I. INTRODUCTION

Just over one century ago, British diplomat and scholar Herbert Samuel did not consider immigration a topic worthy of analysis (Samuel 1905: 332). Today, no serious social analyst could possibly dismiss the impact of immigration so flippantly. Indeed, in 2010, more people lived outside their birth country ‘than in any other period of human history’; an estimated 200 million people can now properly be defined as migrants (Esses et al. 2010: 635). Rather than considering the effect of cans of hot water dumped into the sea, a more appropriate comparison might be one with climate change – a process whose effects are contested, but whose existence is undeniable, and transformative. In the modern era, immigrant flows are principally from less-developed to highly-developed nations; as such, immigration has become a controversial issue in many western nations, intersecting as it does with ‘security, terrorism, and globalization’. (Breunig and Luedtke 2008: 123). Immigration is a quintessential multi-dimensional issue, impacting virtually every dimension of domestic and foreign affairs.

In recent years, increasing immigrant flows to highly-developed nations have led to calls for restrictive numerical caps, and also to the rise of several ‘openly xenophobic right-wing political parties’, particularly in Europe (Ceobanu and Escandell 2010: 310). Indeed, recent surveys find that a ‘general trend’ of anti-immigration attitudes is prevalent in the western world, many of whose citizens view immigrant influxes as threatening, despite the often ‘huge’ economic benefits which accompany them (Breunig and Luedtke 2008: 123).

To explain this apparent paradox, a niche field of research has burgeoned, seeking to access and explain determinants of opinion on immigration. This is a relatively new field, but a key consideration that emerged early was the ‘relative salience of…economic versus cultural’ vectors of opinions in determining top-level attitudes toward immigration (Brader et al. 2008: 961). The importance of this distinction cannot be underestimated; markedly different policy responses are required to improve social cohesion depending on whether opinions are predicated more on economic or cultural foundations.

In an effort to explore this crucial distinction, a case study approach was devised, comparing Canada and France. While both affluent western nations with long histories of planned immigration, they diverge wildly with regard to how immigration is perceived. Furthermore, Canada is a country wherein studies have argued for the predominance of economic factors in explaining positivity, whereas studies in France have highlighted the primacy of cultural factors. As such, they make for an ideal comparative analysis; further details are supplied in the section on ‘Case Selection’. Too often, claims have been made about the importance of cultural or economic factors without sufficient backing. In this study, surveys were devised to measure economic and cultural attitudes toward immigration, and statistical analysis performed to determine which were more significant. Results were unclear in the Canadian context, with cultural and economic opinions appearing to be equally related to top-level opinion; in France, cultural opinions had a stronger effect.

The major contribution of this study is to internationalize the study of exogenous attitudinal determinants to immigration. Some studies emphasize the importance of economic reasons in determining such attitudes, while other studies stress cultural factors. Studies in the literature have compared these dimensions within but not across nations. Indeed, there is ‘surprisingly little comparative work’ on immigration topics in general (Rayside 2011: 1). As such, this study represents a small but innovative step down a new avenue of research. Are certain factors most important in some nations while others predominate elsewhere? Why this should be the case represents still another rich vein of inquiry. Context clearly matters, but to what extent? Further research is needed in this field. As immigration becomes increasingly important in the western world, understanding the relative importance of economic and cultural opinions can help to shape policies leading to social cohesion, rather than turmoil.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

Case Selection

Canada and France make for an excellent comparison in assessing the relative strength of economic and cultural factors in determining opinions about immigration. Both countries are ‘modern, western… individualistic societies’ with high levels of affluence and quality of life. Both also share a long history of large-scale immigration (Berry and Sabatier 2010: 192). However, 67% of Canadians see immigration in a positive light, whereas 59% of French respondents hold neutral or opposite views. Canada perennially scores highest among western nations in terms of positivity about immigration, while France’s results are typically found at the opposite end of the spectrum. (Simon and Sikich 2007: 961). Furthermore, Canada is a country wherein studies have argued for the predominance of economic factors in explaining positivity, whereas studies in France have highlighted the primacy of cultural factors in explaining negativity (Facchini and Mayda 2008, Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007). As such, the two make for an excellent comparative dyad.

Canada as an Outlier

Canada is a clear outlier in the domain of immigration politics, both in the sheer numbers received, and in the overwhelming positivity of citizens to demographically expansionary policies. Even in the nineteenth century, commentators noted the welcoming nature of the land and its people. In 1895, British MP Geoffrey Drage noted that Canadians were ‘more favourable to the adoption of measures for inducing immigration’ than any other people (Drage 1895: 26). Not much has changed; since the end of the Second World War, the country has admitted the highest number of immigrants per capita of any country in the world (Fortin and Loewen 2004: 2). Remarkably, this unprecedented flow has not caused significant ill-will among the native-born population; indeed, Canadians also lead the world in ‘support for immigration…by a wide margin’ (Hiebert 2006: 41). Canada is a clear outlier in its positivity on immigration; its citizens are ‘least likely of any country’ to claim there are ‘too many’ immigrants in the country, and most likely to call immigration an opportunity rather than a problem (Gustin and Ziebarth 2010: 980). As if that weren’t striking enough, Canadians are also more likely than any other western people to support increasing levels of immigration above and beyond their world-leading levels; nearly one-third of those surveyed in 2006 expressed unqualified support for this proposition (Jedwab 2006: 8). From the earliest days of Canada’s nationhood through the twenty-first century, Canadian attitudes towards immigration have been characterized by a positivity and receptiveness extremely uncommon in the western world. Which factors explain this rare attitudinal orientation?

Economic Attitude Determination in Canada

Canada includes…means for the employment of capital and labour…in an endless variety (Dufferin 1874: 3).

It has been by…flow of population from other lands that the development of Canada to its present status has been achieved (Stead 1923: 56).

Although much has been written on Canada’s status as a settler society, and its innovative official policy of multiculturalism, most scholars attribute Canada’s positivity on immigration primarily to economic factors. It has been theorized that English-speaking ‘settler societies’ have a uniquely welcoming predisposition towards immigration, given that they are basically nations of immigrants. According to settler society theory, such nations should generally favour ‘expansionary policies’, and their people should espouse similarly receptive opinions (Freeman 1995: 881). This theory alone, however, fails to explain the significant opinion variance among settler societies. Some have suggested that Canada’s 1971 constitutional Policy of Multiculturalism helped shape a normative socio-political culture which is uniquely receptive to immigration (Berry 2006, Hochschild and Cropper 2010). Most theorists, however, point firmly to economic explanatory factors. Canada admits migrants according to a points-based system predicated on ‘labour markets and national priorities’; as a result, immigrants are matched to industries – and geographic regions – where their skills are most in demand. Consequently, immigrants are seen as valuable contributors to the economy, and tend to have high rates of employment (Gustin and Ziebarth 2010: 980). Nearly forty percent of immigrants to Canada are admitted on skills-based criteria, as opposed to family reunification or humanitarian purposes. To put this figure in perspective, fewer than ten percent of immigrants to the United States are admitted on skills-based criteria. It is theorized that the Canadian approach not only works on economic grounds, but also mitigates cultural friction by attracting a broad ‘national-origin mix’ of immigrants (Antecol et al. 2003: 197). Most scholars now support this ‘cultural-harmony-through-economic-success’ narrative in the Canadian context. Several studies have concluded that while cultural factors may matter in explaining Canadian positivity to immigration, political economy factors are unquestionably predominant (Thompson and Weinfeld 1995, Entorf and Minoiu 2005, Hiebert 2006, Facchini and Mayda 2008, Wilkes et al. 2008). Shaped by strategic economic migration policy, (culturally diverse) immigrant flows fill gaps in Canadian labour markets, contributing to full employment, general economic health, and consequently positive views of immigration – so runs the dominant argument in the literature.

France as an Outlier

In stark contrast to Canada’s positivity, French citizens tend to be much more suspicious of immigration, and their attitudinal vectors trend towards limitation and even exclusion. In a 2003 cross-national study of western nations, fully sixty-six percent of French respondents expressed support for a reduction in immigration to France (compare this figure with a mere thirty-two percent in Canada); this figure led all nations with the exception of the United Kingdom (Simon and Sikich 2007: 957). Where two-thirds of the population express discomfort with immigration levels, a clear problem exists. Further, French citizens are more likely to report ‘too many’ immigrants in their nation (German Marshall Fund 2010a: 6). Indeed, the antipathy towards immigration is such that some scholars consider France a ‘model of how not to handle immigration’ (Hochschild and Cropper 2010: 21). In the 1970s, French attitudes toward immigration were described as ‘nativist, or anti-foreign’; in the 1990s, they were characterized as ‘highly volatile and conflictual’ (Palmer 1976: 488, Freeman 1995: 881). Plus ça change: the situation does not appear to have changed significantly. Indeed, although France has had over a century of planned immigration, the national identity seems ‘devoid’ of a narrative that is positive about it (Hein 1997: 1751). France, like Canada, is an outlier in terms of opinion on immigration – but in the opposite direction. Similarly, the explanations for this phenomenon are distinctly divergent.

Cultural Attitude Determination in France

France as a whole… exhibits many of the evil effects of immigration (Drage 1895: 11).

It is normal, and it is sane, that a group not let itself be penetrated from the exterior without control (Girard 1977: 227).

In another stark contrast with Canada, analysts of the French immigration context attribute negativity primarily to cultural, rather than economic factors. France’s ‘model of assimilation’ is fundamentally at odds with Canada’s; rather than encourage the adoption of multiple, layered identities, French republicanism promotes the absolute superiority of traditionally ‘French’ culture (Martin 1994: 165). Also termed ‘assimilationist citizenship’, this approach sees particularized ‘cultural rights’ as ‘an obstacle’ to a united France (Berry and Sabatier 2010: 192). Rooted in a well-intentioned desire to establish liberty, equality, and fraternity for all, this model involves a necessary ‘allegiance to customary institutions and practices’ (Blake 2003: 492). However, many have argued that this strain of republicanism has constructed a ‘negative folklore’ surrounding immigration; new arrivals not conforming to traditionally French values, norms, and cultural behaviours are viewed as subversive, destabilizing, or even dangerous (Freeman 1995: 884, Blake 2003, Furlong 2010). As such, in the French context, studies have found that opinions on immigration are ‘surprisingly unrelated’ to economic factors (Citrin and Sides 2008: 33). Indeed, French attitudes about immigration have been shown to ‘have very little, if anything to do’ with labour market realities; in short, the political-economy argument holds very little weight in the French context (Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007: 399). Similar findings have been made by several survey studies over the past half-decade (e.g. Fassin 2005, Green 2009). Shaped by a prescriptive model of republican assimilation, the French are more likely to perceive cultural differences as threatening, and thus express lower levels of support for immigration in general. The literature holds that attitudinal determinants are primarily cultural in the French context, and are, indeed, ‘surprisingly’ unrelated to economic variables.

III. RESEARCH QUESTION & HYPOTHESES

What explains variance in terms of public opinion on immigration? This is our major category of interest, which leads us to our research question, and hypotheses.

RQ: In Canada and France, is general support for immigration more strongly related to cultural or economic opinions?

This study is concerned primarily with testing dominant hypotheses in the literature about the strength of economic versus cultural determinants of attitudes on immigration. Four dominant hypotheses were tested by survey research; these flow logically from the findings made in the literature review, and are outlined below:

H1: Canadians have generally positive views of immigration.

H2: The French have generally negative views of immigration.

H3: Canadian attitudes about immigration are predominantly based on economic factors.

H4: French attitudes about immigration are predominantly based on cultural factors.

Hypotheses one and two are based on a significant body of survey research; results are expected to support these suppositions. If H3 is confirmed, this will strengthen the assertion that attitudes in Canada flow from economic realities (likely policy prescriptions and consequences); if invalidated, we can infer that insufficient attention has been given in the literature to the extent to which immigration attitudes are shaped by cultural factors. If H4 is confirmed, this will validate the claim that ideational identity factors are paramount in the French context; if invalidated, we can infer that resource competition is likely a more important determinant than has been theorized.

IV. METHODOLOGY

In order to test the hypotheses, a survey project was designed to gauge both general attitudes to immigration, and their constituent components. Guided by the literature on attitudinal determination, questions were aimed at accessing opinions regarding both the cultural and economic aspects of immigration. The majority of the survey is composed of Likert-scaled questions, wherein respondents must determine their own position on ‘an attitude continuum’ (Oppenheim 1992: 195). Only six of the twenty-two substantive questions are categorical (wherein respondents must choose from a non-continuum set) rather than Likert or rating-scaled. Three versions of the survey were designed: one each in English and French for Canada, and one in French for France. Questions citing factual data were changed depending on the nation concerned, and translation was carried out by a professional French translator. Copies of the survey instruments employed are included in Appendices 2-4. This survey project was registered with University College London’s Data Protection Administrator, who authorized the research as ‘Social Research No Z6364106/2011/07/33, section 19’.

The survey instruments were tested by fifteen respondents in both Canada and France; the process led to some important rewordings and clarifications. Experts claim that most ‘major difficulties and weaknesses’ in survey design can be identified by testing fewer than twenty respondents (Presser et al. 2004: 110). The process has been called a research ‘dress-rehearsal’, and its ‘earliest references’ in academic writing date from 1940 (Presser et al. 2004: 109). Pretesting surveys involves iterated reviews of the instrument with potential respondents, in an effort to improve questionnaire design through the elimination of ambiguous or confusing questions. The process of pretesting resulted in some question re-ordering and rewording within the present study.

The population frame for the survey was composed of Canadian and French residents, aged sixteen and up. The deliberate exclusion of people under sixteen is defensible in the name of ‘politically important sampling’, a process whereby respondents whose opinions are not electorally-relevant now, or in the very near future, are excluded (Onwuegbuzie and Leech 2007: 113). In one landmark study of one thousand respondents aged nine through fifteen, it was found that children’s opinions remained consistent only on ‘obvious’ questions regarding sex and school grade; fully thirty percent reported a change in their family’s religion only six months after initially being asked. In light of these results, it has been called ‘presumptuous’ to even discuss the attitudes of children, if attitudes are understood as ‘relatively enduring predispositions’ (Vaillancourt 1973: 377, 385).

Of course, researchers must often deal with a ‘scarcity of resources for primary data collection’ – this was certainly the case with this study, both in terms of time and finance (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1993: 1203). Due to financial and temporal limitations, the distribution model employed was a reliance on available subjects (ROAS) model, combined with a network snowball approach. Snowballing involves identifying ‘appropriate’ respondents and having them pass either the instrument or contact details along to further respondents (Oppenheim 1992: 43). After this process has begun, ‘network sampling…comes to the fore’, as respondents mine their own personal contact networks for further respondents (Onwuegbuzie and Leech 2007: 112-113).

The surveys were designed with ‘Opinio’ software, and circulated exclusively via the Internet. According to the United Nations’ agency for information technology, 81.6% of Canadians and 80.1% of French have Internet access. This ranks the two 14th and 16th worldwide respectively, ahead of such technological giants as Japan, Hong Kong, and the United States (International Telecommunication Union 2010: 1). Internet survey analysis first appeared in the academic literature in 1996, merely four years after the introduction of the world’s first graphic browser; since then, there has been an explosive proliferation in Internet usage for survey purposes (Couper and Miller 2008: 831). For the purposes of this study, the Internet seemed the most feasible and logical venue for survey distribution. This approach was supplemented by posting links to the survey on the most popular French and Canadian groups of the social networking website Facebook. As of June 2011, the Facebook penetration rate was 49% in Canada and 35% in France, ranking 12th and 52ndin the world, respectively (Social Bakers 2011: 1). Appendix 1 lists the website addresses where the survey was posted.

The surveys were open for responses from 00:00 British Summer Time (BST) on 21 July 2011 through 00:00 (BST) on 8 August 2011, for a total duration of eighteen days. In that period, two hundred and one respondents completed the Canadian survey, and two hundred and twenty-two respondents completed the French version[1]. Two hundred and fifty-four Canadian and two hundred and eighty-eight French surveys were initiated, yielding completion rates of 79.13% and 77.08%, respectively.

Upon completing the survey, respondents had the option of entering their names into a draw for $100 Canadian or €100; one hundred and fifty-eight Canadian respondents (78.61%) and one hundred and sixty-two of the French (72.97%) opted to do so. Survey literature has long recognized that offering a token material prize both incentivises participants, and affirms that ‘their time is valuable and worth compensation’ (Bourque and Fielder 2003: 121).

In cases where nonprobability sampling is employed, it is considered good practice to publish a comparison of the sample’s demographic characteristics with those of the population (Heckathorn 2002, Oppenheim 1992). Appendix 5 compares all demographic survey questions asked against Canadian and French census data; in this way, transparency with regard to the ‘accuracy of [the] sampling operation’ is achieved (Oppenheim 1992: 38).

After data collection was completed, question responses were coded into categories, to facilitate statistical analysis and the identification of patterns (Iarossi 2006: 188). The coding scheme may be found in Appendix 6.

V. FINDINGS & ANALYSIS

General Demographic Observations

As noted above, the survey yielded 201 Canadian and 222 French respondents. Appendix 5 compares the demographic characteristics of the survey respondents against the most recent census data from both countries, and gives a percentage of variation for each category; if the variance exceeds +/- 10%, the figure appears in a greyed-out cell.

In both countries, the category in which respondents were most significantly unrepresentative was that of age. In Canada, 91.54% of respondents were aged sixteen to thirty; 88.74% of French respondents were in the same age bracket – these figures are 66% higher and 64% higher, respectively, than the corresponding proportions of the Canadian and French populations. As an unsurprising result, a similarly inflated proportion of respondents reported low incomes, and being in full-time education as opposed to the labour force. Respondents in both nations also reported significantly higher levels of education than their nations’ populations at large.

The survey respondents were also relatively geographically concentrated. Fully 76.12% of Canadian respondents reported residing in the province of Ontario, compared to only 38.73% of the Canadian population (Statistics Canada 2011). Of these, 73.86% (or 56.22% of the survey total) reported residing in Toronto. In France, 40.54% of respondents reported residing in the region of Ile-de-France, as opposed to only 18.24% of the French population (INSEE 2011). In both cases, nodes of respondents exaggerate the results by a factor of two in and around the countries’ largest cities – Toronto and Paris. Given the nature of the researcher’s personal network connections, this was not an unexpected result.

One further demographic note is worth making: respondents in both nations were far more likely to report having no religion than the Canadian and French populations at large. However, given the overwhelmingly young sample surveyed, this result becomes less surprising, being, as it is, broadly consistent with trends of declining religious practice in the western world, particularly among youth (Collins-Mayo and Dandelion 2010: 25).

The survey results are closely analogous to general proportions of national populations in terms of place of birth, citizenship, and, in Canada, racial identity (due to legal proscriptions, no reliable racial data exists in France). Proportions of men and women are broadly similar to the general population, but women are slightly overrepresented in both nations’ survey results.

In general, this study was most successful at surveying young, highly-educated Canadian and French citizens, clustered primarily around each country’s largest city. The results must be understood and interpreted with this reality in mind. Because of the limitations inherent in the sample obtained, demographically-segmented analysis cannot reasonably be performed. The limited nature of the sample, and thus of extrapolations made from it, will be discussed later in this chapter.

Issue Salience

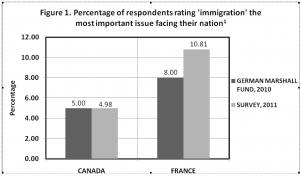

The first question in the survey asks respondents to identify the most important issue facing their nation today. The results are displayed below, compared with the results from an identical question asked in a large-n probability sample poll commissioned by the German Marshall Fund in 2010:

1 Data adapted from German Marshall Fund 2010a: 1

The results suggest that the survey closely mirrored proportions in the general population rating immigration as the most important issue of the day. French respondents are approximately twice as likely as Canadians to rate immigration the principal issue of national concern. However, these numbers lag far behind those selecting economic issues as of prime importance: a total of 53.15% of French and 40.79% of Canadians surveyed selected either ‘economy in general’ or ‘unemployment’ as their top choice. More French respondents also selected education than immigration, making immigration the fourth-highest rated category (of ten) among the French. In Canada, respondents were also more likely to prioritize education, the environment, healthcare, and even ‘my country’s place in the world’, relegating immigration to a distant seventh-place finish. Clearly, the immigration issue is more salient in France than in Canada, a fact which dovetails neatly with findings regarding each nation’s receptiveness to immigration in general.

H1 & H2 – General Views of Immigration

H1: Canadians have generally positive views of immigration.

H2: The French have generally negative views of immigration.

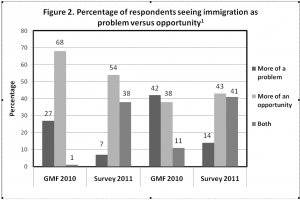

In the present survey, a simple question asking respondents whether they view immigration more as a problem or opportunity serves as a proxy for generalized top-level opinion on immigration. This is an approach which has been adopted from recent research, including studies by Gustin and Ziebarth (2010) and the German Marshall Fund (2010a). The results are presented below, alongside those from the German Marshall Fund’s (GMF) 2010 international survey, presented for sake of comparison:

1 Data adapted from German Marshall Fund 2010a: 54

H1 – Canada

In the Canadian context, a clear majority of respondents considered immigration an opportunity rather than a problem, with 54.23% supporting the former characterization, and only 6.97% the latter. To gain a clearer understanding of Canadian attitudes, results from key cultural and economic opinion questions are analysed. Consider the following:

When asked whether immigration strengthened or weakened national identity, fully 69.16% of respondents selected ‘strengthens considerably’ or ‘strengthens somewhat’. When asked their views on the desirability of multiculturalism, a staggering 90.54% indicated it was generally desirable (with 53.23% selecting ‘very desirable’, and 37.31% ‘somewhat desirable).

From a cultural perspective, Canadian opinions on the normative value of immigration are clearly positive. However, when it comes to opinions about the reality on the ground, results are more nuanced. When asked whether they felt immigrants integrate well into Canadian society or not, 61.20% of respondents felt that they do; however, only 4.48% selected ‘agree strongly’, with 56.72% opting for ‘agree somewhat’. When asked if ‘many immigrants’ hold social values incompatible with modern Canadian society (the vagueness of ‘many’ was intentional, in order to assess response stability), 54.23% agreed, with 11.44% agreeing ‘strongly’, and 42.79% agreeing ‘somewhat’. So, we have the seemingly contradictory result that, while 61.20% of respondents feel that immigrants integrate well, 54.23% think that many of them have social values which are incompatible with modern Canadian society. The implications of this finding are twofold. First, we see evidence for the assertion that questions designed to measure roughly the same attitude vectors may provoke varying responses, based on the precise wording employed (Zaller and Feldman 1992: 579). Secondly, we see that, while overwhelmingly positive about immigration in general, Canadians do express some reservations about the degree to which immigrants integrate culturally.

On the economic side, Canadian attitudes toward immigration are even more unequivocally positive. A full 72.64% of respondents felt that immigrants help fill jobs where there are shortages of workers. When asked if immigration brings down the wages of Canadian-born citizens, 66.76% disagreed. Asked if immigrants are a burden on social services like schools and hospitals, 76.61% of respondents objected. Finally, when asked if immigrants ‘take jobs away from native-born Canadians’, 66.17% disagreed. In no case did the opposite opinion garner more than 15% support, with the remainder explained by neutral opinions, or response refusals. A full 84.08% of respondents thought immigration was important for the economy today (5.48% disagreed), and 82.59% see it as necessary or somewhat necessary for Canada’s ‘future prosperity’ (7.47% disagreed). Generally speaking, Canadian economic support for immigration seems remarkably strong; negative opinions of immigration garnered a mere 5-15% for each economic question posed.

Hypothesis one, that Canadians are generally positive about immigration, is strongly supported by the survey findings. On both cultural and economic axes of opinion, attitudes are robustly receptive and optimistic. From a brief descriptive analysis, economic opinions appear to be even more positive than cultural ones; the relative strength of these opinion vectors will be assessed in a later section.

H2 -France

In France, 42.79% of respondents considered immigration more of an opportunity, versus 14.41% who considered it more of a problem. A full 41.44% opined that it is a bit of both. Results from the same ten questions considered above, in the Canadian context, are examined below, yielding a somewhat surprising outcome.

When asked whether immigration strengthens or weakens national identity, 32.44% of respondents selected ‘strengthens considerably’ or ‘strengthens somewhat’, 28.37% opted for ‘weakens considerably’ or ‘weakens somewhat’, and a plurality, 35.59%, selected ‘neither’. When asked their views on the desirability of multiculturalism, however, 77.03% felt it was either somewhat or very desirable.

From a cultural perspective, French opinions on the normative value of immigration seem mixed. Opinions on the national identity question are neatly divided into thirds, and yet a strong majority favours the ideal of multiculturalism. When it comes to perceptions of immigration in practice, things are complicated further. Asked if immigrants integrate well into French society, 33.33% agree and 41.89% disagree. When asked if ‘many’ immigrants have cultural views incompatible with modern French society, 42.79% agree, and 38.74% disagree. In both cases, a slight plurality of respondents expressed negative views of immigration, but the opposite opinion was expressed in almost equal numbers. The results on the cultural side are polarized, with a slightly negative trend.

On the economic side, French attitudes toward immigration are generally positive; in a surprising result, French economic opinions are often more positive than Canadians’. A full 75.23% of French respondents (versus 72.64% of Canadians) feel that immigrants help fill jobs where there are shortages of workers. A strong 71.62% feel that immigrants do not depress the wages of native-born citizens; 62.16% disagree that immigrants are a burden on social services; and 75.68% disagree that immigrants ‘take jobs’ from native-born workers. Compare these figures with Canada’s 66.76%, 76.61%, and 66.17%, respectively. In other words, French economic negativity outweighs Canadians’ only on the issue of social services; in all other cases, French opinions are moderately more positive.

However, only 67.12% of French respondents feel that immigration is important for France’s economy today, and 66.66% feel it is somewhat or very important for France’s future prosperity (versus 84.08% and 82.59% of Canadians). French attitudes towards immigration are more positive on the economic than on the cultural dimension. Surprisingly, France’s economic views appear to trend slightly more positively than Canada’s; however, while French respondents espouse high levels of positivity for the economic aspects of immigration, they are far less likely than Canadians to see immigration as necessary for achieving economic prosperity.

Evidence for hypothesis two, that the French are generally negative about immigration, is mixed. On the cultural axis, attitudes are polarized, with a negative trend. On the economic axis, opinions are less divergent, and trend positively. From this brief descriptive analysis, French economic opinions appear far more positive than cultural ones; the relative strength of these opinion vectors will be assessed in the section on hypotheses three and four.

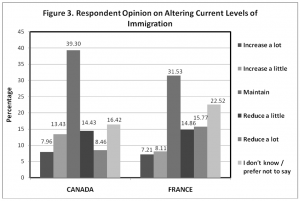

Conclusion

The survey results provide mixed support for the two hypotheses posited. As compared to the German Marshall Fund’s 2010 survey, Canadian opinions are slightly less positive, and French opinions slightly more so. A slight majority of Canadians – 54.23% – view immigration as more opportunity than problem; a plurality of French respondents – 42.79% – feel the same. When asked about altering current levels of immigration, pluralities in both nations favour maintaining current levels, while Canadians are slightly more likely than the French to support increasing levels (21.39% versus 15.32%):

In general terms, Canadian positivity about immigration is strongly supported, although not to the degree found in previous research (e.g. German Marshall Fund 2010b, Simon and Sikich 2007, Jedwab 2006). While Canadians are positive about both economic and cultural dimensions of immigration, they are likely to express more positive views on the economic side. French attitudes toward immigration are more positive here than in previous research (e.g. German Marshall Fund 2010a, Simon and Sikich 2007); while polarized on the cultural dimension, they are notably positive when asked economic questions regarding immigration. We now turn to examine which opinion vector – cultural or economic – is a more strongly related to top-level opinion on immigration.

H3& H4 – Cultural and Economic Factors

H3: Canadian attitudes about immigration are predominately based on economic factors.

H4: French attitudes about immigration are predominantly based on cultural factors.

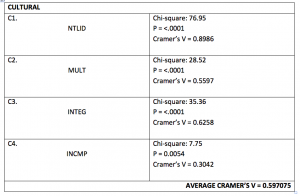

As above, the question on whether respondents consider immigration more an opportunity or problem serves as a proxy for top-level, generalized opinion on immigration. Four key cultural questions (on national identity, multiculturalism, integration, and social values) and four key economic questions (on labour gaps, wage depression, social services, and jobs) serve to represent the two major axes of opinion.

The following four cultural questions were analysed:

C1. In your view, does immigration strengthen or weaken (Canadian/French) national identity? (NTLID)

C2. In general terms, do you think that multiculturalism (the co-existence of multiple ethnic groups within society) is: (MULT)

C3. Immigrants integrate well into (Canadian/French) society. (INTEG)

C4. Many immigrants hold social/cultural values which are incompatible with modern (Canadian/French) society. (INCMP)

The following four questions were analysed on the economic axis:

E1. Immigrants generally help to fill jobs where there are shortages of workers. (FILL)

E2. Immigrants bring down the wages of (Canadian/French)-born citizens. (WAGE)

E3. Immigrants are a burden on social services like schools and hospitals. (SOCS)

E4. Immigrants take jobs away from native-born (Canadian/French) citizens. (JOBS)

These questions parallel ones in the German Marshall Fund’s 2010 International Trends in Immigration study – the most recent cross-national, large-n probability study on attitudes toward immigration. The full coding scheme may be found in Appendix 6. Data was analysed using KADDSTAT, a statistical analysis programme configured for Microsoft Excel.

In order to yield the strongest possible responses, the positive responses (‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree somewhat’) were combined, and the same was done for the two negative responses. Neutral responses and response refusals were discarded from consideration. In terms of the response variable – whether respondents consider immigration an opportunity or a problem – response refusals and answers indicating ‘both’ were likewise discarded from consideration. Response combination is a well-established procedure for yielding more easily-manipulable data. It is also useful for avoiding expected frequencies with values below 5 – this is normally a requirement for chi-square tests (Schuster and Finkelstein 2005: 143).

Contingency tables – with actual frequencies, as opposed to percentages – were then created for all variables; an example follows

Table 1. Sample Chi-square Calculation

Immigrants integrate well into Canadian society.

| OPPORTUNITY | PROBLEM | |

| AGREE | 80 | 2 |

| DISAGREE | 9 | 11 |

The chi-square test is then computed: Chi-square: 35.36

P = <.0001

Finally, the Cramer’s V score is calculated; as a measure of association between nominal variables, it is most suitable for our purposes here. In the example above, the Cramer’s V = 0.6258. Cramer’s V scores (also known as phi-coefficients in 2×2 tables) may be averaged and compared to give an indication of which questions are more strongly associated with our response variable – opportunity versus problem (Sheskin 1997: 660).

The conventional wisdom with regard to chi-square tests on 2×2 tables holds that no expected count should be less than five; in cases such as these, the Fisher-Irwin test is recommended. This rule is violated in the example above, and in several other questions analysed. However, recent research has shown that the Fisher-Irwin test is often ‘far too conservative’, and thus unsuitable for exploratory or preliminary research, such as the current study (Weaver 2009: 1). Indeed, in cases such as these, the chi-square test (without Yates’ correction) has been recommended, so long as ‘all expected numbers’ are at least 1 (Campbell 2007: 3674). This condition is met by all questions under analysis, so we proceed in this vein.

H3 – Canada

Table 2. Cultural Question Chi-squares – Canada

Table 3.Economic Question Chi-squares – Canada

| ECONOMIC | |

| E1. | |

FILL

Chi-square: 14.33P = 0.0002Cramer’s V = 0.4446

E2.

WAGE

Chi-square: 36.58P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.6492E3.

SOCS

Chi-square: 54.28P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.7577E4.

JOBS

Chi-square: 23.42P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.5508

AVERAGE CRAMER’S V = 0.600575

In Canada, the average Cramer’s V scores for cultural and economic vectors differ by only 0.0035. While the average Cramer’s V score for the economic vector is the higher of two – a result which would dovetail neatly with the previous research discussed earlier – it is higher by a relatively insignificant amount. It appears as though, in our sample, answers to economic and cultural answers are roughly equally-related to whether Canadians consider immigration a problem or an opportunity. Insufficient evidence exists to either accept or reject H3, that Canadian opinions are based more on economic than cultural factors.

H4 – France

Table 4. Cultural Question Chi-squares – France

| CULTURAL | |

| C1.

NTLID |

Chi-square: 57.8P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.8934 |

| C2.

MULT |

Chi-square: 42.54P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.6782 |

| C3.

INTEG |

Chi-square: 45.84P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.7291 |

| C4.

INCMP |

Chi-square: 38.3P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.6546 |

|

AVERAGE CRAMER’S V = 0.738825 |

|

Table 5. Economic Question Chi-squares – France

| ECONOMIC | |

| E1.

FILL |

Chi-square: 21.48P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.4847 |

| E2.

WAGE |

Chi-square: 51.82P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.747 |

| E3.

SOCS |

Chi-square: 67.59P = <.0001Cramer’s V = 0.8214 |

| E4.

JOBS |

Chi-square: 10.4P = 0.0013Cramer’s V = 0.3339 |

|

AVERAGE CRAMER’S V = 0.59675 |

|

In France, the average Cramer’s V score for the economic vector is 0.59675, while the score for the cultural vector is 0.738825. In our French sample, answers to cultural questions are significantly more related to whether a respondent considers immigration an opportunity or a problem. Survey results appear to bolster the claim made that cultural opinions matter more than economic ones in the French context; support for H4 exists in our data.

Discussion

The implications of our findings are mixed. Of course, it is not reasonable to assume that cultural and economic attitudes exist in isolation. Indeed, research has shown that, far from being ‘isolated psychological artefacts’, attitudes are often deeply interconnected with a ‘core value system’, or worldview (Oppenheim 1992: 177). In other words, attitudes cannot be divided into test and control groups; economic attitudes may well affect cultural ones, and vice versa. The image of a wheel may prove useful – many have argued that economic hardship serves to exacerbate xenophobia (Fetzer 2011: 3). As the wheel turns, ingrained cultural sentiments may then affect one’s perception of immigration’s economic impact (Sides and Citrin 2007: 478). Staying with the analogy, it does make sense to inquire as to which side of the wheel has more traction. The clearest implication of the findings is simple: more research is needed.

If top-level opinions on immigration are more strongly associated with cultural opinions, policy attention must be paid to issues of integration and acculturation. Indeed, in the French republicanist context, the state’s refusal to collect certain racial and cultural information results in a situation where it is very difficult ‘to address painfully clear group-based disadvantage’ (Hochschild and Cropper 2010: 21). If opinions on immigration are, indeed, based primarily on cultural factors in France, the French government might be wise to reconsider its stance on ‘cultural blindness’, a self-imposed disability which prevents the identification of trends and the targeting of resources. If opinions are based primarily on economic factors, however, policies ensuring that immigrants match labour gaps and are able to prosper – such as a points-based system – make most sense in achieving social cohesion (Antecol et al. 2003: 195). Of course, economically and culturally-optimal policies would ideally be implemented in tandem; what opinion research helps to determine is which should receive priority.

Were the questions analysed exhaustive? Did they perfectly divide and measure opinion based strictly on either cultural or economic axes? In both cases, the answer is clearly ‘no’. Additionally, directional vector orientation may reasonably be inferred (it would seem spurious, for example, to assert that those who consider immigrants a social burden would be more likely to consider immigration an opportunity), but was not computed in the analysis. Further data manipulation is required, once probability samples have been obtained. Indeed, given the nature of the non-probability sample under review, searing scrutiny might well have led to completely misleading inferences – sweeping conclusions drawn from literally handfuls of respondents. To avoid building castles on shifting sands, a conservative approach to our findings is required. Suffice to say that, while interesting patters have emerged from the data, more research is required. We now turn to address some more general limitations of the current research, and improvements that would increase its value.

Limitations & Improvements

Limits on material and temporal resources introduced room for improvement in several areas of survey design and dissemination. First of all, in an ideal research setting, the survey instruments would have been pretested more fully, using focus groups in order to identify any possible problems with the questions. In future, focus groups and open-ended interviews could also be employed in order to derive more categories of economic and cultural opinion to test; this would allow for more powerful inference and more robust conclusions. As has been noted many times by survey researchers, opinions can shift even after trivial alterations to question wording; question design is a highly imprecise science (Zaller and Feldman 1992: 579). To assess response stability, and the extent to which opinions are truly-held rather than transitory, multiple iterations of the survey could be issued, comparing responses to questions with slight, nonsubstantive differences. Finally, to achieve inter-coder reliability, the responses should, in future, be coded and compared by multiple researchers.

In order to improve data quality, and achieve greater certainty of inference, a probability sample would have been employed. This is the single most substantial possible improvement for future research. A probability sample would have allowed a calculation of sampling error, and assured that the sample was more representative of the Canadian and French populations, both in terms of demographic and ideological variance. A larger probability sample would also have allowed for segmented data analysis, and the identification of opinion trends based on particular demographic characteristics; the nature of the current sample would have made such segmentation weak and unsupportable. Segmentation would allow the analysis of important predicted variances; for instance, the opinions of urban versus rural dwellers, men versus women, citizens versus non-citizens, or French-speaking versus English-speaking Canadians. Views on immigrants with different religious beliefs (particularly Muslims, given their elevated relevance in public discourse of recent years) would be another important vein of inquiry. A key segmentation would compare the views of immigrants themselves against those of native-born citizens.

Chain-referral network samples, such as that of the present study, have been criticized on the grounds that they are subject to homophily bias, a distortion which did appear. Chain-referral network samples exclude, by their very nature, the possibility that each unit in the population ‘possesses some chance’ of selection; in light of this, it becomes impossible to precisely determine the ‘accuracy of univariate estimates’ (Best et al. 2001: 132). In short, network samples yield unrepresentative subsets of populations. Indeed, it is intuitive that such samples are often skewed by ‘volunteerism’; this can lead to what is known as a homophily bias. This is a problem in that sociology has long established that personal affiliations are most common among people whose ‘age, education, prestige, social class…race and ethnicity’ are similar; thus, each wave of respondents subsequently biases the next (Heckathorn 2002: 12-13). Homophily bias is evident in the current study in the extent to which respondents were largely homogeneous with regards to age, education, and income.

Survey dissemination via the Internet is also perhaps less than optimal; it has been argued that Internet survey research introduces complications and suffers inherent flaws. Some studies have identified a social cleavage called ‘the digital divide’, separating Internet survey respondents – who tend to be young and score highly on measures of wealth and education – from the general public (Bourque and Fielder 2003: 16). In addition, inferences from Internet surveys rely on two key assumptions: one, that ‘the decision-making processes’ of non-users are the same as those of Internet users, and two, that it is possible to derive representative samples. Best et al. find support for the first assumption, but are sceptical about the second (Best et al. 2001: 131). Again, the non-representativeness of the current study proves its most significant shortcoming.

Finally, survey research itself is not infallible; controversy exists as to the extent to which it measures rather than shapes opinion. The very nature of attitude formation is contested – while most studies conceive of it as a linear process, ‘attitudes may be shaped more like concentric circles or overlapping ellipses or three-dimensional cloud formations’ (Oppenheim 1992: 175). Still more disconcerting, some researchers have argued that most individuals ‘lack meaningful attitudes’ on most subjects, but ‘indulge’ researchers by selecting amongst offered responses in a relatively arbitrary fashion (Converse 1964: 245). The argument has persisted in the literature that ‘most’ people possess only ‘partially consistent’ attitudes; in light of this, it has been posited that surveys ‘shape and channel’ – rather than gauge – opinion. This view is strengthened by findings that attitude reports vary significantly after ‘wholly nonsubstantive changes in question wording’ (Zaller and Feldman 1992: 579). These concerns are not unique to non-probability samples, and there are no simple solutions to the dilemmas they present; however, it is worth remembering that opinion research is a field in continual development, its conclusions are not absolute, and its pursuit may sometimes appear more art than science.

One area in which the inherent difficulty and art of survey design is apparent is in avoiding prestige bias. Prestige – or social desirability – bias is a constant concern in survey research: in an effort to enhance personal standing, respondents may give what they feel is the ‘right’ answer, rather than offer a true opinion (Oppenheim 1992: 139). When attempting to measure sensitive opinions, such as cultural attitudes toward immigration, researchers may encounter a tendency among respondents to be less than forthcoming. Indeed, when presented with the top five source countries for immigration to their country, and asked to select the one whose immigrants are least culturally compatible with Canadian/French society, a full third of Canadians opted not to respond, and four in ten French respondents (a strong plurality) reserved judgment. The sensitivity of cultural attitudes makes attention to question wording even more important.

However, criticisms of the present approach are sometimes overstated; when due consideration is taken of the difficulties inherent in the approach, results can be meaningful and highly valid. Indeed, ‘even the best’ academic surveys suffer from ‘significant biases’ in their sampling; studies have shown that certain demographics (the very wealthy, men, and the elderly, among others) are chronically underrepresented even in ‘probability’ samples (Krosnick 1999: 539). Statistically-speaking, the sampling error for a sample of two hundred respondents is approximately 6.5%, but this is an ‘optimum theoretical’, dependent on a flawless sampling frame and a faultless sampling operation (Oppenheim 1992: 43). While analysis of nonprobability samples naturally involves an element of ‘subjective evaluation’, if the survey process is transparent enough, and detailed demographic comparisons are published, the results can be treated with near-statistical certainty (Heckathorn 2002: 13). In terms of Internet distribution, some scholars now use samples gleaned from ‘heavily trafficked Web sites’ (such as Facebook) as ‘analogous to probabilistic samples’ (Best et al. 2001: 133). Clearly, survey research cannot be treated as gospel, but does provide important insights as to how people ‘respond to real-world political objects’, a crucial concern in any democratic system (Gaines et al. 2007: 2). Indeed, ‘no-one believes that public opinion always determines public policy’, but then again, ‘few believe it never does’ (Burstein 2003: 29). In one recent meta-study of thirty public opinion papers, about ‘three-quarters of the relationships between opinion and policy’ were found to be significant (Burstein 2003: 33). In short, the approach used was the best possible, given the imposed constraints on time and financial resources. In an ideal research setting, the improvements enumerated above would have been implemented; in the absence of these, the best possible remedy is full transparency regarding the exercises of design and dissemination.

VI. FUTURE AVENUES OF RESEARCH

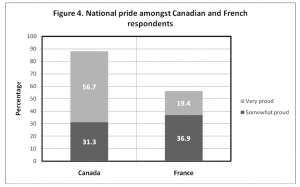

One of the most striking cross-national variances in the survey data obtained relates to national pride. When asked how they felt about being Canadian, a striking 88% of respondents reported feeling either somewhat (31.3%) or very proud (56.7%). On the other hand, only 56.3% of French respondents reported pride in their nationality, with 36.9% opting for ‘somewhat proud’ and only 19.4% for ‘very proud’:

Recent research has indicated that some people view cultural diversity as compatible with – or indeed, intrinsic to – national pride, and that others retain a more exclusionary, nativist conception of national pride (Cameron and Berry 2008: 17). Is patriotism compatible with diversity? Some argue that ‘anti-immigrant sentiments’ should be most pronounced among those with a ‘strong sense’ of national pride (Sides and Citrin 2007: 480). A brief look at Canada, which receives more immigrants per capita than any other nation, and whose population is nearly one-fifth foreign-born, seems to cast this assertion into doubt (Statistics Canada 2011). Inversely, is France’s lower level of positivity about immigration correlated with its lower level of national pride? If it is, why should that be so? The data presently under consideration is insufficient to speak to the issue, but future studies might seek to study immigration attitudes, analysing segments of the population reporting varying degrees of national pride. Clearly, whether broadly-held conceptions of nationalism embrace or reject diversity have implications for social cohesion; both qualitative and quantitative studies in this area would be welcome.

Of course, opinions – whether on immigration, pride, or otherwise – do not spontaneously coalesce; they are shaped and moulded by exogenous influences. The impact of media coverage, as well as issue framing by political elites, may exacerbate the extent to which economic or cultural aspects of immigration are present in the public consciousness (Brader et al. 2008: 976). Conscious, purposive choices made by those in positions of power may well affect national opinion trends. As such, content and discourse analyses on the framing of immigration would be a valuable contribution to knowledge. Paired with survey research which asks about media consumption and political inclination, this would be a very welcome addition to research in the field.

Most importantly, future studies of opinion on immigration should seek to incorporate a longitudinal element. Cross-sectional research designs characterize the field, and yet, with temporal stability a perennial concern in survey research, the approach suffers inherent limitations. Longitudinal studies are particularly crucial in studying attitudes towards immigration, given that immigration is an issue subject to ‘temporal illusion’: its short-term effects may differ significantly from its long-term effects, which may take many years to become evident (Freeman 1995: 883). In other words, immigration is a social reality which unfolds and evolves over time. Despite the necessity of longitudinal research in the area, as of 2010, a ‘comprehensive longitudinal study’ on attitudes toward immigration had not yet been completed (Berry and Sabatier 2010: 206). Longitudinal studies of immigration within nations would be an excellent start. To propose an even more ambitious research agenda, a cross-national longitudinal study of ‘receiving countries’ would prove tremendously valuable. Attitudinal shifts resulting from macro-social change could more easily be understood, analysed, and compared. Comparing views in times of austerity against times of prosperity would yield the most fruitful results. This task would be enormous, but with immigration an increasingly salient political reality, so would be the benefit.

VII. CONCLUSION

In the modern era, Samuel’s ‘cans of hot water’ have become currents spanning oceans and continents. Immigration is a quintessential multi-dimensional issue, impacting virtually every aspect of domestic and foreign affairs. Serious opinion research on the issue has only recently come to the fore, and a key distinction that emerged early in the literature was the ‘relative salience of…economic versus cultural’ vectors of opinions in determining top-level attitudes toward immigration (Brader et al. 2008: 961). The importance of this dichotomy is crucial, as very different policy responses are required depending on whether opinions are predicated more on economic or cultural foundations. Canada is a country where positivity on immigration has been explained through the lens of economic argument; France is a country wherein the primacy of cultural factors has been highlighted. Survey instruments were designed and distributed to Canadian and French respondents, in an effort to measure economic and cultural opinions on immigration. The results suggest a strong relation between cultural opinion and top-level opinion in France, and a mixed scenario in Canada.

In recent decades, survey research in general has improved significantly in its ability to access respondents and their opinions. Opinion research on immigration has come a long way since 1947, when the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees (ICR) commissioned the Social Research Service (SRS) of Michigan State College to conduct a study in Latin America. In the wake of the Second World War, the ICR wished to relocate European refugees to Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru, and sought to predict how they would be received. The SRS conducted 107 telephone interviews in total, split among the three nations; the results suggested an overwhelmingly welcoming disposition among the Latin Americans (ninety-seven percent of urban respondents favoured receiving the European migrants). However, compounding the folly of the small sample, only 5% of the population in question had telephone access at the time of the study (Loomis 1947: 30-31). Inferences drawn from such crude measures seem ludicrous today, and yet there is still much progress to be made. Fifty years ago, public opinion as a ‘social and political process’ was called ‘almost an uncharted field’; today, more has been charted, but not necessarily understood (Dion 1962: 574). However, one of the most important theoretical advances in recent years has been a move towards disaggregating attitudes, in an effort to understand the nature (and relative importance) of their constituent components.

When considering economic and cultural determinants of top-level opinion, it is clear that ‘both sets’ of factors matter (Mayda 2004: 25). However, it has been called ‘fruitless’ to ‘seek general validity in either’; an investigation of their relative power is required (Hooghe and Marks 2004: 418). The present study has attempted to make a step down this path. The comparative exercise is crucial, as different policy implications flow from interest-generated or ideology-generated attitudes (Wilkes et al. 2008: 304). The implications of the research are inherently pragmatic.

However, moral questions are also deeply embedded in issues of immigration. As alluded to earlier, Canada’s points-based immigration system leads to the admission of high numbers of educated, qualified new citizens. Social harmony through economic prosperity: the argument runs that this policy is largely responsible for positive views of immigration in Canada. Notably, some have suggested implementing an identical points system in France (Defoort and Docquier 2007: 713). However, scholars have questioned the points approach on humanitarian grounds, arguing that such an inflexible focus on economic immigration is unbefitting such a large and wealthy country, making Canada a stingy global citizen. They concede, however, that although the approach may be normatively questionable, as far as social cohesion is concerned – it works (Hochschild and Cropper 2010). The questions raised by immigration are both moral and pragmatic, implicating normative values at every turn.

Ideally, the present study would have been carried out with more pretesting and intercoding, and – most importantly – with a probability sample. The results and analysis are necessarily truncated because this proved unfeasible given the constraints imposed. However, survey evidence suggests that assumptions about the relative salience of cultural and economic determinants of opinion on immigration may be well-founded – at least insofar as young, urban respondents are concerned. Despite the sample’s limitations, the implications of this finding are important; highly-educated urban youth tend to dominate the political classes in later life (Putnam 1976). As such, the opinions of the young do merit special attention. The topic deserves, and requires, further elucidation.

However, the major contribution of this study has been to introduce a cross-national element to studies of component attitudes on immigration. Some studies emphasize the importance of economic reasons in determining such attitudes, while other studies stress cultural factors. Studies in the literature have compared these dimensions within but not across nations (Fetzer 2011: 2). As such, this study represents a small but significant step in a new direction. More research is needed here, to further develop and advance understanding of the reasons underlying opinions on immigration. As the greatest demographic upheaval in human history continues unabated, the consequences promise to be earth-shaking, impacting politics at every level. An understanding of how best to accommodate the resulting social change involves understanding why people feel the way they do about immigration; this understanding will doubtless prove increasingly vital in the years to come.

Bibliography

Antecol, Heather, Deborah Cobb-Clark and Stephen Trejo. “Immigration Policy and the Skills of Immigrants to Australia, Canada, and the United States. “The Journal of Human Resources 38 (2003): 192-218. Print.

Berry, John and Colette Sabatier. “Acculturation, Discrimination, and Adaptation among Second Generation Immigrant Youth in Montreal and Paris. “International Journal of Intercultural Relations 34 (2010): 191-207. Print.

Berry, John. “Mutual Attitudes among Immigrants and Ethnocultural Groups in Canada. “International Journal of Intercultural Attitudes 30 (2006): 719-734. Print.

Best, Samuel, Brian Krueger, Clark Hubbard, and Andrew Smith. “An Assessment of the Generalizability of Internet Surveys. “Social Science Computer Review 19 (2001): 131-145. Print.

Blake, Donald. “Environmental Determinants of Racial Attitudes among White Canadians. “Canadian Journal of Political Science 36 (2003): 491-509. Print.

Bourque, Linda and Eve Fielder. How to Conduct Self-Administered and Mail Surveys. 2nd. London: SAGE Publications, 2003. Print.

Brader, Ted, Nicholas Valentino and Elizabeth Suhay. “What Triggers Opposition to Immigration? Anxiety, Group Cues, and Immigration Threat. “American Journal of Political Science 52 (2008): 959-978. Print.

Breunig, Christian and Adam Luedtke. “What Motivates the Gatekeepers? Explaining Governing Party Preferences on Immigration. “Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions 21 (2008): 123-146. Print.

Burstein, Paul. “The Impact of Public Opinion on Public Policy: A Review and an Agenda.” Political Research Quarterly 56 (2003): 29-40. Print.

Cameron, James and John Berry. “True Patriot Love: Structures and Predictors of Canadian Pride.” Canadian Ethnic Studies 40 (2008): 17-41. Print.

Campbell, Ian. “Chi-squared and Fisher-Irwin Tests of Two-by-Two Tables with Small Sample Recommendations.” Statistics in Medicine 26 (2007): 3661-3675. Print.

Ceobanu, Alin and Xavier Escandell. “Comparative Analyses of Public Attitudes toward Immigrants Using Multinational Survey Data: A Review of Theories and Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (2010): 309-328. Print.

Citrin, Jack and John Sides. “Immigration and the Imagined Community in Europe and the United States.” Political Studies 56 (2008): 33-56. Print.

Collins-Mayo, Sylvia and Pink Dandelion. Religion and Youth. 1st. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2010. Print.

Converse, Philip. “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics. “Ideology and Discontent.” Ed. David Apter. New York: Free Press, 1964. Print.

Couper, Mick and Peter Miller. “Web Survey Methods.” Public Opinion Quarterly 72 (2008): 831-835. Print.

Defoort, Cécily and Frédéric Docquier. “Impacte d’une Immigration «choisie» sur la Fuite de Cerveaux des Pays d’Origine.” Revue économique 58 (2007): 713-724. Print.

Delli Carpini, Michael and Scott Keeter. “Measuring Political Knowledge: Putting First Things First.” American Journal of Political Science 37 (1993): 1179-1206. Print.

Dion, Leon. “Democracy as Perceived by Public Opinion Analysis.” The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 28 (1962): 571-584. Print.

Drage, Geoffrey. “Alien Immigration.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 58 (1895): 1-35. Print.

Dufferin and Ava, Frederick Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood. “Canada: The Place for the Emigrant.” Toronto, ON: Foreign and Commonwealth Office Collection, 1874. Web. Available: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/60229618>

Entorf, Horst and Nicoleta Minoiu. “What a Difference Immigration Policy Makes: A Comparison of PISA Scores in Europe and Traditional Countries of Immigration.” German Economic Review 6 (2005): 355-376. Print.

Esses, Victoria, Kay Deaux, Richard Lalonde, and Rupert Brown. “Psychological Perspectives on Immigration.” Journal of Social Issues 66 (2010): 635-647. Print.

Facchini, Giovanni and Anna Maria Mayda. “From Individual Attitudes Towards Migrants to Migration Policy Outcomes: Theory and Evidence.” Economic Policy 23 (2008): 651-713. Print.

Fassin, Didier. “Compassion and Repression: The Moral Economy of Immigration Policies in France.” Cultural Anthropology 20 (2005): 362-387. Print.

Fetzer, Joel. “The Evolution of Public Attitudes toward Immigration in Europe and the United States.” San Domenico di Fiesole, Italy: European University Institute, 2011. Web. Available: <http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/17840/EU-US%20Immigration%20Systems%202011_10.pdf>

Fortin, Jessica and Peter John Loewen. “Prejudice and Asymmetrical Opinion Structures: Public Opinion toward Immigration in Canada.” Winnipeg, MB: Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, 2004. Web. Available: <http://www.cpsa-acsp.ca/papers-2004/Loewen-Fortin.pdf>

Freeman, Gary. “Modes of Immigration Politics in Liberal Democratic States.” International Migration Review 29 (1995): 881-902. Print.

Furlong, Abbey. “Cultural Integration in the European Union: A Comparative Analysis of the Immigration Policies of France and Spain.” Transnational Law and Contemporary Problems 19 (2010): 680-703. Print.

Gaines, Brian, James Kuklinski and Paul Quirk. “The Logic of the Survey Experiment Reexamined.” Political Analysis 15 (2007): 1-20. Print.

German Marshall Fund. “Transatlantic Trends: Immigration, 2010.” Washington DC: German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2010a. Web. Available: <http://trends.gmfus.org/immigration/doc/TTI2010_English_Key.pdf>

German Marshall Fund. “2010 Country Specific Results – CANADA.” Washington DC: German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2010b. Web. Available: <http://trends.gmfus.org/immigration/doc/TTI2010_CANADA.doc>

Girard, Alain. “Opinion Publique, Immigration et Immigrés.” Ethnologie Française 7 (1977): 219-228. Print.

Green, Eva. “Who Can Enter? A Multilevel Analysis on Public Support for Immigration Criteria across 20 European Countries.” Group Processes Intergroup Relations 12 (2009): 41-60. Print.

Gustin, Delancey and Astrid Ziebarth. “Transatlantic Opinion on Immigration: Greater Worries and Outlier Optimism.” International Migration Review 44 (2010): 974-991. Print.

Hainmueller, Jens and Michael Hiscox. “Educated Preferences: Explaining Attitudes toward Immigration in Europe.” International Organization 61 (2007): 399-442. Print.

Heckathorn, Douglas. “Deriving Valid Population Estimates from Chain-Referral Samples of Hidden Populations.” Social Problems 49 (2002): 11-34. Print.

Hein, Jeremy. “The French Melting Pot: Immigration, Citizenship, and National Identity.” American Journal of Sociology 102 (1997): 1751-1753. Print.

Hiebert, Daniel. “Winning, Losing, and Still Playing the Game: The Political Economy of Immigration in Canada.” Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 97 (2006): 38-48. Print.

Hochschild, Jennifer and Porsha Cropper. “Immigration Regimes and Schooling Regimes: Which Countries Provide Successful Immigrant Incorporation?” Theory and Research in Education 8 (2010): 21-61. Print.

Hooghe, Lisbet and Gary Marks. “Does Identity or Economic Rationality Drive Public Opinion on European Integration?” Political Science and Politics 37 (2004): 415-420. Print.

Iarossi, Giuseppe. The Power of Survey Design: A User’s Guide for Managing Surveys, Interpreting Results, and Influencing Respondents.1st. Washington DC: World Bank Publications, 2006. Print.

INSEE. “Résultats du recensement de la population – 2008.” Paris: Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques, 2011. Web. Available: <http://www.recensement.insee.fr/home.action>

International Telecommunications Union. “Internet Users.” Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations, 2010. Web. Available: <http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/material/excel/2010/InternetUsersPercentage00-10.xls>

Jedwab, Jack. “Keep on Tracking: Immigration and Public Opinion in Canada?” Vancouver, BC: Association for Canadian Studies, 2006. Web. Available: <http://www.canada.metropolis.net/events/Vancouver_2006/Presentation/WS-032406-1530-Jedwab.ppt>

Krosnick, Jon. “Survey Research.” Annual Review of Psychology 50 (1999): 537-567. Print.

Lauer, Charlotte. “Educational Attainment in France and Germany.” ZEW Economic Studies 30 (2005): 37-93. Print.

Loomis, Charles. “Trial Use of Public Opinion Survey Procedures in Determining Immigration and Colonization Policies for Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru.” Social Forces 26 (1947): 30-35. Print.

Martin, Philip. “Comparative Migration Policies.” International Migration Review 28 (1994): 164-170. Print.

Mayda, Anna Maria. “Who Is Against Immigration? A Cross-Country Investigation of Individual Attitudes toward Immigrants.” Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor, 2004. Web. Available: <http:ftp.iza.org/dp1115.pdf>

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony and Nancy Leech. “A Call for Qualitative Power Analyses.” Quality and Quantity 41 (2007): 105-121. Print.

Oppenheim, A. N. Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement. 2nd. London: Pinter Publishers, 1992. Print.

Palmer, Howard. “Mosaic versus Melting Pot?: Immigration and Ethnicity in Canada and the United States.” International Journal 31 (1976): 488-528. Print.

Presser, Stanley, Mick Couper, Judith Lessler, Elizabeth Martin, Jean Martin, Jennifer Rothgeb, and Eleanor Singer. “Methods for Testing Evaluating Survey Questions.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 68 (2004): 109-130. Print.

Putnam, Robert. The Comparative Study of Political Elites. 1st. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1976. Print.

Rayside, David. “Immigration – letter.” Message to Dylan White. 17 March 2011. E-mail.

Samuel, Herbert. “Immigration.” The Economic Journal 15 (1905): 317-339. Print.

Schuster, Jack and Martin Finkelstein. The American Faculty: The Restructuring of Academic Work and Careers. 2nd. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. Print.

Sheskin, David. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures. 2nd. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1997. Print.

Sides, John and Jack Citrin. “European Opinions About Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests, and Information.” British Journal of Political Science 37 (2007): 477-503. Print.

Sills, Stephen and Chunyan Song. “Innovations in Survey Research: An Application of Web-Based Surveys.” Social Science Computer Review 20 (2002): 22-30. Print.

Simon, Rita and Keri Sikich. “Public Attitudes toward Immigrants and Immigration Policies across Seven Nations.” International Migration Review 41 (2007): 956-962. Print.

Social Bakers – Social Media Statistics. “Facebook Statistics by Country.” London, UK: Socialbakers Ltd, 2011. Web. Available: <http://www.socialbakers.com/facebook-statistics/>

Statistics Canada. “2006 Census Release Topics.” Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, 2011. Web. Available: <http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/rt-td/index-eng.cfm>

Stead, Robert. “Canada’s Immigration Policy.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 107 (1923): 56-62. Print.

Thompson, John and Morton Weinfeld. “Entry and Exit: Canadian Immigration Policy in Context.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 538 (1995): 185-198. Print.

Vaillancourt, Pauline Marie. “Stability of Children’s Survey Responses.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 37 (1973): 373-387. Print.

Weaver, Bruce. “Assumptions/Restrictions for Chi-Square Tests on Contingency Tables.” Thunder Bay, ON: Lakehead University, 2009. Web. Available: <https://sites.google.com/a/lakeheadu.ca/bweaver/Home/statistics/notes/chisqr_assumptions>

Wilkes, Rima, Neil Guppy and Lily Farris. “’No Thanks, We’re Full’: Individual Characteristics, National Context, and Changing Attitudes Toward Immigration.” International Migration Review 42 (2008): 302-329. Print.

Zaller, John and Stanley Feldman. “A Simple Theory of the Survey Response: Answering Questions versus Revealing Preferences.” American Journal of Political Science 36 (1992): 579-616. Print.

[1] Top-level summary data reports may be requested from the author. They have been omitted from the appendices for the sake of brevity.

___

Written by: Dylan White

Written at: UCL

Written for: Dr J. Hudson

Date Written: September 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Incubators of Terror: Anatomising the Determinants of Domestic Terrorism

- Institutionalised and Ideological Racism in the French Labour Market

- “Fake It Till You Make It?” Post-Coloniality and Consumer Culture in Africa

- Europe’s Biggest Eurosceptics: Britain and Support for the European Union

- Environmental Protection or Economic Growth: What Do Nigerians Think?

- Women in International Migration: Transnational Networking and the Global Labor Force