What Have Been the Major Effects of Devolution on Politics in the UK? What Challenges Does It Pose for the State?

The United Kingdom has a unitary Constitution and is a multi-national state. Its institutions and powers have traditionally been highly centralized in the Westminster Parliament. Yet, the Labour Party, supported by the Liberal Democrats, introduced in 1997 and enacted in 1998 a fundamental change into this political model: devolution, i.e., the transference of powers from a central government to national governments. Devolution was intended to democratize the UK, to improve the territorial management and to unite its nations. Moreover, devolution should release a safety valve upon a pent-up nationalistic fervour. Yet the Conservatives remained resolutely against any threat to the UK integrity, seeing devolution as the thin end of a wedge which would ultimately fracture the Union altogether.

This essay examines the major effects of devolution on British politics and the challenges it poses for the State.

First, the essay explains that devolution created various government systems within the Union with varying degrees of power. Second, it describes the unequal electoral systems and the challenge of the UK becoming a multi-party system. This essay also analyses the unequal political and influence power, describing the imbalance in the constitutional system and the unequal distribution of the public budget. All these issues could have a ‘domino effect’ and end up in the creation of an English Parliament. Finally, this essay examines the main challenge: will devolution lead to the break up of the UK or to its consolidation?

Devolution targeted increased opportunities for democratic choice and popular participation in the government of local areas. Institutions, well informed about local needs, conditions and demands, were expected to guarantee a more responsive and rational decision-making system. This democratisation has been achieved, according to some experts: “What devolution did was to democratise this ‘state of unions’, transferring different sets of territorial competences formerly exercised from within central government to separate devolved governments established by new electoral processes” (Jeffery, C. 2008: 140). Yet others think that the transference of power has led to a disunited democracy: “The setting-up of the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Assembly mark the start of a new song. They seem to imply that the United Kingdom is becoming a union of nations, each with its own identity and institution, rather than (…) ‘one nation representing different kinds of people’” (Bogdanor, V. 1999: 287).

Complexity of the devolved political system has to be added to the costs of setting up transferred governments and providing them with a budget. In fact, devolution was asymmetric, introducing various layers of government systems within the Union and with heterogeneous degrees of power. While the Welsh Assembly was given a series of enumerated dominions and the power to scrutinize secondary legislation, the Scottish Parliament and the Northern Ireland Assembly were given primary legislative powers in matters not reserved to Westminster. Moreover, electoral systems in devolved governments mark a major innovation. In fact, the electoral system in Scotland and Wales – Additional Member System – achieve a closer correlation between the allocation of seats for parties in the Parliament and Assembly and their shares of the popular vote.

On the contrary, in the First Past the Post system (FPTP) used in Westminster, some parties (e.g. Liberal Democrats) are in clear disadvantage and, moreover, minority voices are almost not heard. Therefore, the Additional Member System advocates more equality among all parties threatening the FPTP: “It has enforced a more consensual governing style very different from the partisan, adversarial system that we saw embedded in the Westminster system” (Moran, M. 2005: 224).

This diversity of electoral systems could lead Great Britain to swap over from a two party system to a multiparty system. This shift, together with the newly decentralized aspect of the Westminster model, could lead to the Majoritarian democracy becoming a more consensus one.

“Devolution introduced imbalances into the constitutional system”, claimed Mr. Tam Dalyell, nowadays MP for Linlithgow. These imbalances led to still unresolved tensions and clashes between the devolved Parliaments and Westminster. A clear example is the ‘West Lothian Question’ which raises the following question: “Should Scottish MPs at Westminster be permitted to debate policy for England, while English MPs are excluded from the Scottish Parliament? Again, should Scotland maintain its existing over-representation at Westminster?” (Kingdom, J. 1999: 146). Even though 60% of English respondents to a 2003 survey were concerned about the ‘West Lothian Question’, the problem is still unresolved. “The West Lothian Question draws attention to a constitutional and political imbalance arising from asymmetrical devolution in an otherwise unitary state” (Bogdanor, V. 1999: 228).

In addition, there is an unequal distribution of public budget. The ‘Barnett Formula’ is often raised in association with the ‘West Lothian Question’ as ‘The English Question’. The ‘Barnett Formula’ is a mechanism used by the Treasury to adjust the amounts of public expenditure allocated to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. According to that formula, taxation and charges made in only one nation affect the other nations. As an example, tuition fees paid by English people are shared with Scottish universities, despite students in the latter universities not having to contribute any extra fees. English people criticise the ‘Barnett Formula’ because they argue that some regions benefit more than others. “Spending in policy areas that have been devolved to Scotland has been on average 31% per person higher in Scotland than in England” says the Campaign for an English Parliament (CEP 2011).

Another effect of devolution is that Scotland and Wales are over-represented in the House of Commons in comparison with England, which remains the ‘gaping hole’. Scotland and Wales have control over local government spending on devolved services and they have the right to establish their own expenditure priorities. Moreover, at least Scotland enjoys more public spending than those English regions whose GDP per head is lower. “The constitutional imbalance accentuated by devolution could lead to a serious economic imbalance favourable to Scotland and Wales, but unfavourable to the less privileged English regions” (Bogdanor, V 1999: 266). In addition, devolved governments have a better opportunity to defend their interests in the European Union.

Thus, English people are concerned about the constitutional differences. 75% of English respondents to a 2003 surveys were concerned that the Scottish Parliament did not raise enough of its own taxes (Devolution Survey 2003). Lacking representation in the Cabinet and lacking assemblies of their own, it is hard for England to influence the UK Parliament.

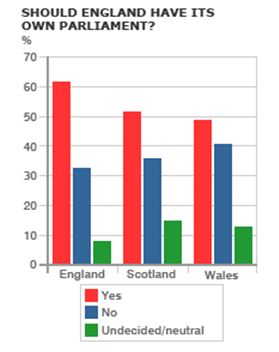

“Any devolution settlement has to be acceptable not just to the Scots and the Welsh but also to the English, who return 529 of the 659 Members of Parliament to Westminster and who constitute 85 per cent of the population of the United Kingdom” (Bogdanor, V. 1999:264). The above described lopsidedness could lead to a ‘domino effect’ in which the English look for fair play and equality of rights. For example, “in February 1998, the Conservative leader, William Hague, called for changes to be made in the government of England, following devolution to Scotland and Wales. He put forward as suggestions an English Grand Committee or an English parliament” (Bogdanor, V. 1999: 267). Mr. Tam Dalyell also concluded that, “some legislative entity is going to have to emerge in England to fill the vacuum left by Scottish home rule” (Turpin and Tomkins, 2007: 243). Nowadays many people, including those in Scotland, think that England should have its own parliament, as a BBC poll of 2007 found: “Newsnight found 61% in England, 51% in Scotland and 48% in Wales agreed with the idea”.

Source: BBC Article of 16 January 2007

Yet, some powerful politicians refuse this idea. Mr Cameron claimed in 2006: “The union between England, Scotland and Wales is good for us all and we are stronger together than we are apart. The last thing we need is yet another parliament with separate elections and more politicians spending more money” (Hennessy and Kite, 2006).

The main important challenge, however, is whether devolution will lead to the break up of the UK or to its consolidation. According to statistics from 2006, 59% of the English and 52% of the Scottish think that Scotland should become an independent country, and 48% of English people and 45% of Scottish believe that England should become independent of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (ibid).

Nationalist sentiments are spreading out, especially in Scotland, leading the UK to an unstable situation. The bad economic conditions are worsening even more the current circumstances. According to the austerity plan the UK presented in 2011: “between 2010-2011 and 2014-2015, the Scots will lose 6.8% of their grant, the Northern Irish 6.9% and the Welsh 7.5%” (Economist 2010). Alex Salmond, Scotland’s nationalist first minister, argues that, “now the pocket from Westminster is stingier, Scotland has even more reason to aim for independence and full control of its economy” (Ibid).

In the general elections of October 1974, the Scottish Nationalist Party used the British economic crisis to win 30% of the vote and 11 of Scotland’s 71 Westminster seats. Now under the same circumstances, the consequences for the British union could be even worse. A referendum on independence is going to take place in Scotland. The Scottish National Party wants the referendum to take place in the autumn of 2014, while the unionists want it ‘sooner rather than later’. Scottish nationalists are struggling in order to have an additional question in the referendum: whether Scotland should at least become Devo-Max, i.e. receive all powers except those of foreign and military affairs.

In summary, devolution represents the most important change that the Westminster model has ever experienced. Even though the principal objective was to consolidate the UK, devolution has affected its politics in many different ways and it challenges the UK’s integrity. John Major and Tom Nairn stated that devolution would lead to constitutional chaos and the disintegration of the UK. Others, such as ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair, predicted that devolution would be “the salvation of the UK” (Economist 2010). The central government in London will struggle in order to keep Great Britain united. Yet, the referendum on independence in Scotland may be the first step to the break up of the UK. The future remains uncertain.

Bibliography

Bogdanor, V. (2001). Devolution in the UK. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Budge, I., Crewe, I., McKay D., Newton K. (2004) The New British Politics. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited

Bulmer, S., Burch, M., Carter, C., Hogwood, P., Scott, A. (2002) British devolution and European policy-making. New York: Palgrave MacMillan

Campaign for an English Parliament (Accessed March 2011) ‘Barnett Formula’, http://www.thecep.org.uk/in-depth/the-“constitutional-case/the-barnett-formula/

Chisholm, M. (2000) Structural reform of British local government. Manchester: Manchester University Press

Dearlove, J., Saunders P. (2000) Introduction to British Politics. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers Ltd

Devolution and Constitutional Change Program Final Report (2006) Devolution, Public Attitudes and National Identity, accessed March 2011 at

http://www.devolution.ac.uk/Final%20Conf/Devolution%20public%20attitudes.pdf

Dunleavy, P., Gamble, A., Heffernan, R., Holliday I., Peele G. (2002) Developments in British Politics 6. New York: Palgrave MacMillan

Dunleavy, P., Heffernan, R., Cowley P., Hay, C. (2006) Developments in British Politics 8. New York: Palgrave MacMillan

Economist (2010) ‘The ties that bound: will the government’s spending cuts fray the union?’ 28 October 2010, available at: http://www.economist.com/node/17363770

Gamble, A. (2003) Between Europe and America: the Future of British Politics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Hennessey, P. and Kite, M. (2006) ‘Britain wants UK break up, poll shows’ Telegraph 26 November 2006, available at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1535193/Britain-wants-UK-break-up-poll-shows.html

Kingdom, J. (1999) Government and Politics in Britain, an Introduction. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers Ltd

Moran. M. (2005) Politics and Governance in the UK. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Turpin, C. (1999) British Government and the Constitution. London: Butterworths, a Division of Reed Elsevier (UK) Ltd

—

Written by: Alvaro Florez Diez

Written at: University of Sussex

Written for: Dr. Paul Webb

Date written: March 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Constructing a Narrative: Ontological Security in the Scottish Nation (State)

- Human Rights Law as a Control on the Exercise of Power in the UK

- Everyday (In)Security: An Autoethnography of Student Life in the UK

- Analysing the ‘Special Relationship’ between the US and UK in a Transatlantic Context

- Citizenship Deprivation Policy in the UK and Abroad: a Postcolonial Analysis

- Neoliberalism in the UK and New Zealand: Validating Ideational Analyses