To find out more about E-IR essay awards, click here.

“When a robot dies, you don’t have to write a letter to its mother” – P.W.Singer[1]

“The measure of a man’s bravery is not archery; rather he who stands fast in his rank and gazes unflinchingly at the swift gash of the spear is the brave man” – Euripides

On 21 December 2012, the UK High Court blocked an appeal by Noor Khan, whose father was killed in a US drone attack in the North Waziristan region of Pakistan, to investigate whether British intelligence has been involved in assisting the CIA in carrying out such attacks. Khan’s case includes the argument that the US’ use of drones has resulted in increasing civilian deaths, raising the question of whether remote-control warfare affects how we use violence. This essay will begin by exploring the concept of ‘virtual war’, showing that advances in military technology have served to reduce the risk of life in recent conflicts and interventions. It will be shown that spatial distance does not necessarily lead to callousness by exploring the civilian deaths in recent conflicts. Another theme of this paper will be how dehumanization creates an imagined distance between an aggressor and sufferer, making impunity more likely, using the abuse scandal at Abu Ghraib and the video game, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 as examples. Finally, this paper will assess the implications of distance on a spectator of violence, concluding that an imagined distance results in a perceived impotency and leads to indifference.

I will use Johan Galtung’s typology of violence – this encompasses ‘direct’ violence, ‘structural violence’ and ‘cultural violence’ – but all can be reduced down to a common denominator, that is, the unwanted and unnecessary impairment of human life to a standard below that of which is required to meet their needs. This could include anything from simple economic exploitation to injury and, ultimately, death (Galtung, 1996:197).

Recent NATO conflicts have become more technologically asymmetrical. As a result of this, Michael Ignatieff has presented the theory of “virtual war”: a reduced-risk warfare that uses technology to remove the aggressor from the situation (2001:162). A perfect example is Operation “Unified Protector”, the NATO intervention in Libya, which consisted of over 26,500 sorties, including 9,700 airstrikes, destroying over 5,900 military targets (NATO, 2011). Yet the only official casualty on the NATO side was a British airman who was killed in a car accident in Italy whilst on deployment. This seems to sum up Ignatieff’s contention with modern warfare; “technological mastery removed death from our experience of war. But war without death – to our side – is war that ceases to be fully real to us” (2001:4).

However, it seems that ‘virtual war’ may perhaps be the only means by which interventions can be conducted: a 2011 YouGov poll revealed that only 17% agreed to possibly sending armed troops to Libya even after the conflict had ‘ended’ (YouGov, 2011). Furthermore, UN Resolution 1973, which legally sanctioned the intervention, explicitly prohibited the deployment of NATO troops to Libyan soil. Although the nature of this intervention reduced the risk to NATO forces, they did not act with any degree of impunity – the Libyan military was specifically targeted and there was a relatively low amount of civilian deaths. In this situation, spatial distance reduces the risk to those intervening; with such technology at NATO’s disposal, it seems intangible not to employ such means. Bradley Strawser agrees, claiming that militaries are morally obliged to use Predator drones for the sole purpose of protecting their lives but only in the context of a justified conflict (2010:362). But what of civilian deaths – does this distance make them more likely?

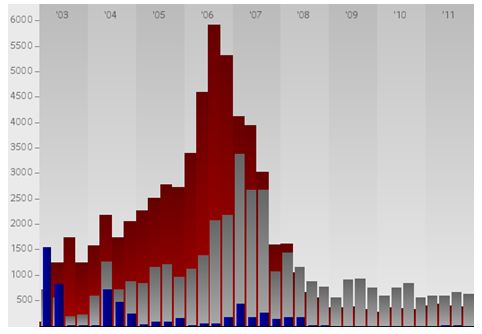

Virtual war has created the belief that war can be “clean” (Ignatieff, 2001:164). President Obama’s justification for using drones in the regions of Waziristan are based on such beliefs – in his Google+ ‘hangout’ he announced that “they [drone attacks] have been very precise, precision strikes against al-Qaeda and their affiliates” (BBC News, 31/01/2012). Interwoven into this language is the thought that warfare can be carried out with no consequences to civilians; a Human Rights Watch Report, Unacknowledged Deaths; Civilian Casualties in NATO’s Air Campaign in Libya, condemns the 72 civilian deaths that occurred as a result of NATO airstrikes. Furthermore, the Brookings Institute, despite conceding that drones are the US’s only option in North-western Pakistan, have revealed that such attacks have resulted in 10 civilians death for every targeted insurgent (Byman, 2009). Although these civilian deaths cannot be condoned, they seem to be consistent with civilian casualties in other conflicts: 79% of all casualties in the Iraq War (2003-2011) were civilians, and when viewing the methods of violence, we see that it is gunfire that caused the majority of civilian deaths (fig 1 – iraqbodycount.org, 2012). Thus it appears that distance does not necessarily lead to violence with impunity.

Furthermore, distinctions between civilian and combatant have become increasingly tedious in the current ‘War on Terror’. In September 2012, a suicide attack at Kabul International Airport was conducted by a 22 year old woman, and it is very possible that in other circumstances she would be regarded as a civilian. Indeed, Francois Debrix, building on Kristeva’s theory of abjection, claims that in the War on Terror there is no distinguishable enemy – the binary distinction of the ‘Other’ has been blurred by the tabloid press, creating an environment in which anybody could be implicated for terrorist activities (Debrix,2007:88). Inherent in these condemnations is the thought that this remote-controlled warfare seems to emotionally detach the aggressor from the situation and increase the likelihood of civilian deaths. How can we unravel this paradox, which combines the belief that these methods are more precise with the outspoken abhorrence towards civilian casualties? Carol Cohn (1985) informs us that the language surrounding contemporary warfare (for example words such as “precision” and “collateral damage”) serves to distort the realities of warfare. This, along with the reduced risk to drone pilots, distances the general public from the reality of war and creates a false narrative claiming that no civilians are killed. This is to the detriment of the armed forces – the controversy surrounding civilian deaths serves to reduce public support for the War on Terror.

Fig 1: Weapons claiming the most victims (civilians) in the Iraq War

Key: Red – Gunfire; Grey – Explosives; Blue – Air attacks

(source: http://www.iraqbodycount.org/analysis/numbers/2011/)

The distance involved with using Predator drones does not make their use unjustifiable. Scarry (1985:85) has concluded that warfare is a contest of pain, the champion being the one that has caused the most injury resulting in the submission of the enemy. Therefore argument against drones is akin to the ancient Greeks’ disdain for bows and arrows as embodied in Euripidies’ Hercules: “the measure of a man’s bravery is not archery; rather he who stands fast in his rank and gazes unflinchingly at the swift gash of the spear is the brave man” (Spence, 2002:59). There is a sense that the apparent lack of reciprocity created by this remote-controlled warfare is cowardly, immoral or unfair. Paul. W. Kahn asserts that warfare carries with it a mutual implication of risk. A result of this is that contemporary conflicts can no longer be viewed as legitimate warfare but as mere police enforcement (Kahn, 2002:5). John Keane, echoing Arendt, says violence is only permissible when it contributes to strengthening, or producing a peaceful civil society (1996:91). This implies that as long as the means sufficiently achieves this end, the type of violent means is morally justified. Alongside the military operation in Afghanistan, the NATO International Security Assistance Force has a division whose mission is to “engage with and develop civil society as a strategic partner in the long-term vision for stabilizing Afghanistan and fostering a healthy society” (ISAF). Through Keane’s framework, as long as UAV’s contribute to promoting civil society, their use is justifiable.

Violent video games are an example of how distance effects how we use and respond to violence. If we remember Ignatieff, he asserts that “technological mastery removed death from our experience of war” (2001:4). If we take the popular video game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 (MW3), has this not done just that? One can now sit in the comfort and protection of their own home and engage in full scale war, with all the trimmings, and the result will be enjoyment and a pronounced lack of death. The reason that the player can dispatch a vast multitude of unnamed enemies is because he believes that they are not really human (they are just bits of memory on a disc). Interestingly, 72% of Xbox owners approved of the CIA drone attacks in North-western Pakistan (Infowars.com, 2012), raising the question of whether this distance does indeed make us more accustomed to violence. However, the latest psychological study on violent video games has shown that “even engaging in harmless and gratuitous violence appears to be sufficient to make us feel we have lost elements of our own humanity” (Bastian, Jetten & Radke, 2012:490). Furthermore, a US Air Force study into post-traumatic stress disorder amongst drone pilots revealed that the pilots recorded exceptionally high levels of stress partly due to the fact that they are exposed to “hours of live video feed and images of destruction to ensure combatants have been effectively destroyed or neutralized” (Chappelle, Salinas & McDonald, 2012: 19-3). This may go some way to assessing the contention with UAV’s – if people who play these video games question their own humanity when using violence, then it is very likely that such emotions come into play when operating the drones. Thus it is very difficult, in light of this study, to argue that UAV pilots are more likely to act with impunity then those physically confronted with the enemy.

Moreover, Call of Duty has been produced for pleasure and for profit. Ergo, there must be an aspect of enjoyment in watching/ committing violence. Is it distance that enables us to enjoy violent video games? Edmund Burke did famously say that “terror is a passion which always produces delight when it does not press too close” (Bleiker, 2009:74). Theories of the ‘sublime’ explain where pleasure in violence comes from and, indeed, distance is an important precondition. We can define the sublime as a violent event that happens on such a large scale (e.g. 9/11) that it seems beyond the limits of comprehension; it inspires a plethora of feelings, from anger and hatred to relief and even pleasure (Bleiker, 2009:70). Violence of such magnitude, and the shock and awe it delivers, serve to reinforce the togetherness of the community that is affected (Debrix, 2007:130). It is this community-building, as well as the relief of not being killed, that the pleasure of violence comes from.

Sitting at home, watching the evening news reports of the faraway peoples of Waziristan protesting against CIA-controlled UAV’s, the average person may feel like this is not their battle. Sontag takes issue with this situation, observing that those who just see such images are ‘voyeurs’, and concluding that censorship of suffering should apply to all those except persons who could act to ease it (1985:37). Likewise, Kleinman and Kleinman highlight a contention with the production of violent images for financial profit, comparing it to the pornographic industry (1996:220). There is also a problem that constant exposure to violent images serve to desensitize our reactions to violence. On the contrary, photography and television are a means of raising awareness of violence where otherwise we would be ignorant and/ or indifferent. Ignatieff praises how television has enabled moral relations to be established between strangers: he argues that television in particular has not created indifference, but established a final lifeline of moral obligations that would otherwise not exist (1985:65). Despite this, both scholars advance that viewing violence and suffering endows the spectator with a moral obligation to act. But how can this average person act to prevent one of the most technologically capable militaries from operating in one of the most remote and inaccessible regions of the world? Luc Boltanski provides the circumstances in which this distant spectator of violence can overcome this apparent obstacle and fulfil their moral obligation. The novelty in Boltanski’s thought is located in accepting speech as a form of action – he claims that suffering will be overcome when there is an explicit (and impartial) commitment to action by the spectator (Boltanski, 1998:41).

Boltanski’s proposition has merit – raising awareness is always beneficial for any cause. As for action, charities can be seen as a bridge, or even better, a representative of the average person. Codepink, an American charity campaigning against the use of drones in Pakistan, embodies this commitment. It was present on Imran Kahn’s peace march to Waziristan, which was undertaken as a protest against the drone attacks in that area; committing oneself or donating money to a charity such as Codepink is a way of having one’s obligation to help recognized, which is an important aspect in Boltanski’s thought. Nevertheless, Ignatieff believes that donating money absolves the donor of all guilt and allows them to easily forget the cause (1985:62). But does this return us back to Sonatg’s original argument on exploitation? Donating money to certain charities is contemporarily viewed as an acceptable act, as a way of concurrently acting to relieve the sufferer from their pain and divesting the donator from all moral responsibility. This may be so, but for the majority of spectators, this may be the only opportunity to act. Donations are better than indifference. Returning to the language surrounding violence, Medea Benjamin, co-founder of Codepink, calls the attacks “barbarian assassinations”. Deconstructing this language reveals an important thought – the use of the word ‘barbarian’ is a method of reasoning why people use violence; in this instance, Benjamin dehumanizes the perpetrators, equating violence with sub-humanity.

Distance is integral to dehumanization and the violence that comes with it. Dehumanization is a result of the rejection from a community and the benefits it offers, primarily its social bonds and the entailing legal protections (Arendt, 1962: 297). The outsiders are distanced and thus reduced to “bare life”: exposed by the law and susceptible to a meaningless death (Agamben, 1998:28). A psychological study into dehumanization concluded that the presence of friends (in other words: a group) may make it easier for a person to rationalize their indifference with another which “can increase perceived distance between us and them” (my italics) (Waytz & Epley, 2012: 75). This helps to show that the creation and maintenance of groups, which involve establishing a social distance, are a precondition in dehumanizing others. Between 2004-5, over 14 members of the 320th Military Police Battalion were court-martialled for the abuse of detainees in Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq. The detainees’ dehumanized and ambiguous position is revealed by a US Department of Justice Memorandum of January 2002, which advanced that the rules of the Geneva Convention indeed did not apply to al-Qaeda and that the legal status of the Taliban militia could be demoted through the right to suspend treaty obligations (Bybee, 2002, 9-37). This is congruent with Samera Esmeir’s argument that humanity is conferred and also withdrawn by the law (2006:1544). Abu Ghraib prison fulfils all of Agamben’s criteria: military law prevailed over the camp (the perpetrators were tried under military law) and as can be seen in the photos, power confronted bare life (Agamben, 1998:171). Furthermore, Agamben claims that atrocities do not depend on law but on the cruelty or ethical sense of the police who temporarily act as sovereign (1998:174). The Taguba report, an inquest into the events at Abu Ghraib, illustrates such atrocities, particularly noting the use of phosphoric acid to burn detainees and the sodomising of detainees using broomsticks (Taguba, 2004:15). Slavoj Zizek says that our natural repulsion to witnessing torture is rooted in the Judaeo-Christian concept of “the neighbour” (Zizek, 2009:36). The pictures of humiliation (do not look if you are a strong supporter of Susan Sontag!) from Abu Ghraib reveal that the detainees have their heads covered, most probably to disorientate them and assist in their torture. However, these bags can be seen to dehumanize them, in order to make the administration of pain easier for the military police – Zizek points out that this concept of the neighbour implicates the detainees as a “person with a story to be told “ and not just a human body (2009:39). He draws on the thought of Emmanuel Levinas, who believes that “the face in all its nudity and defencelessness signifies ‘do not kill me’” (Bergo, 2011). In settings of proximity, when face-to-face with another human being, it is much more difficult to be violent towards them, whereas stripping them of their humanity creates a distance between the perpetrator and object where violence can be applied.

In conclusion, distance primarily serves to marginalize the risk of death to the aggressor. This is congruent in the cases of Predator drone pilots, the military police at Abu Ghraib and the video game player. However, it is a different aspect of distance that leads to unwarranted violence towards another – that is, the imagined distance caused by dehumanization. The psychological reduction of their victims allowed for the abuse at Abu Ghraib and for the countless deaths occurring in Call of Duty Modern Warfare 3. For the spectator, it has been revealed that distance ultimately produces indifference and inaction; an imagined connection is what overcomes this. Moreover, civilian deaths are a regrettable and almost unavoidable part of any conflict – whilst only practically reducing the risk of death to one’s own troops and general public, distance has carried along a narrative that warfare can extend such privileges to every non-combatant. This must not be confused with callousness that has increasingly become associated with the role that distance plays in violence.

Bibliography

Afghanistan International Security Assistance Force [ISAF] (n.d) ISAF Civil Society. [Online] Available at: www.isaf.nato.int/isaf-civil-society.html

Agamben, G. (1998). Homo Sacer. Stanford: University of California Press

Arendt, H. (1962) The Origins of Totalitarianism. London: Harcourt

Bastian, B., Jetten, J. & Radke, HRM.(2012) “Cyber-dehumanization: Violent video gameplay diminishes our humanity. Journal of Experimental Psychology 4(2) pp.486-491

BBC News (2012) Obama defends US drone strikes in Pakistan [Online] Last Updated 31 January 2012. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-16804247

Bergo, B. (2011) “Emmanuel Levinas”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , Edward N. Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2011/entries/levinas/

Bleiker, R. (2009). Aesthetics and World Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave

Boltanski, L. (1998). Distant Suffering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Bybee, J.S. (2002) Memorandum for Alberto R. Gonzales, Counsel to the President, and William J. Haynes II, General Counsel of the Department of Defense. Re: Application of Treaties and Laws to al Qaeda and Taliban Detainees, 22 January 2002. [Online] Available at: http://www.justice.gov/olc/docs/memo-laws-taliban-detainees.pdf

Byman, D.L. (2009) Do Targeted Killings Work?[Online] Brookings Institute. Last updated 14 July 2009. Available at: http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2009/07/14-targeted-killings-byman

Cohn, C. “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 12(4) pp.687-718

Chappele, W, Salinas, A & McDonald, S. (2012) Psychological Health Screening of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Operators and Supoorting Units. USAF School of Aerospace Medicine [Online] Available at: ftp.rta.nato.int/public//PubFullText/RTO/…///MP-HFM-205-19.doc

Debrix, F. (2007). Tabloid Terror. London: Routledge

Esmeir, Samera, 2006. “On Making Dehumanization Possible”. PMLA, 121(5), pp. 1544-51

Galtung, J. (1996) Peace by Peaceful Means. London: Sage

Human Rights Watch (2012) Unacknowledged Deaths: Civilian Casualties in NATO’s Air Campaign in Libya. [Report Online]. Available at: http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/libya0512_brochure_low.pdf

Ignatieff, M.(2001). Virtual War. London: Chatto and Windus

Ignatieff, M. (1985) “Is nothing sacred? The Ethics of Television” Daedalus 114(4) pp.57-78

Kahn, P.W. (2002) “The Paradox of Riskless Warfare” Faculty Scholarship Series Paper 326 http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1325&context=fss_papers

Keane. J. (1996) Reflections on Violence. London:Verso

Kleinman, A & Kleinman, J. (1996) “The Appeal of Experience, The Dismay of Images: Cultural Appropriations of Suffering in Our Times”, Daedalus, vol.125(1) pp.1-23

Melton, M. (2012) Conditoning? Xbox Poll Shows Overwhelming Gamer Support for “More Drone Strikes” [Online] Infowars.com Last Updated 24 October 2012. Available at http://www.infowars.com/xbox-live-poll-shows-overwhelming-support-for-more-drone-strikes/

McCormack, W. (2011) Targeted Killing at a Distane: Robotics and Self-Defense. Unpublished paper presented at Symposium on The Global Impact and Implementation of Human Rights Norms. March 2011. University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law [Online] Available at: http://www.mcgeorge.edu/Documents/Conferences/GlobeJune2012_TargetedKilling.pdf

NATO (2011) Operation Unified Protector: Final Mission Stats [Online] NATO. Last Updated 2 September 2011 Available at: http://www.nato.int/nato_static/assets/pdf/pdf_2011_11/20111108_111107-factsheet_up_factsfigures_en.pdf

Scarry, Elaine, 1985. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Singer. P.W/ TED (2009) P.W Singer on military robots and the future of war. [Video] Available at: http://www.ted.com/talks/pw_singer_on_robots_of_war.html

Sontag, S. (2003) Regarding the Pain of Others. London: Penguin

Spence, I.G (2002) Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Warfare. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

Strawser, B.J (2010): Moral Predators: The Duty to Employ Uninhabited Aerial Vehicles, Journal of Military Ethics, 9(4),pp. 342-368

Taguba, A. (2004) Taguba Report (Article 15-6 Investigation of the 800th Military Police Brigade) [Online] Available at http://www.npr.org/iraq/2004/prison_abuse_report.pdf

Waytz, A.& Epley, N. (2012) “Social connection enables dehumanization”. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48. pp.70-76

YouGov (2011) YouGov/ The Sun Survey Results [Online] 23 Aug 2011 Available at: http://cdn.yougov.com/today_uk_import/yg-archives-pol-sun-results-libya-230811.pdf

Zizek, S. (2009). Violence: Six Sideways Reflections. London: Profile Books.

[1] http://www.ted.com/talks/pw_singer_on_robots_of_war.html – a talk by Dr. P.W. Singer on how robots are changing the realities of war, drawing on themes from Ignatieff and Sontag.

—

Written by: Sebastian Booth

Written at: University of York

Written for: Audra Mitchell

Date written: January 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Use of “Remote” Warfare: A Strategy to Limit Loss and Responsibility

- ‘Drone Vision’: Precision Ethics Theory and the Royal Air Force’s use of Drones

- How Did Russia Use Anti-Western Narratives To Justify Intervening In Syria?

- Drones, Aid and Education: The Three Ways to Counter Terrorism

- ISIS’ Use of Sexual Violence as a Strategy of Terrorism in Iraq

- How Does the Italian Mafia Affect Mixed Migration?