Earlier this week—on 6 February at 11.22am to be precise—a photograph began circulating on Twitter that showed the UK Foreign Secretary, William Hague, sitting and talking with two members of the Falklands Islands Legislative Assembly (MLAs Dick Sawle and Jan Cheek). Nothing unusual in that. The Falkland Islands are, after all, an Overseas Dependency of the UK and the Foreign Secretary regularly meets representatives from the Islands and elsewhere. Official photographs of such meetings are an equally routine component of life on the diplomatic stage. This particular photograph, however, is less than straightforward: not so much a record of who was present than a profound statement of absence. The emptiness of the red leather armchair, awkwardly dominating the foreground of the image, is hardly subtle. The intended occupant of the chair, if things had gone to plan, was the Argentine Foreign Minister, Hector Timerman. In the aftermath of the meeting, which took place in Hague’s office in the Foreign & Commonwealth Office, Jan Cheek MLA is reported to have said: ““Sadly, there was an empty chair in the room, as the Argentine Foreign Minister declined to attend. We are disappointed, but hardly surprised. Argentina prefers to disregard our existence, rather than engage constructively with the people who have lived on the Falkland Islands for so many generations”.

Earlier this week—on 6 February at 11.22am to be precise—a photograph began circulating on Twitter that showed the UK Foreign Secretary, William Hague, sitting and talking with two members of the Falklands Islands Legislative Assembly (MLAs Dick Sawle and Jan Cheek). Nothing unusual in that. The Falkland Islands are, after all, an Overseas Dependency of the UK and the Foreign Secretary regularly meets representatives from the Islands and elsewhere. Official photographs of such meetings are an equally routine component of life on the diplomatic stage. This particular photograph, however, is less than straightforward: not so much a record of who was present than a profound statement of absence. The emptiness of the red leather armchair, awkwardly dominating the foreground of the image, is hardly subtle. The intended occupant of the chair, if things had gone to plan, was the Argentine Foreign Minister, Hector Timerman. In the aftermath of the meeting, which took place in Hague’s office in the Foreign & Commonwealth Office, Jan Cheek MLA is reported to have said: ““Sadly, there was an empty chair in the room, as the Argentine Foreign Minister declined to attend. We are disappointed, but hardly surprised. Argentina prefers to disregard our existence, rather than engage constructively with the people who have lived on the Falkland Islands for so many generations”.

An empty chair there may have been, but the Timerman’s absence was not unexpected. He had, after all, publically retracted his acceptance of the FCO ‘s invitation after learning that Falkland Islanders should be present at the meeting. Interviewed by the Guardian newspaper, the Foreign Minister went on to assert that the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) would be under Argentine control within ‘twenty years”. The period of time in question is significant because it reflects another milestone in the history of the predominantly English speaking community living in the Falkland Islands—200 years of continuous occupation (1833-2033). Warming to his theme, and speaking with the BBC and two British newspapers, Senor Timerman asserted that the UK government ‘occupied’ the Islands because of ‘access to oil and natural resources’ and that the Islanders were an imposed community. By refusing to participate in the meeting where a chair had been made available for him, the Argentine Foreign Minister wanted to show the wider world that he—and by extension Argentina—refused to recognise the political agency of the elected Falkland Islands Government. As events in London this week have shown, this is not always a straightforward refusal. Following an address to the House of Common’s ‘All Party Argentina Group’, a member of the Falkland Islands Government attempted to present Mr Timerman with a letter and a copy of the recently published booklet ‘Our Islands Our History’. While the offer was refused, the ‘meeting’ was certainly indicative of the complex diplomatic dance being undertaken by the Argentine Foreign Minister.

What might we learn from the Foreign Minister’s visit to London? As has become clear, once again, the UK and Argentina have fundamentally different starting positions in the ongoing dispute over the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands. The UK places greater emphasis on the agency of the community living in the Falkland Islands while Argentina continues to portray the dispute as one between two state parties where territorial and resource interests prevail. We might also note the increasing confidence of the elected members of the Falkland Islands Assembly (MLAs): door-stepping the Argentine Foreign Minister; staging their own form of ‘statecraft’ using the device of the ‘the letter’ (just as the Argentine President did recently in UK newspapers); and ultimately seeking to unsettle the Argentine Foreign Minister in the House of Commons. All of this seems a long way from the now out-dated view of Falkland Islanders as remote and dependent upon others to project their interests and wishes.

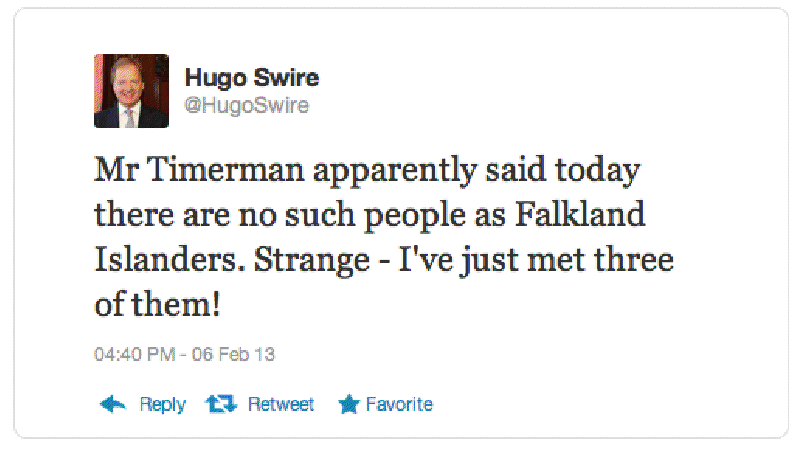

But there is another notable aspect to this episode involving an empty chair, a letter, and an Argentine Foreign Minister: the use of social media by the British government, especially the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, to actively challenge the statements and actions of the Argentine government. It is worth noting that it was from William Hague’s personal Twitter account (@williamjhague) that the ‘empty chair’ first entered the public domain at 11.22am on 6 February. It has since been retweeted 90 times, including to the 20,000+ followers of @falklands_utd (a Falklands advocacy group) as well as 118,000 followers of the official FCO twitter account (@foreignoffice). In a similar vein, the UK Foreign Office Minister, Hugo Swire, tweeted shortly after meeting with Falkland Islands representatives:

“Mr Timerman apparently said today that there are no such people as Falkland Islanders. Strange – I have just met three of them. “

Hague and Swire are highly active tweeters and it is noticeable how their tweets have the capacity to generate a barrage of responses and exchanges from respondents around the world.

Hague and Swire are highly active tweeters and it is noticeable how their tweets have the capacity to generate a barrage of responses and exchanges from respondents around the world.

In addition to the personal accounts of politicians-cum-diplomats, the Foreign Office has embraced the digital diplomacy agenda and has been proactive in circulating stories about the Falkland Islands community, especially in Latin America. The FCO now operates dedicated twitter feeds for audiences in Chile, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, maintains ambassadorial blogs, photo-streams, and interactive websites. As Tom Fletcher, the UK Ambassador to Lebanon and vocal exponent of digital diplomacy, has observed, these online activities are not simply novel means of communication; they have the capacity to change the ways in which diplomacy is conducted in the 21st century:

“In the past we could meet people, do traditional media, map influence, engage civil society. But social media changes the context completely – we no longer have to focus solely on the elites to make our case, or to influence policy. This is exciting, challenging and subversive. Getting it wrong could start a war: imagine if a diplomat misguidedly tweeted a link to that offensive anti-Islam film. Getting it right has the potential to rewrite the diplomatic rulebook.”

Digital diplomacy brings new opportunities, but equally new responsibilities that are increasingly divested to the level of the individual ‘digital diplomat’. While the tweeting of a staged photograph involving an empty chair may not provoke the same intensity of reaction as the tweeting of an “offensive anti-Islam film”, it is nonetheless important to question whether this kind of instant media-sharing marks a significant shift in diplomatic culture—to one that is, perhaps, more tabloid and driven by the pseudo-journalistic temptations of being ‘subversive’ and ‘exciting’. We are, therefore, confronted with some important questions, not least: do we want our diplomats to be journalists and to employ such journalistic instruments in the national cause? And what are the alternatives in an era of social media?

Coda: Since writing this article, the Foreign & Commonwealth Office have published the ‘official’ account of the meeting between William Hague and the Falkland Islands representatives. The accompanying image is familiar, but noticeably the empty chair has been cropped out of the frame. This act of cropping may reveal a difference in perceived visual culture of Twitter and other kinds of online platforms. Perhaps, too, it reveals distinctions between the diplomatic practices of the Foreign Secretary (who is, after all, a politician) and that of the civil servants within the Foreign & Commonwealth Office.

—

Dr. Alasdair Pinkerton and Prof. Klaus Dodds lecture at Royal Holloway, University of London. Read more of GPS: Geopolitics and Security – Critical Perspectives From Royal Holloway.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Digital Decay and the Global Politics of Virtual Infrastructure

- Opinion – Twitter as an Orwellian Global Editor

- The Twitter Prisoner Dilemma and the Future of Digital Diplomacy

- Opinion – Virtual Diplomacy in India

- Tech-Diplomacy: High-Tech Driven Rhetoric to Shape National Reputation

- The Mindful Diplomat: How Can Mindfulness Improve Diplomacy?