This January, President Trump referred to North Korea as a “nuclear power”, with then Secretary of State nominee Pete Hegseth stating the same, prompting concerns from South Korea. These statements suggest a future in which, rather than promoting denuclearization, the US recognizes North Korea’s nuclear program and instead focuses on limiting the further production of weapons. Such a policy may be consistent with North Korea’s own goals, as the country in January described itself as a “responsible nuclear state” at a UN disarmament conference. We then ask: how does the American public view North Korea’s nuclear weapons?

North Korea began their pursuit of nuclear weapons in the 1960s, when they coordinated with the Soviet Union on developing missile technology. However, Kim Il Sung’s request for nuclear weapons was only answered with nuclear energy technology assistance. North Korea continued to pursue nuclear weapons despite initially ratifying the Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1985 and signing the Joint Declaration regarding a non-nuclear Korean peninsula in 1992, ultimately pulling out of the NPT in 2002. In 2006, North Korea conducted its first nuclear test, while under Kim Jong Un (2011-), North Korea has conducted four nuclear tests and tested three times more missiles than his father and grandfather combined.

North Korea is assumed to have around 50 nuclear warheads, although some estimates put it closer to 90, and the capabilities to roughly double that amount based on available fissile material. Increasingly longer-range missile tests now suggest the capability of hitting nearly anywhere in the US, although this does not ensure North Korea second strike capabilities. Likewise, the success of even one nuclear weapon hitting South Korea would be devastating. In 2022, the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) adopted a law that broadens the scope in which North Korea can use their nuclear weapons, and in 2023 added language to their constitution about their nuclear weapons. Kim Jong Un has further stated that he is dedicated to varying their nuclear stockpile and expanding production “exponentially”.

Most experts suggest that the regime views these weapons in terms of enhancing defensive capabilities, deterring potential invasions without the necessity of matching traditional military capabilities. However, if the regime sees their options as increasingly limited, diplomacy may lose out to greater willingness to consider offensive use. Kim Jong Un himself stated the weapons were not just for defensive measures. Others argue that the nuclear capabilities themselves are not the problem, but how a nuclear North Korea alters traditional alliances.

Understanding American public opinion here is crucial for several reasons. A public particularly concerned about North Korea’s nuclear weapons may lead policymakers to take a more aggressive stance towards the country, regardless of whether this might worsen the problem. How the public views this threat also has ramifications for the US-South Korea alliance, and particularly the continuation of US bases in-country. Meanwhile, a public that views North Korea’s program as primarily defensive in nature is unlikely to demand denuclearization, opening the door potentially for a shift towards limiting the number of nuclear weapons.

Survey data consistently shows Americans view North Korea as a critical challenge, although direct questions about their nuclear program are less common. More than three quarters of Gallup respondents from 2003-2019 evaluate the country unfavorably. A 2016 YouGov survey found 14% of respondents considered North Korea an immediate and serious threat to the US, with another 42% calling the country a somewhat serious threat. Only 7% considered the country not to be a threat. Pew Research Center surveys in 2013 and 2017 find an American public that increasingly believes North Korea is capable and willing to use nuclear weapons against the US, with 65% of respondents in 2017 stating they were very concerned about North Korea having nuclear weapons. However, according to Gallup data from 2001-2019, North Korea was only seen as the greatest threat to the US in only one year: 2018. Survey data from 2020-2024 also shows few Americans feel North Korea should be able to maintain its nuclear weapons, with rates similar to Pakistan, and well below views of the same weapons from China and Russia.

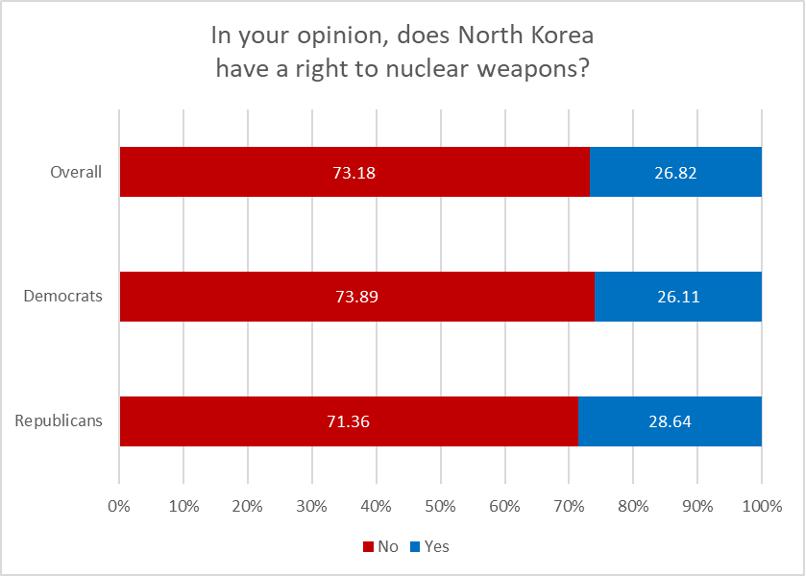

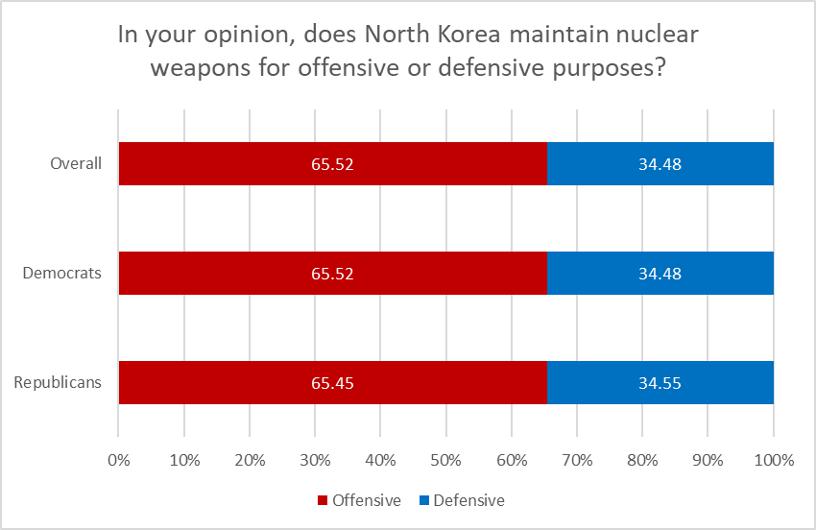

To address this public sentiment, we commissioned a web survey through Centiment February 12-26. We asked 522 respondents two interrelated questions: (1) In your opinion, does North Korea have the right to nuclear weapons? And (2) In your opinion, does North Korea maintain nuclear weapons for offensive or defensive purposes? (see figures 1 and 2). The first would aim to address whether the respondents view North Korea as having the right that any sovereign state would have to choose a nuclear arsenal or whether, either due to beliefs about the weapons in general or North Korea specifically, that they should be excluded from the category of recognized nuclear states. The second taps into how North Korea’s nuclear weapons are assessed.

We find nearly three-quarters (73.18%) state North Korea does not have a right to weapons, with marginal difference between Democrats (73.89%) and Republicans (71.36%). Likewise, nearly two-thirds state the country’s weapons are for offensive purposes (65.52%), with no substantive difference on partisan lines. Moreover, views are highly correlated: those who believe North Korea has a right to these weapons are slightly more likely to view the weapons as defensive in nature (50.71%), while those who deny North Korea this right overwhelmingly view the weapons as offensive (71.47%).

We would assume views would also be shaped not only but pre-existing beliefs about North Korea, but also how well informed one might feel about the country. Earlier in the survey we asked respondents to evaluate North Korea, among several countries, on a five-point scale (1=very negative, 5 =very positive). We find that preexisting views unsurprisingly shapes views with those with negative views of the country (1-2), which comprised three-quarters of respondents, stating the country did not have a right nuclear weapons (79.03%), while 67.92% of those with a positive view of the country (3-4) stating they had a right to the weapons.

Likewise, those already viewing the country negatively viewed their weapons as offensive in nature (70.08%), compared to only 39.62% of respondents with a positive view. We measured how well informed one thought they were about North Korea on a four-point scale (not informed at all to very informed). Here only 21.26% of low informed respondents believed North Korea had a right to nuclear weapons, increasing to 37.93% among the more informed. However, in both groups, only 34.48% believed the nuclear program was for defensive purposes.

Our findings indicate an American public that largely rejects North Korea’s right to nuclear weapons and perceives its program as offensive in nature. The results may indicate a public that either no longer sees the norm against nuclear use as absolute or misunderstands the strategic calculations behind North Korea’s nuclear policy. While expert consensus holds that North Korea’s stockpile is fundamentally about deterrence, the public’s perception of an offensive posture could shape policy debates in ways that encourage more confrontational strategies rather than diplomatic engagement.

In addition, the strong opposition to recognizing North Korea as a nuclear state, including those who felt more informed, suggests that American views are deeply entrenched and this rigidity may limit a Trump administration’s flexibility in pursuing arms control measures short of full denuclearization, despite growing acknowledgment that North Korea is unlikely to ever relinquish these weapons. If North Korea conducts another nuclear test, public concern may intensify further, preventing pragmatic engagement.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Trump’s ‘Personalised’ North Korea Policy: 2018–2020 and the Way Forward

- Opinion – North Korea’s Nuclear Tests and Potential Human Rights Violations

- The Danger of Passive Containment and Ignoring North Korea

- Opinion – Would You Hire A North Korean? South Korean Public Opinion is Mixed

- Opinion – The US Doesn’t Need More Nuclear Weapons

- Reflecting on a Career Researching Climate Change and Security in North Korea