This essay will discuss ‘collective memory’ in the contexts of the Holocaust and the genocide in Rwanda. There are connections between these contexts that will be analysed, such as the iconography of Holocaust images, which is projected onto images of the genocide in Rwanda. It will be argued that the hegemony of Holocaust atrocity stipulating in the West, and the victimisation that has followed it, have made it harder for certain narratives and images to be seen as legitimate without being considered anti-Semitic. I will discuss this in relation to an art installation called ‘Snow White And The Madness of Truth’ by artists Dror Feiler and Gunilla Sköld Feiler (2004). There is also a hegemonic construction of collective memory in Rwanda. Any questioning of the current Tutsi government, and any discussion of the atrocities committed by them toward refugee Hutus in the Democratic Republic of Congo, is seen as a questioning of the narrative of the genocide against the Tutsis. It will be argued that these hegemonic narratives of collective memory are strongly enforced by atrocity images, which evoke similar visual representations from the Holocaust. These narratives are to an extent exploited in order to silence narratives that would contribute to a more inclusive fuller account of historic events. I will refer to Judith Butler (2009) to argue that these conditions of victimisation dictate which lives are considered more grievable than other lives.

Susan Sontag argues that ‘What is called collective memory is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds.’ (2003: 76). The activity of collective remembering, which is inseparable from power relations (Gillis 1994), is then according to Sontag a demanding of the importance of one narrative over another. It could also be explained as a hegemonic discourse that is used in relation to certain historic events. Sontag (2003) also points out that individual memory is not reproducible and that this is the only type of memory there is. Collective memory is, therefore, a type of oxymoron. It is not a valid term in a literal sense. It can, however, be used providing that we understand its constructed character. It is, however, subjective and serves particular ideological positions (Gillis 1994). Since collective memories are social constructs, who does the stipulating? The hegemonic discourse, utilised to talk about certain events, could be said to stipulate the narrative to be told. What this discourse is depends on the historical situation and on the event in question. Sontag (2003) suggests that pictures, linked to a specific story, are a crucial part of this stipulating that is collective memory. Frances Guerin and Roger Hallas (2007) are discussing the witnessing of events through images and visual culture. They argue that images can reinforce textual discourses but that we increasingly also question their truth value (Guerin and Hallas 2007: 2).

However, viewing images of atrocities have become almost conventional occurrences and this has arguably resulted in us noticing the images less (Zelizer 1998). Barbie Zelizer (1998: 216) argues that there is a ‘response of habituation toward contemporary atrocities’. She points to that some of the reasons for this are diminished political and moral need to see images of atrocity as well as a diminished trust in their truth value (Zalizer 1998) We have sometimes even arrived at the point when there is a saturation of atrocity images to the extent that they have become iconic. Sontag (2003) points out that photographs of genocide have undergone an institutional development and that there is a recirculation of iconic photographs. Public spaces, such as Holocaust museums, have been created for them to ensure that the crimes depicted stay in peoples’ consciousness and continue to be remembered (Sontag 2003). However, this memorialising through atrocity images can also have contributed to the habituation concerning them, even if this is not the intention. By continuing to keep these photographs in public circulation they become more of iconic artworks and less of atrocity documentation.

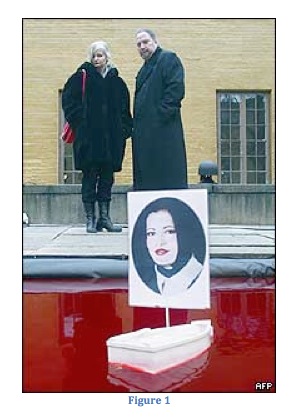

A representation that could be seen as going against the norms of remembering is the art installation ‘Snow White and the Madness of Truth’ by Dror Feiler and Gunilla Sköld Feiler (see: www.bbc.co.uk). The installation made for the exhibition ‘Making Differences’ in Stockholm in conjunction with a conference about genocide. In the artwork, the picture of the female Palestinian suicide bomber Hanadi Jaradat, who killed 21 Israeli civilians in a bombing attack in 2004, was presented on a miniature boat floating on top of a pool of red liquid that was made to look like blood (see: Figure 1). The narrative of Jaradat’s life was written on a wall by the installation. The work was supposed to illustrate how violence breeds violence and show the circumstances behind this act, which was the death of her brother by the Israeli army. However, the Israeli ambassador in Sweden, Zvi Mazel, took offence and sabotaged it by throwing the lights in the pool. He interpreted the artwork as anti-Semitic and as a call to genocide and received support for his actions from the Israeli Prime Minister, at the time, Ariel Sharon (see: www.artcrimes.net). The artists have also been threatened repeatedly. I am mentioning this event to argue that there are many ways of remembering traumatic events and one way can even be to in a way memorialise the perpetrator without justifying their actions. It needs to be mentioned that Dror Feiler is himself Jewish and is a member of the organisation Jews for Israeli Palestinian Peace (see: www.jipf.nu). This installation reflected on the larger context the circumstances around actions as well as displaying the complexity of the story behind this act. What was especially interesting about this incident is that it seemed to be the picture of the suicide bomber that created such a strong reaction from the Israeli ambassador and others. Instead of seeing the image through the context in which it was put, floating on a pool of blood which is not an especially flattering material to float around on top of (Rosenberg 2004), the ambassador saw it as a glorification of the suicide bomber in question (see: www.artcrimes.net).

Judith Butler (2004) argues that to charge people who hold critical views with, for example, terrorist-sympathising and anti-Semitism creates an environment of fear in which voicing certain views is to risk being branded with a stigmatising identification. Narratives, and especially images, of the Holocaust and the anti-Semitism tied to it have created strong collective memories and connotations. Because of this, the memory of this victimisation can easily be exploited in order to suppress critical opinions regarding later political developments, such as the one in Israel/Palestine. Butler (2004: 102) is questioning the view that engaging in critique against Israel amounts to ‘effective anti-Semitism’. She points out that ‘historically we are now in the position in which Jews cannot be understood always and only as presumptive victims’ (Butler 2004: 103). In other words, the victimisation of Jews and Jewish suffering should not be used as a tool to suppress political critique of Israel. In the context of Jewish criticism of Israel, as in the case with Dror Feiler, Butler goes on to say that ‘though the critique is often portrayed as insensitive to Jewish suffering, in the past and in the present, its ethic is wrought precisely from that experience of suffering’ (2004: 103).

There is a quiet agreement of what are the most important historic events without a questioning of why some events are constructed as more important than others. This idea is closely connected to ‘who’ is important which determines what values we give to different events. Goldberg asks ‘Why do we recognise the death or disappearance of some, of those we deem ‘our own’ individually and collectively, more so, more readily than others?…we more readily commemorate their contribution to our social lives. What brings them closer, elevates them, sanctifies them? Jewish suffering we are exhorted never to forget.’ (Goldberg 2006: 347). The availability of photographic evidence for the stories of the Holocaust could be one reason for why this suffering is elevated and more recognised than other collective sufferings. The commemoration of the Holocaust is being reproduced through the photographs and we rely ‘increasingly on visual memory to help us make sense of the past and present’ (Zelizer 1998: 202). Beyond this, and maybe sometimes because of this, there are also norms dictating what lives are recognised as more grievable than others (Butler 2009).

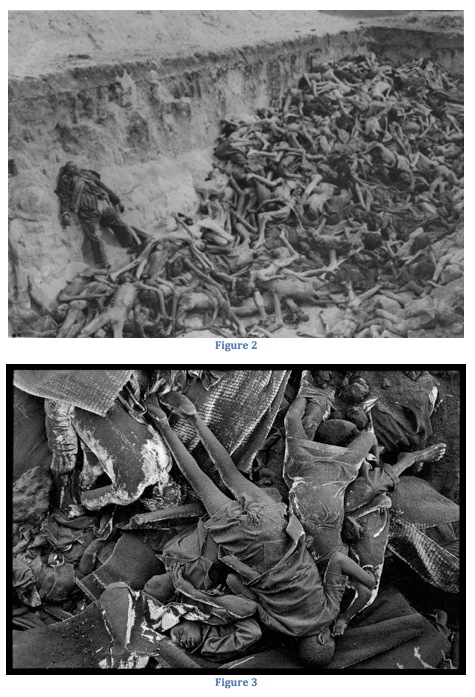

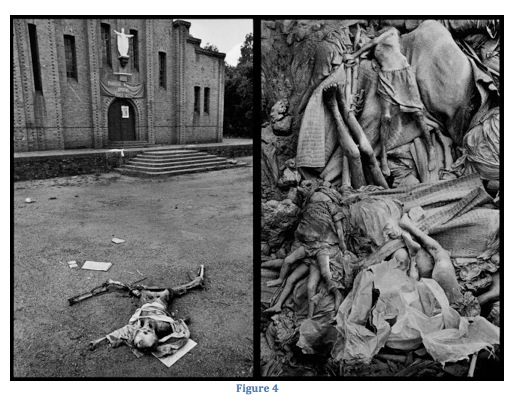

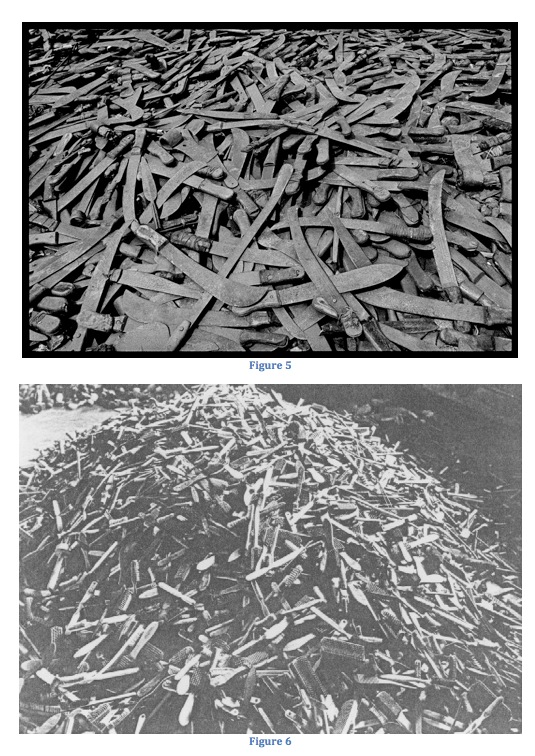

Guerin and Hallas (2007) argue that traumatic events, such as the Holocaust, are unrepresentable through images and that images are not able to show the full reality of those events. This can lead to images becoming simplified symbols of atrocity. The argument can be taken further by looking at how the ‘reality’ depicted in images of the genocide in Rwanda have been interpreted through Western discourses about the Holocaust. These interpretations have often failed to see the larger historical narratives behind the atrocities. Photographs from the Holocaust are among the ones that Sontag (2003) refers to as photographs recognised by everyone, which are an important part of what society has chosen to think about. Photographs such as Figure 2, which shows a mass grave after camp liberation in Bergen-Belsen in Germany in 1945 (see: www.ushmm.org) is one of the many representations of the Holocaust. They are so much a part of western collective memory that photographs like the one by photographer James Nachtwey, of the aftermath to the Rwandan genocide (see: Figure 3) make us recall images of the Holocaust in Europe. However, this picture is not from Rwanda but instead from Zaire. It shows a mass grave made for the many Hutu refugees who died from a cholera epidemic in the refugee camps (Nachtwey 2011). It is clear how easy it can be to misinterpret this image for depicting bodies of Tutsis who were murdered during the genocide. That is the dominant story about the genocide just as the narrative about the murdering of Jews is the dominant one about the Holocaust. This misinterpretation is easy to make since in this article there are pictures of killed Tutsis next to a picture of a mass grave in Zaire (see: Figure 4). Zelizer (1998) argues that contemporary atrocity photographs are presented without information about what is being depicted and with a generalised sense of horror instead of a detailed account of the instance. The article by Nachtwey does narrate an account of what the photographs are actually showing. However, whether intended or not, the dominant story, which is that of the genocide of Tutsis, tends to be what we relate the atrocity images to.

Holocaust pictures, and especially those depicting the fate of the Jews, have somehow become the ‘universal’ symbols for the Holocaust and have the function of a ‘genocidal imaginary’ (Torchin 2007: 91). In other words, the images determine how pictures of other genocides are interpreted. As Leshu Torchin (2007) argues, other genocides are understood and produced through the interpretive frame provided by images of the Holocaust. In collective memory work about the Holocaust, pictures ‘lock the story in our minds’ (Sontag 2003: 76). Zelizer says that it has become the archetypal case of genocide and that the Holocaust has been used as ‘a metaphor for tragedy’ (1998: 174). Torchin (2007: 92) is discussing ‘Holocaust iconography’ in relation to the Armenian genocide and says that visual evidence of the latter is being ‘filtered through a lens of acknowledged genocide’. Rwandan genocide photographs can be discussed in a similar way. Claudia Koonz (1994: 260) points out that ‘historical memorialisation depends upon the interpretation of a signifier…that stands between the viewer and the event commemorated; once a powerful icon enters into circulation, its connotations are set in motion’. The connotations given to Holocaust images can in a way move on to other images so that the collective memory of this historical event is being projected onto later events. There are aesthetic parallels between Holocaust pictures and images of contemporary atrocities, to the extent that Holocaust photos linger in the images of the Rwandan genocide (Zelizer 1998: 220). A very clear example of an aesthetic parallel is the one in the photographs in Figure 5 and 6. The first photograph, taken by Nachtwey, is of a pile of machetes that were used during the genocide and left behind when the Hutus, who committed the genocide, fled the country (Nachtwey 2011). The second photograph is depicting hairbrushes of Holocaust victims found in Auschwitz, Poland after liberation (see: ushmm.org). The large number of items piled up, in both of these pictures, signifies the enormous amount of lives lost in both of these genocides. Despite the very different nature of the items depicted, the images have the same effect on the viewer, which is to contemplate on the sheer number of lives that were ended in such a systematic manner. They even conjure up images of mass graves and piles of bodies. It is useful to use Barthes (1972: 114) notion of ‘myth’ as a ‘second-order semiological system’ in order to analyse the aesthetic connection between these pictures. In the first picture the sign is what becomes of the image of the machetes (the signifier) and the lives lost (the signified). This sign, in turn, becomes the signifier for an underlying myth of genocide, which has its origin in Holocaust images such as the one in Figure 6. This shows how powerful the collective memory of the Holocaust is in the West. Zelizer (1998) argues that, because of this, we may need to remember earlier atrocities less so that we can remember contemporary ones more.

Sontag (2003) points out that for many people, who are anti-war, images of war are generic and the victims are anonymous. This could explain why Holocaust iconography is used as a kind of template for images of other genocides. In this way pictures tend to simplify the narrative behind them. Holocaust images and narratives also give an impression that there is a clear-cut distinction between the perpetrators and the victims. Since the main narrative about the Rwandan genocide is that Tutsis were the victims and Hutus the offenders, this is what tends to linger in our memory about the event. The pictures also seem to lock this narrative in our minds and most of the nuances and alternative narratives are never shown to us.

A narrative concerning the Rwandan genocide, which is not talked about much, is the one of atrocities committed against Hutus. The Rwandan Patriotic Front, which formed the current government in Rwanda, has committed atrocities against Hutus such as the killings in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which the UN has called possible genocide (McGreal et al 2010). René Lemarchand and Maurice Niwese says that the regime have been imposing an official memory which ‘rules out a recognition of the ambivalence of the notion of guilt’ (2007: 167). Thus, in the case of Rwanda there emerges yet another hegemonic simplified victimisation of one group of people. This victimisation leaves no room for complex narratives and nuanced historic explanations of relations between Hutus and Tutsis. Explanations that involve colonialisms influence and race thinking, which divided Hutus and Tutsis and introduced ethnic identities as stable which was not the case before colonialism (Prunier 1995). As Sontag (2003: 76) points out, ‘there is no such thing as collective memory…But there is collective instruction’. Symbols in the form of certain historic events, such as atrocities and genocide, can reinforce and legitimate this instruction and photographs are a convincing way of memorialising these symbols.

Relating to Stuart J. Kaufman’s (2001) Symbolic Politics Theory, the genocide could, and arguably has, become a symbol that creates and sustains a myth of victimisation and legitimises oppression. This can apply to both Holocaust victimisation of the Jews and Tutsi victimisation. The circumstances are of course very different between these examples. However, showing how they have both been historically created and sustained through a myth of victimisation can give a broad view of how symbolic politics works. The oppression, which is legitimated through this victimisation in Rwanda, could create further self-victimisation by Hutus and could lead to a new crisis. This is why ‘the implications for reconciliation strategies go beyond the simplistic notion that revealing the truth will bring about peace and harmony…What is to be remembered, by whom and for what purpose – these are the critical issues that need to be addressed’ (Lemarchand and Niwese 2007: 168). This is said in relation to the reconciliation work in Rwanda after the genocide. The whole truth is not always revealed and there often seems to be a selection of what truths should be paid attention to most. Zelizer argues that ‘our often empty claims to memory work render us capable of little more than remembering so that we can forget in its shadow’ (1998: 202). The Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda focuses on genocidal acts, and other international humanitarian law violations, within Rwanda during the year of 1994 (see: www.unictr.org). This is a limited view of the truth and the concern is that a certain part of the population (the Hutus) are criminalised, because of high civilian participation in killings (Straus 2007: 124-125), while violations against Hutu refugees will go historically unnoticed.

Recognition is a salient word in this discussion since collective memory requires the recognition of certain events or lives over others. Butler (2009) argues that there is a distinction between apprehending and recognising a life. She says that there are ‘categories, conventions and norms that prepare or establish a subject for recognition’ (Butler 2009: 5). She is referring to the Western norm of what it is to be human and to what lives are recognised as grievable within this norm (Butler 2009). However, this can apply to many historical situations. The victimisation of Jews, tied to the Holocaust, and of Tutsis in Rwanda after the genocide are not permanent conditions. This is made clear by the fact that Hutus were seen as the victims of oppression before the end of colonialism since Tutsis were, originally, racially favoured by the colonisers (Prunier 1995). However, even if not permanent, these conditions of victimisation dictate which lives are considered more grievable than others at any one time.

Butler says that ‘The fact of enormous suffering does not warrant revenge or legitimate violence, but must be mobilised in the service of a politics that seeks to diminish suffering universally, that seeks to recognise the sanctity of life, of all lives’ (2004: 104). A recognising of all lives, even the life of a suicide bomber, motivated the political intention behind ‘Snow White and the Madness of Truth’. However, trying to represent and problematise the narrative behind an atrocious act, without condoning the act in itself, is often met with resistance. It is this simplified type of discourse that Butler (2004) is discussing in the context of 9/11. She says ‘It is that date and the unexpected and fully terrible experience of violence that propels the narrative’ (Butler 2004: 5). But by not recognising the many different narratives that take place before, after and during events like these we risk reproducing the violence that we claim to oppose.

This essay has argued that what is called collective memory depends on the existence and upholding of hegemonic discourses that in these contexts create conditions of victimisation. It has been argued further that pictures play an important role in the creating and upholding of these conditions. Pictures often simplify events and narratives to the extent that we might misinterpret them. It has been argued that Holocaust pictures have, at least in the West, served as a template for images of other genocides. By analysing pictures from Rwanda next to Holocaust pictures it is evident that some of the myths of visual atrocity images are re-represented in contemporary genocide photographs. Alternative or additional narratives are usually not shown. It has also been argued that it is difficult to represent other narratives because of a discourse that stigmatises whoever do. The example of ‘Snow White and the Madness of truth’ is a case in point. The displaying of this work rightly represents the circumstances behind this bombing and at least attempts to create an imagination of all lives as grievable.

Bibliography:

Barthes, R. (1972), Mythologies, New York: Hill and Wang.

Butler, J. (2009), Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?, London: Verso.

Butler, J. (2004), Precarious Life: the Powers of Mourning and Violence, London; New York: Verso.

Feiler, D. and Feiler, G. S. (2004), ‘Snow White and the Madness of Truth’, Art Installation, Stockholm.

Gillis, J. R. (ed.) (1994), Commemorations: the Politics of National Identity, Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Goldberg, T. (2006), ‘Racial Europeanization’, Ethnic and Racial Studies 29(2): 331-364.

Guerin, F. and Hallas, R. (eds) (2007), The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory and Visual Culture, London; New York: Wallflower Press.

Kaufman, S. J. (2001), Modern hatreds: the symbolic politics of ethnic war, New York: Cornell University Press.

Koonz, C. (1994), ‘Between Memory and Oblivion: Concentration Camps in German Memory’, in J. R. Gillis (ed.), Commemorations: the Politics of National Identity, Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Lemarchand, R. and Niwese, M. (2007), ‘Mass Murder, the Politics of Memory and Post-Genocide Reconstruction: the Cases of Rwanda and Burundi’, in B. Pouligny et al. (eds), After mass crime: rebuilding states and communities, Tokyo; New York: United Nations University Press.

McGreal, C. et al (2010), ‘Leaked UN Report Accuses Rwanda of Possible Genocide in Congo’, The Guardian, [Online], Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/aug/26/un-report-rwanda-congo-hutus, [Accessed 17.04.2011].

Nachtwey, J. (2011), When the World Turned its Back: James Nachtwey’s Reflections on the Rwandan Genocide, [Online], Available at: http://lightbox.time.com/2011/04/06/when-the-world-turned-its-back-james-nachtweys-reflections-on-the-rwandan-genocide/#1, [Accessed: 20:04:11].

Prunier, G. (1995), The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide, London: Hurst & Company.

Rosenberg, G. (2004), ‘Ambassadören Utnyttjar Antisemitismens Fobier’, Dagens Nyheter, [Online], Available at: http://www.dn.se/kultur-noje/ambassadoren-utnyttjar-antisemitismens-fobier, [Accessed: 27.04.11].

Sontag, S. (2003), Regarding the Pain of Others, New York: Picador.

Straus, S. (2007), ‘Origins and aftermaths: the dynamics of genocide in Rwanda and their post-crime implications’, in B. Pouligny et al (eds), After mass crime: rebuilding states and communities, Tokyo; New York: United Nations University Press.

Torchin, L. (2007), ‘Since We Forgot: Remembrance and Recognition of the Armenian Genocide in Virtual Archives’, in F. Guerin and R. Hallas (eds), The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory and Visual Culture, London; New York: Wallflower Press.

Zelizer, B. (1998), Remembering to Forget: Holocaust Memory Through the Camera’s Eye, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

http://www.jipf.nu/, [Accessed: 18.04.11].

http://www.artcrimes.net/snow-white-and-madness-truth, [Accessed: 18.04.11].

http://www.unictr.org/AboutICTR/GeneralInformation/tabid/101/Default.aspx, [Accessed 15.04.11].

Photographs:

Figure 1: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/3406745.stm, [Accessed: 19.04.11].

Figure 2: http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/media_ph.php?MediaId=695, [Accessed: 19.04.11].

Figure 3: http://lightbox.time.com/2011/04/06/when-the-world-turned-its-back-james-nachtweys-reflections-on-the-rwandan-genocide/#14, [Accessed: 20.04.11].

Figure 4: http://lightbox.time.com/2011/04/06/when-the-world-turned-its-back-james-nachtweys-reflections-on-the-rwandan-genocide/#9, [Accessed: 20.04.11].

Figure 5: http://lightbox.time.com/2011/04/06/when-the-world-turned-its-back-james-nachtweys-reflections-on-the-rwandan-genocide/#3, [Accessed: 20.04.11].

Figure 6: http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/media_ph.php?MediaId=645, [Accessed: 20.04.11].

Written by: Rebecka Tagt

Written at: Goldsmiths, University of London

Written for: Bernadette Buckley

Date written: April 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Traumatic Memory and Historical Narratives

- Does Presentism Work? An Evaluation of the Memory Politics of Fidesz

- Pax Kigali: Reconciliation and Peace in Contemporary Rwanda

- Accepting the Unacceptable: Christian Churches and the 1994 Rwandan Genocide

- Performances of Justice? Interrogating Post-genocide Adjudication

- The Cambodian Genocide: Operationalizing Violence Through Ideology