Valladolid debate Las Casas had experienced a second awakening, albeit almost 40 years after his first revelation in Cuba. He now judged African enslavement to be ‘every bit as unjust as that of the Indios’, and that it was not right that ‘blacks be brought in so Indios could be freed’ (Clayton 2009). One should not fault Las Casas’ final position on discovery and conquest. Nevertheless, the subject of the Valladolid debate was the treatment of Indios and not Africans. In this respect, Las Casas’s early defence of native Indios was never fully integrated with his later defence of African peoples. Not even Las Casas arrived at a fully inclusive conception of the ‘human’.

Thus, the Valladolid debate was not primarily about rights – domestic or international – but more fundamentally a question of humanity. Specifically, who was sufficiently competent to exercise their humanity so as to be protected by natural rights. The debate turned on the extent to which and the means by which an already geographically diffused and diverse humanity could (or could not) be converted to the one true religion: peaceful and consensual, or violent and coercive (see Blaney and Inayatullah 2004).

Paradoxically, the Valladolid debates reflect the logic behind many recent justifications for humanitarian intervention to protect people from harm – such with the Responsibility to Protect. When it comes to such humanitarian action, the political question is usually over who has the authority to determine that one principle – non-intervention – should be put aside for the preservation of another principle – protection. The Valladolid debates suggest that this humanitarian question has always been answered by those who wish to intervene ascribing to themselves a moral superiority over those who they wish to protect. While such justifications do not reference religious affiliation, they are nonetheless predicated upon the age-old idea that there are ‘saviours’ who have the right (or the duty) to save ‘victims’ who must accept that help or be classified as unruly and disorderly (see Mutua 2001). In other words, debates over humanitarian intervention still operate with a similar logic to debates over discovery and conquest: humanity is hierarchically ordered rather than equally created.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Discovery, Conquest and Colonialism

- The First Continental Conference on Five Hundred Years of Indigenous Resistance

- Student Feature – Theory in Action: Indigenous Perspectives and the Buffalo Treaty

- International Security

- Student Feature – Theory in Action: Critical Geography and Inuit Views

- Poststructuralism