The purpose of this dissertation is to investigate the influence of the media on the U.S. decision to withdraw from humanitarian operations in Somalia in 1994. The role of the CNN effect on the decision to withdraw is the main focus of research. Authors in the field presume that a correlation between falling media support and a continuing decline in public approval ratings caused Congress to pressure the Clinton administration to withdraw. This piece tracks congressional dissent independently in order to establish an alternative timeline of approval using research materials thus far overlooked by scholars in the field. As well as evaluating the various reasons behind falling congressional support for the deployment the paper also charts President Clinton’s position within the decision making process. The personal reasons for Clinton’s desire to withdraw troops are largely overlooked in current scholarship and these are threaded into the overall paradigm. The conclusion highlights the limits of the CNN effect as a theoretical framework for explaining media influence on foreign policy decisions. It instead emphasises the unique situational factors which influence policy.

1. Introduction

‘CNN is the sixteenth member of the Security Council.’[1] – UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali.

Following the end of the Cold War, the media has had more opportunity to criticise U.S. foreign policy as the old paradigm of ‘us and them’ is no longer applicable. With containment and proxy wars over, as well as the ideological battle between the two super powers, domestic media has become freer to highlight the inadequacies of foreign deployments without appearing unpatriotic or undermining the quest for global democracy. A network of worldwide correspondents and the ability to transmit images instantaneously across the globe has meant that the media has become ubiquitous in the development of major events; it is now ever-present. CNN (Cable News Network), for example, has a network of 150 correspondents in 42 international bureaux and 23 satellites.[2] The time between an event occurring and the public being informed has shrunk considerably. This is due not only to television but also through the internet which can now be accessed globally through mobile phones and laptops. The television is now just part of the process through which media saturates and creates a virtual hegemony over the social sphere.

The relationship between the media and the government is one of great intrigue. On one hand the press relies heavily upon government documents to source many of the stories which it covers. On the other, bringing large amounts of attention to an issue of the editor’s choosing can raise social awareness and inform the public. The role which news plays in foreign policy formulation is variable, and obviously situational. It is difficult to ascribe a quantitative figure to the amount of influence the media wields since it has been ingrained into the process of reporting and informing both politicians and the public alike. Instead, evidence needs to be collected relating to specific instances of union between the political stances represented by journalists, and policy decisions that appear to follow. Although the separation of cause and effect from sheer coincidence or common consensus is complicated due to the wealth of variables, there are several cases in which an influential relationship has been purportedly exposed.

To fully expand upon this idea, this paper will explore the relationship between media coverage and the decision of the Clinton administration to withdraw from Somalia in 1994. Retrospectively, the U.S. withdrawal from Somalia has been widely understood to have been caused by the public response and subsequent pressure to withdraw following the publication of negative representations of the conflict by the media. [3] This public pressure is claimed to have influenced members of Congress who subsequently forced an early withdrawal. The event which culminated in congressional pressure to cease operations in Somalia was the publication of images which depicted dead U.S. soldiers being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu. The role the media played in the decision to withdraw is what will be investigated. Evaluation of the perceived excessive media coverage which influenced public opinion will help test the validity of claims surrounding the CNN effect. The extent to which reporting was excessive or merely graphic will play a role in evaluating the persuasiveness of news. However, before the issue of Somalia is discussed, it is important to ground the argument in the theoretical framework of media power and influence.

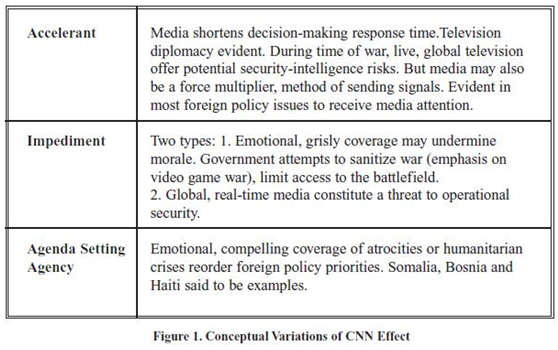

The technical term in scholarly discourse for the aforementioned relationship is ‘The CNN effect’ (alternatively ‘The CNN curve, or ‘The CNN factor’). There are several competing theories which try to extrapolate the relationship between the media and the formulation of domestic or foreign policy. Philip Seib claims the CNN effect is ‘presumed to illustrate the dynamic tension that exists between… television news and policymaking, with the news having the upper hand in terms of influence’.[4] Johanna Neuman’s competing and complementary theory states that when the airwaves are flooded with a foreign crisis policy makers are forced to address the issue. The administration has to address the public’s demand for action, subsequently ‘forcing political leaders to change course or risk unpopularity’.[5] Steven Livingston subcategorises these ideas into three distinct concepts:

As the majority of models deal exclusively with humanitarian intervention, hypotheses relating to these will be omitted. Therefore, those outlined by Livingstone as an ‘impediment’ and an ‘accelerant’ are directly relevant to the U.S. withdrawal and their theoretical schemas need to be concentrated upon.

The CNN Effect as an Impediment to Continued Operations

In 1993 U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Madeline Albright declared that ‘television’s ability to bring graphic images of pain and outrage into our living rooms has heightened the pressure both for immediate engagement in areas of international crisis and immediate disengagement when events do not go according to plan’.[7] The idea that grisly footage can undermine the morale of both troops abroad and the domestic masses has its roots in the Vietnam War. Iconic footage depicting the horrors of war, such as General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan’s public execution of a Vietcong officer[8] and the Vietnamese girl burned by Napalm,[9] rank as Number 16 and 1 respectively in the New Statesman’s most influential political photographs of all time.[10] Never before had the realities of complete journalistic freedom in a warzone resulted in such public condemnation of foreign deployment. Not only were the methods used by the military questioned, but also the whole justification for the war. Cynthia Carter and C.K. Weaver note that ‘this type of coverage helped to capture in stark visual terms the growing human costs of the war, and as such was praised – as well as blamed – for helping to erode public support for the conflict’.[11] In Livingston’s table it is also specified that, from an administrations point of view, limited access for journalists is a course of action that should be taken in order to minimise the graphic imagery of combat.

Since 1989 the Department of Defence has prohibited media coverage of American casualties being returned home in flag draped coffins.[12] The rationale behind such a ban is assumed to be that publicised images of dead soldiers will inevitably lead to an erosion of public support for any given conflict. This is more pertinent in deployments where vital U.S. interests are not widely believed to be at stake. Osama Bin Laden himself publicly commented on the reluctance of the U.S. to accept casualties. He said ‘when tens of your soldiers were killed in minor battles [in Somalia] and one American Pilot was dragged in the streets of Mogadishu you left the area carrying disappointment, humiliation, defeat and your dead with you.’[13] Actually showing graphic images of carnage is difficult in the United States due to censorship from the networks themselves. In reference to the Iraq war, CBS’s John Roberts said that ‘there are certain pictures that you just can’t show…you had to sanitize your coverage to some degree.’[14] Whether militarily enforced, or through network censorship, the real imagery of war rarely gets shown. When it does, in cases such as Somalia, public reaction to the mission overall is easily reversed if the goals of the deployment do not sync with vital U.S. interests. If casualties are not shown on television it can result in a video game war. The video game war was experienced in the Gulf[15] as the media were heavily censored and the majority of images shown were of smart bombs falling towards targets and skirmishes through night vision goggles. They rarely showed the realities and aftermath of conflict. It was only after success in the Gulf War, during which the media were granted limited access,[16] that George Bush could exclaim ‘By God, we’ve kicked the Vietnam syndrome once and for all!’[17] This censorship was a direct result of the impact of public opinion and exposure to graphic imagery during the Vietnam conflict. Carter and Weaver note that ‘the main lesson the U.S. military took away from Vietnam was that it would never again provide journalists with unlimited access.’[18] Unlimited access was available in Somalia because troops were officially under the banner of the U.N., and not the United States.[19]

The CNN Effect as an Accelerant to Policy Decisions

Livingston’s second subcategory is the CNN effect as an accelerant. This deals with the concept that an issue given media exposure is often put at the forefront of the agenda for the administration. From the administration’s perspective an issue covered heavily in the media is one that requires rapid clarification and/or policy to appease the questions posed by journalists and the general population. The result of this is that it forces the incumbent administration to work within much tighter time frames[20] to establish policy in order to placate the demand for a stated position. Administrations become inherently reactionary in order to survive within such a quick fire environment. Appearing hesitant or without a specified plan to combat which ever situation arises, an administration can seem weak and unfit to run the country. Working within Livingston’s framework, in Piers Robinson’s review of competing theories concerning the CNN effect, Robinson clarifies that when there is no policy following a recent event, and no agenda set, ‘journalists are able to frame reports in a way that is critical of government inaction and pressures for a particular course of action. This is when the CNN effect occurs’.[21] Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations builds upon this idea when he comments that ‘when there is a problem, and the policy has not been thought [through], there is a knee-jerk reaction. They [governments] have to do something or face a public relations disaster’.[22]

The extent to which either of these theorised models had an effect on the Clinton administration is one that can only be discussed after exploring the actual content and frequency of media exposure regarding Somalia further. This information needs to be correlated chronologically with the rise in congressional dissent for the operation. It is also important to closely follow Clinton’s reasons for withdrawal to fully investigate the extent of influence created by each factor. Major studies in the field fail to adequately assess what role the media played in creating congressional pressure to withdraw. A cause and effect relationship is assumed and the independent role of members of Congress is often over looked. The highly cited author Nik Gowing categorically states that ‘the gruesome images…of one dead U.S. Special Forces crewman being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu, plus video of the shaken Chief Warrant Officer Michael Durant forced – via congressional pressure – President Clinton’s announcement of a phased U.S. withdrawal from the Somalia U.N. operation.’[23] The minimization of congressional autonomy from media output will not be furthered in this paper as congressional materials such as subcommittee meetings, which have not been previously investigated, will be utilised to independently evaluate the course of congressional opinion. Studies that investigate the CNN effect in regards to Somalia fail to examine the various reasons for withdrawal in depth. The majority of focus is placed upon attempting to disentangle the competing theories. This piece aims to see what aspects of the CNN effect facilitated Clinton’s various reasons for withdrawal.

2. Somalia

American interest in Somalia dated back to the Cold War when it competed with the Soviet Union in the Horn of Africa for ideological allegiances. The U.S. had backed the traditional regime of Emperor Haile Selassie in neighbouring Ethiopia and the Soviet Union had forged connections with the Somalian Mohammed Siad Barre. Barre took power in Somalia after a coup in 1969. Post coup, Scientific Socialism became the cornerstone of policy[24] within the country. Barre depended on ‘substantial military aid through the mid 1970’s’ from the Soviet Union.[25] He undertook a brutal territorial war with Ethiopia in 1977 and later discovered that the Soviet Union had funded the Ethiopians. Outraged, he cut all ties with the Soviet Union allowing the U.S. to step in. The U.S. spent hundreds of millions of dollars on military and economic aid in Somalia throughout the mid 1980’s which only diminished at the end of the decade due to reports of large scale human rights abuses and the conclusion of the Cold War.[26] Rioting and demonstrations against Barre’s violent regime forced him to flee the country in January 1991. Warring factions who were clamouring for power plunged the country into civil war which resulted in the ceasing of all branches of civil government. Mogadishu, the capital city, became divided into clan areas and barricaded accordingly.[27] The ensuing struggle for power resulted in food becoming scarce. It was hoarded and guarded by each clan who used it as an instrument of power. To make matters worse a widespread drought hit Somalia in 1991 and hundreds of thousands of the nation’s poorest people were faced with famine.[28] With volunteer relief organizations unable to execute a huge aid operation the situation worsened. The plight of the Somali people gained media attention and eventually on April 24th 1992 the United Nations approved Resolution 751. The resolution established humanitarian relief operations under the banner of UNOSOM.[29]

The U.S. launched Operation PROVIDE RELIEF on August 15th 1992 to airlift supplies from Kenya in order to assist the humanitarian effort being implemented by the U.N. By the 28th of that month resolution 775 had been adopted by the U.N., which rose troop numbers to 3500, increasing to over 4000 by mid September.[30] The rise in troop numbers resulted in more extensive media coverage from U.S. news channels and newspapers. Between President Bush’s television address to the nation (December 4th) and the US troop landings (December 9th) the issue of Somalia began to saturate the media. It rose from a combined rate of 5.5 articles per day in The Washington Post and The New York Times between November 26th to December 4th to 15.2 articles per day between the 5th and the 9th.[31] Similarly, CBS coverage boosted from 3 minutes 30 seconds over the 21 day period that led up to Bush’s decision to offer troops to the U.N. to 85 minutes in just 5 days from the 4th.[32] Operation RESTORE HOPE on December 9th 1992 saw U.S. troops landing on the shores of Mogadishu. They were met by the glare of television cameras who had been allowed onto the beach to film the unchallenged amphibious assault. The New York Times highlighted how this bizarre scene resulted in spotlights and flash attachments giving away the Marine’s positions and interfering with night vision equipment.[33] This event encapsulates the amount of freedom the press enjoyed in Somalia. Although it was condemned as interfering with operations, the fact still remains the media were not only allowed, but told in advance, where the landing would take place. Public attention to the media saturation was slow to begin with. In the fall of 1992 only 30% of Americans followed the Somalia issue closely; however that number had vastly increased to 90% by January of 1993.[34] Between December 1992 and January 1993 public opinion towards the deployment was favourable, between 66-84%.[35] By this point U.S. troop levels were building up to their largest number for the operation. 28 000 U.S. troops were joined by the Unified Task Force (UNITAF) of 17 000 troops from 20 countries, orchestrated by the U.N.[36] Bill Clinton was inaugurated as President just six days before the shooting of a marine on January 26th which resulted in negative press. Theresa Bly notes that in the following days articles began to appear which questioned the U.S. policy in Somalia. They often cited the waste of tax payer’s money as a reason for dissent.[37] The sum required to enact OPERATION RESTORE HOPE initially requested by President Bush for 90 days deployment was $560 million.[38]

One of The New York Times articles which covered the shooting commented that the marine in question ‘was the third American slain in Somalia.’[39] Utilising the word ‘slain’ in both the article and its title is an example of how the use of evocative words can result in a negative tone being perceived by the audience. The article also outlined the positive effects of the humanitarian intervention but then notes that ‘events today demonstrated how slippery the distinction between the political and the humanitarian goals is becoming.’[40] Despite this wave of negative sentiment the administration’s policies relating to the operation did not change. Due to the lack of combat deaths in the first few months of 1993 media exposure faded. Peter Jakobsen tracked the trend and commented that in those months reporting of the issue on CNN fell sharply. Similarly, the amount of reporters on the ground in Somalia also reduced considerably.[41]

The U.S. move towards expanding its role in Somalia from purely a humanitarian standpoint to a nation building exercise can be seen in February, two months before OPERATION RESTORE HOPE was completed and UNOSOM II was adopted. In a congressional hearing regarding Somalia, Robert Houdek (Bureau of African Affairs) said ‘progress on the security and political fronts are closely interrelated’ and that ‘we have supported…building political reconciliation from the grassroots up.’[42] The expansion of political goals from a humanitarian effort to a nation building exercise is often cited as the administration overstepping its mandate. This in turn led to the erosion of public support for operations. A Gallup poll in December 1992 indicated that 59% of respondents believed the role of the U.S. should be limited to humanitarian relief.[43] Louis Klarevas notes that ‘the public [were] clearly supportive of humanitarian goals but less enthusiastic about… facilitating a long-term solution.’[44] Since the majority of the American public obtains its information on foreign policy deployments through the medium of television and newspapers, framing the continued Somalia engagements in a negative light altered the public’s perception of the situation. The importance of declining public opinion in regards to the withdrawal is fundamental to this paper. The role of the media in the withdrawal will be examined in more depth when all factors have been outlined. The significance of the role that the media plays in mirroring and expressing public opinion can be seen in the extent to which members of the administration regard the media as key in voicing collective opinions. The Pew Research Centre for the People and the Press found that ¾ of presidential appointees and 84% of senior executives regard the media as their main source of information pertaining to public opinion.[45]

The continuation of media coverage in Somalia increased with the completion of OPERATION RESTORE HOPE in April of 1993 and the implementation of UNOSOM II the following month. As the problem of mass starvation had been mostly alleviated through the actions of RESTORE HOPE, the U.N. mandate aimed at facilitating nation building through political reconciliation was enacted under the banner of UNOSOM II. US troop numbers fell drastically from 28,000 to 5000[46] as other nations supplied troops replacing those from the U.S. Congressional dissent for the change in tact can be seen from the remarks of Douglas Bereuter of Nebraska during a meeting before the Subcommittee on Foreign Affairs on May 27th. He said that the intended mission was for humanitarian purposes and was ‘not to restore order in a general sense, or it was not to remove arms from the combatants. The American people, I believe, want and expect U.S. forces to withdraw now that the mission of creating a safe environment for delivery of food has been implemented.’[47] David Shinn the State Department co-ordinator for Somalia commented that the quick reaction force deployed will be there ‘until sometime probably late summer, but that date is going to be event driven. And if things are much quieter… it could be an earlier departure. If things turn bad on us or the U.N. at that time, it could be longer than that.’[48] This shows that congressional support for the operation was not entirely solid as early as the end of May. It also suggests that theoretically the escalation of violence should warrant an expanded U.S. presence in Somalia and not a curtailment of forces.

The major incident which sparked an increase in media coverage of the mission in Somalia was the death of 24 Pakistani troops on June 5th. The troops were ambushed by General Aideed’s men. Aideed was head of the Somalia National Alliance which was one of the clan factions competing for political power in Mogadishu. The situation in Somalia was clearly escalating even though the humanitarian element of international involvement had ceased. The media had no restrictions from the U.N. as to what they could transmit or where they could go. CBS news correspondent Bob Simon claimed that the closest parallel he’d seen to Mogadishu’s freedom for reporters was Beirut in the l980s. He also claimed that access in Mogadishu was actually better than in Beirut. Between March 1993 and March 1994 nearly 600 journalists from 60 nations passed through Mogadishu to report on the U.N. operation and ‘benefited from the freedom to cover both sides of hostilities.’[49] The ability to document both sides of the conflict ultimately meant that the consequences of actions undertaken by the U.S. could be explored fully. If journalists shadow a particular group of soldiers they are far more likely to move away from the scene when hostilities cease. The aftermath can be overlooked as the troops are ushered on to their next objective. Freedom of movement to independently negotiate the streets of Mogadishu without restrictions allowed journalists to also document events from the perspective of Somalis.

According to Major David Stockwell the events that occurred on July 12th were a turning point in the operations. He, the chief United Nations military spokesman during the operation, believed that reporting of the mission to destroy Mad Abdi’s House (Aideed’s Lieutenant) was the first instance where the press purposefully minimised the official casualty figures presented by peacekeeping troops. The International Committee of the Red Cross put the death total at 75 whereas the U.S. claimed it to be only 13.[50] A possible reason for this, he believed, was the death of 4 western journalists who were covering the event and were killed by an unruly mob subsequently. Negative reactions within the media are clearly apparent as phrases such as ‘plunging Mogadishu back into the chaos’ the likes of which had not been seen since ‘before…[the] American-led military force intervened in December’ could be found in articles immediately after the event.[51] Opinion articles mirror this sense of discontent. Another example from The New York Times declares that ‘enough is enough’ and although ‘the original U.N. objective in Somalia was noble’ the situation has led to forces getting ‘bogged down in messy combat’. The ‘U.N. has neither the military means nor the political will to fight [such] a prolonged war.’[52] Interestingly a poll found 42% of the public were worried that the U.S. was getting in a quagmire.[53] Public opinion eroded during the summer months of 1993 with January figures stating 81% approval of the presence in Somalia which fell to 49% by the end of September.[54] By this time only 36% of the public believed the U.S. had the operation ‘under control’. 52% believed the U.S. was too deeply involved, the reasons behind this being that 69% believed the primarily concern should be the delivery of aid.[55]

The chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations said in late July that ‘there has been a good deal of debate in the Senate regarding the circumstances under which our forces should be participating in this U.N. campaign.’[56] He also stated that he continued to support U.S. involvement which creates a secure environment for ‘the provision of humanitarian relief’ but ‘questions remain as to whether a short run military action would really address the broader issues which keep Somalia a potentially destabilizing force in the Horn of Africa.’[57] Anti-withdrawal rhetoric can be seen from the statements of Senator Paul Simon (Chairman of the African Affairs Committee) who acknowledged that ‘there are those in the Senate now who say let us run, let us leave Somalia.’ He claimed that ‘hightailing it’ after ‘running into a few bumps along the road’ would be ‘absolutely irresponsible’ and it is essential that the U.S. joins other nations ‘in seeing to it that a government is established in Somalia.’[58] In the same meeting Senator Nancy Kassebaum voiced similar views expressing her ‘strong support for the U.N. in Somalia.’[59] Peter Tarnoff, the Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs, also stated the U.S. should see out UNOSOM II. This shows that although some members of Congress were voicing concern over the role of the U.S. in Somalia there was still support for continued operations. Despite the press starting to focus more consistently on the negative aspects of the issue, alongside the slow erosion of public opinion, there was still support in Congress.

Support for operations presented in newspapers decreased rapidly with the deployment of the U.S. Joint Task Force on August 22nd. The task force had the sole job of capturing Aideed for crimes committed against UNOSOM II forces. Theresa Bly found that immediately after the deployment all 36 articles researched in the L.A. Times had a negative slant towards operations.’[60]

The incidents of September 9th can be viewed as a potential point where Congress began to seriously question the deployment. The U.S. sent Cobra helicopter gunships to help protect Pakistani troops who had come under fire from 200 militiamen. The helicopter reportedly killed women and children alongside militia. Stockwell reports this news ‘created a maelstrom in Congress questioning…the mission in Somalia.’ Senator John McCain likened the event to the Ben Tre incident in Vietnam where a soldier was reported saying a village needed to be destroyed in order to save it.[61] On September 25th a Blackhawk helicopter was shot down using simple rocket propelled grenades (RPG’s) which resulted in the death of three U.S. soldiers. CNN had left Mogadishu several weeks before this incident as 5 of its Somali workers had been killed. The New York Times reported that there were only half a dozen journalists left in Mogadishu, none of which were American.[62] As the number of correspondents had plummeted there were no pictures of the reported ‘jubilant crowds of Somalis [who were] holding pieces of metal and what appeared to be burned flesh [as they] danced around the wreckage.’[63] The New York Times also reported that these deaths ‘provoked renewed calls from Congress for the immediate withdrawal’ of troops. Senator Robert C. Byrd said ‘we should bring the troops home.’[64] Senator Sam Nunn publicly criticized the mission and stated that the Clinton administration should focus the mission away from hunting down Aideed. Instead the administration needed to create a withdrawal strategy, otherwise Congress would force one.[65] Congressional pressure was mounting as the public opinion polls continued to decrease. The frequency of Somalia based articles in The Times ceased except for major events between late August and early October. These events were the deployment of Special Forces to capture Aideed in late August and the death of 3 soldiers in the Blackhawk attack described above. The final event was the death of 18 soldiers on October 3rd. The media’s role in continually shaping the opinion of the general public is dubious considering the inconsistency of The Times; however it is impossible to reach conclusions without the frequency of articles and news stories across the spectrum. This data is currently unavailable.[66]

Upon ascertaining information pertaining to the whereabouts of two of Aideed’s top lieutenants the U.S. Task Force Ranger unit undertook a daytime raid on October 3rd. After capturing 24 Somalis, while taking heavy fire, one Blackhawk helicopter was hit with an RPG and crashed. A second Blackhawk and two MH-60 helicopters were subsequently hit with RPG’s. Only one MH-60 managed to return to base. An attempt made to reinforce the troops protecting one of the crash sites was forced back to the airport due to heavy resistance. The relief column finally got to the troops at 01:55am. Whilst there they fought to release one pilot from the wreckage taking small arms fire and grenade attacks throughout the night. They managed to escape at 05:42am. 18 Task Force rangers had been killed and another 57 were wounded.[67] It is estimated that between 500 and 1500 Somalis had also been killed.[68]

In the following days images surfaced on television and in newspapers of dead American soldiers being dragged naked through the street. They were surrounded by cheering Somalis. Also gracing the front pages was the bloody face of the captured soldier Michael Durant. His picture was placed on the front of Time magazine with the headline ‘What in the world are we doing?[69] Public reaction was predictably negative; Daniel Fitzsimmons notes that in an analysis of 16 polls taken in the aftermath of the incident 60% of the public demanded an immediate withdrawal.[70] Bly corroborates this stating that immediately after October 4th approval ratings for the mission stood at 21%, half what they were the previous week.[71] In an analysis of 20 articles in The New York Times between October 4th and October 25th the amount of articles that had a negative slant towards operations in Somalia compared to those which were unbiased or in favour was 15:5. There was only 1 vaguely positive article.[72] The positive article came after the announced six month withdrawal and noted that Clinton ‘appeared to have quelled criticism’ which he had previously been inundated with. Members of Congress ‘praised the [withdrawal] announcement.’ The article distances U.S. actions from those of the U.N. which it claimed had ‘been bogged down in a bloody and futile search for the fugitive faction leader Mohammed Farah Aidid.’[73] It fails to mention that the U.S. was intrinsic and supportive of these actions until the events of October 3rd. The sole reason this article is positive in nature is because policy had changed and a planned withdrawal had been announced. The negative articles highlight that ‘young soldiers and marines return home not in triumph but in body bags’[74] and that Mogadishu is ‘anything but secure.’[75] Despite the trend that generally sees negative articles before the announcement of the withdrawal, with unbiased and less criticizing after, one article is still heavily biased on October 15th. Thomas Friedman comments that the administration will have to engage in the ‘murky politics and gray compromises it believes are necessary to stabilize the country.’ These will result in ‘a minimum level of political reconciliation that will allow the United States to withdraw without seeing an immediate collapse into chaos.’[76] This dissenting voice criticising the methods of ensuring a speedy withdrawal is alone amongst the majority of articles which praise the decision to bring the troops home.

After the events of October 3rd, public support for the operation had collapsed alongside any positive comments from the media. Congressional criticism was similarly strong. Although congressional dissent for the continued non-humanitarian operations in Somalia had been strong before the events of October 3rd, they intensified greatly in the aftermath. Democratic Senator Ernest Hollings claimed ‘it’s Vietnam all over again’.[77] Democratic Senator Bill Bradley said on the CBS News program Face the Nation ‘I think we ought to leave now.’[78] John Cushman claims that the mounting death toll and the images of ‘jeering Somalis celebrating amid the wreckage, have clearly influenced congressional opinion about the American presence there.’[79] Republican Senator Phill Gramm maintained that ‘the people who are dragging American bodies don’t look very hungry to the people of Texas’.[80] This comment highlights the clear discontent at the change in policy which led to the events of October 3rd. One issue that did prevent immediate withdrawal was that of hostages. Senator Robert Dole of Kansas mentioned that ‘If we had a vote today, we’d be out today,’ but ‘we can’t get out with hostages there.’[81] Clinton almost immediately forbade any further attempts at capturing Aideed and ‘compromised [with Congress] on a six month transition period’[82] to get the troops out. Congress then voted on H. Con. Res. 170 which directed him to remove troops by the agreed date of March 31st 1994. Despite an initial boosting of troops to facilitate the withdrawal, no further major events occurred between October 3rd and March 31st.

Although there is a correlation between the media output and public opinion ratings, the idea that congressional pressure arising from public discontent forced Clinton to remove the troops from Somalia alone is too broad. To fully understand the role of the CNN effect and the complex relationship of factors which resulted in the decision to leave Somalia more exploration is required. The role of President Clinton has been minimised thus far and his relationship with Congress has not yet been evaluated. Furthermore, the role of Congress which has been exaggerated as conforming to public opinion also needs to be expanded.

3. Conclusion

The decision to withdraw troops from Somalia could not have been due to excessive media coverage as by October 3rd 1993 there were only half a dozen Western journalists left in Mogadishu. The photo of the dead U.S. soldier being dragged through the streets was actually taken by a Somali.[83] The substantial troop fatalities and the impact of the graphic photos did however affect policy decisions. As Livingstone hypothesized in his breakdown of the CNN effect the saturation of the media with these images did negatively influence public opinion for the deployment as well as create congressional pressure. Although this is the case, it is important to be cautious in simply creating a supposed cause and effect relationship. To an extent graphic imagery did undermine morale for the conflict. The images created revulsion on the domestic front and highlighted how the operation was not progressing smoothly.

Public support for operations in Somalia had been declining ever since the initiation of UNISOM II. The change in tact towards a nation building exercise had created unease in a populous which had been told the mission had purely humanitarian purposes. Burk claims that ‘support for the mission had withered already in response to the changing mission before the firefight in Mogadishu.’[84] Both public opinion polls and media framing had reflected this shift. Although support in Congress was still evident during the transitional period between RESTORE HOPE and UNISOM II previous evidence portrays that undercurrents of dissent had already began to surface before October 3rd. Whether public opinion heavily influenced members of Congress to change their stance can only be properly evaluated on a case by case basis but it is very likely that it did in certain instances. Stephen Kull and Clay Ramsey found that despite African-American members of Congress generally being supportive of the deployment after October 3rd ‘members of Congress were perceived as shifting their positions in response to public outcry.’ Congressman Ronald Dellums was quoted saying ‘at the end of the day, [Black] caucus members are elected officials like everybody else. They respond to public opinion too.’ Also a quote from a congressional staff worker highlights that members of Congress were ‘overwhelmed with public revulsion – their own constituents’ revulsion at what happened.’[85] Despite the fact there is some truth to the persuasive effects of the media, it is presented in a monolithic fashion. Negative portrayals of the conflict in the press correlated with low public opinion polls, but congressional approval did take longer to diminish. The effect of the media is overstated. Once again external factors are overlooked.

Although it is easy to simply categorize members of the opposition party in Congress as being fickle to the whims of public opinion, the reality is that Democrats had a healthy majority in the House of Representatives during this period. Opposition was bipartisan. Ideological standpoints and personal beliefs that the operations had exceeded their mandate and that troops needed to withdraw were also vital in members of Congress’ dissent. McMaster believes that congressional anger was also ‘fueled by the apparent lack of coordination among the different members of the Clinton administration charged with policy toward Somalia.’[86]

The culmination of congressional opposition and low public opinion polls undoubtedly pressured Clinton into an early withdrawal. The graphic images of dead soldiers forced acceleration in policy from the Commander-in-chief. In this respect aspects of Livingstone’s hypothesis pertaining to policy acceleration do hold true, but Livingstone fails to factor in extraneous reasons into the model. Clinton’s motives for getting out of Somalia vary from the notion that he was simply forced into the decision by Congress and the lack of public support. Although Clinton had been in favour of the intervention initially,[87] by October of 1993 he had personal reasons for wanting to withdraw. The furore surrounding the military deaths in Somalia put into question the concept that with the Cold War over the U.S. could focus militarily on humanitarian missions. The U.S. could theoretically intervene in areas of the world where starvation or genocide was being committed. The events in Somalia had threatened the likelihood of Congress and the American public consenting to similar missions in the future. Clinton had both Bosnia and Haiti on the agenda, which he wanted the U.S. to play a role in. In his autobiography he writes that he ‘didn’t mind taking Congress on, but… [he] had to consider the consequences of any action that could make it even harder to get congressional support for sending American troops to Bosnia and Haiti, where far greater interests [were] at stake.’[88] The mission to save Somalia would go down in history as the decision of George Bush; Clinton would not get full credit. Another reason he wanted to cease operations was that just days before October 3rd members of Congress had made threats to initiate bills which would cut off funds for further operations. Even the threat of this action would reflect badly upon Clinton’s first inherited foreign deployment. Upon the successful completion of RESTORE HOPE the humanitarian aspect of the mission had been completed; this had been the aim of George Bush. Shifts in policy made it Clinton’s war and it was after this point that opposition rose and confidence was lost. The consequences of the decision to support a nation building exercise was that the situation had become open ended to some extent. The exit strategy would have taken considerably longer, at least until the next election, if support had continued to drop[89] from other U.N. Nations. This meant that the U.S. could have been left as the main contributors to an operation where no national interests were at stake. The reasons for remaining had greatly diminished. Clinton admits that ‘arresting Aidid and his top men because the U.N. forces couldn’t do it was supposed to be incidental to our operations there, not its main purpose.’[90] The wrong path had clearly been taken.

Congressional pressure and a clear lack of public confidence in the mission had a great deal of influence in the decision to withdraw. The graphic imagery presented within the media did force a knee-jerk reaction to the situation, but it did not alter policy alone, it simply produced an opportunity for Clinton to enact his changes. Jakobsen claims the withdrawal ‘was pushed through an open door’[91] as the administration had already decided continuation in Somalia was not viable. Even though Clinton battled Congress down from an immediate withdrawal to a six month transitional phase all dangerous missions were ceased.[92] The grace period was used to keep appearances in two main respects. It was important on the international stage to not show weakness in the face of a handful of military deaths. The idea that sustaining less than 20 casualties could result in a withdrawal of the world’s largest military force is not only embarrassing but also dangerous for future deployments. If a loosely collected militia could force a retreat it brings into question the nation’s commitments to its ideals; this is not politically viable. Similarly, abandoning the country immediately without some token form of removed political attempts at reconciliation creates the aforementioned impression. Clinton knew that if the troops stayed in Somalia for six months without incident then media coverage would diminish. The subsequent withdrawal would barely be reported and both national and congressional interest would have been drawn elsewhere by this time. Should Somalia descend back into chaos it would no longer be a primary national interest.

The concern raised about the CNN effect in a larger context is that theoretical models often paint the issues in black and white. Assuming cause and effect relationships between factors is dangerous because influence cannot be quantitatively valued. In cases such as Somalia those propagating the CNN effect over emphasize the effect of the media and minimise the influence of other factors such as Congress. Due to the wealth of overlapping influences that are unique to each operation the CNN effect should only be viewed as part of the puzzle and not the whole picture.

4. Bibliography

Adam, Hussein. ‘‘The International Humanitarian Intervention in Somalia, 1992 – 1995’’ in The Causes of War and the Consequences of Peacekeeping in Africa, Edited by Ricardo Rene Laremont, 171- 193. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2002.

Adams, Eddie. http://www.executedtoday.com/tag/nguyen-ngoc-loan/ (Last Accessed 20/10/10)

Albright, Madeleine K. ‘‘Building a consensus on international peace-keeping.’’ U.S. Department of State Dispatch 4.46, (1993): 789.

Authorizing the use of United States Armed Forces in Somalia: markup before the Subcommittee on International Security, International Organizations, and Human Rights of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Third Congress, first session on S.J. Res. 45, April 27, 1993. Washington: U.S G.P.O., 1995.

Besteman, Catherine. ‘‘The Cold War and Chaos in Somalia’’ in The State, Identity and Violence: Political Disintegration in the Post-Cold War World, Edited by R. Brian Ferguson, 285-300. London: Routledge, 2003.

Bin Laden, Osama Bin Muhammad. “Declaration of War against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places,” Hindukush Mountains, Khurasan, Afghanistan, August 23, 1996. Translation to English from Arabic by the Committee for the Defense of Legitimate Rights, originally published in Al-Quds Al-Arabi newspaper (London), http://www.comw.org/pda/fulltext/960823binladen.html. (Last Accessed 11/09/10)

Bly, Theresa. Impact of Public Perception on US National Policy: A Study of Media Influence in Military and Government Decision Making. Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, 2002.

Burk, James. ‘‘Public Support for Peacekeeping in Lebanon and Somalia.’’ Political Science Quarterly Vol. 114, No. 1 (Spring 1999): 53-78.

Bush, George. Funding for Operation Restore Hope : communication from the President of the United States transmitting request for transfer of funds within the Department of Defense in order to provide funding for the incremental costs arising from Operation Restore Hope, pursuant to 31 U.S.C. 1107. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1993.

Carruthers, Susan L. The Media at War. UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000.

Clinton, Bill. Address on Somalia. October 7th 1993. http://millercenter.org/scripps/archive/speeches/detail/4566. (Last Accessed 04/09/10)

Clinton, Bill. My Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

Cowley, Jason Ed. ‘‘The 50 Greatest Political Photographs.’’ New Statesman, April 5 2010, vii – xx.

Cushman, John H. ‘‘5 G.I.’s are Killed as Somalis down 2 US Helicopters.’’ The New York Times, October 4th 1993. (Last Accessed 31/11/10)

Fitzsimmons, Daniel. ‘‘Media Power and American Military Strategy: Examining the Impact of Negative Media Coverage on US Strategy in Somalia and the Iraq War.’’ Innovations: A Journal of Politics Vol. 6, (2006): 53-73.

Freedman, Des and Daya Kishan Thussu Ed. War and the Media. London: Sage, 2003.

Friedman, Thomas L. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Clinton Sending More Troops to Somalia.’’ The New York Times, October 7th 1993 (Last Accessed 31/11/10)

Friedman, Thomas L. ‘‘Mission in Somalia; Dealing with Somalia: Vagueness as a Virtue.’’ The New York Times, October 15th 1993 (Last Accessed 17/09/10)

Gordon, Michael R. ‘‘Mission to Somalia; TV Army on the Beach Took the US by Surprise.’’ The New York Times, December 10th, 1992. (Last Accessed 31/09/10)

Gowing, Nik. ‘‘Inside Story: Instant pictures, instant policy: Is television driving foreign policy?’’ The Independent, July 3 1994. (Last Accessed 28/09/10)

Gowing, Nik. ‘Real Time Television Coverage of Armed Conflicts and Diplomatic Crises: Does it Pressure or Distort Foreign Policy Decisions.’ Working paper 94-1 (June 1994). Cambridge, MA: The Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on Press, Politics and Public Policy, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

Herring, George C. ‘‘America and Vietnam: The Unending War’’- Foreign Affairs 70, No.5 (Winter 1991): 104-119.

Hoge, J.F. ‘‘Media Pervasiveness’’ Foreign Affairs 73, (1994): 136-144.

Jakobsen, P.V. ‘‘Focus on the CNN effect misses the point: The real media impact on conflict management is invisible and indirect.’’ Journal of Peace Research 37, No. 2 (March 2000): 131-43.

Jehl, Douglas. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Clinton Doubling U.S. Force in Somalia, Vowing Troops Will Come Home in Six Months.’’ The New York Times, October 8th 1993. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/08/world/somalia-mission-overview-clinton-doubling-us-force-somalia-vowing-troops-will.html?scp=6&sq=somalia&st=nyt (Last Accessed 08/09/10)

Jehl, Douglas. ‘‘G.I.’s pinned down in Somalia, not able, for most part, to patrol.’’ The New York Times, October 13th 1993. (Last Accessed 08/09/10)

Katovsky, Bill and Timothy Carlson. Embedded: The Media at War in Iraq. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, 2003.

Klarevas, Louis J. ‘‘The United States Peace Operation in Somalia.’’ The Public Opinion Quarterly 64, no. 4 (Winter 2000) pg 523-540.

Krauss, Clifford. ‘‘The Somalia Mission: The White House Tries to Calm Congress.’’ The New York Times, October 6th 1993. (Last Accessed 23/10/10)

Kull S, Ramsey C. The Myth of the Reactive Public. In Public Opinion and the International Use of Force, ed. PP Everts, P Isernia, pp. 205–28. London: Routledge, 2001.

Lacquement, Richard. ‘‘The Casualty-Aversion Myth’’ Naval War College Review, 57(1), (2004) 38–57.

Laidi, Zaki. The Super-Powers and Africa: The Constraints of a Rivalry 1960-1990. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Lewis, I. M. A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa London: Longman Group Ltd, 1980.

Livingston, Steven. ‘Clarifying the CNN Effect: An Examination of Media Effects According to Type of Military Intervention’, Harvard Research Paper R-18 (1997), Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Lorch, Donatella. ‘‘Hunted Somali General Lashes Out.’’ The New York Times, September 26th 1993. (Last Accessed 12/09/10)

Minear, Larry, Colin Scott and Thomas G. Weiss. The News Media, Civil War, and Humanitarian Action. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers Inc., 1996.

McMaster, Jeffrey. “The United States and Humanitarian Intervention After the Cold War: Iraq-Kuwait, Somalia and Haiti.” http://users.skynet.be/JeffreyMcMaster/research/humanit.pdf (Last Accessed 01/10/10)

Neuman, Johanna. Lights, Camera, War: Is Media Technology Driving International Politics? New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Pew Research Centre for the People and the Press. Washington Leaders Wary of Public Opinion; Public Appetite for Government Misjudged. April 17th 1998. http://people-press.org/report/92/washington-leaders-wary-of-public-opinion (Last Accessed 12/09/10)

Robinson, Piers. ‘‘The CNN Effect: Can the news media drive foreign policy?’’ Review of International Studies 25, (1999): 301–309.

Robinson, Piers. The CNN Effect: The myth of news, foreign policy and intervention. London: Routledge, 2002.

Ross, Michael. ‘‘Nunn Criticizes U.N. Hunt for Somali Warlord Aideed.’’ The LA Times, September 27th 1993. (Last Accessed 11/11/10)

Schmitt, Eric. ‘‘U.S. Vows To Stay In Somalia Force Despite An Attack.’’ The New York Times, September 26th 1993. (Last Accessed 11/09/10)

Seib, Philip. The Global Journalist: News and Conscience in a World of Conflict. Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.

Shattuck, J. ‘Human rights and humanitarian crises: Policymaking and the media.’ In R. Rotberg & T. Weiss (Eds.), From massacres to genocide: The media, public policy and humanitarian crises (pp. 169-175). Cambridge, MA: The World Peace Foundation, 1996.

Schemo, Diana Jean. ‘‘U.S. Attacks Rebels in Somalia; Marine is Slain Later.’’ The New York Times, January 26th, 1993. (Last Accessed 10/10/10)

Stewart, Richard W. United States Army in Somalia 1992-1994. Washington DC: Defense Dept., Army, Center of Military History, 2003.

Stockwell, Major David. Press Coverage in Somalia: A Case for Media Relations to be a Principle of Operations Other Than War. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1995/SDB.htm (Last Accessed 01/09/10)

Terry, Don. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; A Search for Words to Mourn Troops who Died in Somalia.’’ The New York Times, October 6th 1993. (Last Accessed 12/10/10)

Time Magazine. October 18th 1993. Front Cover. http://www.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19931018,00.html (Last Accessed 04/09/10)

United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on Africa. Recent developments in Somalia: hearing before the Subcommittee on Africa of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Third Congress, first session, February 17, 1993. Washington DC: U.S. G.P.O., 1993.

Usborne, David. ‘‘Somalia cuts Clinton down to size: Just as the President’s ratings take a turn for the better, the memory of his predecessors’ blunders return to haunt him.’’ The Independant, 10th October 1993. (Last Accessed 08/09/10)

U.S. policy in Somalia: hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, One Hundred Third Congress, first session, July 29, 1993. Washington: U.S G.P.O., 1994.

Ut, Nick http://web.mit.edu/drb/Public/PhotoThesis/ (Last Accessed 04/10/10)

United Nations Somalia UNOSOM I. The Department of Public Information, 1997. http://www.un.org/Depts/DPKO/Missions/unosomi.htm (Last Accessed 28/09/10)

U.N. Raids Somali Clan’s Base; Mob Kills at Least 2 Journalists.’’ The New York Times, July 13th 1993. (Last Accessed 12/10/10)

Wheeler, Nicholas. Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000

Wines, Michael. ‘‘Mission to Somalia; Bush Declares Goal in Somalia to ‘Save Thousands.’’’ The New York Times, December 5th 1992. (Last Accessed 10/10/10)

Withdrawal of U.S. Forces from Somalia. Markup before the Committee on Foreign Affairs; House of Representatives, 103rd Congress, First Session on H. Con Res. 170, November 3, 1993. Washington DC: US G.P.O. 1994.

‘‘Course Correction Needed in Somalia.’’ The New York Times, July 14th 1993 (Last Accessed 23/10/10)

5. Appendix

Articles Reviewed for Comment:

Opinion Piece. ’’Somalia: Time to Get Out.’’ The New York Times, October 8th 1993. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/08/opinion/somalia-time-to-get-out.html?scp=15&sq=somalia&st=nyt

Apple, R.W. ‘‘Clinton Sending Reinforcements After Heavy Losses in Somalia.’’ The New York Times, October 5th 1993.

Applebome, Peter. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Soldier on a Secret Mission now a Captive in a Spotlight.’’ The New York Times, October 6th 1993.

Cushman, John H. ‘‘5 G.I.’s are Killed as Somalis down 2 US Helicopters.’’ The New York Times, October 4th 1993.

Friedman, Thomas L. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Clinton Reviews Policy in Somalia as Unease Grows.’’ The New York Times, October 6th 1993.

Friedman, Thomas L. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Clinton Sending More Troops to Somalia.’’ The New York Times, October 7th 1993.

Friedman, Thomas L. ‘‘Mission in Somalia; Dealing with Somalia: Vagueness as a Virtue.’’ The New York Times, October 15th 1993.

Gordon, Michael R. with Thomas Friedman. ‘‘Details of US raid in Somalia, success so near, a loss so deep.’’ The New York Times, October 25th 1993.

Hanley, Robert. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Relatives Recount Dreams of 2 Killed in Somalia.’’ The New York Times, October 7th 1993.

Jehl, Douglas. ‘‘G.I.’s pinned down in Somalia, not able, for most part, to patrol.’’ The New York Times, October 13th 1993.

Jehl, Douglas. ‘‘Somali G.I.’s; They’re Bitter & Grousing.’’ The New York Times, October 13th 1993.

Jehl, Douglas. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Clinton Doubling U.S. Force in Somalia, Vowing Troops Will Come Home in Six Months.’’ The New York Times, October 8th 1993.

Kerry, Bob. ‘‘Not So Fast on Somalia.’’ New York Times, October 7th 1993. (Opinion Piece)

Krauss, Clifford. ‘‘The Somalia Mission: The White House Tries to Calm Congress.’’ The New York Times, October 6th 1993.

Krauss, Clifford. ‘‘The Somalia Mission: Congress; Clinton Gathers Congress Support.’’ The New York Times, October 8th 1993.

Lorch, Donatella. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Safety Concerns Limit the Capability of Reporters to Work in Somalia.’’ The New York Times, October 7th 1993.

Lorch, Donatella. ‘‘Somali General Denounces Further Peace Talks.’’ New York Times, October 6th 1993.

Smothers, Ronald. ‘‘The Somalia Mission: The Families; Anger and Confusion and Fort Benning.’’ The New York Times, October 8th 1993.

Terry, Don. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; A Search for Words to Mourn Troops who Died in Somalia.’’ The New York Times, October 6th 1993.

Whitney, Craig R. ‘‘The Somalia Mission; 2 Rangers Tell of an Ordeal Under Fire.’’ The New York Times, October 9th 1993.

[1] Larry Minear, Colin Scott, and Thomas G. Weiss, The News Media, Civil War, and Humanitarian Action (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers Inc., 1996), 4.

[2] Des Freedman and Daya Kishan Thussu Ed., War and the Media (London: Sage, 2003), 117.

[3] Theresa Bly, Impact of Public Perception on US National Policy: A Study of Media Influence in Military and Government Decision Making, (Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, 2002), 72.

– Nik Gowing, ‘Real Time Television Coverage of Armed Conflicts and Diplomatic Crises: Does it Pressure or Distort Foreign Policy Decisions,’ Working paper 94-1 (June). Cambridge, MA: The Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on Press, Politics and Public Policy, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 61.

– Stephen Kull & Clay Ramsey, The Myth of the Reactive Public In Public Opinion and the International Use of Force, ed. PP Everts, P Isernia, (London: Routledge, 2001), 205.

– Steven Livingstone, ‘Clarifying the CNN Effect: An Examination of Media Effects According to Type of Military Intervention’, Harvard Research Paper R-18 (1997), Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 4.

– J Shattuck, ‘Human rights and humanitarian crises: Policymaking and the media,’ in R. Rotberg & T. Weiss (Eds.), From massacres to genocide: The media, public policy and humanitarian crises, (Cambridge, MA: The World Peace Foundation, 1996), 176.

– Major David Stockwell, Press Coverage in Somalia: A Case for Media Relations to be a Principle of Operations Other Than War, 17. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1995/SDB.htm

[4] Philip Seib, The Global Journalist: News and Conscience in a World of Conflict (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002), 27.

[5] Johanna Neuman, Lights, Camera, War: Is Media Technology Driving International Politics? (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 15-16.

[6] Steven Livingston, ‘Clarifying the CNN Effect: An Examination of Media Effects According to Type of Military Intervention’, Harvard Research Paper R-18 (1997), Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. 2.

[7] Madeleine K. Albright, Building a consensus on international peace-keeping – US Department of State Dispatch 4.46, (1993): 789.

[10] Jason Cowley Ed., ‘‘The 50 Greatest Political Photographs,’’ New Statesman, April 5 2010, vii & xx

[11] Cynthia Carter, and C.K Weaver, Violence and the Media (Buckingham: Open University Press, 2003), 24.

[12] Richard Lacquement, ‘‘The Casualty-Aversion Myth,’’ Naval War College Review, 57(1), (2004): 41.

[13] Osama Bin Muhammad Bin Laden, “Declaration of War against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places,” Hindukush Mountains, Khurasan, Afghanistan, August 23, 1996. Translation to English from Arabic by the Committee for the Defense of Legitimate Rights, originally published in Al-Quds Al-Arabi newspaper (London)

[14] Bill Katovsky and Timothy Carlson, Embedded: The Media at War in Iraq (Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, 2003), 173.

[15] For more information on the video game war theory see: Jean Baudrillard and Paul Patton, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place (UK, Power Institute of Fine Arts, 2004)

[16] Major David Stockwell, Press Coverage in Somalia: A Case for Media Relations to be a Principle of Operations Other Than War, 17. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1995/SDB.htm

[17] George C Herring, ‘‘America and Vietnam: The Unending War’’ – Foreign Affairs 70, No.5 (Winter 1991): 105.

[18] Cynthia Carter, and C.K Weaver, Violence and the Media (Buckingham: Open University Press, 2003), 24.

[19] Major David Stockwell, Press Coverage in Somalia: A Case for Media Relations to be a Principle of Operations Other Than War, 17. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1995/SDB.htm

[20] Steven Livingstone, ‘Clarifying the CNN Effect: An Examination of Media Effects According to Type of Military Intervention’, Harvard Research Paper R-18 (1997), Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 2.

– J Shattuck, ‘Human rights and humanitarian crises: Policymaking and the media,’ in R. Rotberg & T. Weiss (Eds.), From massacres to genocide: The media, public policy and humanitarian crises, (Cambridge, MA: The World Peace Foundation, 1996), 176.

– Nik Gowing, ‘Real Time Television Coverage of Armed Conflicts and Diplomatic Crises: Does it Pressure or Distort Foreign Policy Decisions,’ Working paper 94-1 (June). Cambridge, MA: The Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on Press, Politics and Public Policy, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 1.

– J.F. Hoge, ‘‘Media Pervasiveness,’’ Foreign Affairs 73, (1994), 136.

– Philip Seib, The Global Journalist: News and Conscience in a World of Conflict (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002), 2.

[21] Piers Robinson, The CNN Effect: Can the News Media Drive Foreign Policy? (Review of International Studies 25, (1999): 308.

[22] Nik Gowing, ‘‘Inside Story: Instant pictures, instant policy: Is television driving foreign policy?’’ The Independent, July 3 1994,

[23] Nik Gowing, ‘Real Time Television Coverage of Armed Conflicts and Diplomatic Crises: Does it Pressure or Distort Foreign Policy Decisions,’ Working paper 94-1 (June). Cambridge, MA: The Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on Press, Politics and Public Policy, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 47.

[24] I.M. Lewis, A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa (London: Longman Group Ltd, 1980), 209.

[25] Catherine Besteman, ‘‘The Cold War and chaos in Somalia’’ in The State, Identity and Violence: Political Disintegration in the Post-Cold War World, Edited by R. Brian Ferguson (London: Routledge, 2003), 287.

[26] Ibid., 287.

[27] Hussein Adam, ‘‘The International Humanitarian Intervention in Somalia, 1992 – 1995’’ in The Causes of War and the Consequences of Peacekeeping in Africa, Edited by Ricardo Rene Laremont (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2002), 171.

[28]Richard W. Stewart, United States Army in Somalia 1992-1994. (Washington DC: Defense Dept., Army, Center of Military History, 2003), 6.

[29] Ibid., 6-7.

[30] Department of Public Information, Somalia UNISOM I, The United Nations, 1997

[31] Piers Robinson, The CNN Effect: The myth of news, foreign policy and intervention (London: Routledge, 2002), 54-55.

[32] Ibid., 55.

[33] Michael R Gordon, ‘‘Mission to Somalia; TV Army on the Beach Took the US by Surprise,’’ The New York Times, December 10th, 1992,

[34] Louis J Klarevas, ‘‘The United States Peace Operation in Somalia,’’ The Public Opinion Quarterly 64, no. 4 (Winter 2000): 524.

[35] Ibid., 526.

[36] Department of Public Information, Somalia UNISOM I, The United Nations, 1997.

[37] Theresa Bly, Impact of Public Perception on US National Policy: A Study of Media Influence in Military and Government Decision Making, (Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, 2002), 60.

[38]George Bush, Funding for Operation Restore Hope : communication from the President of the United States transmitting request for transfer of funds within the Department of Defense in order to provide funding for the incremental costs arising from Operation Restore Hope, pursuant to 31 U.S.C. 1107, (Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1993)

[39] Diana Jean Schemo, ‘‘U.S. Attacks Rebels in Somalia; Marine is Slain Later,’’ The New York Times, January 26th, 1993

[40] Ibid.

[41] P.V. Jakobsen, ‘‘Focus on the CNN effect misses the point: The real media impact on conflict management is invisible and indirect,’’ Journal of Peace Research 37, No. 2 (March 2000): 137.

[42] United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on Africa. Recent developments in Somalia: hearing before the Subcommittee on Africa of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Third Congress, first session, February 17, 1993 (Washington DC: U.S. G.P.O., 1993)

[43] James Burk, ‘‘Public Support for Peacekeeping in Lebanon and Somalia,’’ Political Science Quarterly Vol. 114, No. 1 (Spring 1999): 68.

[44] Louis J. Klarevas, ‘‘The United States Peace Operation in Somalia,’’ The Public Opinion Quarterly 64, no. 4 (Winter 2000): 526.

[45] The Pew Research Centre for the People and the Press, Washington Leaders Wary of Public Opinion; Public Appetite for Government Misjudged, April 17th 1998. http://people-press.org/report/92/washington-leaders-wary-of-public-opinion.

[46] William Clinton, Address on Somalia, October 7th 1993, http://millercenter.org/scripps/archive/speeches/detail/4566.

[47]Authorizing the use of United States Armed Forces in Somalia: markup before the Subcommittee on International Security, International Organizations, and Human Rights of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Third Congress, first session on S.J. Res. 45, April 27, 1993. (Washington: U.S G.P.O., 1995), 20.

[48] Ibid., 24.

[49] Major David Stockwell, Press Coverage in Somalia: A Case for Media Relations to be a Principle of Operations Other Than War, 17. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1995/SDB.htm

[50] Ibid., 27.

[51] ‘‘U.N. Raids Somali Clan’s Base; Mob Kills at Least 2 Journalists,’’ The New York Times, July 13th 1993.

[52] ‘‘Course Correction Needed in Somalia,’’ The New York Times, July 14th 1993

[53] James Burk, ‘‘Public Support for Peacekeeping in Lebanon and Somalia,’’ Political Science Quarterly Vol. 114, No. 1 (Spring 1999): 66.

[54] Ibid., 68.

[55] Ibid., 69.

[56] U.S. policy in Somalia: hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, One Hundred Third Congress, first session, July 29, 1993 (Washington: U.S G.P.O., 1994)

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Bly, Impact of Public Perception on US National Policy: A Study of Media Influence in Military and Government Decision Making, (Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, 2002), 60.

64 Major David Stockwell, Press Coverage in Somalia: A Case for Media Relations to be a Principle of Operations Other Than War, 18. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1995/SDB.htm

[62] Donatella Lorch, ‘‘Hunted Somali General Lashes Out,’’ The New York Times, September 26th 1993.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Eric Schmitt, ‘‘U.S. Vows To Stay In Somalia Force Despite An Attack,’’ The New York Times, September 26th 1993.

[65] Michael Ross, ‘‘Nunn Criticizes U.N. Hunt for Somali Warlord Aideed,’’ The LA Times, September 27th 1993.

[66] A substantial amount of analysis of newspaper articles has been independently undertaken, however, due to restricted funding and time constraints a greater amount was not feasible within this project.

[67] Richard W. Stewart, United States Army in Somalia 1992-1994. (Washington DC: Defense Dept., Army, Center of Military History, 2003), 19-23.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Time Magazine, October 18th 1993, Front Cover. http://www.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19931018,00.html

[70] Daniel Fitzsimmons, ‘‘Media Power and American Military Strategy: Examining the Impact of Negative Media Coverage on US Strategy in Somalia and the Iraq War,’’ Innovations: A Journal of Politics Vol. 6, 2006: 64.

[71] Bly, Impact of Public Perception on US National Policy: A Study of Media Influence in Military and Government Decision Making, (Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, 2002), 60.

[72] See Appendix for a complete list of articles analysed.

[73] Douglas Jehl, ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Clinton Doubling U.S. Force in Somalia, Vowing Troops Will Come Home in Six Months,’’ The New York Times, October 8th 1993.

[74] Don Terry, ‘‘The Somalia Mission; A Search for Words to Mourn Troops who Died in Somalia,’’ The New York Times, October 6th 1993.

[75] Douglas Jehl, ‘‘G.I.’s pinned down in Somalia, not able, for most part, to patrol,’’ The New York Times, October 13th 1993.

[76] Thomas L. Friedman, ‘‘Mission in Somalia; Dealing with Somalia: Vagueness as a Virtue,’’ The New York Times, October 15th 1993.

[77] Clifford Krauss, ‘‘The Somalia Mission: The White House Tries to Calm Congress,’’ The New York Times, October 6th 1993.

[78] John H. Cushman, ‘‘5 G.I.’s are Killed as Somalis down 2 US Helicopters,’’ The New York Times, October 4th 1993.

[79] Ibid.

[80] David Usborne, ‘‘Somalia cuts Clinton down to size: Just as the President’s ratings take a turn for the better, the memory of his predecessors’ blunders return to haunt him,’’ The Independent, 10th October 1993.

[81] Thomas L. Friedman, ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Clinton Reviews Policy in Somalia as Unease Grows,’’ The New York Times, October 6th 1993. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/06/world/the-somalia-mission-clinton-reviews-policy-in-somalia-as-unease-grows.html?scp=5&sq=somalia&st=nyt

[82] William Clinton, My Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 497.

[83] Major David Stockwell, Press Coverage in Somalia: A Case for Media Relations to be a Principle of Operations Other Than War, 28. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1995/SDB.htm

[84] James Burk, ‘‘Public Support for Peacekeeping in Lebanon and Somalia,’’ Political Science Quarterly Vol. 114, No. 1 (Spring 1999):77.

[85] Stephen Kull & Clay Ramsey, The Myth of the Reactive Public. In Public Opinion and the International Use of Force, ed. PP Everts, P Isernia, pp. 205–28, (London: Routledge, 2001), 207-208.

[86] Jeffrey McMaster, “The United States and Humanitarian Intervention After the Cold War: Iraq-Kuwait, Somalia and Haiti,” 57. http://users.skynet.be/JeffreyMcMaster/research/humanit.pdf

[87] Michael Wines, ‘‘Mission to Somalia; Bush Declares Goal in Somalia to ‘Save Thousands’,’’ The New York Times, December 5th 1992.

[88] William Clinton, My Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 497.

[89] Nicholas Wheeler, Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 198.

[90] William Clinton, My Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 498.

[91] P.V. Jakobsen, ‘‘Focus on the CNN effect misses the point: The real media impact on conflict management is invisible and indirect,’’ Journal of Peace Research 37, No. 2 (March 2000): 136.

[92] Douglas Jehl, ‘‘The Somalia Mission; Clinton Doubling U.S. Force in Somalia, Vowing Troops Will Come Home in Six Months,’’ The New York Times, October 8th 1993.

—

Written by: Daniel McSweeney

Written at: The University of East Anglia

Written for: Professor Geoffrey Plank

Date written: 12/10

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The ‘Chilling Effect’: Are Journalistic Sources Afforded Legal Protection?

- Local Peace Aspirations and International Perceptions of Peacebuilding in Somalia

- The Crime-Conflict Nexus: Connecting Cause and Effect

- An “Invitation to Struggle”: Congress’ Leading Role in US Foreign Policy

- A New Grand Strategy for a New World Order: US Disengagement from Sub-Saharan Africa

- US Counter-Terrorism and Right-Wing Fundamentalism