The continued survival of the Kim regime at the head of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea has for a long time now been somewhat of a mystery to international scholars. Since the early 1990’s and even before there has been a large body of literature predicting the demise of the regime and the state it controls, however despite some reform the DPRK remains largely unchanged.

The Juche ideology employed by the regime is at the heart of North Korea’s longevity and its success in providing continued internal legitimacy for the regime. This ideology of ‘self-reliance’ has moulded a state which aims to exist in economic, political and military isolation from the rest of the world. While this proved to be initially very successful, since the 1990’s when North Korea experienced the double shock of the USSR’s disintegration and domestic famine, it has become increasingly reliant on food aid to fend off starvation.

Recent moves by the regime to establish an unprecedented third generation of the Kim dynasty have brought the DPRK to the world’s attention and discussion of the possible future path for North Korea remains rife. If the DPRK is to avoid further and increased reliance on food aid the Juche ideology, despite its success in insulating the regime from internal and external threats, must be removed from its central position in North Korean political and economic life.

I. Introduction

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) has, over its almost 62 year history, been a source of mystery, intrigue and more recently frustration to the outside world. The northern half of the Korean peninsula, established as an independent state in the aftermath of World War II under the occupation of Soviet forces has become a ‘hermit kingdom’, pariah state and in the language of the post-9/11 world, a prominent member of the ‘axis of evil’. Long thought of as a mere satellite of more powerful Communist neighbours the USSR and China, the end of the Cold War, and even before this, was thought by many prominent scholars to herald its demise as a state in its current form. However in 2010 the North Korean state under the regime of Kim Jong Il, having replaced his father Kim Il Sung as all powerful leader, continues to exist and while it certainly cannot be said to be thriving, shows little outward sign of imminent collapse.

In this dissertation I will examine the role North Korean state ideology, Juche or self-reliance, has played in the development and structure of the DPRK contending that this ideology has played a major role in creating the conditions under which the state currently exists and providing the Kim regime with the legitimacy they need to rule. I hope to draw some conclusions regarding whether Juche, as a policy guide for the North Korean ruling elite can be judged a success, in particular with regard to regime survival, economic performance and political freedom. The role and influence of Juche has been widely debated by international scholars, and has developed over time as the fortunes of the DPRK have fluctuated in response to its own policies and the effects of crucial external factors. These will be investigated in more detail later. “North Korea has been variously described as ‘corporatist’, ‘fascist’, ‘theocratic’, ‘feudal’ and ‘Stalinist’ and Juche itself as ‘political ideology’, ‘myth’, ‘theology’ or ‘propaganda’.”[1] However, the focus of this work is not primarily to define Juche but to examine its effects on North Korean policy decisions and the political environment.

My own analysis of Juche consists of an investigation into official statements and speeches made by the DPRK’s leaders; Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il as well as an analysis of changes in the state constitution and data concerning economic output. It is important to note at this stage that primary sources relating to North Korea especially where an analysis of ‘success’ is concerned are often incomplete, revised by the regime and largely compromised by propaganda efforts. As a result of these factors reliance on these sources alone is impossible and I will draw on a wide range of views and analyses expressed by international scholars to deepen and broaden the reach of my study.

I have organised this study into 5 sections. I will start with a background chapter to contextualize my approach with specific emphasis on why I have chosen to investigate this topic as well as analysis of key themes. In this case these are a definition of Juche and its relationship to ideology and an investigation into what constitutes success in a North Korean context. Chapter 2 will investigate the factors which were important in bringing Juche into existence as a formally expressed state ideology. These include the forces of Communism, Nationalism and the historical experience of Korea and Juche’s founder Kim Il Sung as respectively, a colony of Japan and a nationalist resistance fighter. I will also concentrate on the early years of the DPRK during which what has been described as a ‘Korean Revolution’ was carried out and Kim Il Sung rose from relative obscurity to a position of almost unrivalled personal power and influence. The third chapter will look at Juche itself in detail and the effects it has had on North Korea’s politics, economy and society. Most notably this will include an analysis of the use and implementation of three Juche inspired policies; the Chollima movement, the Taean method of industrial production and the Chongsangri method of agricultural production. Chapter 4 will investigate the role of Kim Jong Il in the evolution of Juche, and the reforms he enacted in an attempt to ease the pressures created by the inherent long-term weaknesses of the centralizing system implemented by his father. By the time of his succession these were becoming increasingly problematic for the DPRK. Finally I will conclude my study by bringing together the elements mentioned above and attempt to make some statements about the degree to which we can term Juche a successful part of the DPRK’s survival as a state.

II. Interpreting the North Korean Regime

Recent events have thrust North Korea into the limelight once again. Continuing border tension with the Republic of Korea exemplified by the sinking of the South Korean Warship Cheonan as well as Kim Jong Il’s plans to develop nuclear weapons and pass on leadership of the regime to a third generation, Kim Jong Un, have caused an intermittent and short lived notoriety that masks a more general widespread ignorance of the ‘hermit kingdom’. The fact that “barely 1,500 people a year visit North Korea…several thousand fewer than make it to the British Lawnmower Museum”[2] shows the degree to which the DPRK has removed itself from the rest of the globally interconnected World. Despite this insistence on remaining almost totally closed off to outsiders the continuing importance of North Korean Politics to the World Stage is clear.

Of special importance is the issue of Nuclear Weapons Development by the regime. The DPRK’s insistence on the continuation of attempts to develop long range missiles and eventually achieve the required level of miniaturization to create a nuclear armed warhead for these weapons has continued to create concern in the international community. This is a factor in the more aggressive stance taken by Lee Myung-Bak’s South Korean government, whose pre-election pledge to end the ‘Sunshine Policy’ that created stable inter-Korean relations in the post Kim Il Sung period has been popular in South Korea, but has led to numerous skirmishes and simmering border tensions along the DMZ.[3] Tensions on the Korean peninsula are of particular concern not just to Koreans but to the inhabitants of the larger North East Asian area, especially Japan and China. The Japanese would be a potential target of any future North Korean missile launch and in fact has in the past been the victim of North Korean incursions to abduct members of its population. Chinese officials have more to fear from the possibility of ‘regime implosion’ in the DPRK, questions over Kim Jong Il’s deteriorating health have led to rampant speculation over future dynastic succession in North Korea, speculation that has only grown with the simultaneous promotion of Kim Jong Un and Kim Jong Il’s sister, Kim Kyong-Hui.[4] The consequences of a power vacuum or struggle creating instability in the regime would be a tide of refugees flooding across the border to China. This combined with the eventual possibility of an enlarged, democratically unified single Korean state would undoubtedly cause China to re-evaluate its strategic priorities. An increased knowledge and understanding of North Korea and the motivation behind its actions will hopefully lead to action being taken to avoid where possible the most dangerous aspects of North Korea’s future development path wherever it may lead. I hope that this study of Juche’s relationship to regime collapse or stabilization can play a small part in this process.

Literature Review

Existing studies concerning North Korea have changed in focus and conclusion as the state has developed over the years since the Korean War (1950-53) and as more sources have become available; these include the testimony of North Korean defectors, de-classified US and Soviet documents and the prolific output of the North Korean Government’s publishing house. Works of the 1960’s drew attention to the relatively high living standards of North Koreans at that time of economic dynamism and compared the DPRK favourably with its Southern Neighbour. Joan Robinson’s article “Korean Miracle” gives possibly the most positive review of Kim Il Sung’s regime when she talks of his economic achievements putting those of his contemporary rivals “in the shade.”[5] Later attempts at analysis used the increasing availability of economic data which although widely believed to be unreliable gave scholars insight into how the regime operated. Most works concentrate on trying to define the regime and its ideology and portray the state as some offshoot of Soviet Marxism that had Communism thrust upon it by the USSR at birth. The most significant study of this kind, Scalapino & Lee’s “Communism in Korea” states that: “North Korea came to Communism not via an indigenous revolution, not through a union of Communism and nationalism, but on the backs of the Red Army.”[6] More recent studies of the formation of the DPRK have described Korean Communism as much more complex and have given much greater weight to the effect of indigenous nationalism and elements of Korean history and culture as crucial aspects of the DPRK’s development. Charles K. Armstrong argues that the formation of the DPRK was “more than a revolution from abroad, imposed by fiat of the Soviet occupation, but was shaped by local circumstances and recent historical legacies.”[7] Juche is a significant though often minor part of these works; my analysis will give Juche the central role that I feel it deserves.

In the years following the death of Kim Il Sung (1994) commentators have increasingly referred to North Korea in the language of failure, expecting that without his leadership the regime would quickly collapse, this was as is clear now incorrect. Whan Kihl Young in his work ‘North Korea: The Politics of Regime Survival’ exhibits a rather close-minded attitude when he concludes that only “since the death of its founding leader…has [Korea] been a failing state trapped in a cycle of economic poverty and political repression.”[8] This analysis fails to acknowledge the roots of North Korea’s ‘failure’ which developed over the long term from policies enacted by Kim Il Sung. The refusal of the ‘second republic’ under Kim Jong Il to buckle has led many to speculate on how survival has been achieved. Economic reforms have been analysed, and there has been much speculation as to whether the DPRK can continue to endure, will implode catastrophically, or reform and reintegrate into International society following the Chinese model. The changes brought about by Kim Il Jong and the fact of his hereditary rise to power has led some scholars to conclude that “Juche can mean whatever the regime wants it to mean.”[9] My own study seeks to investigate the role that Juche has played throughout the life of the DPRK; beginning with how and why it came to be adopted by the regime, how it has worked in practise to effect North Korean policies, and finally to answer the question of whether it can be termed a true ideology and if its relationship with the continued survival of North Korea in its current form can be called a success.

Key Concepts: Juche & Success

In order to approach a study of Juche in North Korea it is important firstly to define the parameters of this study. This section will seek to define Juche and crucially the concept of success in the DPRK context. Juche was introduced to the DPRK by Kim Il Sung in a speech of 28th December 1955 as “the sole guiding idea of the Government of the Republic. Juche, independence, self-reliance and self-defence are the guiding principles of our revolution.”[10] Although these goals remained the core of the ideological concept Juche’s unique attributes include flexibility, enabled by the lack of a rigid and thorough definition, and pragmatism. The regime has manipulated state philosophy to best reflect each set of challenging circumstances it has faced. There are many uncertainties surrounding the North Korean state however, one thing we can be clear on, Juche in its pure form described above has not been achieved. The DPRK has moved from reliance on the USSR and the Soviet Bloc, to Chinese support (most notably and crucially in the Korean War) and now to aid from the wider International Community and its neighbour to the South. So in this way it can be seen that Juche has not achieved great success. However, could any state or system genuinely achieve self-reliance? It seems unlikely. Although economically Juche seems to be elaborate propaganda (although this has not been without benefit) politically North Korea has managed to maintain a significant and impressive independence of action, Juche has played an important part in this. We need to judge ‘success’ within the North Korean context, that of a small and at the time of its inception, newly free nation that was almost completely destroyed during the Korean War, has been surrounded by much more powerful neighbours throughout its existence and has survived under the continuous threat of War. Marcus Noland, using analysis of economic decline in conjunction with political stability describes the DPRK within this context as achieving a “combination of longevity and underperformance [which] is unparalleled.”[11] I believe that the Juche ideology has had a significant impact on both this underperformance and longevity, or what we might call survival, of the North Korean state – Juche has provided the Kim regime with legitimacy in a truly Weberian sense.

Clearly, when viewed alongside its contemporary neighbours, the Pyongyang regime’s economic situation seems untenable. Certainly when compared to the Republic to the south failure is magnified, but Seoul remains home to a large population of US soldiers, something that remains a burden on Korean pride even today. Furthermore, its current economic and military superiority is a relatively recent role reversal and did not always seem assured; the effects of the 1997 IMF financial crisis have been described as a ‘national humiliation’ in the south, although they are insignificant when compared to problems in the north.[12] A more appropriate comparison can be observed when the DPRK is placed alongside those it sought to emulate at birth. The state’s very success in surviving while other Communist regimes were swept away with the USSR or have reformed to an almost unrecognisable degree in the case of China is a more appropriate comparison. The DPRK’s continued existence and its continued ability to exhibit political freedom of choice, however erratic those choices may seem from the outside, is if not miraculous, certainly worthy of further investigation and enhanced understanding. I hope to show the role that Juche has played in this limited measure of self-reliance. Charles K. Armstrong uniquely illustrates the specific aims for which Juche was employed and comes to this conclusion regarding the success of Kim Il Sung and his peers.

“If their goal was the creation of a communist Korean state that would establish deep and lasting roots, that would be distinctly and idiosyncratically ‘Korean’ and thus be able to survive a horrendously destructive war, decades of confrontation with South Korea and the United States, a prolonged economic crisis, famine, and the collapse of nearly all other communist states – including the USSR itself – then the guerrillas, cadres, peasants, and intellectuals who brought the DPRK into being in the shadow of the Soviet occupation surely succeeded.”[13]

It is with this in mind, the uniqueness of the Korean situation and experience, that I begin my analysis of Juche’s relationship to the DPRK regime’s success.

III. The basis and development of Juche

Roots of Ideology

Although not enunciated by Kim Il Sung until 1955, Juche’s beginnings can be traced to far before the existence of its home state, and is based on both the personal beliefs of Kim and long held opinions of the Korean population at large, “that a small and strategically located state such as North Korea will become dominated by its powerful neighbours if it becomes unduly reliant on them.”[14] This belief provoked the fear of the nation “being ‘de-Koreanized’ and losing control over its own national identity.”[15] Juche’s development can be related to a wide range of factors and in fact exists in a hybridized form of many seemingly opposed but related factors. The three main pillars on which Juche was built were Kim Il Sung’s personal experience, Korea’s contemporary situation and deeply-rooted Korean cultural traditions.

Although Kim Il Sung’s exploits before the formation of the DPRK have been wildly exaggerated and overtaken by the cult surrounding his status as ‘Suryong’ (Supreme Leader) and father of the nation, an investigation into his time as a guerrilla fighter in Manchuria and briefly the USSR shows that his experiences at this time were important in bringing Juche into existence. As a leader of a small and isolated group of fiercely nationalist guerrilla fighters, who were prepared to go to any lengths to bring freedom to the Korean Peninsula, Kim’s personal circumstances echo those of the state he ruled for over 40 years. In fact, the DPRK has been described as a ‘guerrilla band state’, recognizing the importance of these years in the DPRK creation myth as promoted by the regime, Kim Il Sung directly referenced this period repeatedly – “our republic has grown from the deep historical roots of the glorious anti-Japanese revolutionary struggle.”[16] The following, from Scott Snyder’s analysis of DPRK behaviour could apply equally to the Juche state or its founder’s pre-independence tactics, “conventional tactics and direct confrontations with the enemy – were likely to have counterproductive outcomes. However, the threat even from a small and unpredictable force would cause the enemy to hesitate.”[17] This approach was later applied not only to the DPRK’s enemies, but also to its relations with the USSR and China, helping to navigate a path between the two competing neighbours and achieving undue influence in their superpower dispute. Furthermore, it is noticeable that those comrades who shared Kim’s experiences in Manchuria were those who remained in high positions amongst the leadership of the DPRK, well after any resistance to Kim’s rule had been purged. The shared experiences and world view of this fiercely nationalist band of warriors were transformed into norms of state behaviour when the threats of subjugation to foreign rule and culture failed to disappear after independence. It was this nationalism, combined with their vision of Socialism as it related to landless and colonized peasants, that was instilled during the years of campaigning amongst Chinese and Russian Communists that influenced the development of Juche.

Perhaps the most significant factor in the formation of Juche was the situation that Korea found itself in as it emerged from Japanese colonial rule. Scholars in the past described the DPRK as Stalinist, and while the influence of Marxist-Leninist thought has often been over-emphasised in discussions of Juche, its role as an inspiration to Kim and his comrades was crucial. However, Kim Il Sung placed emphasis on the uniqueness of the DPRK’s Marxism: “we should firmly adhere to Marxist-Leninist principles, applying them in a creative way to suit the specific conditions and national characteristics of our country.”[18] Communist ideology has always been subjugated to Korean culture and specifically the North’s geo-political situation. This combination of Marxist thought, in its Korean form, with Nationalist fervour has been described as “the most successful example of the indigenization of Stalinism in the communist world.”[19] There can be little doubt that the USSR’s influence was crucial, in fact before the liberation of Korea the guerrilla Kim Il Sung was given the rank of Captain in the Soviet Army. Juche policies instigated as soon as independence had been achieved replicated those found in the USSR, such as: land reform, the nationalization of industry, equal status for women and centralized planning. Although there are significant differences between the way Socialism operated in the USSR and in Korea, the USSR, especially its Stalinist period, remained a point of reference for the DPRK. This influence combined with a desire to preserve Korean culture after Japanese attempts to extinguish the Korean identity was a second element in Juche’s formation. In a demonstration of the continuing similarities between North and South despite their long division, this has also been cited as important in the South’s bid to promote Korea as a cultural entity, independent of its more famous neighbours Japan and China.[20] This factor was often overlooked during Cold War manoeuvring but the ‘humiliation’ of dominance by a foreign power was critical in forming Juche’s strive for self-reliance.[21] The colonial period was also important in providing the North with an early economic advantage over its southern rival, as the Japanese had concentrated their industrial development in what was to become the DPRK.[22] Although most collaborators were ruthlessly eliminated elements of the Japanese system, including parts of its legal code and well trained industrial experts were retained.

Cultural traditions dating back centuries are also an inescapable bedrock of influence underpinning everything the DPRK does. This fact is especially true of Juche ideology and its relationship to Confucianism. Many of the elements of this traditional Asian belief system are emphasised in Juche ideology; most obviously in the cult of personality surrounding not only Kim Il Sung, but also his family and ancestors, and the filial piety and devoted loyalty demonstrated by Kim Jong Il in the period following his father’s death. Korea is even now thought of as the most Confucian of societies, and Juche has been able to harness the well established norms of this philosophy, and put them to use as promoters of loyalty and reference to the regime and especially to the Suryong himself. “Although Juche clearly utilises elements of Confucian thought that are deeply ingrained in the Korean psyche, the government does not encourage the study of Confucius”,[23] so Confucianism informs Juche but has not been allowed to undermine or act as an alternative to its more recently invented philosophical rival. In the DPRK Juche is an all pervasive, all powerful and inescapable fact of daily life. As we shall see its strengths and weaknesses have pervaded all of the states policy choices, and despite its pragmatic and flexible nature Juche remains core to whatever success the DPRK achieves.

The North Korean Revolution

As soon as possible North Korean’s used the above described set of circumstances to take the first step to becoming a Juche state. As a result, the use of Juche as a policy guide can be observed in the very first decisions made by the newly independent population. The indigenous cultural roots of Juche, meant that bottom up peasant mobilisation was from the very early stages of independence fused with the top down influence of the liberating Soviet forces and the Communist Koreans who came with them, rapidly putting Korea on the path to ‘self-reliance’.

The grassroots of the revolution were the People’s Committees (PCs); these locally organised groups successfully filled the immediate power vacuum after the collapse and withdrawal of Japanese forces. It was these groups, despite what many outside of Korea at the time may have believed, that were of crucial importance in governing the day to day lives of Koreans from the very first days of independence. The co-operation and recognition of the desire to achieve quick success, between local Koreans and liberating Soviets, shows the harmony that existed in how they both wanted the North to develop.[24] “The Soviets encouraged the People’s Committees to become the governing units and usually passed any directive to the Korean people through them.”[25] The fact that Soviet planners had not laid down detailed post-invasion plans for Korea provided the PCs with crucial breathing space to establish what to many was an entirely unexpected level of the autonomy, that was later to become the State’s obsession. Although not planning to take control over the North directly Soviet motivation was to keep the North as a bulwark against the US sponsored regime to the south, and most significantly at the time, act as a countermeasure against a future re-militarized Japan. In this way, the Koreans were free to establish the political norms that they desired. Of course, the Soviet job was made much easier by the leftist nature of Korean society. In this way, “the Soviet occupation provided a womb in which this politics could be nurtured … thus it stimulated a rapid mobilization across North Korea.”[26] Although as we shall see the Soviets were concerned with who would be running the regime in the North after their withdrawal, they were not overly troubled by the real authority established from the grassroots, no doubt recognising the benefit of Korean’s choosing a Socialist revolution for themselves rather than having it imposed upon them. The self-reliance demonstrated by the PCs at this time provided a crucial template and inspiration for later state led, top down Juche policies and rhetoric.

Although recognizing the benefit and wisdom of stable PC’s throughout the North the Soviets were far from passive in their relationship with the revolutionary forces sweeping Korea at this time. Central government was understandably slower to emerge than local organisation; this was due to a lack of civilian officials within the Soviet vanguard and the logistical difficulties of those returning to Korea, not least Kim Il Sung’s Kapsan or Manchurian faction, who would make up the initial governing class. Centralized government emerged in February 1946 in the guise of the North Korean Provisional People’s Committee, a year later the provisional element was removed and in September 1948 the DPRK established. These changes marked increasing central involvement in the local PCs. It was only through Soviet guidance that the politics expressed on a local level could be nationally implemented. “Politics from the bottom up would thus translate into social reform from the top down.”[27] The social reforms implemented included land and labour reform, the nationalisation of industry and laws to give Women equality. The granting of equal rights to women is perhaps surprising given the Confucian nature of Korean society and demonstrates a measure of tension between traditional culture and modern Marxist thought. Its development was in line with what had already happened in the USSR but also, “was quite consistent with the policy of Kim Il Sung and the NKPPC in mobilizing the marginal elements of North Korean society.”[28] This tactic, used to give the emerging regime greater legitimacy, was perhaps an early demonstration of Kim’s ability to put pragmatism at the heart of his political beliefs. Hierarchical organisation in the Confucian style was to be given much more prominence in Juche thought later, especially during the DPRK’s ‘neo-traditional’ stage coinciding with the desire to help stabilize and legitimize the succession of Kim Jong Il.

Crucial to the revolution was the new state’s constitution, as its development was overseen by Soviet advisors; it’s not surprising that, “in broad outline and overall institutional structure, the 1948 constitution of the DPRK was very similar to the 1936 Soviet constitution.”[29] Although interestingly it did not refer to Marxism-Leninism as a ruling ideology, recognition perhaps that appeals to Korean nationalism would be of more benefit than an imported foreign system. The constitution was designed to reflect the stage of the DPRK’s development at the time, people’s democratic revolution. The democratic basis being the emphasis on bringing previously marginal elements of Korean society: peasants, women and youth, into the centre. These elements could then be harnessed to create Juche.

“Ours is a new type of democracy most suited to the reality of Korea … our democracy opposes dependence on and submission to other countries and requires adhering to an independent stand and creative attitude … this democracy demands the formation of a national united front represented by all anti-imperialist and patriotic classes … and the coalition of broad sections of patriotic people.”[30]

These measures proved to be very popular, strengthening legitimacy and providing much needed regime stability for the DPRK in its infant state.

Although Juche itself was not part of the revolution, the elements of indigenous Confucian social norms which helped to make the establishment of PCs a natural reaction to the circumstances (ultra-nationalism built on a desire to avoid foreign dominance and Soviet inspired Marxism which led to Juche’s formulation) were critical in the development of PCs and in bringing an initial element of autonomy and self-reliance to the DPRK. This movement’s startling speed and popularity demonstrates its success and made it clear that future emphasis on self-reliance, with necessary modifications, would be a reliable route to regime stability for the Kim dynasty.

Kim Il Sung’s Rise to power and the creation of a Juche state.

Kim Il Sung’s rise to prominence and the establishment and longevity of Juche are two deeply entwined and inter-connected processes, so much so that after a certain period in DPRK history, the 1970’s, Juche was often synonymous with Kim’s own cult of personality ‘Kim Il Sung-ism’. It is important to understand how Kim came to prominence among the North Korean political elite and was then able to remove any political threats to his position because Juche, or at least those elements that would come to create Juche, were of key importance in this process, effectively demonstrating the ideology’s most significant success; creating a stable political environment in which the Kim dynasty was able to thrive. That Kim Il Sung was in some way ‘chosen’ by the USSR to be the North Korean ruler, or at least to be set on the path to great influence is beyond dispute. However, this was just one element in his rise to complete control. Kim shrewdly capitalised on the circumstances of his experience as a guerrilla and exploited the feelings of the masses to stabilise his position initially. His use “of a widely inclusive ‘united front’ approach to build coalitions and gain popular support”[31] was highly successful in elevating his own faction to prominence. This combined with the absence of any well established rival among the various Communist sympathizing factions present in or returning to North Korea after liberation enabled Kim to develop from hand-picked Soviet revolutionary leader to undisputed dictator.[32] The same mix of factors that enabled the smooth transition from colony to independent state allowed Kim Il Sung to ascend to the eventual position of ‘Suryong’ (Great Leader) and develop the ideology that would harness these factors into the national ideology of Juche.

Although Kim Il Sung himself did not return to Korea until 19th September 1945, a month or so after the surrender of the Japanese, and was not able to establish unrivalled power until much later when the Korean Revolution was well underway his ability to harness the nationalism of Koreans at the time and project himself successfully as the liberator and protector of the North were key in enabling his ascent to a position of unrivalled power within the DPRK.

“Kim Il Sung successfully posed as the most patriotic, independent-minded national leader in Korea….Kim’s appeals to self-reliance seemed at the time to be a solution to further loss of sovereignty in the face of massive economic involvement and military occupation.”[33]

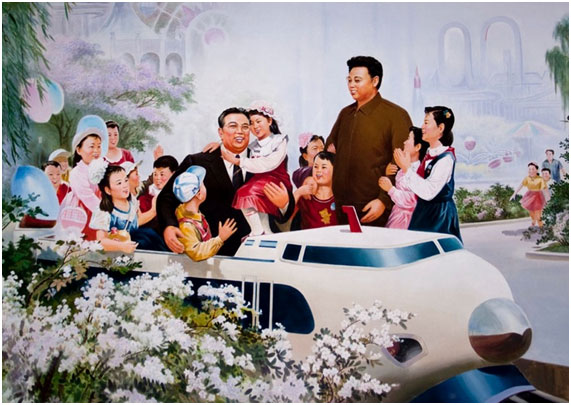

![]()

That Kim made the right appeals to a humiliated population is clear, how he came to be in the position to make these appeals less so. Kim made his first public appearance in October 1945 when he was introduced as ‘General Kim Il Sung’, backed by Soviet military officers. Bearing in mind that much of the information disseminated regarding Kim even at this time, was propaganda, including his title of General, what made him the chosen one? There are many factors which taken together meant that he was the best option for the Soviet forces who wished to complete their limited aims quickly and with as little fuss as possible.

Bruce Cumings has outlined four factors that together presented Kim Il Sung with the best opportunity among the potential North Korean leaders to actually achieve dominance.[34] The first of these was his ‘fame’ at the time – although certainly and deliberately inflated, Kim’s war-time record was widely known and respected by those whose opinions counted. The Pyongyang Times referred to Kim as “the incomparable patriot, national hero, the ever victorious, brilliant field commander with a will of iron.”[35] Although such rhetoric was wildly overblown, it was important in spreading his message and beginning his ‘myth’ among Koreans. While acknowledging Kim’s nationalism, any reference to Kim as a good Communist is conspicuous by its absence. Related to the first point is that Kim had not been captured by or in any way associated with the Japanese forces. This absence of opportunity for collusion in any form meant a lot to Koreans who were used to their leaders need to compromise their principles in order merely to survive under Japanese rule. Also of importance were those who were later to become first, the Kapsan faction and then, the upper echelons of the DPRK regime; Kim’s guerrilla comrades. Although small in number this band was fiercely loyal and dedicated to their leader, something that could not be said for the supporters of others. Finally, Kim was seen as a break from the past, representing a new start for the Korean nation. His opponents’ age and positions meant they were tainted in the eyes of Koreans by the failure to organise successful resistance to the Japanese, and by their inability to maintain any type of successfully unified Communist party, even an underground one, in the eyes of the Soviets. Kim was presented in stark contrast as the energetic, youthful man to bring proud and honourable independence to a ‘new’ Korea. Furthermore his personal beliefs and experience presented nationalist ideals combined with Communist policies that were attractive to both the Korean population and the Soviet command.

North Korean efforts to establish a cult of personality around Kim Il Sung started almost immediately, and while largely based on the systems that had grown up surrounding Stalin in the USSR and Mao in China, Kim’s cult had the by now familiar Korean cultural twist that was necessary in order to indigenize and legitimize an idea that was covertly foreign. Kim began to be referred to as ‘Suryong’ before the DPRK even existed and as we shall see this term and the way it was used by the regime was of crucial importance in maintaining their legitimacy, especially during the period of uncertainty after Kim Il Sung’s death and Kim Jong Il’s succession.[36] The cult combined local Confucian belief with imported Communist ideas, and demanded from the Korean people “not only adoration of him personally but also reverence for his parents and loyalty to his son.”[37] The establishment of the cult was made comparatively easy by the traditions surrounding Confucian thought, in particular that “flattery of rulers, coupled with the idolatory towards them, is a centuries old art for career advancement.”[38] Supporting Kim Il Sung in his efforts to stabilise control of North Korea must have come naturally to many in the political elite. As the cult developed the family history of Kim Il Sung was embellished and raised to a level of reverence where it was “presented as one and the same with the flow of North Korea’s modern history.”[39] The cult of Kim Il Sung-ism combined with Juche to form a structurally mythical belief system sustained by “a stable state of permanent crisis, an institutionalized, continuous emergency,”[40] which the masses had to invest in if they were to survive as independently Korean. The fact that they were able to do this and continue to do so is one of the successes of Juche and the Kim regime it legitimizes. The myths that have sustained the system throughout the regime’s existence were formed in this short but crucial period of North Korean experience between Japanese withdrawal and the DPRK’s formation, this period was the basis for all that followed, both success and failure.

IV. Juche in North Korean Politics, Economy and Society

Politics First and Regime Consolidation

Although Kim Il Sung has been widely portrayed as the figurehead of North Korea since almost immediately after independence, the years up to the early 1950’s were characterized more by coalition politics than the dictatorship that we recognize now. Kim Il Sung was able to harness the same mix of Juche style tactics that were examined above, to out-manoeuvre his political opponents and begin the process of creating and sustaining the Kim dynasty. Kim’s position as undisputed leader was not assured until the late 1950’s. His predominance was based on having “posed as the most patriotic, independent-minded national leader in Korea [and] successfully depicted his ideological opponents in the party as a national security risk.”[41] The North Korean Worker’s Party (NKWP), only formed in August of 1946 would be the vehicle which propelled Kim to power. From its beginnings at this time to a marginal minority party, the NKWP in less than 3 years rose to become a mass movement and the official Communist party of not just the North but the whole of the Korean peninsula, which dominated fledgling North Korea politics above its increasingly ineffectual coalition partners. Kim Il Sung, having used similar tactics to those that had served him well as a guerrilla fighter, and with ceaseless self-promotion as the leading nationalist force, was now the undisputed party leader. Kim Il Sung was declared Premier on the day that the DPRK officially came into existence on 9th September 1948. Although it is arguably true that “endorsement of Kim Il Sung by the Soviet occupation forces was the most important advantage he had in his competition with political rivals,”[42] it would be wrong to dismiss Kim’s own qualities and the appeal to Juche which gave him the largest popular base, and therefore the ‘democratic’ legitimacy to rule without being elected. Kim Il Sung’s popularity at this time was a result of the reforms carried out in the years following independence, which Kim was able to claim credit for. These social reforms included land reform which redistributed agricultural land from colonial landlords and collaborators to those who actually worked it. At a stroke North Korean industry was nationalized and Labour and Equality Laws were quickly enacted. These reforms meant that a huge majority of the population had some reason to be thankful for the work of Kim Il Sung and his colleagues. This inclusive nature of the new North Korean politics was the basis of the claim for ‘democracy’ in the DPRK.

From its inception and even before the DPRK was being made ready to survive in a hostile environment, its high level of militarization was a reaction to the circumstances with which Pyongyang was faced – the ideological enemy to the South. North Korea’s militarization was emblematic of the way in which North Korean politics and society were to be developed; “built on the Japanese colonial legacy of wartime mobilization, led by veterans of the guerrilla wars in Manchuria and China, and equipped and advised by the Soviet Union.”[43] At this early stage in their now more than 6 decade long rivalry it is beyond dispute that “North Korea was infinitely stronger – both militarily and politically – than South Korea, mainly because it was organized and unified to a far greater degree.”[44] While this strength, particularly military but also political, can be attributed to Soviet patronage, the organization and unity were primarily Korean in origin and implementation. The indigenous blend of Kim Il Sung’s top down management and his appeals for a new Korean Nationalism, in harmony with the bottom up, grass roots organisation of the People’s Committees were both popular and successful.

From a political point of view Kim Il Sung has often been portrayed as a Soviet puppet, and Juche as not new or even a stand-alone ideology, evidence for this point of view was clear in these early years of the DPRK. The constitution, enacted as the new state was proclaimed could clearly be viewed as the work of the USSR. However, while this is undoubtedly true the conclusion that some commentators have made; that this proves North Korea is no more than a puppet state, overlooks the regime priorities and pragmatic nature of Kim Il Sung and his colleagues at this crucial time. The elements of Juche ideology that were evident at this time (although Juche was not mentioned by Kim until later) were manipulated to ensure North Korea’s survival as an independent entity.

“The task of Kim was ultimately that of trying to remove or reduce those aspects of (Soviet) ideology (practice) that fitted Korean needs poorly, and thus to ‘Koreanize’ the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.”[45]

This period of North Korean development has been described as ‘politics first’. The most important aim was to promote loyalty to the regime among the masses, in order to ensure internal stability in what were to be difficult and uncertain times for the DPRK. This created the legitimacy which would later allow Kim Il Sung and Juche to mould the North Korean state, as circumstances and needs changed, almost at will.

Economic Success and Failure

“North Korea, once the peninsula’s industrial showcase, is now an industrial wasteland.”[46] The above quote is typical of those recent analyses concerned with the North Korean economy as economically the DPRK has variously been described as a ‘miracle’, as having a ‘rocket like trajectory’ and is now almost exclusively described as an economic ‘basket case’, demonstrating classic examples of the failure of a Stalinist, centralized economy. North Korea’s industrial base was originally established under Japanese occupation, the North’s wealth of raw materials contrasting it to the South’s abundant agricultural land. After liberation by the Soviets this existing base was ‘encouraged’ by Moscow rather than ‘stripped’ as many outside observers had predicted. These two factors enabled the DPRK to move quickly to establish a system of “economic planning [that] would be nationalist, the complete rejection of colonial Korea’s dependency on Japan and, while integrated into the Soviet economy, more a local-level imitation of Stalin’s ‘socialism in one country’ than an economic extension of the USSR.”[47] The irony being that communist production was dependent on the Japanese it sought to reject for its very existence. North Korean industrial capacity was dealt a huge blow by the UN’s bombing campaign during the Korean War, cities were flattened and power plants and hydro-electric dams were targeted. The destruction was so total that the American General in charge of bombing missions commented that ‘there were no more targets in Korea’.[48] Although this set the DPRK’s economy back significantly it also acted as a unifying event for the North Korean people. The population rallied around Kim Il Sung as his personality cult intensified and embraced the economic policies he promoted to raise economic activity from the ashes. Although the Korean War decimated the North, and with it the majority of its industrial capacity as well as a significant proportion of its agricultural output, economic production recovered to become the surprising success story written about by Joan Robinson and others in the 1960’s. This success provided the DPRK with a firm basis for limited autonomy within the Communist world, at this time Juche was without doubt achieving its aims. “Kim Il Sung’s strategy was successful. No other course could have laid a basis for future development, nor preserved the country’s independence.”[49] The link between economic success and political independence was of principal importance to the Juche ideology, and was pursued through its counterpart the Chollima movement. With success came confidence; “economic self-sufficiency has been accompanied by an increasingly bold assertion of self-identity in intra-bloc relations.”[50] However, this extended and significant period of economic growth was followed by a period of stagnation and ‘bottlenecks’ in production, “like other centralized command economies, North Korea had difficulty shifting from extensive to intensive growth and to the demands of a more complex economy.”[51] The current phase can be traced to the collapse of the USSR when the North Korean economy lost its main sponsor and took on the characteristics that define it now, catastrophic failure including periods of widespread famine and an unrivalled, and from a Juche point of view, humiliating dependency on overseas aid.

Economic planning based on the Soviet; Stalinist system began in 1947 when “the Soviet model of economic development was accepted with few if any, modifications. The emphasis … would be placed upon heavy industry and production related to defence.”[52] Post Korean War the Soviet model that had been initially followed was replaced by a Juche model. The economic path for the North was described by Kim Il Sung as a need to, “follow the line of giving priority to the rehabilitation and development of heavy industry and simultaneously developing light industry and agriculture.”[53] The Korean peasant based society combined with a shortage of agricultural land meant that agricultural concerns could not be marginalised as they had been in the USSR.

Economic plans of various lengths and success have dominated the North’s economic life since then. These plans have been allied with distinctive management systems said to have been personally invented by Kim Il Sung and inspired by his regular on-the-spot guidance sessions where the Premier would ‘bless’ a farm or factory with a visit and the benefit of his personal wisdom. “Comrade Kim Il Sung visited our plant, the Kiyang Tractor Factory, on eight occasions and had discussions with us, showing us clear-cut prospects of its development.”[54] These systems, the industrial Taean development method and its agricultural counterpart Chongsanri were popularised in the 1960’s and enabled the Party apparatus to be involved in economic decision making at every level. They were also used to give a sense of responsibility to workers and give even the most lowly operative a stake in the management of their factory or farm; echoing the union of top-down and bottom-up management that had helped bring the DPRK into existence. This Juche style of economic management was important for Kim Il Sung and the DPRK regime as throughout the state’s history, economics and politics have been closely linked; ultimately economic concerns have been subjugated to the political necessity of regime stability. In the eyes of the regime economic reform and liberalisation would lead to an unacceptable loss of sovereignty and dominance from external Global economic factors and trends. In this way we can see the power of Juche to influence the DPRK to follow what from the outside seems to be a path towards eventual collapse. If Juche’s success is in creating political stability, economic failure or at least the failure to enact meaningful reform can be viewed as its most significant negative side effect, a side effect which the regime has remained successfully isolated from. In order to see how and why Juche came to influence North Korean economic life to such an extent we will now turn to a more detailed examination of the DPRK’s industrial and agricultural sectors.

Industry

The three-year economic plan completed in 1956 brought early successes in post-Korean War reconstruction. The increasingly political unification of the population and the removal of many of Kim Il Sung’s opponents who had fled South during the War, combined with massive assistance provided by the USSR, China and other Socialist countries produced a barely believable boost to the North Korean economy. “Industrial production increased 42 per cent per annum; the production of coal increased from 700,000 tons in 1953 to 3,908,000 tons in 1956; electrical output increased from 1,017 million kwh to 5,120 million kwh; production of steel increased from 122,000 tons to 365,500 tons; and chemical fertilizer production increased from 4,000 tons to 190,000 tons.”[55] Although official figures cannot be trusted it is clear that a massive transformation was undertaken and this remains an impressive achievement. Building on this success the next (five year) plan marked the beginning of the process of building ‘the foundation of socialism’ along with a move towards the self-sufficiency that had long been a goal of the Kim regime but had not been proclaimed until now. From now on Juche would be the guiding principle of the DPRK.

In the economic sphere Juche and the Chollima movement worked hand in hand to inspire workers to ever greater exertions in the name of Kim Il Sung. In industry the main tool was the Taean management system. Described in official rhetoric as “the most superior socialist economic management system of our own way, which was created by President Kim Il Sung.”[56] In essence this system enables the Party to become directly involved at every stage of production down to the level of the individual worker. This emphasis on micro-management enables Committee members to ‘give priority to political work’ as in the DPRK following Kim Il Sung’s will, political ideology drives economic production, planning and structure, essentially Socialism in reverse. Taean ensures that the centrally planned aims of the economy are not deviated from; even within an individual’s personal sphere of production, individuality has been removed from the DPRK.

This emphasis on self-reliance and movement away from slavish devotion to the Soviet model meant increasing tensions in USSR/DPRK relations. Although this was partially managed by playing Moscow and Beijing off against one another it did mean a reduction in development aid to Kim’s regime, it also forced North Korea to increase spending on defence. This combination began to create problems for the North Korean economy during the 1960’s. The first seven year plan began in 1960 but had to be extended as a result of greater demand for military resources. “For the first time … North Korea experienced widespread slowdowns and setbacks,”[57] a continued emphasis on heavy industry has since then created ‘bottlenecks’ in the system that have never been addressed. The blistering early success of the centrally planned economy “made it difficult for the DPRK to alter its policies for a more complex stage of economic development.”[58] Although at first these problems were not apparent to the outside observer the inability or unwillingness to address them eventually led to an almost complete breakdown of the North Korean economic system. “In sum, there is not enough of anything: not enough raw materials, especially coal and iron; not enough electricity; and not enough transport, to ensure the inputs arrive on time and delivery dates for outputs are met.”[59] Attempts that were made to reform the economy, during the 1990’s under Kim Jong Il, were too little too late, the reasons for this shall be examined in the next chapter.

Agriculture

Agriculturally, as we have seen, North Korea was at a disadvantage from the outset. Separation from the ‘rice bowl’ of the South meant that throughout its history the DPRK would struggle to become self-sufficient in food. Despite its dependency on the South for food, agriculture was of significant importance to the regime, as has been mentioned previously Korea remained a peasant based society. As a result land reform re-distributing farms from landowners to those who worked the land, had been one of the first laws enshrined after liberation. It was unsurprisingly greatly popular among the general population and provided twin benefits to the Kim Il Sung regime. “Land reform had both a political and an economic purpose: winning support for the regime in the countryside and encouraging greater productivity and more systematic extraction from the agricultural economy.”[60] Although initial reforms were successful and popular they remained, within Communist ideology, incomplete. It was not until the post Korean War period of the mid to late 1950’s that individual farms were replaced by co-operativization. Both the importance of peasant support and the differences between North Korea and other Communist states of this time were shown by the efforts made by the regime to make this change consensual through inducements rather than force. Kim Il Sung and his colleagues recognized that their desire for independence of state action depended on a solid and devoted base of support at home and most significantly among North Korean peasants. As a result “the process of co-operativization was relatively peaceful and grain production remained stable during the co-operativization process.”[61]

Efforts to produce enough food for the nation to be self-sufficient and therefore ‘achieve’ Juche were co-ordinated by the Chongsan-ri movement, unveiled alongside and counterpart to the Taean Industrial Management system, Kim Il Sung’s personal visits for ‘on the spot’ guidance demonstrating the degree to which the regime was involved in every aspect of production, his position as national figurehead and infallibility, showing the mindset that would lead to eventual disaster. At some stages in its history North Korean agriculture has produced impressive results, during the 1980’s it was noted that the DPRK, “with half the workforce engaged in farming and less than half the crop area, it produces nearly as much food as South Korea.”[62] Unfortunately this marked a high point in agricultural production for the DPRK. Similarly to industry, farming has become increasingly intensive and fertilizer dependent; combined with this the growing need to create new agricultural land has led to the development of areas that are of only marginal suitability for farming. Intensive farming produces gradually lower yields over time, dependence on industry for ever greater supplies of fertilizer exposes agriculture to the same ‘bottlenecks’ that have plagued industrial production, and development of marginal land has left large areas of the North Korean countryside susceptible to landslides and flooding. These factors combined with extreme weather to cause mass famine throughout the 1990’s. Again in common with industry, the North Korean’s failure or inability to move from a policy of extensive to intensive growth in the agricultural sector, moved them from what was a promising position in their fight for independence to one in which they have come to rely heavily on outside assistance. This failure was compounded by two competing elements of the DPRK’s Juche strategy; massive military spending that drained resources from all other sectors, and a lack of foreign trade which could have supplemented the shortages and helped alleviate the bottlenecks in the system.

“The inward-oriented self-reliant development strategy and the associated import substitution-oriented strategy produced a high degree of interdependency between the industrial and the agricultural sectors and this interdependency was accentuated by the small size of the external trade sector… The consequence was widespread hunger, near starvation and general misery for the people of North Korea.”[63]

Juche Man

As mentioned above the Juche ideology worked hand in hand with Chollima – a rallying call for all members of the DPRK to push themselves to achieve ever greater results for the state, or more accurately, the regime. “The Chollima movement was not only aimed at increasing production, it was also aimed at remoulding man himself, transforming him into a good Communist who would sacrifice himself for the sake of the collective interest.”[64] Introduced in 1959 a few years after Juche, the ‘flying horse’ symbol quickly became ubiquitous as did the repetitive political slogans designed to both motivate and educate the masses. Despite claims of this initiative’s uniqueness both Chollima and its offshoots Taean and Chongsanri are modelled on the Stankhanovite campaign of the USSR, and Mao’s Great Leap Forward in China, movements designed to extract ever greater efforts from the regimes workers. The population has been repeatedly called upon to sacrifice themselves for the good of the state. As noted by scholars of North Korea for decades now, “the promises of a better life … stand in contrast to the realities of continuing sacrifice.”[65]

Chollima and Juche have been manipulated to affect every aspect of North Korean life. It is especially emphasised throughout the DPRK education system, and North Korean artistic productions are little more than “an instrument for implementing Party policy, for strengthening the totalitarian regime, and for promoting Kim Il Sung’s personality cult.”[66] Due to the DPRK’s isolation it has been impossible to judge the extent to which these slogans and the accompanying imagery are taken seriously by the population, for example “The World turns with Korea at its Axis!” [67] On the one hand increasing defections indicate disillusionment; however there seems to be little in the way of internal dissent. Whether this is a result of fear of capture by the security forces or wearied acceptance of the proclamations still being made over 50 years after the initiatives introduction, remains unclear. What is clear is that the regime continues to endure at the cost of the population it claims to represent, and at some point “the system will have to face, the conflict between the economic man – innately individualist – and the political man – strongly collectivist – both of which, directly or indirectly, it seeks to cultivate.”[68]

DPRK Foreign Relations

The complex relationships between the ‘self-reliant’ North Korea and its more powerful foreign allies has for many years been at the core of DPRK foreign policy. Underlying the economic system employed in the name of Juche ideology, while simultaneously demonstrating its inherently contradictory nature, is a huge programme of financial assistance from the DPRK’s allies. This aid or sponsorship demonstrates that Juche’s most important role is one of propaganda to provide legitimacy on the home front. Although the Kim regime has demonstrated impressive autonomy of action within the Communist world, it has never been genuinely self-sufficient. Throughout its history North Korea’s and Kim Il Sung’s personal sponsor was the USSR and its mostly eastern European satellites. Of course as has been noted above the DPRK has received much more than just financial assistance from the USSR, owing its very existence to Stalin’s troops. However the USSR’s rival both in the Communist World and with regard to North Korean patronage has been China. Over two million Chinese ‘volunteers’ turned the tide in favour of the DPRK when Kim Il Sung’s forces were on the verge of defeat during the Korean War, and this fact has been well remembered in North Korea. “The outbreak of the Korean War and the subsequent entry of the Chinese troops into the conflict signalled the end of the Soviet Union’s exclusive role in the direction of North Korean affairs and considerably increased Chinese influence.”[69]

Of course since the collapse of the USSR, China has emerged as Kim Jong Il’s only ally, his recent trips to Beijing in order (we think) to secure the position of his son and potential successor Kim Jong Un, showing that despite Juche’s stated aim of ending Korean dependence on ‘Great Powers’ Sadae[70] is alive and kicking. Despite this current dependence on China, during the period when there was more than one state willing to offer assistance, the DPRK proved remarkably adept at playing these two rivals off against one another to achieve a level of independence which was unparalleled among Communist states of similar size. The Sino-Soviet split of the early 1960’s played into Kim Il Sung’s hands, and despite frequent fluctuations in both Sino- and Soviet–North Korean relations he was able to extract increases in aid and assistance from both parties, and crucially avoid total alignment with either in return for Korean support in individual disagreements. “It was not until he [Kim Il Sung] clearly understood the implications of the Sino-Soviet dispute for North Korea … that he began to elaborate on the subject of Juche.”[71] This awkward yet well exploited situation demonstrates the genuinely pragmatic nature of Juche ideology, and the necessity of reacting to the ‘real’ circumstances which the DPRK found itself in rather than doggedly following the path to Socialism without nationalist deviation.

The Sino-Soviet split, as well as providing an opportunity for the DPRK to engineer increased independence from its Communist allies, also convinced Kim Il Sung of the need to seek allies elsewhere, and to do so on Korean terms, by spreading the word of Juche to other countries. During the 1960’s and 70’s Kim Il Sung gave regular interviews to foreign journalists and regularly entertained Heads of State, “he also financed the establishment of more than two hundred organizations in approximately 50 countries to promote his political ideas.”[72] The culmination of this effort was the Arusha Declaration made by Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere on 5 February 1967 in which he proclaimed that Tanzania would follow a path of self-sufficiency, this policy was inspired by Kim Il Sung’s Juche. The motivation for this investment was competition with the South, in this case with regard to their battle for legitimacy in the eyes of the International Community, legitimacy that Juche could not provide, its strong cultural and traditionalist aspects limiting its effectiveness to internal and indigenous legitimacy. At this time states were choosing only one of the Korea’s to represent the whole peninsula as the de-facto Government, and in a sense there was a ‘race’ to be legitimized through peer recognition, and this would ideally culminate in the victor joining the UN at the expense of its neighbour. The North’s connections with the Communist world and affiliation with the Non-Aligned Movement gave them some advantage initially however as noted by Barry Gills in his work Korea versus Korea, “North Korea’s domestic and foreign policies, left essentially unchanged, lost correspondence with the main trends in the international system.”[73] These ‘regime rigidities’ led to the DPRK being in global diplomatic terms, kept on the periphery. Now despite both states membership of the UN, few would argue that it is the Republic of Korea to the south that has won this particular ‘race’ and achieved legitimacy in the international arena.

V. Kim Jong Il and Developments in Juche

Kim Jong Il’s Rise to Power

Many on the international stage believed that the death of the Suryong Kim Il Sung in 1994 would herald the collapse of the Juche regime in North Korea. However, instead of a collapse or even measurable weakening, there was an almost seamless hereditary succession to the Eternal President’s son and heir, Kim Jong Il. The ‘Dear Leader’ had been groomed for power since the 1970’s and had held a string of high profile positions within both the Party and State hierarchy before his father’s death. As we have seen previously Kim Il Sung was able to legitimately claim his exalted position as Father of the Nation, through a combination of his Guerrilla experiences in Manchuria, popular policies and Soviet backing. In this section I will investigate how the regime and by extension Juche, legitimized Kim Jong Il’s leadership despite his lack of experience or fame. In fact the contrast between the two men and their leadership styles is stark: “Kim Il Sung was an imposing figure who had fought against the Japanese. His son is a small man with no military record and an aversion to making public appearances or speeches.”[75] However, these differences in style have not corresponded to great deviations in policy.

In effect Kim Jong Il owes his position to little more than excellent transition planning on his father’s part. An extension of Kim I lSung-ism was worship of Kim’s family, most notably his wife and mother, but by extension also his descendents. This ensured that Kim Jong Il would be revered by the population. However, more than this KIS was acutely aware that “the succession of leadership following the demise of a dictatorial Communist ruler has been the most troublesome question for all Communist regimes.”[76] Kim Il Sung feared that his legacy would be destroyed by revisionist leaders of a new and divergent regime. The Suryong had ruled long enough to see the same happen to his major sponsors Stalin and Mao, and Kim Jong Il’s ascendancy was designed to cement his father’s position in the minds of the North Korean population. Despite his apparent lack of merit Confucian traditions meant that there was no one else on whom KIS could rely on to continue the path of Juche to such an extent than his own son. Furthermore, for the same reason there could be no one else whom the North Korean people would trust as implicitly to step into the shoes of the Suryong. Whether Kim Il Sung expected this to be so successful that he would be able to keep his position as ‘Supreme Leader’ of the DPRK even after death is unknown, but this highly bizarre development fits in well with the appeal to the Confucian traditions that brought Kim senior to power initially, as well as serving as a constant reminder of Kim Jong Il’s links to ‘higher powers’.

Kim Jong Il’s own personality cult was begun on his behalf with the production of official ‘hagiographies’ detailing his life since birth and achievements. The mythical and spiritual nature of the cult surrounding the Kim dynasty can be exemplified by the story of Kim Jong Il’s birth, supposedly on North Korea’s most sacred mountain Mt. Paekdu, “as he came into the world a new star appeared in the sky, a double rainbow appeared … strange lights filled the sky and a swallow passed by overhead to pass on the news of his birth.”[77] In reality the ‘Dear Leader’ was born in Russia while Kim Il Sung and his guerrilla fighters were sheltering from the Japanese Army. The mythical version is no doubt thought of as just that by the Korean People, although their traditions dictate they will value the story despite or in part because of its mythical nature. Politically KJI remained hidden from view until references to a ‘Party Centre’ became widespread during the 1970’s. In 1980 the matter of the succession was settled with the unveiling of Kim Jong Il, loyal son, patriot and unparalleled Juche devotee, “The Juche idea is the precious fruit of the leader’s profound, widespread ideological and theoretical activities, and its creation is the most brilliant of his revolutionary achievements.”[78] In 1991 Kim was appointed to the position of head of the Korean People’s Army from which, on his father’s death, he was able to assume full control of the DPRK. Despite this control in Confucian tradition Kim Jong Il did not ascend to the highest role, General Secretary[79] until an appropriate mourning period of 3 years had been observed. What may have been interpreted from the outside as a power vacuum, was in fact the expected protocol within the unique Korean system. In fact the reality of the situation was that absolute power didn’t shift instantly. The truth of the matter is that “during the twilight years of Kim Il Sung’s life, actual authority began to move towards the Kim Jong Il line, with the advent of ‘co-leadership’, wherein the senior Kim reigned while the junior Kim actually ruled.”[80] Furthermore although Confucian traditions and Juche propaganda may have legitimized Kim Jong Il in the eyes of the population, it took what Jei Guk Jeon has described as a ‘balancing act’ for his leadership to remain unthreatened by internal rivals, during the early stages of his rule. These alternative power centres could have been one of his father’s former comrades in a senior position or a leader of the KPA. To counteract these threats, Kim Jong Il followed policies of inter-generational balancing between his father’s generation and his own followers, and a system of inter-agency balancing to ensure that no part of the DPRK’s state apparatus was able to concentrate too much power. “His strategic objective was two-pronged: on the one hand, it was to prevent the concentration of power in any particular agency; on the other, it was to induce competitive loyalty to the leader.”[81] These policies effectively managed possible threats from within the regime, while underlying Confucian values and indoctrinated Juche ideology facilitated acceptance by the populace. If any external state was hoping to unsettle the DPRK at this time the speed and success of Kim Jong Il’s assumption of power was surprising enough to de-rail any effort before it was begun.[82] More important than the titles that he has gained, is the fact that Kim Jong Il now has the power to interpret the Juche ideology to reflect the needs of the regime and the DPRK, as circumstances dictate. This has led to some changes that we will examine in more depth below, of note at this point however is that despite Confucian tradition Juche did not always favour hereditary succession, describing it as ‘feudal’ and backward. This interpretation was removed from official doctrine as the reality of Kim Jong Il’s ascent to power became clear, the ‘Dear Leader’ was no doubt glad that his father had previously demonstrated and therefore legitimized the pragmatic nature of Juche during his own reign.

Economic Reform: Real or imagined?

Kim Jong Il’s reign as leader of the DPRK coincided with the most difficult period for the state’s economy since the destruction of the Korean War. The ‘bottlenecks’ and inefficiencies mentioned above which had previously made running an effective economy more and more difficult, were by the 1990’s preventing any meaningful progress being made. From 1990 the DPRK suffered 9 years of negative growth, reducing what had seemed like a model of Socialist management to an internationally recognised catastrophe. Compounding this was years of famine that, although estimates vary, may have killed up to two million North Koreans. This period of economic failure was triggered by the demise of the DPRK and the Kim regime’s greatest sponsor the USSR. The immediate cessation of economic support meant that supplies of “about 30 percent of North Korea’s imported oil, was discontinued, thereby making most of North Korea’s factories virtually inoperative.”[83] Although as should be noted the North Korean economy appears to have recovered to a certain extent more recently, this has been largely down to a willingness of others to step in to replace the Soviet Union: China largely but also international aid from the South Koreans and the USA among others. This modern aid dependency has led to Kim Jong Il being portrayed as a beggar on the international stage, desperate to grab what he can to help the DPRK survive. However, it is incorrect to say that the regime has made no effort to help itself, just that those efforts which have been made have been failures or largely inconsequential. Real reform has come but not from the regime – most prominently grassroots reform is affecting the way North Korea operates, and these reforms operate under Juche’s radar. State directed reforms have led to attempts to obtain financial assistance from the international community through loans. These efforts failed as it became obvious that North Korea was unable to make repayments. Also Special Economic Zones were established to attract foreign investment, however a combination of poor management and state interference, meant any initial enthusiasm for the projects was short-lived. Most significantly, the 1st of July measures of 2002 were heralded as a new beginning for the State, bringing in Capitalist elements to the system for the first time, and releasing the central grip on power to devolve decision making to a regional level, at least to a certain extent. Even before these well publicised reforms, North Korean society had been forced to change to survive, the 1998 Constitution recognized the fact of already existing farmers markets which had sprung up from a grass roots level. These endeavours on the part of North Koreans at a local level, demonstrate that the conditions which allowed Communism to flourish initially have not been eroded by the centralisation of the DPRK economy. This movement was crucial in preventing more deaths through famine as the regime’s primary mechanism to feed people, its ‘State Distribution System’ “had ceased to function for most people.”[84] In fact the 2002 reforms could be seen as a state attempt to reassert control as this ‘shadow’ or black market economy continued to flourish. The existence of “a bottom-up marketization which the North Korean regime was unable to control”[85] threatened the very essence of Juche, reform was meant primarily to restore its position of pre-eminence, the welfare of the population was a secondary concern.

Since 2002 opinion has been divided over whether what has been perceived from the outside as reform is a genuine attempt at ‘opening’ or a cynical ploy to extract the maximum amount of international aid and goodwill as possible. A joint editorial by DPRK newspapers proclaiming the need to “manage and operate the economy in such a way as to ensure the largest profitability while firmly adhering to the socialist principles”[86] would appear to give state backing to change. The reforms enacted certainly seem to mark a paradigm shift in the regime’s approach to economic management, The July 1st measures include:

“A sharp increase in prices and wages; a revision of the price settlement method; delegating part of the authority of the central government to formulate economic plans to the subordinate regional offices; empowering factories and enterprises with autonomous management rights; the establishment of markets for raw materials; a strengthening of payment according to ability; and a radical overhaul of the social security system.”[87]

Although these reforms appear to be impressive, and have furthermore led to some real change in the way the Kim regime administers the state, “marketization remains partial. The state has eliminated neither planning nor political guidance … [and]… North Korea’s financial sector remains highly statist.”[88] Commentators, having taken stock of the reforms and what they mean in a real sense, have come to agree that these partial reforms are not intended to begin an economic opening along the lines followed by China or Vietnam, nor are political changes expected to follow as a matter of course. The regime has essentially done little more than acted to shore up its position of stability as the unrivalled power centre of the state, continuing to put its faith in Juche to provide the necessary legitimacy. Demonstrably, the Kim regime’s primary aim in economic policy is to “maintain the monolithic system, as constructed upon the Juche idea.”[89] This achievement of this aim has come at great cost to the North Korean people.

Juche after Kim Il Sung: Continuity or Change?

Since inheriting power Kim Jong Il has overseen changes to the DPRK’s political organisation known as ‘Military First’ policies. These amount to an admission that Juche’s effectiveness has been reduced, and that the foreign environment has become more challenging. Greater emphasis and investment has been placed on the military within North Korea, this is both an effect of and contributor to the economic collapse experienced throughout the ‘arduous march’ of the 1990’s. Kim Il Sung had maintained a system in which the military hierarchy was second to civilian authority, Kim Jong Il promoted the National Defence Council (of which he is chairman) to the position of primary authority within the regime. This move simultaneously increased hardship for those not involved in the military, and pushed civilian industry to the back of the queue when raw materials and inputs were being distributed for manufacturing purposes. It also came as a consequence of the same factors which caused economic collapse, withdrawal of sponsorship and climatic disaster meaning that “social and institutional structures developed in previous decades and their attendant patterns of legitimation could no longer be sustained.”[90] North Korea as it now exists has become the world’s most militarized society with spending on the armed forces as a proportion of GDP presumed to be at a very high level.[91]