This case study is an excerpt from McGlinchey, Stephen. 2022. Foundations of International Relations (London: Bloomsbury).

One of the most challenging issues facing our global environmental governance model is the predominance of a specific state, the United States, in the international discourse and global policy arena. The United States, reflecting its disproportionally influential position globally, has used that influence to drive international environmental politics in some arenas over recent decades. Yet, it has also been inconsistent – or perhaps even negligent – in others. This issue is compounded by the fact that the United States (second to China) is the world’s second largest emitter of the greenhouse gasses that drive climate change. It is important to realise the risks in such a situation where one state is so influential – especially if the internal politics of that state should shift and its leadership become absent. Indeed, this allows us to also consider effects not just at the state level, but to consider the impact of one individual, Donald Trump, and his preferences on shaping global climate progress during his four-year term in office.

There is no question that a state leader with a strong personality can have an impact on global politics (see De Pryck and Gemenne 2017). Charisma, personality, wisdom, intelligence and being able to articulate a vision are all individual traits that can drive the way in which a message is passed on. For example, the joint announcement of then-US President, Barack Obama, and Chinese Premier, Xi Jinping, in September 2015 that they would both formally join the Paris Agreement was emblematic of the power of charisma and leadership gravitas to push the agreement over the line and secure the support of other more reluctant states. Nevertheless, individual personalities are not the only domestic sources of influence in international environmental politics. There are hundreds, perhaps even thousands of participants in global negotiations around every single environmental issue, from marine protected areas to international travel of hazardous waste, from climate change to biodiversity to bio-accumulable chemicals.

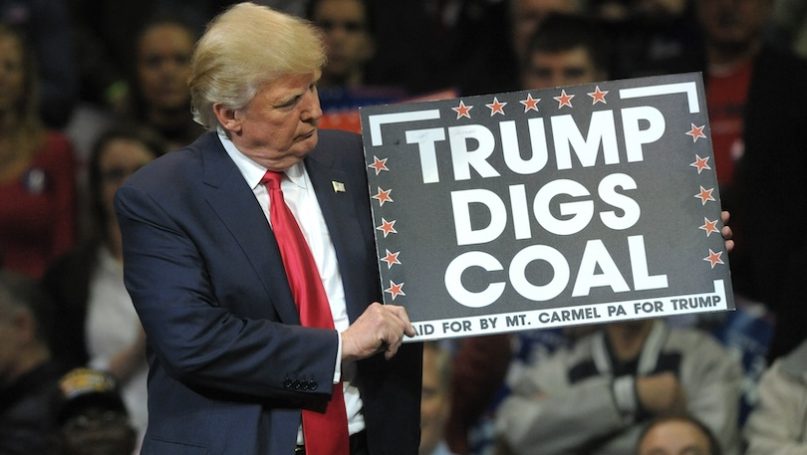

One of the reasons why Trump has had so much influence on global climate politics is because he unilaterally chose to leave the Paris Agreement and effectively terminate all substantive participation by the United States of America in global climate negotiations (see MacNeil and Paterson 2020). In doing so, Trump manifested an environmental sceptic’s view, meaning that he did not seem to believe that climate change was worth his attention, or his state’s actions. Environmental sceptics typically believe that any kind of collective concern about the impacts of industrial and human activities on ecosystems’ health is overhyped or is a hoax by scientists and politicans. In line with this, Trump tweeted in 2012 that ‘the concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make US manufacturing non-competitive.’ A range of other tweets and statements pointed to his lack of belief that climate change is driven by human activity, is widely exaggerated by scientists, and that mitigating it is not worth the costs. Trump also actively worked to undermine the regulatory role of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) within the United States arguing that such domestic agencies have a negative impact on business by producing too much regulation (commonly known as ‘red tape’).

Applying Trump’s personal views more broadly within the phenomenon, climate sceptics (or deniers), do not believe the scientific consensus on climate change. Some do not believe it is occurring at all due to a misunderstanding between local weather and global climate (pointing to instances of cold winters for example) while others believe that it is occurring but is not driven by human activity. What most sceptics have in common is a rejection of attempts to change human and industrial behaviour. In addition to denial over the science, such global mandates also raise legitimacy issues at the political level for such thinkers as they tend to come from ideological positions that reject the authority of international agreements or organisations – seeing such attempts as tyrannical or illegitimate. Climate scepticism is therefore a cultural issue, more than just a political one (See Dunlap et al. 2016; and Hoffman 2011).

Clearly then, Trump is just one voice in an established discourse. This discourse is especially prevalent in the United States and the Republican Party where such thinking has become mainstream. Yet, because of the place of the United States in the global system, the unique ways that Trump wielded his executive power, and his unique mastery of the media – Trump has had an undeniable effect on global discourse around climate change policy negotiations. When we are confronted with such a strong political polarisation and a strong domestic opposition to a global norm, as well as a powerful leader with a counterpoint view of the issue, a countervailing process emerges. This can be seen as follows: the counter-norm of climate scepticism works against the global consensus. In this case, that global consensus was the one agreed in 2015, including with the backing of the United States. Considering this from a normative framework, Trump’s reversal was not just a domestic policy shift. Due to his unique impact, his actions have effectively mainstreamed climate denialism – something that was already well established before his election, but operating at a peripheral level. Recalling the norm lifecycle first explored in chapter seven, Trump’s example does not mean that climate denialism is so globally diffused that it has countered the already existing norm supporting international cooperation towards global climate change action and emissions reductions (see Matthews 2015). For example, it took several decades, and multiple acrimonious diplomatic encounters for the consensus of 2015 to be reached. We will have to wait for more time to pass to see the extent to which Trump’s singular actions diffuse through the global system, but the International Relations’ toolkit gives us the means to track this. If Trump’s actions cause a cascade and become internalised, resulting in other states coming to follow his example, then any future of global climate agreement is certainly going to be materially different, if it exists at all. This will be measurable beyond his presidency, as is has already been established that these views do not originate with Trump, but rather that he mainstreamed them. Yet, it seems that few other global leaders have followed Trump’s example. And, following Trump’s defeat in the 2020 presidential election the successor Biden administration swiftly re-joined the Paris Agreement.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Greta Thunberg and Climate Activism

- Student Feature – Theory in Action: Global South Perspectives on Development

- The Trump Administration’s Withdrawal from the JCPOA

- Environment and Climate

- Russia’s Internet Research Agency and Cyberwarfare

- Student Feature – Theory in Action: Green Theory and Climate Change