According to Amnesty International (AI), as of February 2010, only 58 states retain the death penalty in practice. In the past 25 years 67 states have abolished capital punishment for all crimes, 5 have abolished it for ordinary crimes, and a further 35 states have become de facto abolitionists[1] (Amnesty International, 2010). This trend is curious because abolition has met with significant domestic resistance in a significant number of abolitionist states, indeed, in many the majority were against abolition. IR Constructivists would argue that this abolitionist trend can be explained by the influence of a global abolitionist norm. However, this norm is by no means universally accepted. In 2008, at least 2,390 were executed in 25 states, and at least 8,864 people were sentenced to death in a further 27 states (Amnesty International, 2010). Since 1980, despite the global abolitionist trend, the number of executions in the United States, for instance, has increased significantly (Bae, 2007).

The Constructivist research agenda in IR places much weight on the influence that international norms wield over state policy. The activities of transnational advocacy networks and the ‘teaching’ effect of International Organisations are alleged to have brought about global policy convergence in issue areas previously accepted to be matters of national sovereignty. However, the empirical focus on norms and policy convergence is overwhelming on positive cases i.e. norms leading to policy convergence. Comparatively little scholarly attention is devoted to the negative cases where the link between norm and policy is absent, or where the mechanisms of norm transmission have failed to induce policy convergence. This selection bias towards ‘successful’ cases and the inadequate attention to the ‘dogs that don’t bark’ can have serious implications (Legro, 1997). By restricting their analysis to positive cases, constructivists can only make a solid claim that norms are necessary for policy convergence. Only by looking at negative cases, where the norm exists and actors propagate it but with no resulting convergence, can any claim for the sufficiency of norms for policy convergence[2].

In this essay, I do not mean to attempt to determine the necessary conditions for norm compliance. Rather, I suggest that claims concerning norms and policy convergence should not be applied overly deterministically. I intend to explore the emergence of the abolitionist norm and some of the factors that may explain the variation in compliance. Principally, I suggest explanations on the basis of evidence drawn from Europe, South Africa and the United States of America.

*

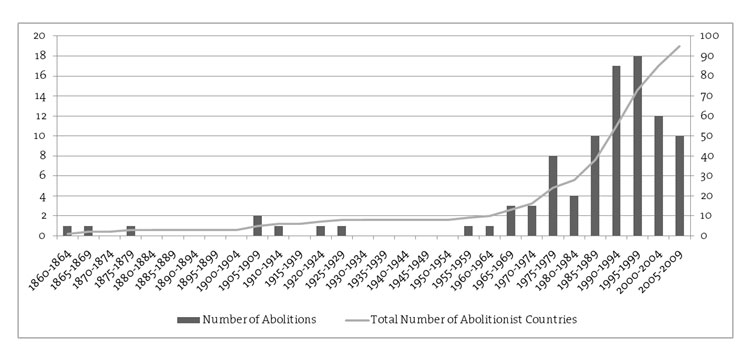

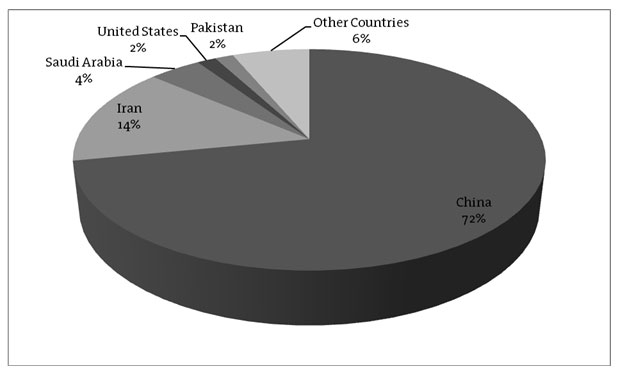

The death penalty is undeniably becoming less popular. Figure 1 demonstrates that ever more countries have abolished the death penalty. In general, abolishment is a recent phenomenon, 70 per cent of the 95 abolitionists (for all crimes) have abolished in the last 25 years (Amnesty International, 2010). In 1985, 17.2 percent of the world’s states had abolished the death penalty for all crimes, whereas 72.8 percent had statutes for its use for ordinary crimes. In 2000, by contrast, 38 percent of states were abolitionist for all crimes whereas 55.2 percent had statues for ordinary crimes (Anckar, 2004). Since 2000, as figure 1 demonstrates, the number of abolitionists has grown further still. Furthermore, in addition to the 95 complete abolitionists, a further 9 countries have abolished the death penalty for all ordinary crimes, and Amnesty (2010) regard a further 35 states to be de facto abolitionists. Indeed, the actual use of capital punishment within retentionist states, in general, has declined, and the vast majority of executions are undertaken by only a handful of states. In 2008, for instance, only 25 states carried out executions, five of which, China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and the United States of America (see figure 4) accounted for 93 per cent of all executions (ibid.).

As capital punishment is a domestic policy, the temptation is to look for an explanation of the abolitionist trend in ‘the domestic’[3]. Some studies (e.g. Anckar, 2004; Neumayer, 2008) link the abolitionist trends to trends in democracy, in particular, to the newly democratised states of the ‘third wave’. Rather than anything in inherent to procedural democracy, the explanatory variable is the alleged regard for ‘human rights’ in-built in the ‘democratic culture’ that accompanies a transition to democracy. Meanwhile, Badinter (2004) argues that there is an “indissoluble link between dictatorship and death penalty”, because it is “the ultimate expression of the power that the rulers wield over their subjects” (p. 11). Retention and use of the death penalty is far more prevalent in authoritarian states than in democratic states[4] but the transition to democracy cannot account for abolitionist trends.

Firstly, democratisation waves occurred previously without the emergence of any significant trends in abolition. It has taken a long time for many democracies to become abolitionist, and a significant of number of democracies (most notably the USA and Japan, and to a lesser extent India) continues to use the death penalty. Secondly, there is nothing abolitionist per se in democracy as a structure for collective decision making. On the contrary, if put to referendum one might expect the death penalty to be reinstated/retained owing to the tendency of popular opinion, even in democracies, to be pro death penalty[5]. For example, polling at the time of abolition in Britain (1998) indicated that as much as 70 per cent of the British people were in favour of the death penalty (Fawn, 2001). Even in Sweden, (abolitionist in 1972) where capital punishment was last used in 1921 and politicians of all stripes condemn its use, polling indicate that no fewer than 33 percent of the population is in favour of the death penalty[6] (Anckar, 2004). Indeed, the death penalty was reintroduced[7] by the democratically elected government of Guatemala largely as a result of the popular opinion[8] (Fawn, 2001). Thirdly, if there is some truth in the tendency of ‘democratic cultures’ to be pro-human rights in nature, then as abolition is a recent phenomenon, there must have been a qualitative change in the prevailing norms constituting the ‘democratic cultures’ of certain democratic states. Therefore, democratisation, and implicitly concern for the domestic interests of the state[9], cannot satisfactorily account for the abolitionist trend. Indeed, it appears as though a normative change may be behind any correlation between democracy and the abolition of the death penalty.

*

The abolition of the death penalty has become an international norm[10]. Calls for the abolition of the death penalty form part of the agenda of transnational human rights advocacy networks[11], but more importantly opposition to the death penalty has been institutionalised in four international treaties opposing the use of death penalty.

The ‘Second Optional Protocol to the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty’ adopted by UN General Assembly resolution 44/128 on 15 December 1989, declared that “no one within the jurisdiction of a State Party to the present Protocol shall be executed” (Article 1.1) and that “each State Party shall take all necessary measures to abolish the death penalty within its jurisdiction” (Article 1.2)[12] (U.N. Secretariat, 2006, p. 53). Similarly, Article 1 of both Protocol 6 (1983) and Protocol 13 (2002) of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of the Council of Europe (CoE) reads, “The death penalty shall be abolished. No-one shall be condemned to such penalty or executed.” [13] (Council of Europe, 1983, 2002) And, finally, Article 1 of The Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty (1990) of the Organisation of American States reads, “The States Parties to this Protocol shall not apply the death penalty in their territory to any person subject to their jurisdiction.” (Organization of American States, 1990)[14]

The abolitionist norm also appears to be evident in the form of changing public opinion. In 2007, a UN General Assembly resolution calling for all retentionist states to establish a moratorium on executions was passed by a vote of 104 to 54. Although not legally binding, this resolution, backed by a majority of countries, is indicative of changing international opinion. Indeed, the death penalty finds no place in the emerging architecture of international justice. Lifetime imprisonment was not only the maximum penalty on the statutes of the special tribunals set up by the United Nations Security Council to adjudicate crimes in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, but also the maximum penalty imposed by the International Criminal Court (Bae, 2007).

The abolitionist norm is most evident in Europe. Since June 1996 when the CoE made the immediate moratorium of the death penalty, and the ratification of Protocol 6 within three years, requisites for membership, abolition has taken on the appearance of a regime, i.e. a set “of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules, and decision- making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area”[15] among the member states of the CoE (Krasner, 1983, p. 2; Manners, 2002). The principles of the obligation regime are that, “everyone’s right to life is a basic value… and that the abolition of the death penalty is essential for the protection of this right and for the full recognition of the inherent dignity of all human beings.” (Council of Europe, 2002) The norm is the obligation of member actors abolish the death penalty, on which the rules of membership are based; and decision-making occurs in the inter-governmental organisational structure of the CoE. Indeed, the CoE make the claim that rejection of the death penalty has become “one of the cornerstones of European identity and one of the continent’s universal values”(Council of Europe Press Service, 2001, cited in Bae, 2007, p. 25).

The above changes representative of normative change seems to suggest that the abolition of capital punishment has gained a “kind of universal moral consensus”, and that it is no longer acceptable to defend retention on the grounds of religious/cultural relativism or national sovereignty (Ravaud & Trechsel, 1999, p. 89; Toscano, 1999). There has been a tendency in the literature (e.g. Bae, 2007), to generate strong universal claims regarding the existence and prospects of the abolitionist norm. In reality, this norm is by no means ‘globally’ or ‘universally’ accepted (Katzenstein, 2006).

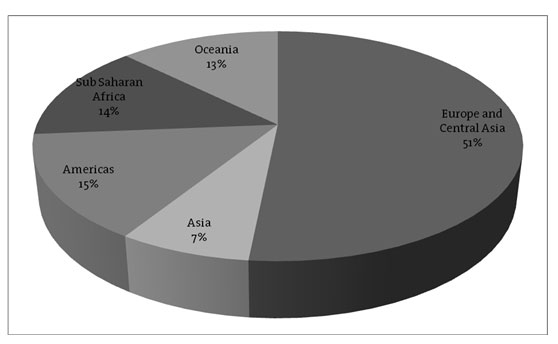

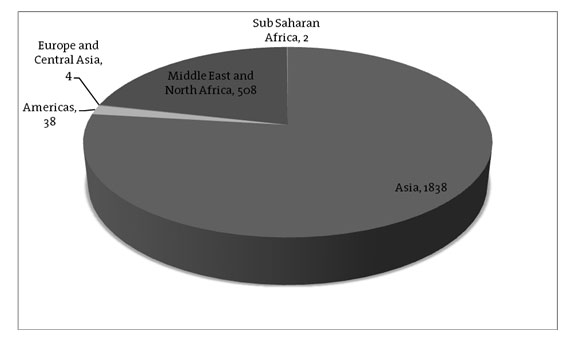

The acceptance of the abolitionist norm is limited and localised. Half of all abolitionists are European or Central Asian states (see figure 2), and capital punishment continues to be a very significant phenomenon in Asia and the Middle East (figure 3). Outside of Europe there has been limited legal change as a result of any abolitionist norm, made evident by the relatively poor rates of ratification for non-European international treaties on abolishing the death penalty (see Table 1). In 2008, at least 2,390 people were executed in 25 states, and at least 8,864 people were sentenced to death in a further 27 (Amnesty International, 2010). In some respects, this phenomenon is highly concentrated because, as previously mentioned, five states account for 93 per cent of all executions (figure 4). However, it is important to remember that (as of 2003) 57 percent of the world’s population lived in countries where the death penalty was still used (Truskett, 2003). Finally, the acceptance of the norm is not evident in much of the discourse of norm ‘rejecters.’[16] Indeed, rejecters question whether the death penalty even constitutes a violation of human rights, and as such, whether it even belongs in human rights discourse[17]. Despite these qualifications, the question of why any given state does, or does not, comply, with this international, albeit regional, norm remains interesting. To understand compliance it is first necessary to understand how norms function and spread.

*

Finnemore & Sikkink (1998) explain the influence of global norms in terms of a three stage ‘life cycle’ of norm emergence, norm cascade and norm internalization. The first stage is ‘norm’ emergence, in which, “norm entrepreneurs attempt to convince a critical mass of states (norm leaders) to embrace new norms” (p. 895). Norm entrepreneurs call attention to existing issues or ‘create’ new issues by a use of “language that names, interprets and, and dramatizes” them (p. 897). In terms of human rights norms, these norm entrepreneurs are typically ‘transnational advocacy networks’[18] which draw attention to existing issues, or help to ‘create’ new issues and categories via ‘framing[19]’ (Keck & Sikkink, 1999). Their fundamental objective is to change understandings of appropriate behaviour. Amnesty International and the CoE[20] are prominent members of the transnational advocacy network for the abolition of the death penalty. The former expanded its mandate to include opposition to the death penalty in 1973 and they have continued to maintain an active campaign since 1977 (Amnesty International, 2010; Rabben, 2002). In the 1970s there was little recognition of capital punishment as a ‘human rights issue’ at the intergovernmental level, but since then abolition has become a key part of the human rights agendas of a number of intergovernmental organisations (Rodio & Schmitz, forthcoming). These actors typify the ‘norm entrepreneurs’, persuading states[21] to change their policies, that characterise the first stage of the life cycle. Little normative change occurs without significant domestic movements supporting policy change, until a ‘critical mass’ of states adopt a norm. After the tipping point formed by this critical mass, a different dynamic begins as the norm enters the second phase of its life cycle[22] (Finnemore & Sikkink, 1998).

The second stage, norm cascade, is “characterised more by a dynamic of imitation as the norm leaders [states] attempt to socialize other states to become norm followers” (ibid., p. 895). In the context of international politics, “socialization involves diplomatic praise or censure, either bilateral or multilateral, which is reinforced by material sanctions and incentives.” (p. 902) Norm compliance in this second stage occurs in response to the institutionalisation of the norm, and the process of socialisation, which takes on the appearance of ‘peer pressure’ between countries (Finnemore & Sikkink, 1998). Socialisation, however, does not just occur between states, norm entrepreneurs continue to play a role as agents of socialisation by pressuring actors to adopt new policies and ratify treaties, and by monitoring compliance with international treaties (ibid.). Keck & Sikkink (1999) explain how the less powerful actors of transnational advocacy networks (in comparison to states) wield “information politics”[23], “symbolic politics”[24], “leverage politics”[25] and “accountability politics”[26] which can be used to persuade/compel states to comply with human rights norms (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 95). Socialisation appears definitely to have been a decisive factor in the engendering the European death penalty free zone. The degree to which all regions of the world have reached this second phase of the norm cycle is, however, questionable. (I address the possible factors that may explain why states respond, or fail to respond, to this ‘peer pressure’ below.)

The third stage is ‘norm internalization’ whereupon “norms take on a taken-for-granted quality and are no longer a matter of broad public debate” (p. 895). In this phase norms have been adopted to such an extent that adherence becomes habit, or to use Hopf’s (2002) terminology subject to the ‘logic of unthinkability’. Norms are, thus rendered uncontroversial and hence do not form the centrepiece of political debate. The abolitionist norm appears to have become internalised and in most Western European states, at least, it does not form part of political debate. However, gauging by the data on public opinion noted above, it appears as if the norm has only become internalised significantly in the minds of the political elite. Hence, the death penalty does not feature in political discourse, not because of popular acceptance of the norm, but rather elite acceptance.

*

Norms constrain behaviour because they are intimately connected with the sense of Self, indeed, it is through norms that meaningful understandings of the social world are formed. In a world devoid of intrinsic meaning, “our…dominant ways of thinking and acting in the world will be reproduced as ‘reality’” (Zalewski, 1996, p. 351). This means that identities, not only serve to categorise people, states and events according to common features, but they also represent attempts to render the chaos and strangeness of the entire (known) social world intelligible. The identities of states, therefore, emerge from the fundamental need of state elites to understand. An understanding of the state’s identity acts like an “axis of interpretation” that “conventionalizes” the objects the state encounters. Identities “simplify and homogenize by making the unfamiliar familiar in terms of the identity of the Self” (Hopf, 2002, pp. 5-6; Moscovici, 1988).

The key concern for this study is why the norm of abolition, despite increasing compliance, continues to be rejected by states that one might expect to be abolitionist. The abolitionist norm is unlike most other human rights norms, in that public opinion is largely pro-death penalty. Keck & Sikkink (1998) argue that “issues involving harm to populations perceived as vulnerable or innocent are more likely to lead to effective transnational campaigns than other kinds of issues.” (p. 99) As convicted criminals are rarely perceived as ‘innocent’, it makes campaigning for abolition of the death penalty one of the more difficult forms of human rights campaigning. However, this is not sufficient to explain why states do not comply with the abolitionist norm, when other states do.

The most obvious reason that states would reject norms is that compliance is not in the ‘national interest’. The Realist tradition, with its suspicion of the prospects for interstate cooperation, has one explanation for why compliance is not in the interests of states. For Realists, anarchy is the timeless and unalterable reality of the international realm; it induces a self-help environment governed by the ‘balance of power’ logic in which states pursue relative gains (Berenskoetter, 2007; Waltz, 1979). For Realists, “politics are not…a function of ethics, but ethics of politics…morality is the product of power.” and the structure of world politics is, “defined not by all of the actors that flourish within them but by the major ones”, where the major actors are those with the greatest power (Carr, 2001, p. 82; Waltz, 1979, p. 93) Norms, therefore, are on the one hand, merely, “a reflection of the distribution of power in the world”, and on the other, temporary for, “all those international arrangements dignified by the label regime are only too easily upset when either the balance of bargaining power or the perception of national interest (or both together) change among those states who negotiate them.” (Mearsheimer, 1994, p. 7; Strange, 1982, p. 487) Realism, however, cannot explain the trends of compliance to the abolitionist trend, for if prevailing norms are the norms of the Great Powers, i.e. the U.S.A and China, then one would expect all states to be retentionist.

Indeed, in the materialist definition of the ‘national interest’ to which Realists subscribe, there is little to suggest why abolition would feature in any calculation of national interests at all because its acceptance or abolition is generally irrelevant to material gains. More fundamentally, the (untenable) paradigmatic assumption of a priori interests, ignores that people, “act in terms of their interpretations of, and intentions towards, their external conditions, rather than being governed directly by them” (Fay, 1975, p. 85). Although, to paraphrase Bourdieu (in Hopf, 2002), interested action is universal, ‘national interests’ only emerge from the identity of the state and this identity is affected by international norms.

Norm compliance is intimately connected with the state identity. Much of the discourse urging abolition in Europe has been couched in terms of a particular understanding of ‘civilized’ European identity. Not, only has the CoE emphasised their belief in “everyone’s right to life…a basic value in a democratic society”, but also that the death penalty “has no place in a civilized democracy” and that abolition is the mark of a civilized society and a civilized Europe.”[27] (Council of Europe, 1999 emphasis added; 2002)

A radical reconstruction of state identity has preceded abolition in South Africa in 1997. Under Apartheid, “the severe penal code and extensive use of the death penalty…were seen as necessary instruments to protect the white minority and to preserve white dominance” (Bae, 2007, p. 58). Hence, the emergence of the multicultural post-Apartheid state represented a ‘new’ South Africa that sought to construct an identity in opposition to the ‘Other’ of its repressive history and its ‘uncivilized’ forms of punishment. A moratorium on the death penalty in 1992, and complete abolition in 1997 were symbolic of this break from the past.

A concern for the identity, however, does not imply that material interests should be overlooked. The motivation for abolition in Ukraine was very much associated with the prospect of the material gains that could be attained by membership in the European Union. As the CoE is the ‘gateway’ to the EU, compliance with its rules of membership, i.e. abolition, was in the ‘national interest’ (Bae, 2007). However, the interest in ‘looking-West’ in the first place was only the result of a reconstruction of Ukrainian identity in the context post-Cold War Europe.

*

Cultural constructions of the U.S. identity have resisted all notions that the United States might be anything other than “the transplantation of a European civilization on the North American continent(Hemmer & Katzenstein, 2002, p. 600) Hence, non-compliance to the abolitionist norm does not appear to be explainable in terms of identity.

Thirty-eight states of the U.S.A. and the federal government retain the death penalty on their statutes. Hood (2004) points out that the United States, “continues to reject human rights arguments on the death penalty as defined by international consensus or treaty unless they are endorsed by its own Supreme Court”. This could be associated with an identity discourse of ‘American Exceptionalism’, but, perhaps more important for explaining retention is the nature of the institutions American political system. Bae (2007) describes the major features of US federalism and its electoral politics as populist, meaning that government decision makers are less resistant to public opinion than in other democracies. Unlike in most European democracies, most public officials including judges and district attorneys, are subject to the public vote. Hence, officials have less capacity to conform to international norms that do not resonate with public opinion. Popular opposition to the death penalty in the USA, like in many countries, has continued to be high, given the symbolic association between capital punishment and being ‘tough on crime’. Political elites, therefore, are not only constrained in their capacity to comply to the abolitionist (given the political consequences of abolishment), but also are structurally compelled to ‘outbid’ political rivals on law and order issues using the symbolic politics of capital punishment (ibid.)

Admittedly, this explanation for the retention of the death penalty in the USA neither accounts internal variation in compliance between states in the federal system, nor adequately accounts for non-compliance to the abolitionist norm itself. There are numerous factors that could account for compliance or non-compliance. Instead, the U.S. case is simply illustrative of the insufficiency of a ‘simple’ explanation of norm compliance in terms of the socialisation of political elites into new norms of acceptable behaviour. A concern for not only the motivation to comply with norms, which socialisation produces, but also the capacity and opportunity for elites to translate domestically unpopular international norms into practice. Indeed, Bae (2007) argues that a that the opportunity to disregard public opinion, such as a radical transformation of the domestic political system is crucial in explaining whether states comply strongly or weakly with the abolition norm, i.e. whether states become de jure, or de facto abolitionists.

In conclusion, it appears that in explaining norm compliance attention has to be paid both to the ‘international’ and the ‘domestic’. IR scholarship tends to look for international explanations for international phenomena, thus overlooking a critical arena of causality. The state elites who are subject to the socialisation processes which bring about policy convergence and norm compliance are always simultaneously domestically situated actors. The effects of international norms on domestic settings crucially depend on the nature of those domestic settings. Constructivism is not immune to this critique. To paraphrase Hopf (2002), it is time to recognise that constructivism begins at home.

Appendix

Figure 1: Trends in abolishment of the death penalty 1860-2009

Source: (Amnesty International, 2010)

Figure 2: Abolitionist states grouped by region

Source: (Amnesty International, 2010)

Figure 3: Executions in 2008 by region

Source: (Amnesty International, 2010)

Figure 4: Executions in 2008 by state

Source: (Amnesty International, 2010)

Table 1: Rates of ratification for International Treaties on the Death Penalty

| Treaty | Number of Member States | Number of Ratifying States | Rate of Ratification |

| UN | |||

| ICCPR* |

192 |

72 |

0.38 |

| Council of Europe | |||

| Protocol 6 ECHR** |

47 |

46 |

0.98 |

| Protocol 13 ECHR** |

47 |

42 |

0.89 |

| Organisation of American States | |||

| ACHR*** |

35 |

11 |

0.31 |

Note: * Second Optional Protocol to the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

** European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

*** The Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty

Source: (Council of Europe, 1983, 2002; Organization of American States, 1990; United Nations, 2010)

Bibliography

Amnesty International. (2010). Figures on the Death Penalty. Retrieved 18th February, 2010, from http://www.amnesty.org/en/death-penalty/numbers

Anckar, C. (2004). Determinants of the death penalty : a comparative study of the world. London: Routledge.

Badinter, R. (2004). Preface – Moving Towards Universal Abolition of the Death Penalty. In R. G. Hood (Ed.), The death penalty : beyond abolition (pp. 244 p.). Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Bae, S. (2007). When the state no longer kills : international human rights norms and abolition of capital punishment. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Bell, D. S. A. (2002). Anarchy, power and death: contemporary political realism as ideology. Journal of Political Ideologies, 7(2), 221 – 239.

Berenskoetter, F. (2007). Friends, there are no friends? An intimate reframing of the international. Millenium: Journal of International Studies, 35(3), 647.

Buzan, B. (1996). The timeless wisdom of realism? International Theory: Positivism & Beyond (pp. 47-65). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carr, E. H. (2001). The twenty years’ crisis, 1919-1939 : an introduction to the study of international relations. New York: Palgrave.

Council of Europe. (1983). Protocol No. 6 to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms concerning the abolition of the death penalty. Retrieved from http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/114.htm.

Council of Europe. (1999). Resolution 1179: Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Ukraine. Retrieved from http://assembly.coe.int/Documents/AdoptedText/TA99/eres1179.htm.

Council of Europe. (2002). Protocol No. 13 to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, concerning the abolition of the death penalty in all circumstances. Retrieved from http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/187.htm.

Fawn, R. (2001). Death Penalty as Democratization: Is the Council of Europe Hanging Itself? [Article]. Democratization, 8(2), 69.

Fay, B. (1975). Social theory and political practice. London: Allen and Unwin.

Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). International Norm Dynamics and Political Change. International Organization, 52(04), 887-917.

Hemmer, C. J., & Katzenstein, P. (2002). Why is There No NATO in Asia? Collective Identity, Regionalism, and the Origins of Multilateralism. International Organization, 56(03), 575-607.

Hood, R. G. (2004). Introduction – the Importance of Abolishing the Death Penalty. In R. G. Hood (Ed.), The death penalty : beyond abolition. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Hopf, T. (2002). Social construction of international politics: identities & foreign policies, Moscow, 1955 and 1999: Cornell Univ Pr.

Jepperson, R. L., Wendt, A., & Katzenstein, P. J. (1996). Norms, Identity, and Culture in National Security. In P. J. Katzenstein (Ed.), The culture of national security : norms and identity in world politics (pp. 33-75). New York: Columbia University Press.

Katzenstein, S. (2006). Why Some Norms Stall: The Persistence of the Death Penalty in the Era of Human Rights. Paper presented at Columbia University, Mini-APSA Conference April 28, 2006. Retrieved from http://www.columbiauniversity.net/cu/polisci/pdf-files/apsa_katzenstein.pdf

Keck, M., & Sikkink, K. (1999). Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics. International Social Science Journal, 51(159), 89-101.

Krasner, S. D. (1983). International regimes. Ithaca, N.Y. ; London: Cornell University Press.

Legro, J. W. (1997). Which Norms Matter? Revisiting the “Failure” of Internationalism. International Organization, 51(1), 31-63.

Manners, I. (2002). Normative power Europe: a contradiction in terms? Journal of Common Market Studies, 40, 235-258.

McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D., & Zald, M. N. (1996). Comparative perspectives on social movements : political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mearsheimer, J. (1994). The false promise of international institutions. International Security, 19(3), 5-49.

Moscovici, S. (1988). Notes towards a description of social representations. European journal of social psychology, 18(3), 211-250.

Neumayer, E. (2008). Death Penalty: The political foundations of the global trend towards abolition. Human Rights Review, 9(2), 241-268.

Organization of American States. (1990). A-53: Protocol To The American Convention On Human Rights To Abolish The Death Penalty. Retrieved from http://www.oas.org/Juridico/english/sigs/a-53.html.

Price, R. (1998). Compliance with international norms and the mines taboo. In Cameron, Lawson & Tolin (Eds.), To Walk Without Fear: The Global Movement to Ban Landmines (pp. 340-363). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rabben, L. (2002). Fierce legion of friends : a history of human rights campaigns and campaigners. Hyattsville, MD: Quixote Center.

Ravaud, C., & Trechsel, S. (1999). The Death Penalty and the Case-law of the Institutions of the European Convention of Human Rights. In C. o. Europe (Ed.), The Death Penalty : Abolition in Europe (pp. 79-90). Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Reiman, J. (1995). Justice, Civilization, and the Death Penalty: Answering van den Haag. In R. M. Baird & S. E. Rosenbaum (Eds.), Punishment and the death penalty : the current debate (pp. 175-205). Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books.

Rodio, E. B., & Schmitz, H. P. (forthcoming). Beyond norms and interests: understanding the evolution of transnational human rights activism. The International Journal of Human Rights. Retrieved from http://faculty.maxwell.syr.edu/hpschmitz/Papers/BeyondNormsInterests.pdf

Rosenberg, J. (1994). The empire of civil society : a critique of the realist theory of international relations. London: Verso.

Schabas, W. (1993). The abolition of the death penalty in international law: Grotius Pubns.

Schabas, W. (2002). The abolition of the death penalty in international law (3rd ed. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Strange, S. (1982). Cave! Hic Dragones: A Critique of Regime Analysis. International Organization, 36(2), 479-496.

Toscano, R. (1999). The United Nations and the Abolition of the Death Penalty. In C. o. Europe (Ed.), The Death Penalty : Abolition in Europe (pp. 91-104). Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Truskett, J. (2003). Death Penalty, International Law, and Human Rights, The. Tulsa. J. Comp. & Int’l L., 11, 557.

U.N. Secretariat. (2006). The Core International Human Rights Treaties. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/CoreTreatiesen.pdf.

United Nations. (2010). Treaty Series. Retrieved from http://treaties.un.org/Pages/src-TREATY-id-IV~12-chapter-4-lang-en-PageView.aspx.

Walker, R. J. B. (1993). Inside/Outside: International Relations as Political Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Waltz, K. N. (1979). Theory of international politics. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

Wyman, J. (1996). Vengeance Is Whose: The Death Penalty and Cultural Relativism in International Law. J. Transnat’l L. & Pol’y, 6, 543.

Zalewski, M. (1996). ‘All these theories yet the bodies keep piling up’. In S. M. Smith, K. Booth & M. Zalewski (Eds.), International theory : positivism and beyond (pp. 340-353). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[1] Where ‘abolition’ or ‘abolitionists’ is used I refer to the abolition of the death penalty for all crimes in law, and states that have abolished the death penalty for all crimes in law respectively, unless otherwise indicated.

[2] Furthermore, without careful argument some constructivist account could potentially make the logical error of post hoc ergo propter hoc. That is to say the apparent reasoning that in recent cases of abolition (or any policy change potentially coded as policy convergence), that as an anti-capital punishment norm emerged before abolition norms must be the cause of policy change.

[3] The power of the ‘inside/outside’ view of the human condition, i.e. the separation between ‘the domestic’ and ‘the international’, “practically defines the discipline of IR” (Buzan, 1996, p. 53; Walker, 1993). The claim that each sphere exhibits a unique logic and causal forces, insulated and independent from the other is fictitious. Although, IR theorists typically study ‘the international’ as a discrete object of study, this is, in fact, an unjustifiable separation (Bell, 2002; Rosenberg, 1994).

[4] Indeed, “abolition of the death penalty is generally considered to be an important element in democratic development for States breaking with a past characterized by terror, injustice and repression”. (Schabas, 2002, p. 9)

[5] Amnesty regards the pro-death penalty bias in popular opinion largely to be the result of an erroneous belief that it is an effective crime fighting measure. Evidence in Bae (2007) seems to confirm this belief. Although not relevant to this essay, the scholarly consensus is that the existence of the death penalty acts as no greater deterrent to prospective criminals than life imprisonment.

[6] Anckar (2004) thinks this is particularly telling given that only 9 percent of the Swedish population is in favour of the beating of children as a method of discipline in the home.

[7] The first instance of its use following reinstatement was in February 1998 (Fawn, 2001).

[8] Fawn (2001) also regards the ‘example’ of the democracy of USA to have been an example as well.

[9] That is to say abolition removes an important symbol of state power, indicates a reduction in absolute authority and involves going against public opinion unnecessarily. This would suggest that a state has few (domestic) interests in abolition.

[10] Norms have been defined in different ways. Mearsheimer (1994, p. 8) states that “norms…are core beliefs about standards of appropriate state behaviour”; Krasner (1983, p. 2) defines norms as “standards of behaviour defined in terms of rights and obligations”; and Jepperson, Wendt & Katzenstein (1996, p. 54) define norms as, “collective expectations about proper behaviour for a given identity.” Each definition portrays certain elements of the authors’ theoretical perspective, but in each definition the core element affirms that norms are concerned with behaviour that is ‘good’, ‘right’, ‘expected’. In this sense, abolition of the death penalty is, increasingly, expected of states.

[11] Amnesty International, for instance, expanded its mandate to include opposition to the death penalty in 1973, with an active campaign beginning in 1977 (Amnesty International, 2010; Rabben, 2002).

[12] Article 2.1, however, allows, “for the application of the death penalty in time of war pursuant to a conviction for a most serious crime of a military nature committed during wartime” (U.N. Secretariat, 2006, p. 53)

[13] The difference between Protocol 6 and Protocol 13 is that Protocol 6, in Article 2, makes legal provisions for deviation from Article 1 in times of war, whereas Protocol 13 provides no such provision and constitutes a complete ban in all circumstances (Council of Europe, 1983, 2002)

[14] Article 2, however, allows for the use of the death penalty in wartime if State Parties affirm their right to do so upon ratification. (Organization of American States, 1990).

[15] Krasner (1983, p. 2): “Principles are beliefs of fact, causation, and rectitude. Norms are standards of behaviour defined in terms of rights and obligations. Rules are specific prescriptions or proscriptions for action. Decision-making procedures are prevailing practices for making and implementing collective choice.”

[16] The perception of norm violation is indicative that a norm is in existence. For example, although murders sometimes occur, it does not mean that there is no anti-murder norm (Price, 1998). The success of a norm can be gauged by how much the n0rm violator justifies their action using human rights language, thereby accepting the framing of the issue as a human rights issue (Katzenstein, 2006).

[17] For example, when the UN second optional protocol was put to vote in 1989, Egypt declared it “a racist, imperialist idea which certain countries were seeking to impose [on the] countries which still had the death penalty.”(Wyman, 1996, p. 549) Then, in 1994, upon the submission of a draft resolution to the UN calling for a moratorium by the year 2000, the Singapore delegate stated that “it strongly opposed efforts by certain states to use the United Nations to impose their own values and systems of justice on other countries” and that the abolition of death penalty did not necessarily further “human dignity.” (Schabas, 1993, p. 12)

[18] Transnational advocacy networks are, “networks of activists, distinguishable largely by the centrality of principled ideas or values in motivating their formation”, in as much to say as, “those actors working internationally on an issue, who are bound together by shared values, a common discourse, and dense exchanges of information and services.” (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 89)

[19] Framing, refers to the “conscious strategic efforts by groups of people to fashion shared understandings of the world and of themselves that legitimate and motivate collective action”(McAdam, McCarthy, & Zald, 1996, p. 6).

[20] Indeed, the CoE has been, “considered to be the oldest, most effective, and most robust international human rights organization in operation today.” (Bae, 2007, p. 24)

[21] Despite ‘mission creep’ within the organisation, Amnesty’s abolition campaign remains significant. For instance, between 1994 and 2004 20 percent of Amnesty’s background reports and 11 percent of their press releases on China (the biggest ‘killer’ – see Figure 4) concerned the death penalty and executions (Rodio & Schmitz, forthcoming).

[22] It is perhaps this understanding which lies behind Bae’s (2oo8) suggestion that abolitionists can be divided into two groups. The first generation of abolitionists spanning from the end of the Second World War, and peaking in the 1970s, she suggests, were mostly European countries that abolished for humanitarian or religious reasons. Whereas, the second generation of abolitionists, mostly from Eastern Europe and African, decided to abolish in order to comply with international norms.

[23]Information politics: “the ability to move politically usable information quickly and credibly to where it will have the most impact” (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 95).

[24] Symbolic politics: “ the ability to call upon symbols, actions or stories that make sense of a situation or claim for an audience that is frequently far away” (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 95).

[25] Leverage politics: “the ability to call upon powerful actors to affect a situation where weaker members of a network are unlikely to have influence” (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 95).

[26] Accountability politics: “the effort to oblige more powerful actors to act on vaguer policies” (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 95).

[27] Indeed, Reiman (1995) links claims that “the abolition of the death penalty is part of the civilizing mission of modern states” (p. 175). Persistent pro-capital punishment public opinion seems to indicate that the discourse of a ‘civilized’ European identity seems to be restricted to elites.

—

Written by: Tom Thornley

Written at: SOAS, University of London

Written for: Dr Fiona Adamson

Date written: March, 2010

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Resonance of Name-Shaming in Global Politics: The Case of Human Rights Watch

- Human Rights and Security in Public Emergencies

- Cultural Relativism in R.J. Vincent’s “Human Rights and International Relations”

- The Dangerous Double Game: The Coexistence of Nuclear Weapons and Human Rights

- Human Rights Law as a Control on the Exercise of Power in the UK

- Navigating the Complexities of Business and Human Rights