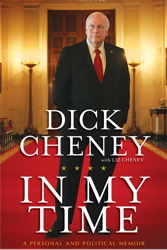

Despite a high-profile, often turbulent political career spanning four decades, Dick Cheney’s memoir In My Time is a disappointment to anybody hoping for some illumination on one of the most controversial U.S. administrations in recent history. Unlike most previous holders of the vice presidency, Cheney was an activist under George W. Bush, notoriously forthright with his opinions, deeply conservative, and a strong advocate of an aggressive foreign policy. During his tenure he was involved in several decisions that have defined the early twenty-first century.

Despite a high-profile, often turbulent political career spanning four decades, Dick Cheney’s memoir In My Time is a disappointment to anybody hoping for some illumination on one of the most controversial U.S. administrations in recent history. Unlike most previous holders of the vice presidency, Cheney was an activist under George W. Bush, notoriously forthright with his opinions, deeply conservative, and a strong advocate of an aggressive foreign policy. During his tenure he was involved in several decisions that have defined the early twenty-first century.

Delivered in a strict chronological narrative, what is most remarkable about the first four chapters on the obligatory family history and early career, is a sense of why Cheney was motivated to serve in public office. Acquiring his first taste of politics as an intern in the Wyoming state legislature in 1964, he became the youngest White House Chief of Staff in history under President Ford, at 34. After Ford lost the 1976 presidential election to Jimmy Carter, Cheney decided that what he “really wanted to do was run for office” (p110). Run he did, becoming a 6-term member of the House of Representatives, but his motivation seemed born more out of disinterest with the career alternatives of academia or business than serving the people of Wyoming. Similarly, we are left in the dark as to his motivations for countenancing a presidential run in 1998 other than because he “knew what it takes to make an effective chief executive” (p242). Cheney is not a man easily given to introspection.

We are, however, given an interesting insight into his time as Chief of Staff under Ford, a man whom he considered “as worthy of that office as any who ever come before” (p108). He is humble enough to concede that Ford’s surprise pardon of President Nixon, a decision Cheney and many others at the time considered a mistake, would in hindsight be recognised for its “courage” and “rightness” (p69). Ford was commonly portrayed as a clueless bumbler, cruelly ridiculed on shows such as Saturday Night Live, but after the rancour and divisiveness of Nixon’s aborted second term, Cheney is keen to stress the “warmth and camaraderie” of the Ford administration began with the good spirit of their leader (p109).

Much of the book, seven of sixteen chapters, is given over to discussing the Gulf Wars and Afghanistan (during which time he served as Secretary of Defense, 1989-1993, and Vice-President, 2001-2009). Despite the huge economic and human cost of the second Iraq War, never finding weapons of mass destruction, and the fragile gains on the ground that now appear to be unravelling, Cheney remains resolute that the country’s liberation was “one of the most significant accomplishments of George Bush’s presidency.” And in typically bullish fashion he refuses to acknowledge America’s role in facilitating and provoking the post-invasion escalation in violence; responsibility for that lies with the terrorists, he counters, and those supporting them, namely al Qaeda and Iran (p434).

He is equally defensive (and at length, pp348-363) of his position on enhanced interrogation techniques and opening Guantanamo Bay, both essential tools, he maintains, in prosecuting the War on Terror (capitalised throughout the book). He point outs, for example, that it was information obtained under these methods from one of Osama Bin Laden’s lieutenants, Abu Zubaydah, that identified Khalid Sheik Mohammed as the ringmaster behind the 9/11 attacks (pp357-8). The program also yielded information that contributed to the location and killing of Bin Laden in May 2011. A “new kind of enemy”, argues Cheney (despite being the same enemy that attacked the World Trade Center in 1993, the U.S. embassies in East Africa in 1998, and the U.S.S. Cole in 2000), demanded new measures that could help secure the nation. The ends, Cheney implies, largely justify the means.

Much like other notable memoirs from the Bush administration there is nothing particularly revelatory in Cheney’s account other than perhaps his candid disappointment with some of Bush’s decisions – his refusal to pardon Scooter Libby, for example, was a “grave error”, akin to “leaving a good man wounded on the field of battle.” (p410) His tensions with Secretary of State Colin Powell and his successor Condoleeza Rice were well known and have not diluted with the passage of time, and neither have his conservative credentials or hawkish position on foreign policy. The 527 pages are easy enough to move through if somewhat dull for extended periods, but those hoping for a greater insight into this divisive period in recent American history will be left unfulfilled.

Chris McCarthy is a member of the e-IR editorial team. He is currently at KCL’s War Studies Department, holds an MSc in International Public Policy from UCL and a BA in History from Durham University.