“If This is the Answer, What is the Question?” is a panel game from a BBC improvised comedy program Mock the Week – from the given answer, panelists rather comically guess the question. In one episode, the panel was given the answer “Cheese, Wine and Rubbish”, to which one panelist answered “What three words best describe France?”[1]

All comical and potentially offensive elements aside, this is a good exercise to identify a variety of stereotypes in our society. Likewise, when we use this exercise to guess the question or hypothesis from the given case studies, we identify potential biases and strengthen our research designing. In particular, the author emphasizes the importance of case selection in comparative studies, utilizing examples from popular culture in former-Communist societies. Furthermore, the same argument highlights the possibility to re-model the research question when the case studies do not match with the original hypotheses. Thus, the rest of this essay will be divided into three parts.

Firstly, the overview of pair-comparison underlines the source of new knowledge (epistemology) deriving from the comparative method. Secondly, the comparison between “Pussy Riot” from Moscow and “the Plastic People of Universe” from Prague demonstrates how the checking tool (“If This is the Case Study, What is the Research Question?”) functions. The last section provides some tips on case selection without undermining authoritative works in research designing.

On comparative method, MacIntyre states: “we shall be able to distinguish between genuine law-like generalizations and mere de facto generalizations which hold only of the instances so far observed.”[2] The statement sounds elementary when one compares voting behaviors in Mexico and Luxembourg: socio-political environments in two countries are so diverse that we cannot comfortably form scientific analyses. Nonetheless, MacIntyre’s statement becomes serious when we consider comparative Area Studies, e.g. case studies from a similar socio-political environment. If presidential elections in Russia and Belarus are the case studies, what is the hypothesis? One can suggest that in post-Communist societies, voters tend to prefer paternal figures as their leaders. Perhaps, theories and previous studies, such as national surveys, may further support the argument.[3] Yet, this is a de facto generalization, thereby the beauty of comparative method is lost. The selection bias simply collect two similar countries (i.e. Russia and Belarus) in order to confirm the first impression of the researcher – either the case alone can structure the argument, and the additional case does not necessarily bring additional knowledge.[4]

Rather, it is more interesting to see how socio-political differences in Russia and Belarus surface in their assumed similar political behaviors. For example, given different degrees of economic dependency on foreign goods and services in the two countries, why does the nationalist rhetoric still thrive in their political scene? This research question indirectly refers to the theory of democratic peace and potentially distinguishes asymmetric dependency from inter-dependency. Such re-modeling of research questions is essential for Area Studies scholars who tend to observe some “regional patterns” (thus, more likely to be trapped into MacIntyre’s de facto generalizations). In other words, finding two similar cases neither soundly concludes nor automatically commences comparative analyses. Let us consider the examples of “Pussy Riot” from Moscow and of “the Plastic People of Universe” from Prague.

In February 2012, a female punk band “Pussy Riot” performed an impromptu concert in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow. Because of their masks, members were not immediately identified. Following months, police’s efforts to arrest the band members for “hooliganism” were described as “the witch hunt,”[5] and international organizations such as Amnesty International accused Moscow for yet another incident of human rights violation.[6] Furthermore, as the band played anti-Putin songs, international media portrayed the case as a part of the lengthy anti-regime protests in Russia and read political motivations behind the actions taken by the authority.[7] The concert in the Cathedral was taken also as a symbol of protest against Patriarch Kirill I of Moscow and his Russian Orthodox Church, for publicly supporting President Putin. Thus, the condemnation of “Pussy Riot” by Patriarch was seen as a sign of pro-Putin sentiment rather than the expression of general conservatism within the Orthodox Church.[8]

“The Plastic People of Universe” is a rock band from Prague formed in 1968 when the country was still called Czechoslovakia. The year 1968 was a turbulent moment for the country: under the slogan “socialism with a human face,” First Secretary of the Communist Party Alexander Dubček carried out partial liberalization reform in order to revitalize the Czechoslovak economy. The Soviet leadership, however, clashed the movement by mobilizing the Warsaw Pact force into Czechoslovakia, known as the “Prague Spring.” In the midst of the following political “normalization” process, “the Plastic People of Universe” continued to play underground including at the various music festivals. One of these festivals was held in 1976 when the Party arrested them for public nuisance, and the band members faced the imprisonment. Following the arrest of the band, Václav Havel and other intellectuals formed Charter 77 demanding the implementation of various human rights provisions.[9] According to their claim, Czechoslovakia had signed the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 which protected peaceful assembly of people – thus, “the Plastic People of Universe” must be released immediately. Charter 77 was a highly political movement throughout the next decade, and many of its members became the leaders of the post-Communist government in the Czech Republic.

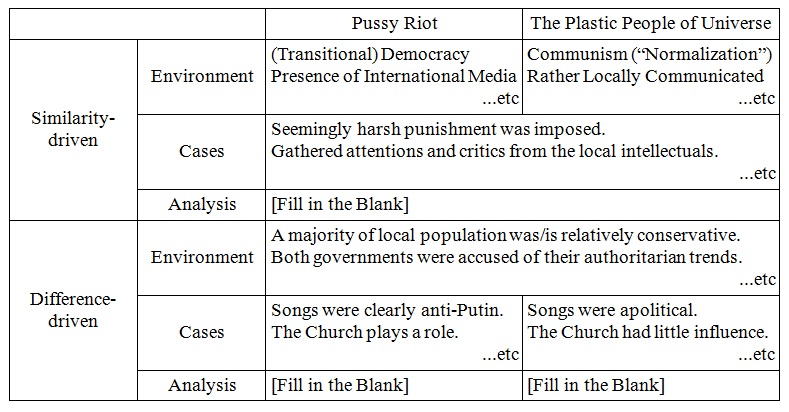

If “Pussy Riot” and “the Plastic People of Universe” are the case studies, what is the research question? To begin with, we can construct a chart listing variables in each case, keeping in mind the lessons from MacIntyre. The chart is horizontally divided into similarity- and difference-driven comparative methods. Each method matches similarities or differences between two cases with relevant observations of socio-political environments (including institutions) which potentially lead to “genuine law-like generalizations.” Items listed in the chart are some examples derived from this comparative case study.

Table 1: Example Exercise of “If This is the Case Study, What is the Research Question?”

The similarity-driven approach may suggest the formation of a Charter-77-like movement in contemporary Russia. In particular, as both punk and rock music are followed by younger generations, their participation to the discussion on human rights is a positive candidate for generalizations. Another angle of observation may suggest that conservative culture leads to the acceptance of harsh punishment against the music bands in general. Either hypothesis, however, over-reaches the epistemological limits of a pair-comparison. Due to the proximity of socio-political environments in Russia and the then Czechoslovakia, the notion of “similarity leads to similarity” remains in the realm of correlation, but not of causation. Likewise, the logic of “difference leads to difference” does not seem to belong to the filed of political science. Here comes re-modeling.

Let us consider the shuffled chart below. It reads as follows: given socio-political differences (or similarities) in two environments, how can we explain similarities (or differences) between two cases? For example, why did Moscow treat Pussy Riot so harshly like a Communist government, given increasing attentions from international media and risks of loosing reputation as a democratic society in transition? Note the true epistemology of generalization does not lie in Russian domestic politics – rather, it questions the assumed explanatory capacity of international culture, extrinsic democratization, and reputation of governments which are often utilized in the English School of International Relations and beyond.

Table 2: Shuffling and Re-modeling Exercise

Apples and oranges are incomparable unless we establish the concept of “fruits.” In other words, “If This is the Case Study, What is the Research Question?” encourages a certain degree of inductive thinking in Comparative Politics. We usually initiate research with analytical questions and hypotheses in our mind. During the data collection, we form a mind-chart similar to Table 1, and we may realize the research is trapped into the de facto generalizations. Re-modeling (Table 2) allows us to break though this epistemological deadlock by observing a general analysis from the given cases (induction). Surely, re-modeling is not the only cure; collecting further data to strengthen the original research question is just another example. Yet, the cases similar to the above “Pussy Riot” and “the Plastic People of Universe” do not occur so often. Thus, a re-modeled comparison seems to be a practical and reasonable solution especially for Area Study scholars whose case selection is geographically often limited.

—

Tom Hashimoto was a Lecturer (EU-Russia Relations and European Integration) at EuroCollege, the University of Tartu. Recently, he has edited a JCER special issue EU-Russia Relations and International Society Theory. He is also the founder of an academic consulting agency, e-supervisor. He is currently pursuing a DPhil in Geography (geo-economics of the EU) at the University of Oxford. Contact: tomoyuki@ut.ee / tom.hashimoto@yahoo.com.

[1] The correct answer according to the program is “What everyday products are being used to develop new fuels for cars?”

[2] MacIntyre, A. (1972) “Is a Science of Comparative Politics Possible?” in Runciman, W. C. & Skinner, Q. (eds.) Philosophy, Politics and Society. Blackwell, pp. 8-26.

[3] Theory plays an important role in Comparative Politics as it indirectly introduces numerous case studies from previous studies. See Kohli, A. et al. (1995) “The Role of Theory in Comparative Politics: A Symposium,” World Politics, 48 (1), pp. 1-49.

[4] This is one argument for the so-called “small-n comparison” over “pair-comparison.” Yet, given limited space allocated to each journal article, a pair-comparison is still practical in deepening each case analysis.

[5] Davidoff, V. (2012) “The Witch Hunt Against Pussy Riot,” Opinion, The Moscow Times. 24 June. Available at: http://www.themoscowtimes.com/opinion/article/the-witch-hunt-against-pussy-riot/460968.html.

[6] Michaels, S. (2012) “Amnesty Calls on Vladimir Putin to Release Pussy Riot Immediately,” Culture, The Guardian. 5 April. Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2012/apr/05/amnesty-vladimir-putin-pussy-riot.

[7] Baczynska, G. (2012) “Russian Police Detain Pussy Riot Supporters,” World, Reuters Africa. 20 June. Available at: http://af.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idAFBRE85J0OE20120620.

[8] Baczynska, G. (2012) “Russian Court Refuses to Free Pussy Riot Members,” Reuters. 20 June. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/06/20/entertainment-us-russia-czech-pussyriot-idUSBRE85I1KC20120620.

[9] Bolton, J. (2012) Worlds of Dissent: Charter 77, The Plastic People of Universe, and Czech Culture under Communism. Harvard University Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- International Travel Is a Risky Business: Research, Study, & Proselytizing

- Opinion – The Question of Remedial Secession in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh

- Opinion – Transgressive Pedagogy in International Studies: A European Case Study

- Lula Is Back on the International Stage, or Is He?

- Opinion – Is Standing by the Minsk II Agreement Worth It?

- Everyone is Talking About It, but What is Geopolitics?