Regional and International Organisations Can Have a Negative Impact on Conflict Resolution in Africa. Discuss.

‘I dream of an Africa which is in peace with itself’

(Mandela cited in Abdilahi 2012)

The magnitude of war in Africa is evident in the fact that, in the last decade, the attempt to deal with armed conflicts on the continent has made up about two-thirds of the United Nations Security Council’s activities and has involved nearly three quarters of its active peacekeepers (Williams: 2008: 309). International and regional organisations have often taken the lead in attempting to resolve these conflicts. ‘Conflict’ in Africa, since the end of the Cold War up to the present, has overwhelmingly been intrastate (Goulding: 1999: 157), coming in the form of the ‘new wars’ that Mary Kaldor has identified (Kaldor: 2001: 6). This distinction is important inasmuch as the nature of the conflicts determine specific difficulties in their resolution, with intrastate conflicts proving more difficult to resolve than war between states (Goulding: 1999: 157.)

To assess the impact of regional and international organisations on ‘conflict resolution’, it is necessary to define the term. Drawing from Ramsbotham (2009: 29) and Wallensteen (2002: 8), in this paper I define ‘conflict resolution’ as a comprehensive term that denotes a situation where belligerent parties (1) enter into a political agreement, which resolves the sources of their conflict and (2) cease all violent action against each other.

This paper will demonstrate the impact that the African Union (AU) and the United Nations (UN) had on the two conditions of conflict resolution outlined in my definition in Sudan, from 2003 to the present, with a focus on the Darfur crisis. The AU’s involvement in Sudan, as one of the first crises with which the organisation had volunteered to engage, is a “reflection of the effectiveness of the organization at large” (Birikorang: 2009: 6). Sudan also provides a contemporary look at the UN’s role in conflict resolution in Africa as the African Union/United Nations Hybrid operation in Darfur (UNAMID) is on-going.

The AU is an appropriate choice in that it is a pan-African regional organisation with near-universal membership and a Peace and Security Council established in 2003 which has as one of its functions the “resolution of conflicts” (Peace and Security Council 2012). It has unique legitimacy in conflict resolution in Africa in that its 2002 charter permits the AU to intervene militarily in its member states in the event of “war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity” (African Union: 2012).

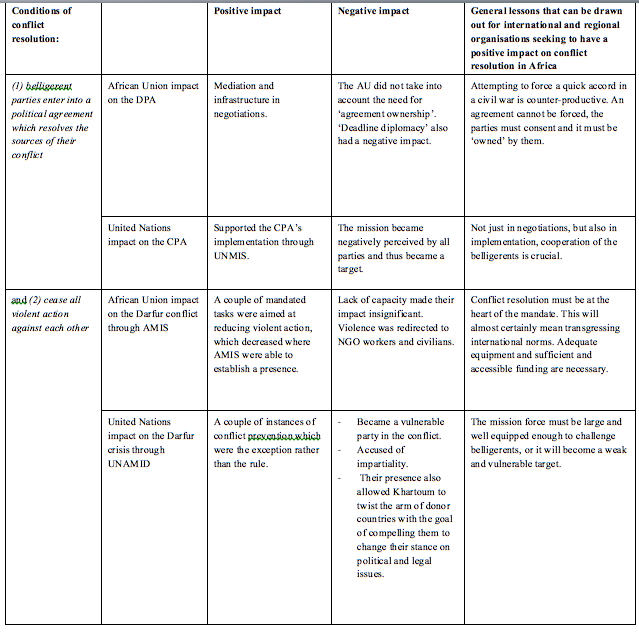

The UN provides an appropriate example as it has by far been the most significant single actor involved in conflict resolution in Africa (Williams: 2008: 316). From 1990 to 2008, the UN deployed to Africa twenty-four peacekeeping operations manned by a maximum of 144,375 personnel (Williams: 2008: 328). It has also accepted responsibility to end atrocities and mass killings, common in Africa, if the domestic government is unable or unwilling to protect its citizens through the responsibility to protect principle adopted in 2005 (Bellamy & Wheeler: 2008: 524) The paper will be split into two sections: the first, which will focus on the agreement aspect, will begin by unpacking the concept of a political agreement and demonstrating its necessity to ‘conflict resolution’. Following this, I will show that the AU had a positive impact on the Abuja Peace Talks, which led to the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) through the mediation and infrastructure it provided. This, however, was undermined by the negative impact it had by not ensuring that the parties saw the agreement as theirs (agreement ownership) and by the ‘deadline diplomacy’ approach they took to rushing through the talks. I will then show that the UN had a positive impact on the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) by supporting its implementation; however, this was impaired by the weak United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS), which became a target in the conflict. The second section, which focuses on the need for the cessation of violent action, will begin with a clarification of that aspect of the definition. Following this, I will assess the impact that the AU had on this second condition of conflict resolution in the Darfur crisis through the African Mission in Sudan (AMIS) by first looking at the mandate and then what happened on the ground. I will show that ‘conflict resolution’ was simply not on the mandate; although, it could have been if Article 4(h) had been invoked. I will then show that the AU through AMIS had a positive impact on the ground in the areas where it was able to establish a presence, but the mission was riddled with problems that limited this. Then, shifting the focus back to the UN, I will look at the impact it had through UNAMID. I will show that once again, conflict resolution was not on the mandate and as a result of this and other factors, the mission did not have a positive impact on the cessation of violent action on the ground. To end the paper, I will draw out universal lessons from these operations that apply to all regional and international organisations that seek to have a positive influence on conflict resolution in Africa. All findings are summarised in table 1 of the index.

Section 1 (a): Political Agreements

A principal element of conflict resolution is that belligerent parties must enter into a political agreement, which resolves the sources of their conflict. To clarify the term: an agreement of this kind is usually a formal settlement signed under solemn conditions; informal, implicit understandings between the parties may also occur (Wallensteen: 2002: 8). In order to establish that a political agreement is necessary for conflict resolution, it is important to first demonstrate that, according to the Clausewitzean view of conflict, war is merely an instrument of politics (Clausewitz: 1976: 255). Clausewitz argues that war can by no means exist alone, rather it is always joined to policy and policy is the dominant influence in the relationship between the two. Although it may appear that war indicates the abandonment of political interaction between actors, Clausewitz maintains the contrary, that war is a “continuation of political intercourse, with the addition of other means” (Clausewitz: 1976: 252). War does not, then, indicate the suspension of political intercourse or its transformation into something entirely different. This intercourse continues regardless of the means it employs (Clausewitz: 1976: 252). Clausewitz emphasises the unity between political motives and military action as inseparable, arguing that military events progress along political lines that extend throughout the conflict into the peace that follows (Clausewitz: 1976: 252).

This assessment of conflict as being controlled by political motives is as valid for the ‘new wars’ (Kaldor 2001) which, as I have noted, characterise conflict in Africa as it was for the inter-state wars that characterised conflict in Clausewitz’s time of writing. The ‘new wars’ of Africa are still motivated by political goals, but of a different nature. For example, Kaldor writes that these wars are motivated by “identity politics” which she defines as “the claim to power on the basis of a particular identity” (Kaldor: 2001: 7). Sheehan agrees that although war is a continuation of politics, it has become increasingly directed by issues of culture and identity (Sheehan: 2008: 222). Joxe has defended the enduring validity of the Clausewitzean view of the relationship between war and politics (Joxe: 2002: 165) and Duyvesteyn, in her Clausewitz and African War, demonstrates the continuing relevance of the Clausewitzean concepts for contemporary war in Africa (Duyvesteyn: 2005: 5).

The political agreement provides a next stage, following war, in the interaction between actors. Politics determines the “deep-rooted sources of conflict” (Ramsbotham: 2009: 29) and “central incompatibilities” (Wallensteen: 2002: 8) that lie beneath the surface of the conflict. Since war is politics conducted via different means, a political settlement is necessary to conflict resolution: if the political motives of the warring parties which lie beneath the surface of the conflict are satisfied, then the war which flows out of them will be extinguished.

Section 1(b): The Impact of the African Union and United Nations in Sudan

The AU

This necessity for a political agreement to be reached in order for a conflict to approach resolution holds true in the case of the Darfur crisis. De Waal and Mansaray agree that a political settlement between the government and rebel groups is the only viable route to peace in Darfur (de Waal: 2006: 739; Mansaray: 2009: 46). In this section, I will assess the impact that the African Union had on this aspect of conflict resolution by examining their role on the Abuja Peace Talks that began in 2004 that culminated in the signing of the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) in 2006.

The AU helped the warring parties to coalesce and come to a political settlement; it also had a positive impact on the Abuja talks themselves through the mediation and infrastructure that it provided. In terms of mediation, it did this by taking the initiative to have a strong and positive role in the Abuja Peace Talks conducted under its auspices (Barltrop: 2010: 4). For example, it entrenched its role by holding consultations with Government of Sudan (GoS) officials in Khartoum prior to the talks (Toga: 2007: 215) and attempted to steer the parties involved out of deadlock when it occurred (Toga: 2007: 227). In the second round of talks, it provision of a monitoring unit allowed the dialogue to move forward by offering verification of compliance (Toga: 2007: 222). In terms of infrastructure, the AU provided a drafting team to prepare the working documents required and a framework through which the talks would move forward through the Declaration of Principles (Toga: 2007: 225).

Despite the best efforts of the AU, however, the DPA did not achieve peace and in some ways aggravated the conflict. Neither party adhered to its commitments. As soon as September 2006, the GoS “bombed villages, attacked them with helicopter gunships, terrorized IDP [Internationally Displaced Person] camps, slaughtered women and children and rearmed and redeployed the Janjaweed [militia]”, while it formed a military alliance with Minnawi’s faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM), targeting the non-signatory faction of the SLM (Nathan: 2007: 220).

In certain respects, the AU had a negative impact on reaching a political agreement that would resolve sources of conflict. Firstly, since external mediators constructed the DPA, it was not owned by the Sudanese (de Waal: 2006: 737). This is a universal problem in attempts at conflict resolution by regional and international organisations; Wallensteen agrees that parties accepting the agreement as ‘theirs’ is crucial to its success (Wallensteen: 2002: 4). Secondly, what Nathan calls ‘deadline diplomacy’ was a major failure in the approach of the AU. Hopping from one monthly deadline to another, the AU tried to rush through negotiations as other external actors indicated that “the patience of the international community is running out” (Nathan: 2007: 247). Although the aim to produce a quick agreement was motivated by the grotesque level of death in Darfur, it had a negative impact on reaching an effective agreement.

A different approach however, may not have had better results. The main reason for the failure of the DPA was a lack of political will on the behalf of the belligerents to reach an agreement. De Waal for example, in his recount of the talks, claims that they pursued a strategy aimed at attaining short term tactical advantages, Khartoum “stonewalled on major issues” (de Waal: 2005: 132) and the various rebel factions were also unwilling (Mansaray: 2009: 40).

Although the AU’s positive contributions to reaching a comprehensive political settlement appear to be modest, it is important to ask what the situation in Darfur would have looked like had the AU not taken the initiative to hold, chair and mediate these talks. The role that the AU played in the Abuja talks salted the situation, preventing it from deteriorating at the rate that it would have done without them. There are however, two lessons to be learned that apply to all international and regional organisations attempting to have a positive impact on the reaching of a political agreement. The first is that attempting to force a quick accord in civil wars is counterproductive; even if the level of destruction is acute, mediators must be patient. The second is that an agreement cannot be forced on the parties. They must be willing and they must own it, so that it is not overwhelmingly externally constructed.

The UN

I will assess the impact that the United Nations had on my first condition of conflict resolution, concerning the reaching of a comprehensive political settlement, by looking at the impact they had on Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). In 1983, the Sudanese government attempted to install shari’a law in the country, marginalising the autonomy of the largely non-Arab south. This was followed by a brutal and complex civil war that persisted until the signing of the CPA, which officially ended the war in 2005 (van der Lijn: 2008: 7; Barltrop: 2010: 3-4).

The United Nations did have a positive impact on the CPA. However, the negotiations themselves did not rely on the UN for input or resources (Carney: 2007: 9). The UN supported the agreement’s implementation through the monitoring and verification roles of the United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS). The mission was authorized a maximum of 10,000 military personnel and an additional civilian component and was mandated to support the implementation of the CPA by Security Council Resolution 1590.

One element of the agreement that UNMIS was able to monitor and verify was the requirement of the Machakos Protocol that southern Sudan would have the right to vote in an “internationally monitored referendum either to confirm Sudan’s unity or vote for secession” (Simmons: 2006: 32). UNMIS not only monitored and verified the outcome of this referendum, but also provided technical and logistical support to its organisation, for example through determining the security conditions in which it was to take place (UNMIS 2011).

Another example of the positive impact of the UN is the implementation of the DPA through their monitoring of the troop redeployment agreed upon in the CPA. According to the agreement, the SPLM would redeploy the troops it had in the north of Sudan, while the GoS would redeploy the troops it had in the south (Brosche: 2008: 238). UNMIS was able to identify that the first deadline of 9 July 2007 for the GoS troops had not been met (Brosche: 2007: 2). Although the monitoring role of UNMIS had a positive impact and provided reliable third party authentication on the progress of the CPA’s implementation, we also see the limit of this role and the importance of the cooperation of the warring parties here as this deadline was missed “without any international reaction” (Brosche: 2007: 9).

The UN’s positive impact through UNMIS was in some ways marred. UNMIS got off to a bad start and its deployment lagged behind schedule (van der Lijn: 2008: 8). A more pressing problem that caused a negative impact on the implementation of the CPA was the repercussions of its involvement in the conflict in Darfur. An anti-United Nations campaign was kindled in Khartoum and other cities in response to UNMIS being outspoken about the killing in Darfur. This damaged its legitimacy and came to a head as UNMIS troops were deliberately targeted in the latter half of 2006 (van der Lijn: 2008: 9).Although UNMIS had a positive impact on the implementation of the CPA, this was heavily outweighed by the slow and selective cooperation by the GoS and rebels. This shows that, not just in negotiations (as with the DPA) but also in implementation, cooperation is crucial. In Sudan, UNMIS’s influence on implementation was especially limited by the strength and capacity of the government’s National Congress Party (NCP), which was “large compared to that of governments of countries in which peacekeeping operations are usually deployed” (van der Lijn: 2008: 10). Cooperation of the rebel groups was also limited (van der Lijn: 2008: 11), which hindered UNMIS. The lesson that can be drawn from this is that in the implementation of peace agreements, the belligerents must have the political will, and the larger and more powerful the actors involved, the less regional or international organisations will be able to have a positive impact without their consent.

Section 2: A Cessation of All Violent Action

The second crucial element of conflict resolution is that the warring parties must cease all violent action against each other. The necessity of this is quite self-evident and is the most important element. The first condition of ‘conflict resolution’ that requires the attainment of an effective political settlement would not be viable without it. It is safe to conclude then, as Wallensteen notes, for a conflict to be considered resolved, incompatibilities must be resolved by an agreement and the fighting must end (Wallensteen: 2002: 9).

In this section, I will determine the impact that the AU had on my second condition of conflict resolution in the Darfur crisis, by looking at the AMIS, the AU’s “first major peacekeeping experiment” (Udombana: 2007: 99). I will assess the impact that they were intended to have in theory by looking at their mandate and the impact that they had in practice by looking at what happened on the ground. Then I will assess the impact that the UN had on the Darfur crisis, through examining the combined UNAMID mission.

AMIS: Mandate

In order to situate my analysis of the AMIS mandate in context, a brief description of its formation is required. The mandate was agreed upon after drawn-out negotiations between the warring factions under the AU in 2004. The original mandate agreed upon in Addis Ababa in May 2004 was limited to monitoring the terms of the ceasefire agreed upon by the government and rebel groups in Darfur and protecting monitors and peacekeepers themselves (AU 2004). On October 20 2004, the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) enhanced the AMIS force and their mandate into AMIS II.

A few tasks on the mandate of AMIS II suggest that the AU was attempting to have a positive impact on conflict resolution by facilitating the cessation of violent action through the mission. For example, they were tasked to “monitor and verify the cessation all hostile acts by all parties”, and to “monitor and verify efforts by the Sudanese government to disarm government controlled militias” (Boshoff: 2005: 58). However, even the enlarged mandate was extremely restricted, with the main tasks being related to monitoring and verification. Ultimately, AMIS’s conflict resolution was not successful. This was to some extent due to external pressures, such as the GoS routinely voicing opposition to the expanded AMIS mandate on the basis that it violated their national sovereignty [Chang 2007: 16], which Mansaray suggests was a thinly veiled subterfuge given their proven character (Mansaray: 2009: 38).

Sector commander Seth Appiah-Mensah considered his mandate “severely restricted” (Mansaray: 2009: 38) and Lt. Eugene Ruzianda, who was stationed in El Fasher said of it “[e]very night you go to sleep thinking ‘I could do more.’ We could do more with a better mandate” (Wax 2004). The responsibility for this feeble mandate, which provided no room to contribute to the cessation of violent action, lies largely with the AU itself. A main cause of the weak mandate was the PSC’s position that Khartoum’s cooperation and consent were required (O’Neill and Cassis: 2005: 25). The AU had the authority, if it would have invoked Article 4(h) of its charter, to coerce Sudan into allowing AMIS greater freedom, which Mansaray argues could have slowed the activities of the warring parties (Mansaray 2009: 38), and would at least have been a step in the direction of reducing violent action. Instead, the PSC authorised a mandate so narrow and wooden that it became largely symbolic, where contributing to the cessation of violent action was not a mandated task.

AMIS: Practice

In terms of how the mission played out on the ground, AMIS was able to have a positive impact on the second dimension of conflict resolution. However, this positive impact was riddled with difficulties and limitations. They contributed to the cessation of violent action in the areas where they were able to establish a presence and episodes of violent action between the warring parties diminished, as did the number of attacks on civilians (Williams: 2006: 179). The trouble was, however, that these areas were few and far between. One of the main factors of AMIS’s limited impact was that it was “hopelessly small” in size (Williams: 2006: 168). In this respect, the AU limited the positive impact that they could have had on conflict resolution in Darfur by making the poor decision to put so few boots on the ground.

Commander Appiah-Mensah has opined that, beyond the mission being too thinly spread, efficiency and effectiveness were seriously hampered by inadequate equipment. AMIS was lacking “critical force enablers” (Appiah-Mensah: 2006: 11) such as vehicles and ICT equipment necessary to make the mission effective. Franke agrees that this deficiency in critical force enablers deeply limited AMIS (Franke: 2009: 259). This shortcoming in equipment had a direct effect on AMIS’s contribution to the cessation of violent action as they lacked the materiel to deter the government forces, Janjaweed militia or rebel groups. Mansaray reminds us that “[d]eterrent is a very important strategy in military warfare” (Mansaray: 2009: 42).

This lack of appropriate equipment reveals a related limitation on AMIS and the AU’s capacity for conflict resolution. The AU was unable to fund the mission. Funds were provided for a period of three months, after which the mission would look to another external source of financial good-will (Mansaray: 2009: 42), making planning beyond three months impossible. This restraint on AMIS’ ability to be a positive influence was exacerbated by the GoS who made what little funds they did have difficult to access (Mansaray: 2009: 38).

Although AMIS provided a positive influence on the cessation on violent action in some areas of Darfur, their ability to do this was severely limited by bad decision making in the PSC, a lack of political commitment and resources on the behalf of the AU as well as a flimsy mandate. When compounded with the antics of Khartoum and the rebel factions, which deliberately frustrated the impact of AMIS (Mansaray: 2009: 39-40), there was no real possibility that the mission would have a significant impact. Even the positive impact it did have came at a high cost, as although clashes between belligerents decreased, this violence was redirected at UN, NGO staff and civilians (S-2005-467: 2005: 17). AMIS exposed the limits of the AU as an authority of conflict resolution in Africa. A lesson that can be applied to all IOs and ROs seeking to have a positive influence on conflict resolution in Africa is that a purely symbolic intervention is futile; an appropriately large and properly equipped force with a robust mandate is required.

UNAMID: Mandate

In response to the weak and under-achieving AMIS, the United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) was established through Security Council Resolution 1769 on 31 July 2007. Whereas AMIS was authorised and mandated by the PSC, UNAMID was authorised and mandated by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). In this sense, it provides a good case for assessing the impact of the United Nations on conflict resolution, as the UNSC is the organ of the organisation most likely to have an impact on conflict resolution in Africa. The mission was conceived within the UN, with much of the background diplomacy being carried out by former Secretary General Kofi Annan. It is appropriate to examine a UN mission that is combined with an African regional organisation because as long as African governments cherish the principle of national sovereignty, the UN must work with African regional organisations in order to achieve any legitimacy and to avoid accusations of colonialism.

UNAMID was given a staggeringly broad mandate under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter with a dizzying 36 distinct tasks (UNAMID 2012) that threatened to overstretch the proposed force before there were even any boots on the ground (Jibril: 2010: 15). Many of the tasks themselves were huge undertakings to ‘monitor’, ‘contribute to’ and ‘assist’ in tasks such as civilian protection, the implementation of inclusive political systems, the promotion of the rule of law, the implementation of agreements and many other big tasks. Although some of these were relevant to contributing to conflict resolution promoting “efforts to disarm the Janjaweed and other militias” (UN 2011), ultimately, conflict resolution was once again not on the mandate.

A lesson that applies to all regional and international organisations that can be drawn from the formation of this mandate is that the interests of member states can compel them only to authorise a weak mandate. The permanent members of the Security Council who had a hand in forming the mandate were never likely to take strong action on Darfur because of vested interests in the Khartoum regime. For example, China had in the past 15 years invested $15 billion in Sudan and consumed 80% of its daily oil production (Fedyashin 2011). Along with Russia, it had in fact been selling Khartoum many of the arms they had used to engage in the conflict (Amnesty International: 2012: 7).

UNAMID: Practice

Overall, despite fractional improvements in the security situation (Jibril 2010: 24), the UNAMID mission did not have a positive impact on the second condition of conflict resolution. In contrast to contributing to the cessation of violent action between parties, UNAMID was sucked into being another party in the conflict, and a particularly weak one at that. Including members of non-military components, there were 132 fatalities within UNAMID since its deployment until September 2012 (UN 2012). This reflects the animosity felt for UNAMID from all sides of the conflict, which restricted their ability to positively affect conflict resolution. Expressions of disdain from stone-throwing to kidnapping and coldblooded killing have increased in number and frequency since UNAMID’s deployment, reflecting the belligerents’ as well as the civilians’ view that UNAMID presents an unwelcome interference rather than an element of conflict resolution (Jibril: 2010: 17). UNAMID have been repeatedly accused of impartiality, which has further damaged their credibility in the eyes of the warring parties (Sudantribune 2011).

The fact that UNAMID soldiers are acutely in need of protection themselves has a deeper negative impact on conflict resolution in Darfur. By sending a force so small and weak that it was unable to protect itself and was often attacked, with increasing evidence suggesting that the GoS is behind much of the hostility (Jibril 2010: 9), the UN provided a means through which the GoS could twist the arm of the international community. Jibril suggests that GoS has been sending “warning signals” by the killing and intimidation of soldiers. He also suggests that this was done with the strategic goal of compelling troop contributing countries to “change their position or soften their stands on legal and political issues confronting GoS such as the arrest warrants issued by the International Criminal Court against government officials… or to silence calls from such countries for a just and viable solution at the Darfur peace negotiations” (Jibril 2010: 17). President Bashir of the Khartoum government has also insisted that the renewal of UNAMID’s mandate be contingent on the withdrawal of International Criminal Court charges of genocide levelled against him (Tinsley 2009). The presence of UNAMID, then, did not draw the warring parties toward the cessation of violent action, rather it provided an opportunity for belligerents to entrench their position in the conflict and exert influence on troop donating countries.

Conclusion

To conclude, the AU and UN did have a positive impact on conflict resolution in the Darfur crisis in Sudan to a degree. However, this was reduced to being insignificant by external and internal limitations. Thus regional and international organisations can have a negative impact on conflict resolution in Africa. Nevertheless, there are lessons that can be drawn from their experience in Sudan that apply to all regional and international organisations that seek to have a positive impact on conflict resolution in Africa.

A point of failure for the AU was its attempt to rush the warring parties into signing an agreement through ‘deadline diplomacy’, which was counter-productive. Regional and international organisations must be patient in mediation. For instance, negotiations to reach a peace settlement took over two years in Mozambique and four years in South Africa (Toga 2007: 249). Another valuable lesson is that an agreement cannot be forced on parties. They must be willing and they must own it so that it is not overly externally constructed. In the UN’s attempt to support the implementation of the CPA, which was heavily outweighed by the slow and selective implementation of the GoS and rebels, we learn that not just in negotiations, but also in implementation, cooperation is crucial.

Through AMIS’s experiences, we learn that, in order for a peace-keeping operation to have a positive impact on conflict resolution, it must have a mandate with that task at the centre. At the time of writing, this will almost certainly mean transgressing norms of international behaviour. In terms of what we can learn of how the AMIS mission played out in reality, regional and international missions must have adequate equipment, a strong mandate, and stable, reliable, accessible and sufficient funds in order to have a chance at positively influencing conflict resolution in Africa. Examining UNAMID’s mandate reinforces the lesson that conflict resolution must be included; yet the interests of member states may interfere with mandate formation. From how the mission played out in reality, regional and international organisations can learn that a force must be large enough and well equipped enough to challenge the belligerents or it will become a weak and vulnerable target.

Index

Bibliography

AMIS I mandate: AU (2004) AU Communique, PSC/PR/Comm. (XVII)

African Union (2012) ‘The Constitutive Act’ (http://www.africa-union.org/root/au/aboutau/constitutive_act_en.htm#Article4) Accessed 14/12/2012 12:18

M. Abdilahi (2012) I dream of an Africa which is in peace with itself (http://somalilandpress.com/i-dream-of-an-africa-which-is-in-peace-with-itself-n%E2%80%8Belson-mandela-26765) Accessed 14/12/2012 00:16

Amnesty International (2012) Sudan: No End to Violence in Darfur: Arms Supplies Continue Despite Ongoing Human Rights Violations, International Secretariat, London.

S. Appiah-Mensah (2006) ‘The African Mission in Sudan: Darfur dilemmas’, African Security Review, Vol 15, No. 1. pp. 2-19

R. Barltrop (2010) Darfur and the International Community: The Challenges of Conflict Resolution in Sudan, London, I.B Tauris

A. Bellamy and N. Wheeler (2008)’Humanitarian intervention in world politics’, in J. Baylis (ed.) The Globalization of World Politics 4th ed. USA, Oxford University Press, pp. 510-528

E. Birikorang (2009) Towards Attaining Peace in Darfur: Challenges to a Successful AU/UN Hybrid Mission in Darfur, KAIPTC Occasional Paper No. 25.

J. Brosche (2007) ‘CPA New Sudan, Old Sudan or Two Sudans?’ Journal of African Policy Studies Vol. 13, No. 1. pp. 26-61

H. Boshoff (2006) ‘The African Mission in Sudan’, African Security Review, Vol. 14, pp. 57-60.

T. Carney (2007). Some assembly required: Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement, Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace.

T. Chang (2007) ‘An analysis of humanitarian and protection operations for the internally displaced in Darfur’, KAIPTC paper, no. 18

C. Clausewitz (1976) On War, Princeton : Princeton University Press

I. Duyvesteyn (2005), Clausewitz And African War: Politics And Strategy In Liberia And Somalia, Abbingdon, Taylor and Francis.

A. Fawole (2004), ‘A Continent in Crisis’, African Affairs, 103, pp. 297-303

A. Fedyashin (2011) ‘Sudan’s impending split’ (http://en.rian.ru/analysis/20110109/162045034.html) Accessed 13/12/2012 23:04

B. Franke (2009) ‘Support to AMIS and AMISON (Sudan and Somalia), in G. Grevi (ed.) European Security and Defence Policy: the first ten years (1999-2009), Paris, The European Union Institute for Security Studies.

M. Goulding (1999), ‘The United Nations and Conflict in Africa since the Cold War’, African Affairs, Vol. 98, No. 391 , pp. 155-166.

A. Jibril (2010) Human Rights and Advocacy Network for Democracy, Past and Future of UNAMID: Tragic Failure or Glorious Success? Darfur Relief and Documentation Centre, Geneva (Switzerland)

A. Joxe, (2002), Empire of Disorder, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e).

M. Kaldor (2001), New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era, Oxford, Blackwell Publishers.

van der Lijn (2008) To paint the Nile blue: factors for success and failure of UNMIS and UNAMID. Den Haag: Clingendael Conflict Research Unit

A. Mansaray (2009) ‘AMIS in Darfur: Africa’s litmus test in peacekeeping and mediation’, African Security Review, Vol. 18, No. 1. pp. 36-48

L. Nathan (2007) ‘The Making and Unmaking of the Darfur Peace Agreement’, in A. de Waal (ed.) War in Darfur and the Search for Peace, pp. 245-267.

W. O’Neill & V Cassis (2005) Protecting Two Million Internally Displaced: The Successes and Shortcomings of the African Union in Darfur, The Brookings Institution—University of Bern Project on Internal Displacement.

Udombana (2007), ‘Still Playing Dice with Lives: Darfur and Security Council Resolution 1706’, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 97 – 116

Peace and Security Council (2012) ‘The Peace and Security Department (PSD)’ (http://128.121.86.38/~au/en/dp/ps/psd?q=psd) Accessed 14/12/2012 12:21

UNAMID (2012) mandate (http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unamid/mandate.shtml) Accessed 13/12/2012 20:57

UN (2005) S/RES/1590, Monthly report of the Secretary-General on Darfur, New York, United Nations.

UN (2012) UNAMID Facts and Figures (http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unamid/facts.shtml) 13/12/2012 Accessed 23:09

(http://unmis.unmissions.org/Default.aspx?tabid=511&ctl=Details&mid=697&ItemID=11313) Accessed 13/12/2012 22:58

O. Ramsbotham, T. Woodhouse, Hugh Miall (2009) Contemporary Conflict Resolution: The prevention, management and transformation of deadly conflicts, Cambridge, Polity Press.

M. Simmons and P. Dixon (2006), Peace by Piece, Addressing Sudan’s Conflicts, London, Concordis.

M. Sheehan, M. (2008) ‘The Changing Character of War’ in J. Baylis (ed.) The Globalization of World Politics 4th ed. USA, Oxford University Press .pp 214-230

Sudan Tribune (2011) ‘SLM rebels say UNAMID chief is “no longer a neutral and valid interlocutor’ (http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article40198) Accessed 14/12/2012 12:11

R. Tinsley (2009) ‘The Failure of Unamid’ (http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/jan/01/darfur) Accessed 14/12/2012 11:58

D. Toga (2007), ‘The African Union Mediation and the Abuja Peace Talks’, in A. de Waal (ed.) War in Darfur and the Search for Peace, pp. 214-245.

A. de Waal (2005) ‘Briefing: Darfur, Sudan: Prospects for Peace’, African Affairs, Vol. 104, pp. 127-135.

A. de Waal (2006), ‘Darfur!’, Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 33, No. 110, pp. 737-739.

P. Wallensteen (2002) Understanding Conflict Resolution: War, Peace and the Global System, London, Sage.

P. Williams (2006) ‘The African Union: Prospects for Regional Peacekeeping after Burundi and Sudan’, Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 33, No. 108, pp. 352-357

P. Williams (2008) ‘Keeping the Peace in Africa: Why “African” Solutions Are Not Enough’, Ethics and International Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 3. pp. 309-323

Wax (2004) ‘In Darfur, Rwandan Soldiers Relive Their Past’ (http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A55184-2004Sep27.html)

—

Written by: Anthony Demetriou

Written at: The University of Nottingham

Written for: Catherine Gegout

Date written: December 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam: Cooperation and Conflict Resolution

- Security Council Resolution 1325’s Impact on Kosovo’s Post-Conflict Framework

- A New Era of UN Peacekeeping? The Women, Peace and Security Agenda in Africa

- To What Extent Has China’s Security Policy Evolved in Sub-saharan Africa?

- China in Africa: A Form of Neo-Colonialism?

- A Peaceful Resolution: Analysing Sustained Peace and Order in Mizoram