Chapter 1: Introduction

In Northern Ireland, and for those who study the conflict, there is an acceptance that addressing the problems that have plagued this region of the United Kingdom at the macro-level is insufficient (Knox and Quirk 2000: 50). However, it is the macro-level that has been the recipient of the majority of international and academic coverage since the 1994 paramilitary ceasefire (Hancock 2008: 218). This is in sharp contrast to the feelings on the ground that the conflict was being perpetuated by a minority of extremists on both sides (Knox and Hughes 1996: 90) and that grassroots initiatives were the most likely form of peacebuilding activity to bring about a viable solution to the chronic instability of this troubled region (Thiessen et al. 2010). A multi-modal approach has been taken to peacebuilding in Northern Ireland (Byrne 2001). At the elite level a consociotional model has been adopted in Northern Ireland, courtesy of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA), agreed in 1998, which has sought to remedy the structural causes of conflict and instability through widespread economic, political, and institutional reform. Meanwhile, the job of reconciling and transforming the relationship of the Protestant/Unionist and Catholic/Nationalist communities has been ‘outsourced’ to the voluntary and community sector through the Community Relations Council to encourage groups who may have been resistant to direct government funding to engage in community relations work (Hughes 2007, Aiken 2010). The segregation of the communities since the rioting that marked the beginnings of ‘the Troubles’ in the period 1969-1973 have been highlighted as one of the major issues that has led to the protracted nature of the conflict in Northern Ireland, and the deep-seated hostile attitudes between these two communities (Dixon 1997). Breaking down the negative stereotypes and prejudices held towards the ‘other side is, therefore, vital to the peacebuilding process in Northern Ireland, with the NGO community in a unique position to facilitate this process. With unprecedented access to resources and a large NGO sector, Northern Ireland offers a testing ground for grassroots peacebuilding initiatives to other societies attempting to emerge from protracted conflict (MacGinty et al. 2007).

Context

Northern Ireland has been at ‘peace’ now for 12 years. Overt conflict at the macro level has died down following the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) and the subsequent paramilitary processes of decommissioning. Peace, of some description, has been brokered by the leaders of political parties, paramilitary organizations and foreign politicians. A power sharing executive was agreed upon to ensure equality of representation and eliminate institutionalised sectarianism and bigotry. While the agreement consolidated the union between Northern Ireland and Great Britain in the meantime, the consent principle allowed for reunification with the Republic of Ireland should the majority wish it so. This of course means that, while the both sets of elite agreed to live with each other in relative harmony in the present, both still have contradictory plans for the Northern Irish state.

On the ground, however, the picture is very different. While Northern Ireland has supposedly entered a postconflict phase, violence remains a part of life for a large number of people. Splinter IRA groups such as the Continuity IRA (CIRA) and the Real IRA (RIRA) still operate to varying degrees in alienated and disenfranchised working class communities. Similarly, Loyalist paramilitary organizations were not subjected to the same decommissioning process as the IRA, and retain the ability to take up arms if deemed necessary. The events surrounding 12th of July this year demonstrate the level of frustration felt by the people of these interface working class areas. ‘Recreational rioting’ is an outlet for those who suffer sectarian intimidation, lack of education, no employment prospects and a lack of affordable housing. This situation was described by MacGinty et al. (2007) as ‘no peace, no war’.

Blaming and targeting the ‘other side’ becomes the norm in Northern Ireland. With almost every aspect of life segregated along sectarian lines, there is a great deal of fear, suspicion and mistrust for the opposing community, and little or no means of contact results in these prejudices remaining unaddressed. Duplicitous provisions and services, in addition to segregated education and housing means nothing is shared by the communities in Northern Ireland, with many fearing to tread into the territory associated with the ‘other’. Therefore, the NGOs based in the voluntary and community sector represent one of the only opportunities for sharing and contact in Northern Ireland.

Government Attempts at Reconciling the Communities

The failure of the power-sharing executive agreed to at Sunningdale in 1973 demonstrates the power of civil society to reject agreements imposed onto them[1]. The GFA has been referred to as ‘Sunningdale for slow learners’ showing that there is very little different in the make-up of this agreement, yet the GFA was endorsed by 70% of those who voted (Cochrane 2006: 262). The Community Relations Council (CRC) was set up in 1990 with the very intention of aiding community based organizations in preparing the ground for a peace agreement, contrary to the hostile environment that Sunningdale faced (Hancock 2008: 221). Cochrane and Dunn (2002) have suggested that the NGO sector was critical to the ‘Yes’ campaign[2] receiving such a high level of support and, thus, the GFA receiving a strong mandate.

The Northern Irish and British governments have implemented policies to effect reconciliation at the distributive level aiming to remedy the structural roots of the conflict. This resulted in an array of policies aimed at creating equality, for example Targeting Social Need (TSN) and fair employment legislation, as well as attempts to change attitudes through education initiatives, for example Education for Mutual Understanding (EMU) and Cross Community Contact Schemes (CCCS) (Knox and Quirk 2000). More recently, the government adopted the A Shared Future policy as a framework for creating good relations between the communities (Hughes 2007). Overall, the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) which implemented these policies in the 1990s was largely successful in addressing the material and structural inequalities that instigated the conflict between the communities (Aiken 2010).

However, peacebuilding scholars highlight that addressing structural and material inequalities is not enough to achieve intergroup reconciliation (Lederach 1997, Jeong 2000, Senehi 2002). These scholars believe that addressing the relationships between groups is at the crux of effective peacebuilding. The faltering start to the power sharing executive at Stormont showed that high levels of mistrust and antipathy between the political parties were enough to paralyse the Assembly between October 2002 and May 2007. These feelings of mistrust and suspicion at the political level have filtered down into society, where deep seated fear and hatred already existed (Aiken 2010).

At the societal level, these feelings of fear and alienation have never truly been addressed and have contributed to the protracted nature of the conflict. With little means of communication between the communities small incidents that could have been addressed have spiralled out of control and led to full blown riots, creating a self perpetuating cycle of fear and hatred. Hall (2003: 3) describes the events surrounding the rioting in 1969, which resulted in the segregation of the communities, and the fatal role of rumours and fear in this outcome: ‘In the absence of any contact between the communities, and no means of separating myth from reality, the downward spiral into violence had proven inexorable’.

Suspicion over government motives from within the communities and a small budget have combined to reduce the role of the government in the task of reconciling the communities at the societal level (Knox and Quirk 2000). Furthermore, in the name of social and governmental stability, a decentralised form of reconciliation and peacebuilding has been adopted instead of a tribunal or truth commission (Aiken 2010: 10). The reaction of the Protestant community to the Saville Report, and the reaction of both communities to the Eames-Bradley report, demonstrate how contentious an issue addressing the past remains in Northern Ireland (BBC News, 2010[d], see appendix I). These same community based organizations have also been involved in grassroots peacebuilding projects and initiatives designed to complement reconciliation work as a means of reducing violence in local communities. The work of these organizations was recognized in the GFA, with signatories pledging to support their work[3].

Research Questions to be Addressed

This project will aim to provide clarity over the role these organizations play in the postconflict context in Northern Ireland. Cochrane and Dunn (2002) provided insight into their role in the peace process, culminating with the signing of the GFA in 1998. This project will aim to build on this research by showing what these organizations are doing to help the prevention of a return to conflict in Northern Ireland. Research questions will include:

- What roles/services do the NGO community play/provide in Northern Ireland?

- Are NGOs having a lasting effect on the relationship between the communities?

- Does there appear to be sequencing to peacebuilding/development work?

- What stage of peace is Northern Ireland at?

- Are single identity projects a waste of funds?

- How does Peacebuilding work at the societal level?

- Is the NGO community making a worthwhile contribution to peacebuilding in Northern Ireland?

Methodology

A case study approach has been used as part of the research design for this project. The case study approach allows for the intensive study of a unit for the purpose of understanding a larger class of similar units (Gerring 2004: 342). The unit in this study is a NGO engaged in peacebuilding and reconciliation work in Northern Ireland. Firstly, Northern Ireland was chosen as it provides a ‘state-of-the-art’ laboratory of peacemaking and peacebuilding’ (MacGinty et al. 2007) that can offer instances of both success and failure to grassroots level peacebuilding initiatives in other societies attempting to emerge from conflict situations.

Furthermore, the organization was chosen for its relatively high standing in its local community, accessibility of information, and its willingness to participate in this project. This organization has been studied in previous research; therefore, secondary sources have been used to contribute to the primary materials. Originally, the project planned to compare two organizations in Northern Ireland. However, with limited resources for the second organization and limited space, a single case study was seen as the most viable option.

Semi structured interviews were conducted as part of this research. Interviewees were high level members of their organizations and therefore could provide an organizational response to the questions asked. This type of interview was used to allow interviewees to elaborate on their experiences, values, and attitudes (Devine 2002: 198). Previous research of a similar nature by Cochrane and Dunn (2002) found that quantative methods were inappropriate for this kind of study; therefore a purely qualitative approach has been taken. In accordance with the university ethics code, interviewees were asked for their consent to record the interviews and use this data in the research. All gave their consent, and all interviews have been used. Interviews took place between the 22nd and 25th of June in Belfast.

Evaluation is a problematic task in the context of postconflict societies. Downs and Stedman (2002: 43) point out that ‘it is difficult to think of an environment that is less conducive to the conduct of evaluative research’. The aforementioned authors underline the fact that it is almost impossible to disentangle the impact of one intervention given the number of variables involved in the implementation of any strategy. NGOs do not exist in a vacuum. They are inextricably linked to events at all levels in Northern Ireland. Therefore, this project will merely seek to clarify their role in a a very complex process rather than attempting to evaluate their impact on the political situation as a whole.

In addition, measuring the contribution of the NGOs to the peacebuilding process in Northern Ireland is equally difficult. A major cause of this is the lack of common understanding as to what is meant to be achieved. With peace in Northern Ireland meaning a number of things to a variety of people, there is no coherent ultimate aim for the work at the community level to be measured against. Instead, the contribution of the community sector, like peacebuilding itself, will have to be looked at as a slow and incremental process, whereby small steps represent progress, and results allow for more questions to be asked and new challenges to be faced. Cochrane and Dunn (2002: 151) explain it thus:

‘In reality, much of the most useful activity in this field is conducted invisibly and is not tied to particular events; it is often not appreciable when carried out, its value only becoming apparent in combination with other events and actions when viewed over time’

Chapter 2: Peacebuilding

2.1 Peacebuilding: Providing Some Conceptual Clarity

Peacebuilding has no universally accepted definition and, subsequently, there is no universal approach to building peace in societies affected by protracted conflict (MacGinty and Williams 2009: 99). Jeong (2005:2) points to the case of Namibia as the recognition of peacebuilding as a distinctive area of policy and operations .In discourse, the term first made an appearance in the ‘Agenda for Peace’ report by Boutros-Boutros Ghali in 1992. Distancing this new concept from previous generations of peace work, Boutros-Ghali emphasised the need to create a ‘new environment’ rather than merely bringing an end to violence (Diehl 2006: 108). In its most generic sense, peacebuilding is defined as ‘action to identify and support structures which will tend to strengthen and solidify peace in order to avoid relapse into conflict’ (Boutros-Ghali 1992 para. 21). This definition, of course, presupposes that there is peace to build upon (Darby and MacGinty 2003: 195).

Nevertheless, from this definition of peacebuilding one can deduce that other forms of conflict intervention like peacemaking, peacekeeping and conflict prevention all, to some degree or another, involve some form of peacebuilding. This, for example, may take the form of confidence building measures as part of a peace process (Ibid.). Indeed, some scholars use peacebuilding interchangeably with these concepts (Barnett et al. 2004, Diehl 2006, MacGinty and Williams 2009). This is particularly true of conflict prevention and peacebuilding as post conflict societies are extremely prone to falling back into cycles of violence, therefore the same technologies can be used for conflict prevention and peacebuilding (Barnett et al 2004: 35, Doyle and Sambanis 2006: 27).

Furthermore, Lederach (1997) adds to this by suggesting that peacebuilding occurs simultaneously with peacemaking and peacekeeping. Peacebuilding complements peacemaking in the sense that it underpins the elite brokered and manipulated agreements, and seeks to empower the communities which have been affected by war (Ramsbotham et al 2005: 215). However, peacebuilding is distanced from other concepts by virtue of the fact that in its original use the words ‘post conflict’ were added (Barnett et al 2004: 42). Overall, it is agreed that measures geared towards building peace can take place at any stage in a conflict. Peacebuilding, therefore, can take place at any phase of conflict, but usually gains momentum in the postconflict setting (O’Brien 2007: 120). Jeong (2005:3) emphasises this point by saying that the absence of violence is a prerequisite to the transformation of inter-communal relationships and reconciliation.

Besides its timing, peacebuilding is separated from these other concepts by virtue of the fact it seeks to achieve something much deeper than merely bringing an end to violence, or managing conflict. Instead, peacebuilding seeks to remedy the sources of conflict, preventing its recurrence by fostering the social, economic, and political institutions and attitudes that will stop the inevitable conflicts that occur in a plural society from developing into violence (Doyle and Sambanis 2000: 779). Contributing to this line of thought, MacGinty and Williams (2009: 107) put forward this definition of peacebuilding:

“Peacebuilding is the attempt to overcome the structural, relational and cultural contradictions which lie at the root of conflict in order to underpin the processes of peacemaking and peacekeeping.”

Based on this, we can use an example from Northern Ireland to demonstrate this point. While peacemaking eliminated violence through the decommissioning of paramilitaries, peacebuilding underpins this by attempting to tackle the ‘culture of paramilitarism’ through transforming paramilitary murals and reintegrating ex-combatants into society. Incidentally, this task was handed over to the NGO community, with the CRC providing NGOs with funds to transform local paramilitary murals. The definition above gives a relatively clear idea about what needs to be done, but questions remain. Who should participate in peacebuilding? How should it be done? How should limited funds be distributed? What timescale should be placed on these processes, if any? The debates surrounding these questions will be addressed in the following section.

2.2 Key Debates amongst Peacebuilders

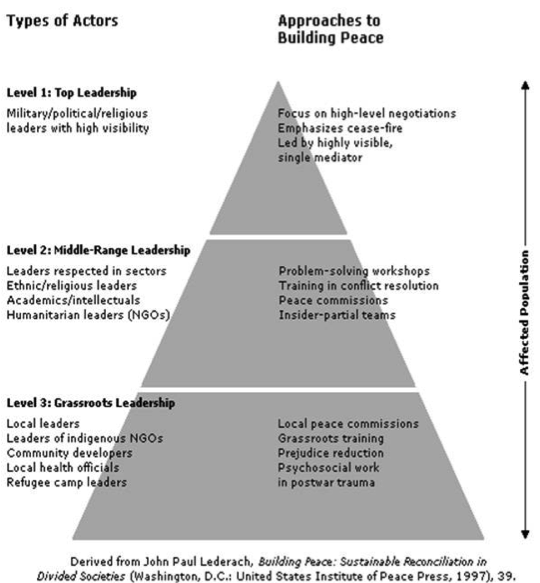

What peacebuilding ought to or does consist of remains a point of debate, but consensus is slowly emerging (Mendeloff 2004: 362).Roughly speaking, peacebuilding can be divided into two distinct schools of thought: top-down and bottom-up. These adopt diametrically opposed views on who should build peace in postconflict societies. Top-down (elite) approaches to peacebuilding focus on developments at the elite level, placing emphasis on the role of elite actors (high level politicians, located at the top of the pyramid in figure 1.) and the contribution of international organizations to peacebuilding (Ramsbotham et al. 2005). In Northern Ireland, the consociational model of government adopted as part of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) in 1998 would be regarded as an elite initiative to peacebuilding and conflict resolution with elites negotiating and sharing power in government (Dixon 1997: 2-3). In a lot of cases however, this form of intervention tends to be from external organizations (UN, NATO, OSCE) or states, who were initially involved in a peacemaking or peacekeeping capacity (Barnett et al. 2004).

Figure 1

Alternatively, It is argued that too often elites and decision makers dismiss the experiences and voices of those at the grassroots level, where the conflict has had the most devastating impact (Senehi 2000: 96). Bottom-up (grassroots) approaches highlight efforts at the societal level i.e. a form of conflict resolution developed by the affected people on the ground (Curle 1994, Lederach 1997, Last 2000). This school of thought places emphasis on mid-level actors and grassroots leaders and their roles in building peace, towards the bottom of the pyramid displayed in figure 1. It is argued that a vibrant civil society based on democratic participation and equality is the most effective path to peace. Grassroots peacebuilding, therefore, is focused on empowering those on the ground; people taking ownership of their situation and building from the ground up (Last 2000). This form of peacebuilding advocates a ‘village level’ approach, and the transformation of relationships between individuals and communities in war torn societies (Lederach 1997).

These two outlooks also differ on what they see as the source of conflict in, or between, states. Inevitably, this influences the type of work that is highlighted as necessary to remedy the causes of conflict in society. This disparity is also reflected in the NGO community in Northern Ireland, which is discussed below. The first point of view sees the source of conflict as state breakdown or the failures of legitimate state authority (Doyle and Sambanis 2000: 779). Therefore, it is regarded as crucial to rectify the institutional failures that led to state breakdown, addressing structural inequalities and economic, social and ethnic imbalances that led to conflict to begin with (Jeong: 4). This line of thought places emphasis on creating state institutions and political structures that can adequately address the needs of the population equally (Barnett et al. 2004; Jeong 2005; Doyle and Sambanis 2006).

However, creating structure is not necessarily enough. Structures can only be built on a solid piece of ground. It is therefore, necessary to ensure that the groundwork is done before, or in tandem with, the creation of structure. The behavioural approach places emphasis on the relationships between groups, and how the dysfunctional relationship creates conflict. Those who follow this line of thought tend to focus on the reduction of prejudice, truth and story-telling, problem solving workshops and positive forms of contact that can help foster reconciliation between groups (Senehi 2002). It is argued that reconciliation at the societal level is necessary to build relationships between former enemies in order to ensure the institutions and structures can function (Lederach 1997, Senehi 2000, Byrne 2001). Otherwise, as one interviewee said, it is akin to ‘building a skyscraper on an earthquake’ (representative of the CRC, 24th June 2010).

This, inevitably, raises questions over who should intervene in a conflict, or rather, who should build the peace. One set of scholars see the people from within the conflict as the problem, while outsiders are brought in to help bring about a solution (Ramsbotham et al. 2005: 222). This position claims, therefore, that any actors intervening in a conflict must be ‘outsider impartial’ in order to help build peace (Curle 1971: 173[4]). The rationale behind this argument is that those involved in the conflict are extremely unlikely to trust one another and therefore cooperation becomes impossible between them (Doyle and Sambanis 2006: 66).

On the other hand, some scholars (Curle 1994, Lederach 1997, Last 2000, Senehi 2000) argue that people involved in the conflict should be viewed as resources and, therefore, should be used to help build peace in the conflict zone. The idea behind this is that there can be no conflict transformation without a ‘change of heart’ (Curle 1994) from those on the ground. This change of heart must be natural, it cannot be imposed (Hamber and Kelly: 9), and therefore, helping the affected people to build relationships is seen as the only way to achieve this. In addition, local people may come to reject state institutions or agencies if they are not linked to the communities they are governing (Lederach 1997). Last (2000: 89) uses the example of the police to highlight the fact that they cannot be effective unless they are linked and sensitive to the communities they police.

One need only look at the example of the attitudes of the Nationalist community to the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) to understand the problems this poses. The perceived poor treatment of the Catholic community by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) has left a legacy that the PSNI will struggle to overcome. This could be said to have prolonged and exacerbated the activities of the paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland. Feeling that there was no safeguard for the community against potential attacks by the ‘other side’, paramilitary activities and policing have been accepted as the communities feel they may be needed to address identity based fears (Cavanaugh 2000: 76). This is an areas where NGOs have sought to become involved with Families Against Intimidation and Terror (FAIT) lobbying and campaigning against paramilitary punishment beatings and intimidation against the civilian population (Cochrane and Dunn 2002: 14).

Furthermore, individuals and groups from within the conflict setting involved in building peace should be encouraged to form horizontal relationships in order to build what Lederach (1997) calls a ‘peace constituency’. He argues, peace can only be sustainable if there is contextualized participation by those who have been most affected by the conflict i.e. those at the societal level (Ibid. 107). Lederach (Ibid.) and Last (2000) extend this line of thought by adding that external interventions are invariably brought in on a temporary basis, limited to the duration of their mandate. When that mandate is completed, their expertise and services are lost and there is, thus, increased likelihood that violence will resume.

The only way peace will be sustainable is if measures taken to build the peace are rooted within the local people and their culture. In this sense, a mandate approach has very limited applicability to peacebuilding activities. Nevertheless, timeframes are a point of contention between scholars with some (Paris 1997) arguing that the average mission length should be extended[5]. Others (Curle 1994, Lederach 1997, Last 2000) argue that viewing peacebuilding as a long term process of learning and outcomes is more productive way of assessing projects and initiatives. It is impossible, at some levels, to measure the progress a society has made (Hamber 2003), a point discussed further below. Given Northern Ireland’s location within the United Kingdom, intervention in Northern Ireland has been a process rather than a mandate approach.

When a mandate is complete, peace has not necessarily been achieved. In most cases, it is assumed that peacebuilding has achieved its task when a society emerges from conflict and manages to form a viable state and a new government (Jeong 2005: 2). In a number of examples, little attention was paid to the type of government or society that was built or took power in the wake of a conflict. This has inevitably led to complications with regimes in the likes of Rwanda and Cambodia. Some scholars argue that democracy provides a means of promoting a civic identity which offers an alternative to ethnic identification which may drive conflict (Jeong 2000: 118). However, others argue the imposition of a Western free market democracy can often cause instability in postconflict situations by pitting groups in competition against one another (Paris 1997). In societies where relationships are viewed in zero-sum terms, such as Northern Ireland, this can easily reignite conflict.

Moreover, solutions such as partition are said to hardly provide the ‘clean-break’ their advocates suggest (Darby and MacGinty 2003: 195).That the roots of the conflict in Northern Ireland can be traced back to the partitioning of the island in 1921 adds credence to this argument (Cochrane and Dunn 2002: 51). Similarly, the construction of an authoritarian regime creates more problems than it solves in the long run (Paris 1997: 58).This final point of debate in the literature relates to the concept of peace, what this means in postconflict societies, and what peacebuilding should ultimately seek to achieve if it is indeed designed to prevent societies from a return to violence.

Last (2000) proposes the requirements listed in Table 1 (see Appendix II) as the four basic components of any peacebuilding mission: security, government, relief and development, and reconciliation. Peacebuilding interventions of any description must address the underlying issues of conflict on all of these fronts. However, there is no single actor who has all the capabilities necessary to address the challenge of peacebuilding at all levels. In the case of Northern Ireland, the job of reconciling the communities has been ‘outsourced’, in a sense, to a collection of local government, civil society and community actors (Aiken 2010: 22).

2.3 Grassroots Approaches to Peacebuilding

While top-down peacebuilding initiatives can create equality and harmony in terms of service delivery, for example, housing, equal levels of employment, and this can measure the ‘success’ of society in terms of economic output and the performance of the economy, these approaches lose sight of the fact that other levels exist within society (Hamber 2003: 229). These include individual subjectivity, identity, emotionality, and the psychological impact of actual, or threatened violence against individuals or groups. Furthermore, in cases where peacebuilding is facilitated by outside agencies and international organizations there can be a lack of key peacebuilding skills such as language, cultural awareness and the ability to build relationships between former enemies (Last 2000: 87). A grassroots approach is, therefore, advocated for certain aspects of peacebuilding that cannot be addressed by outsiders, whether they are foreigners or elites.

The rationale behind peacebuilding from below is that many small interactions between people that help to rebuild relationships will multiply the chance that cooperation will take hold and spread (Ibid. 93). Senehi (2002: 46) builds on this by claiming that conflict interventions directed at one factor can affect other factors as well. In order for this to happen, there must be reconciliation between former enemies at the societal level (Lederach 1997). Southern (2007: 177) and Senehi (2002: 52) have argued that the experience of continual unhealed wounds and the enduring memory of conflict prevent the building of trust between communities and instead generate alienation. This in turn, serves to harden positions and make the difficult task of resolving conflict with ethnic or social roots even harder. Inevitably then, there must be a process whereby groups acknowledge the past (Lederach 1997: 26).

How do we address this difficult past then? At the grassroots level, particularly in poor societies with the memory of war fresh in their minds, this is no easy task. One means of doing so, advocated by scholars of peacebuilding (Senehi 2000, 2002) and social capital (Putnam 2000) alike, is storytelling. This form of intervention can help people of any background together to articulate and acknowledge the emotional trauma that they or another person have suffered in the past. Open to all people, this is cited as an excellent form of building trust, shared norms, and shared meaning between people of any background (Putnam 2000, Senehi 2002).

Acknowledging the past can, however, be extremely difficult in a society marred by protracted ethnic conflict. In some cases, it may be just as likely to open old wounds and traumatise an individual once again, or serve to highlight differences between people, than help the healing process (Mendeloff 2004). This is why storytelling must be constructive, as opposed to destructive (Senehi 2002). The most high profile example of this type of process would be the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. A similar type of procedure has been mooted for Northern Ireland but to this day little progress has been made on this issue due to how potentially divisive the subject of the past is, while politicians refuse cooperate with such an investigation as it may weaken their positions (Hamber 2003). However, research conducted by Aiken (2010) suggests that socio-emotional reconciliation in Northern Ireland can only be carried out through local decentralized initiatives.

The past, therefore, has a large influence on how groups interact with one another in the present, particularly between those who have had the worst experiences. To build sustainable trustworthy relationships in the present there must be an absence of violence. To aid the police and military in this aim there must be partnerships formed with local actors to provide conflict prevention at the lowest level (Last 2000). While the police and military can help to eliminate violence and build trust and networks, social capital[6], between former enemies to begin with, ultimately the local people have to take over this role themselves (Ibid. 93).

Linked to this, Lederach (1997: 24) argues that peacebuilding must move away from statist diplomacy by providing solutions that are rooted in and responsive to the experiential and subjective realities shaping people’s perspectives and needs. In these terms, peacebuilders must be aware of the needs and fears of the people on the ground in order to create an environment conducive to building trustworthy relationships between former enemies. Reconciliation, therefore, must be holistic in its approach to reconciling ethnic groups in conflict. Aiken (2010) provides a basic categorization of reconciliation processes: socio-emotional reconciliation, instrumental reconciliation, and distributive reconciliation. Questions remain, however, over the sequencing of these initiatives.

In addition, with the past and present renegotiated, some scholars argue envisioning a future of interdependence (a shared future in the case of Northern Ireland) is crucial to the process of reconciliation. This potentiality provides former adversaries with a common goal for moving into the future which Hamber (2003: 230-231) regards as the first step towards creating shared norms, values, and the negotiation of a new common identity. This common identity is a shared Northern Irish identity, making a break from one community trying to be ‘more British than the British’ and the other being ‘more Irish than the Irish’ (representative of the CRC, 24th June 2010).

2.4 The Elimination of Violence and the Building of Peace in Northern Ireland?

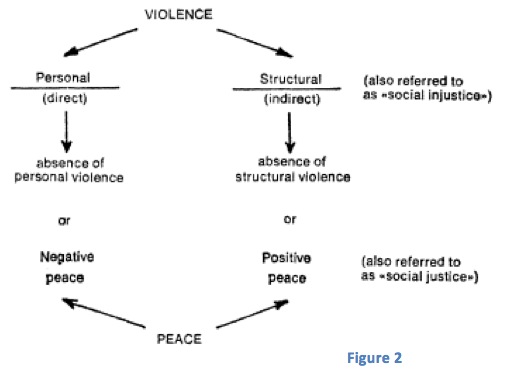

The manner in which a conflict is ended undoubtedly has a large bearing on a society and how it looks after war. There are a number of ways a conflict can end, ranging from outright victory of one side, to the separation or secession of a region from a state. Inevitably, this outcome has a causal effect on peacebuilding and the potential for the renewal of violence, for negative or positive. If, for example, there is outright victory for one side over another, oppression may be used as a tool to prevent the outbreak of violence by those who suffer from social injustice. Yet, there is peace, of some description in this society. Equally, segregation may cause temporary peace, but the long term potential for violence is heightened by the creation of a polarized society (Doyle and Sambanis 2006: 49). Galtung (1969) defined peace as ‘the absence of violence’. However, he argues that under this definition ‘highly unacceptable social orders would still be compatible with peace’ (Galtung 1969: 168).

With the definitions of both violence and peace being so interwoven we cannot understand one, in all its forms, without understanding the other. Violence does not necessarily have to be immediately manifest to exist in society. Instead, Galtung (1969, 1990, 1996) offers three interdependent forms of violence: physical (direct) violence, structural (indirect) violence, and cultural violence. Physical violence relates to actual acts of violence whether it is assault or the threat to do so. Structural violence results in violence being inherent in a system through uneven distribution, inequalities and marginalization, while cultural violence serves to legitimize the other two by being embedded in culture (Galtung 1990). Overall, Galtung argues that violence is anything ‘which increases the distance between the potential and the actual, as that which impedes the decrease of this distance’ (Galtung 1969: 168).

What, then, does peacebuilding seek to achieve? Doyle and Sambanis (2006: 23) offer this explanation:

“The aim of peacebuilding is to build the social, economic and political institutions and attitudes that will prevent the inevitable conflicts that every society generates from turning into violent conflicts.”

This view, of course, sees conflict as inevitable in society. While this may be, particularly in plural societies (Doyle and Sambanis 2000: 779), this suggests that the ultimate aim of peacebuilding is not necessarily to create a positive form of peace; rather, it is merely conflict prevention[7]. This type of society would fall under the category of negative peace, where physical violence is absent, but forms of structural and cultural violence remain.

What Galtung offers is a deeper meaning of peace, one that replaces penetration with dialogue, segmentation with integration and the removal of violence from language, art, law, and ideology (Galtung 1996: 32). What this means, in a crude manner, is not merely creating a society where there is ‘no more shooting’, but creating one where there is ‘no more need for shooting’ (Arnson and Azpuru 2003: 197). This type of society is characterised by positive peace by virtue of the fact that all forms of violence are absent. The bedrock of such a society, Curle (1994: 103) argues, is built on ‘impartial compassion, non-violence, human rights, and social justice’.

Galtung (1996: 32) affirms that positive peace is the best protection against violence. This requires the elimination of all forms of violence as ‘violence of any kind breeds violence of any kind’ (Galtung 1990). Therefore, if the ultimate aim of peacebuilding is to avoid a return to violence in postconflict societies, building a positive form of peace must be seen as the most effective way of achieving this end. Peacebuilding in any conflict setting must, in that case, take a multi-modal approach to address the inequalities and violence inherent in these systems.

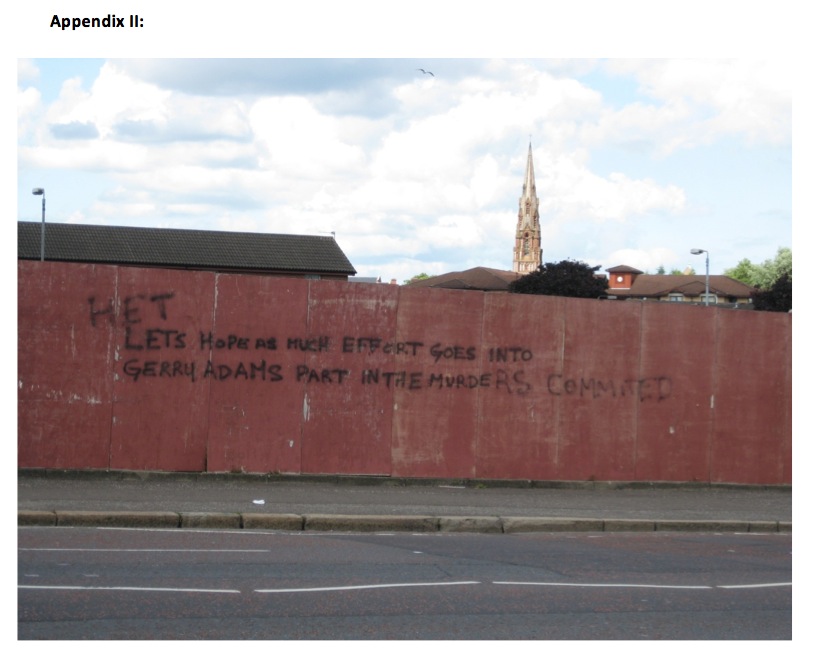

In Northern Ireland, there is certainly not a complete absence of violence. Cultural violence still exists to a degree, perhaps best embodied in the various paramilitary murals scattered around urban areas. Furthermore, those living in the poorest areas suffer from lack of housing, poor employment prospects and a shortage in affordable housing (Hall 2003). Consequently, these forms of violence become manifest through physical violence such as the events surrounding July 12th of this summer (BBC News,2010 [b][c]), while the fear of violence leads people to accept paramilitary policing (Cavanaugh 2000). Structural violence also becomes manifest through acts of crime and vandalism (see appendix II and V).

With regards to the organizations and their thoughts on peace in Northern Ireland, interestingly, when asked what peace in Northern Ireland looks like, the representatives of all three organizations answered differently. The first suggested that when the communities in West Belfast were ready to bring down the peacewall that separates them peace would be achieved, but made no suggestion of the communities mixing with one another (representative of Inter-Action, 22nd June 2010). The second had a more negative outlook and suggested the best we could hope for in the lifetime of this generation was for the absence of physical violence (representative of PRG, 24th June 2010). The last had much larger expectations of what needed to be achieved, talking of ‘fixing the cracks’ in society, and going much further beyond merely ending violence (Representative of the CRC, 25th June 2010). The dissonant nature of their responses suggest that there is little consensus over what is achievable in Northern Ireland. It also suggests that different areas are at different stages in the process of reconciliation, an idea explored in the next chapter.

Summary

Over the course of this chapter it should have become clear that despite Mendeloff (2004) claiming that consensus is emerging over the components of peacebuilding, there are still a myriad of approaches to take. No real consensus has formed over the best means of intervening in conflict, however, the majority of scholars emphasise a ‘multi-modal’ approach (Lederach 1997, Byrne 2001, Pearson 2001, Jeong 2005). We can conclude this section by saying that a very shallow form of peace exists in Northern Ireland. One article, as mentioned above, described the current situation as ‘no war, no peace’ (MacGinty et al. 2007). This is particularly true at the societal level where the people on both sides, of a predominantly working class background, suffer from continuing forms of structural violence which in turn breeds physical and cultural violence. Peacebuilding has taken a holistic approach in Northern Ireland, bringing together all sorts of local and international actors in a complex web of interaction. However, it will take a great deal of time to overcome the structural and behavioural dysfunction in Northern Ireland. Almost all focus is placed on the relationship between the Nationalist and Unionist communities to the detriment of the class dimension which is quite apparent in Northern Ireland.

Chapter 3: NGOs in Northern Ireland

3.1 The Evolution of NGOs and the Voluntary Sector in Northern Ireland

The roots of the NGO and voluntary sector in Northern Ireland can be traced back to the beginning of the troubles in the late 1960s. The experience of pre-1972 governance in Northern Ireland was very different for the Catholic and Protestant communities. While the latter regarded Stormont as their government (Cochrane and Dunn 2002: 52), the former felt little attachment to an institution they were either ideologically opposed to, or, disenfranchised from (Cochrane 2006: 256-257). A culture of self-help was, therefore, ingrained into the Catholic community resulting in the evolution of a vibrant and developed voluntary sector due to the politics of exclusion. The ensuing ‘Democratic deficit’ brought on by direct rule from Westminster between 1972 and 1998 instigated the evolution of parallel structures in the Protestant community (Morison 2006: 243).

The impotence and largely aloof nature of direct rule resulted in space opening up for the voluntary and community sectors to provide for their communities, while people interested in economic and social issues were attracted to these sectors due to the powerlessness of the political parties (Cochrane 2006: 256). These sectors were also highlighted as the best option able to deal with issues such as social exclusion which were outside of the reducing capabilities of the government, and unprofitable to the private sector (Morison 2006: 246). NGOs played a small but significant role during the peace process (1994-1998) by helping to rally support around the ‘YES’ campaign for the GFA, which perhaps would not have received such a strong mandate without their contribution (Cochrane 2000: 18).

The result today is a diverse and large NGO and voluntary sector in Northern Ireland. Around 5,000 organizations operate in a population of around 1.7 million people, with most facilitating community recovery through community development and conflict resolution projects aimed towards building social and economic infrastructure and promoting reconciliation between the communities (O’Brien 2007: 118). Previously, those playing the latter of these roles have been met with deep suspicion by both communities – perhaps due to their aversion to accepting government aid (Thiessen et al. 2010: 41). However, this issue was circumvented through the donations made by the EU and the American and Canadian governments to grassroots peacebuilding initiatives (Ibid. 42). The website of the Community Relations Council (CRC) in Northern Ireland lists 94 community relations organizations in operation (2010). According to Hancock (2008) this number reached 127 in 2007, indicating contraction in this sector.

3.2 Operation of NGOs

The substantial funding, discussed later, provided to civil society organizations shows the extent to which international donors put faith in the ‘third sector’ to push the peace process forward. The funds provided are expected to address economic deprivation, structural inequality, and improve relations between Northern Ireland’s divided communities (Thiessen et al. 2010: 42). While the majority of civil society organizations tend to provide a number of services, these are usually geared towards what they perceive as the source of instability between the Nationalists and Unionists. Cochrane divides the NGOs into two camps based on what they consider the main source of conflict in Northern Ireland (Cochrane 2000; Cochrane and Dunn 2002).

Tied to peacebuilding approaches, the first category places emphasis on the relationship between the communities and the creation of negative stereotypes belonging to the ‘behavioural approach’. These organizations therefore believe in fostering contact between the communities in a positive and controlled environment and engage in reconciliation and cross community strategies towards resolving the conflict and place emphasis on the ‘contact hypothesis’[8] and relationship building (Cochrane 2000: 14, Knox and Quirk 2000: 71).

The second of Cochrane’s groupings, the ‘structural approach’, places emphasis on a number of different variables that they perceive as being intransigent, and in this sense they subscribe to Arend Lijphart’s understanding of the static nature of culture and identity (Dixon 1997). These groups tend to focus on a mixture of the following: the sectarian division of the political system, socio-economic issues, the zero-sum game nature of the Protestant-Catholic relationship, the segregation of the communities, and the structures that have separated religion, education, music and sport (Cochrane 2000: 14). For this school of thought, any conflict resolution activity must address and manage the issues listed above which reinforce communal divisions and therefore cause conflict.

Within these two camps the NGOs in Northern Ireland operate in three strategic capacities vis-a-vis the communities. The first set engages in cross community activity. This is where organizations work with the Protestant and Catholic communities simultaneously on joint initiatives (Cochrane 2000: 8). The type of projects undertaken by these organization include problem solving workshops, dialogue groups, cross community forums, and other strategies geared towards underplaying religious and political differences while also fostering inter-group awareness (Hancock 2008: 219).

A second type of organization can be identified as inter-community, whereby they work with each community separately on the basis of their common socio-economic interests (Cochrane 2000: 8). Organizations that employ this approach tend to be involved in cross community work as well, but use this approach on more contentious matters or as a precursor to bringing the communities together to address the issue at hand.

The final category of NGO is the single identity groups that operate in only one of the communities. The idea behind this approach is to improve the livelihood of those living in the most deprived and insulated areas, as a preliminary step towards reducing sectarianism or tackling issues that affect both communities (Cochrane 2000: 8). The major controversy with these organizations, particularly when it comes to cultural traditions projects, is whether or not it merely creates ‘better educated bigots’ who have an even narrower and more exclusive understanding of their group’s identity (Knox and Quirk 2000: 79). A further question over their operation is when does the development of their own community end and the inter-community peacebuilding element begin? (Cochrane and Dunn 2002: 168-169).

Cochrane (2001) argues that the work done by single identity projects and groups tends to reinforce the groups’ identities. However, there are organizations that employ single identity projects who contradict this argument entirely. One need only look at the Peace and Reconciliation Group (PRG) in Derry/Londonderry who educate young Unionist men about Nationalist history and culture (PRG official website)[9].Moreover, not all groups have made the transition from community development to community relations, resulting in duplicitous groups and services in both communities which has led to funding being wasted (Knox and Quirk 2000). It is fair to say that single identity groups and most groups that include the use of conflict resolution techniques adopt a structural approach, while cross-community and reconciliation groups mostly use a behavioural model (Cochrane 2001: 107).

3.3 Typology of NGOs and Projects

The role of NGOs is varied with many NGOs continually adapting to the needs of their communities or reacting to specific events. Overall, the majority of organizations employ a number of different projects which tend to follow the typology listed below:

- Cultural tradition projects

- Community development/relations

- Reconciliation projects

- Reactive groups

- High profile community relations projects

- Education and personal development projects

(Hancock 2008: 219-220)

The basic typology above also provides a basic categorization for groups as well, in the cases where they were formed as a reaction to a single issue. Naturally, the context of the organization plays a large role in the type of people it attracts, and the kind of projects it uses to engage with the community it serves. For this reason, geographical location, local demographics and other variables must be taken into consideration when looking at the operation and composition of any organization (Cochrane and Dunn 2002). This means not only considering the number of Catholics and Protestants in the area, but also the levels of deprivation, education, and unemployment.

What these projects actually mean in practice will vary from organization to organization. In terms of peacebuilding and reconciliation, some organizations engage in confronting negative stereotype and perceptions by holding storytelling sessions, dialogue groups, and problem solving workshops (Thiessen et al. 2010: 42). Some engage with the local paramilitary organizations as a means of controlling violence (Inter-Action), while others work as advocates for ex-prisoners (Coiste, E.P.I.C), helping them to find employment and contribute to their local communities in some way. Another form of intervention is to train local community activists and leaders in the methods of conflict prevention and resolution (Peace and Reconciliation Group), in a bid to create non-violent community based conflict prevention mechanisms (Byrne et al. 2009). These forms of intervention would mainly fall under reconciliation projects, community relations projects and cultural traditions projects. However, these have been criticized as merely addressing the symptoms of the conflict rather than its root causes (Cochrane and Dunn 2002, Hughes and Donnelly 2004).

Another form of intervention is through community development. While all the projects listed above are about empowering people on the ground, these do so in a more tangible way. For example, these types of projects may help local people to obtain educational certificates, write CVs or funding applications, or even help to renovate local buildings (Byrne et al. 2009). These types of projects would fall under education and personal development, community development, and in some instances cultural traditions projects. In a number of cases, these will be of a single identity nature, meaning access to funding can be very limited. To circumvent this issue, a minimal community relations dimension will be tacked on to satisfy funders (Hall 2001). Discussion is ongoing over the sequencing of efforts to empower communities (Aiken 2010). Byrne et al. (2009: 56) found that community workers felt community development (structural) had to come as a precursor to peacebuilding (behavioural) work, while the view of the funders (the CRC) was the inverse (representative of the CRC, 24th June 2010).

On the whole, there is an unmistakable diversity of organizations and projects in place in Northern Ireland in terms of objectives and approach (Mulvihill and Ross 1999: 157). The very ambivalence surrounding the term ‘community relations’ has left it open to interpretation resulting in this plural approach (Hall 2001). In a number of cases, organizations will employ an array of these initiatives as they are seen as interdependent issues that must be tackled simultaneously in order to address community safety and need. Among the people running these projects there is recognition that only interventions that incorporate an effective development and peacebuilding approach will be successful (Byrne et al. 2009: 64). If this is indeed the case, organizations that incorporate both approaches into their conflict interventions are at an obvious advantage when engaging with the communities.

3.4 Attitudes towards the NGO Community and Community Relations

It has been mentioned above that those at the societal level can be very suspicious of government initiatives and their intentions. Any sign of compromise is regarded as giving in to the other community, in what is essentially a zero-sum game; engaging with the ‘Other’ is akin to betrayal (CRC 2009: 5). This is particularly true of the protestant community who have defined themselves on not giving ‘an inch’, while also viewing the peace process as being Republican centred (Southern 2007). For this reason, some practitioners argue that single identity work is necessary, particularly with the Protestant community (representative of the PRG, 24th June 2010). Attitudes towards the organizations and the work they do have a major impact on their potential to work effectively. So how do people view community relations work?

Initially, at least, the idea of cross community contact as a means of improving relations was criticized on three fronts. Firstly, it was seen by the Catholic community as a means of assimilating them to the culture of the Protestant majority (Hughes 2007: 24). Secondly, the Protestant community saw the concept as a political tool, and felt it was a waste of money that should have been used to counter the threat of the IRA (Hughes and Donnelly 2004), while also believing it to be an attempt to dilute their culture (Knox and Quirk 2000). Finally, working class communities from both sides regarded the attempts of community relations as tackling the symptoms of the conflict (lack of cross community contact) rather than addressing the roots of the conflict (deprivation and structural inequalities) (Hughes and Donnelly 2004: 572), a criticism also levied against the organizations by academics (for example Cochrane and Dunn 2002).

While community relations is promoted by those at the top of the pyramid as the best means of moving out of the conflict, it has yet to be given the same priority by local political initiatives (CRC 2009: 2). It is argued that those on the ground have little concern for the opposing community when they are suffering from alienation, deprivation and violence (Hall 2001: 7). Cochrane (2001, 2002) adds to this by suggesting that high profile reactive groups such as ‘Peace People’ and ‘Peace Train’, seen as mainly being comprised of ‘middle class do-gooders’, detract from the NGO community as a whole. Furthermore, there is scepticism shown toward those who are known to receive community relations funding (Hall 2001: 17). This scepticism is partially due to the worries over the intentions of those providing the funding and the fear and distrust of the other side, but also because of some of the projects that have received community relations funding[10].

Even the thought of engaging with the other side represents a massive psychological step for many in Northern Ireland (representative of Inter-Action, 22nd June 2010). There has been a great deal of discussion over the concept of growing ‘Protestant alienation’ which has left certain parts of the Protestant community in fear and isolation (Southern 2007).This is particularly true of the working class Protestant community who equate engaging in community relations work with the first step towards a united Ireland (representative of the PRG, 24th June 2010). This can be combined with research conducted by Hughes and Donnelly (2004) which showed that overall Protestants are less willing to engage in community relations work than Catholics[11] .

While both communities have, for the most part, come round to the idea of such work being done there remains an element of danger posed to those who try to engage in cross community work. Some, like the PRG are treated with suspicion by paramilitaries and, in their case, the British army (Mulvihill and Ross 1999: 151). Others, like Inter-Action have received death threats for their attempts to mediate between local stakeholders (representative of Inter-Action, 22nd June 2010) Mary Kelly, a prominent community worker in North Belfast has been attacked on three separate occasions this year for the work she has done working between the Catholic and Protestant communities on the Glandore/Skegoneill interface (Belfast Telegraph 2010, Evening Herald 2010). Indeed, events at the micro-level can be held hostage to those that occur at higher levels. Research has shown that attitudes towards ‘the other’ and confidence within communities is often related to the ‘headline grabbing events of the day’ (Hughes and Donnelly 2004: 587). This, inevitably, leaves the work of organizations in local communities exposed to events elsewhere.

3.5 Funding: The Community Relations Council (CRC)

Economic aid is a crucial part of peacebuilding initiatives in Northern Ireland (Byrne et al. 2007: 8). Northern Ireland has enjoyed ‘unprecedented’ access to funds for reconciliation and peacebuilding projects (Aiken 2010). Through international funding, projects aimed at peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland have had access to sustained funding. Initially, the European Union (EU) contributed with Peace I (1995-1999) committing €667 million ‘to reinforce progress towards a peaceful and stable society and to promote reconciliation by increasing economic development and employment, promoting urban and rural regeneration, developing cross-border co-operation and extending social inclusion’ (EU 2007: 4). The perceived success of Peace I brought further contribution to Northern Ireland and the border region with the extension of the programme into Peace II (2000-2004), and the resulting allocation of €995 million. This was extended by two years with an additional €160 million granted. The current phase of the programme is known as Peace III (2007-2013), with a further contribution of €225 million to be made. This final figure represents a much smaller number than in previous years, representing just under 20% of the overall Peace II figure.

The CRC is the primary intermediary organization for groups seeking funding for projects, or core funding[12], with an exclusively ‘community relations’ focus. Other bodies exist for projects of other types, for example, the International Fund for Ireland (IFI), which has contributed £628 million to 5,800 projects across Ireland (IFI official website), and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which makes charitable donations to projects seeking to alleviate poverty in deprived areas (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, official website). For those working to bring the communities together on projects, in a cross or inter community capacity, this is the most important organization. The idea behind the creation of the CRC was to form a new community relations agency to act as a ‘focal point’ encouraging cooperation and the sharing of good practices as well as advice, training and liaison services for the community relations sector (Hancock 2008: 221).

While not a regulatory authority, the CRC does act as a gatekeeper to funding and as an umbrella organization for the NGOs in Northern Ireland. NGOs are evaluated to ensure the work they are receiving funds for is actually being done. Regular meetings are held with organizations that are funded by the CRC, while individuals whose salaries are paid for by CRC core funding must provide reports on the work being done which are evaluated by the CRC (representative of the CRC 24th June 2010). Although the organizations funded have the ability to impact at the community level, the CRC operates strategically to coordinate the actions of this myriad set of groups to create an impact at the national level.

However, those interviewed by Byrne et al. (2007: 16) pointed to the fact that these regular reports created a great deal of bureaucracy for smaller organizations and essentially trapped them into a funding cycle:

“When that money generates an employee, the paid employee is so tied up in actually dealing with the bureaucracy that the immediate thing for them is to secure more money to employ another employee to do what they were supposed to do. That is cascaded down the line.”

This also means that smaller groups are left at a disadvantage as they lack the resources to secure funding in the first place. Bureaucracy, therefore, has disenfranchised a number of smaller groups, and, with those most in need of funding coming from poorly educated working class backgrounds, many people cannot navigate through the funding application forms (Byrne et al. 2009: 51).

As a rule, the CRC will not fund single identity work. Although, if it is clear that the single identity project will be followed up by a cross-community dimension, some preliminary funding could be made available (representative of the CRC 25th of June 2010). However, as mentioned above, criticism has been levied against funding bodies for some of the projects that have received money, while in some cases projects have added a community relations element to placate funders (Hall 2001). Moreover, it has been suggested that in some cases, though not in the CRCs, funding and evaluating bodies are not sensitive to those on the ground, and do not value psychological and reconciliation work that are not unquantifiable, but make up a large part of the peacebuilding reconciliation processes (Hall 2001, Byrne et al. 2009). Instead, it has been argued that funders prefer ‘bricks and mortar’ projects that provide tangible evidence of change (Last 2000). Research by Byrne et al. (2007) found this to be the case in Northern Ireland, particularly in the case of the IFI.

Finally, there is concern over the fact that criteria states that, in the majority of cases, there must be a mix of Catholic and Protestants in any projects that need funding (Hall 2001, Byrne et al. 2007, Byrne et al. 2009). This forces reconciliation processes that have to happen naturally (Hamber and Kelly: 9). Funds and time are, therefore, wasted on projects that cannot operate effectively because the people involved are not prepared to commit to the project. In other cases, this results in a minimal community relations dimension being added on to a project merely to satisfy funding criteria (Hall 2001, Byrne et al. 2009)

As funding becomes tighter, less and less money will be available to share amongst the various NGOs. Therefore, those at the baseline of funding priorities will be the first to suffer, while those higher up will be forced to make joint bids or cut down on the scale of their activities. Future financial austerity in the British government and EU will undoubtedly have a major impact on the community and voluntary sector in Northern Ireland. The source of funding has led some to argue that these are not in fact NGOs at all, claiming that they are not free of the influence of government (Knox and Quirk 2000). The CRC accepts that the days of substantial external funding are coming to a close (CRC 2009). This may see a reverse in what Cochrane (2006: 258) has called the ‘professionalization’ of the voluntary and community sector, a large reduction in the number of organizations operating, or NGOs scaling back the number of projects and their activities. This has already begun with the number of organizations dropping from 127 in 2007 to 94 in 2010.

Summary

There is a large and vibrant NGO sector in Northern Ireland that provides a diverse range of services to local people. There are a number of approaches to intervening in the conflict whether it is through working with the communities together, separately and simultaneously, or by trying to build the capacity of one side alone. The kinds of projects employed depend largely on what the organization sees as the roots of the conflict and there a number of methods of addressing these issues. However, attitudes towards some of the work being done provides an obstacle to the operation of these groups, while the success of an organization in engaging with the local people can also rely on who they have representing them. Finally, past funding has been extremely generous. However, with highly reduced European funding and inevitable cutbacks from the British government, organizations are going to find that the days of employing several projects and employing a team of employees are over.

Chapter 4 Case Study: Inter-Action Belfast

4.1 A Brief Introduction to the Organization

Born out of frustration at the impotence of existing efforts at community relations in one of the areas most affected by the troubles, the Springfield Inter-Community Development Programme (SICDP) was formed in 1988 by two active members of the Catholic and Protestant communities. The activists sought to adopt a community development approach within both communities while, more importantly, addressing the conflict between them (Inter-Action: Official Website).In previous work friendships had been established through ‘ghettoway days’ and children’s’ holidays, however people often reverted back to their old mindsets when they returned to their segregated communities (Cochrane and Dunn 2002: 93, Inter-Action: History). As employers left the area and tensions increased along the interface, there was a growing realisation that a radically new approach was needed to community relations work. In the spring of 1990 funding was secured to employ a project director. Billy Hutchison, a Loyalist ex-prisoner was appointed to the position with Pat McGeown, a prominent Republican ex-prisoner, selected as a high level member of the management committee (Inter-Action: History). In 1992, Tommy Gorman, another Republican ex-prisoner, was given the role of community development worker for the Nationalist side of the interface, and both men set about encouraging the community groups to engage with one another. From the beginning, the project has involved ex-prisoners, capturing the very ethos of the organization that all stakeholders in a conflict should be involved in its resolution (Inter-Action: Ethos).

The first major public event of the SICDP came in October 1992 with a local conference being held called: ‘life on the interface’. This conference covered a number of issues facing the interface community and was attended by members of 60 different community organizations along the interface (Inter-Action: SIF). The report from this conference became the first of the Island Pamphlet Series, some of which have been used as part of this research. This was later re-launched as the Farset Community Think Tanks Project in order to provide a format for all members of the community to articulate and debate important issues affecting their lives (Inter-Action: History). The pamphlets have been spread to organizations throughout Northern Ireland in an attempt to encourage similar debates and share information of best practices, successes and failures with other communities. The SICDP was one of ten organizations chosen for study by Cochrane and Dunn (2002), as well as by Connie O’Brien (2007). Cochrane and Dunn described the SICDP as ‘inter-community’, however the organization has evolved to the point where it employs all three approaches to community relations/development simultaneously. The SICDP was renamed Inter-Action in 2002.

4.2 Context: The Area and the People

Inter-Action’s office is situated in the Farset Enterprise Park which lies just off the main interface along the Springfield road. The interface area that the organization deals with stretches for over two miles and represents the longest interface in Northern Ireland (Inter Action: SIF). This particular interface resides in west Belfast and in its remit includes two of the most notorious areas in Belfast and Northern Ireland: The Springfield /Falls roads on the Nationalist side, and the Shankill road on the Unionist side. The Springfield/Falls/Shankill interface represents one of the most volatile trouble spots in Northern Ireland’s history. Furthermore, the 12 government wards that fall under the Inter-Action remit have been highlighted as areas of chronic need and deprivation (NINIS: Official Website). The existence of the ‘Peacewall’[13] perhaps best exemplifies the complicated and potentially volatile nature of the relationship between the two communities in the west Belfast area.

The ethos of Inter-Action is based on the inclusion of all local stakeholders playing a role in the building of relationships based on confidence and trust (Inter-Action 2006: 27). This includes, in some capacity or another, ex-combatants and current members of paramilitary groups. The role of ex-combatants is a particularly important aspect of the work done by the organization, a fact recognised by the publishing of ‘The Role of Ex-Combatants on Interfaces’ (2006) which provides a comprehensive profile of the role currently played by ex-combatants who have chosen to engage in community relations/development work. The research that this report was based on by Shirlow et al. (2006: 76), argued that precisely because of the ‘extreme’ backgrounds of ex-prisoners they had the credibility to demonstrate leadership within and between communities that were the most affected by the conflict.

Furthermore, engagement with both sides and both sets of ex-combatants illustrates the importance the organization places on not blaming either side for the conflict and instead engaging with all those affected in a positive way. This, inevitably, includes the paramilitary groups in order to provide analysis and models of non-violent action to resolve conflict across the interface (Inter-Action: Projects/Community Networks). Working with the paramilitary organizations is key to ensuring violence is kept to a minimum in the areas they operate. This has, however, resulted in members of staff receiving death threats, resulting in an element of danger in the work done (representative of Inter-Action, 22nd June 2010).

The organization has been keen to stress its inclusion of both communities in its activities and membership. While being involved with ex-combatants since the project’s inception, the current Board of Directors has always been composed of four active members of each community[14]. Current board members are: Lorraine Butler, Cilla Fleming, Tommy Holland, Harry Maguire, William McQuiston, Mary McKenna, Sean Murray, and Tom Roberts. Furthermore, the people who work within the organization, and with the communities, are based in the communities themselves, with both community development officers living on either side of the wall. This, of course, allows for close contact with the local community and less suspicion of their motives. The staff of Inter-Action are:

- Roisin McGlone – Chief Executive Officer

- Terry McKeown – Finance/Administration

- Rita Geraghty – Cross Border Development Worker

- Julieanne McCarthy – Cross Border Finance/Administration

- Noel Large – Interface Development Worker

- Daniel Jack – Interface Development Worker

Moreover, the community activists associated with the organization, ex-combatants or otherwise, tend to be held in high esteem by their communities, offering a certain amount of influence over the local people. For example, Noel Large, an interface development worker with Inter-Action, is a Loyalist ex-prisoner and works on the unionist side of the interface. Drawing on local resources and offering expert knowledge of local people and culture is, therefore, critical to how Inter-Action operates. Having to employ two finance/administration staff adds credence to the claims of Byrne et al.’s research (2007, 2009) which found that accepting funding tied groups into dependency and overstaffing in order to deal with the paperwork involved with accessing funds.

4.3 How do they Serve the Communities? Projects and Activities

The Mobile Phone Network (MPN) was set up in 1998 by the SICDP as a means of tackling sectarian incidents along the interface. Rumour and a lack of communication between the communities had previously been singled out as two of the main causes of violence. With no communication between the communities, rumours spread on either side of the wall about small incidents which would eventually trigger violent reactions to events such as football fans singing in the streets or stones being thrown over the wall (representative of Inter-Action, 22nd June 2010). Events like this were underlined as a key source of conflict along the interface:

‘…shared suspicion and misunderstanding which had gripped both communities in Northern Ireland and helped ensure that the growing inter-communal violence would intensify.’ (Hall 2003: 3)

The physical barrier between the communities, coupled with the psychological barriers in the form of prejudice, suspicion and fear, combined to allow small events to escalate into full blown riots in the past. The Mobile Phone Network was designed to tackle such issues before they had the chance to erupt into full scale conflict involving dozens of members of each community. 28 mobile phones were distributed to a diverse group of voluntary community activists (Inter-Action: Projects/Community Networks). Each member is also given a geographical area of responsibility so that when incidents of stone throwing or other forms of vandalism occur phone holders may contact one another over the interface to de-escalate any potentially volatile situations that may arise. The project helps to: calm people, defuse tension, promote local resolution of issues, reduce and prevent interface violence and facilitate communication (Inter-Action: SIF).

The Springfield Inter-Community Forum (SIF) was a natural product of the mobile phone network, with users beginning to meet formally to discuss issues that had arisen from 2001 onwards. The forum consists of 30 community activists from organizations along the interface who have a commitment to building bridges across the wall and improving the quality of life for those on both sides of the interface (Inter-Action: Projects/Community Networks). While there was clearly tension to begin with, groups had to be kept in separate rooms while discussions took place, eventually members of both sides of the community were able to sit in the same room and discuss the needs and concerns of community openly and honestly (Inter-Action: SIF). Acts of cooperation in one area, therefore, built enough trust to approach new areas of cooperation. A wide range of representatives of organizations are brought together including members of PSNI, NIO, Irish government, members of political parties, ex-prisoners groups, Belfast City Council, and Social Services (Inter-Action: Projects/Community Networks). The Forum is used as a means of identifying community need, and once that need is identified Inter-Action formulate a project that will address this area. The SIF is, therefore, at the centre of everything that Inter-Action does; all other projects feed into or out of this project to some degree or another (representative of Inter-Action, 22nd June 2010).

Another project with the aim of building trust at the local level is Policing in Partnership. The idea behind this project was to build trust between the PSNI and the local nationalist and loyalist activists. This was done by delivering workshops separately to members of the PSNI, senior republican activists, members of Sinn Fein, Loyalists activists and members of the PUP and UPRG (Inter-Action: History). At first this was a very delicate process and had to be done confidentially. This project has allowed the police to operate in a more effective capacity in the communities, while previously they had struggled to engage with either side, particularly the nationalists[15]. Building relationships on this front was seen as important, not only for community safety, but also in educating the police on how to effectively and sensitively provide their service to both sides of the local community.

More generally, the interface development workers engage with the local communities on a daily basis. The interface development workers identify the needs of individuals and groups and seek to address them through Inter-Action. For example if stones are constantly hitting a family’s window causing constant damage, the development workers help the residents to acquire a steel cage for the garden or Perspex windows to prevent the damage. Similarly, there have been a number of cases where building contractors are employed by the government to build housing in the local area. However, none of the local workforce has been used, and the housing has been too expensive for local people to rent or buy causing anger in the local communities (see appendix IV). Inter-Action have stepped in to ensure that builders ‘give something back’ to the local community whether by providing jobs to local people during construction, or ensuring the housing is suitable for local residents (representative of Inter-Action, 22nd June 2010).

Finally, Inter-Action is engaged with other local organizations and individuals which are also attempting to run projects or help their communities in some way. Inter-Action provide advice for other organizations wishing to access funds for projects, as accessing this money can be a complicated process with some funding applications requiring a 40 page application plus appendices (representative of Inter-Action, 22nd June 2010). It has been mentioned before that small organizations are put at a disadvantage by the application procedure (Byrne et al. 2007). Inter-Action, therefore, seeks to empower local organizations by helping them to negotiate this difficult process and access funding to help the local community. Moreover, Inter-Action will also help by managing the financial matters of smaller organizations in their remit as well as facilitating meetings for other community relations groups on their premises.