The ramping up of violent attacks on diverse civilian and military targets in Nigeria by Boko Haram (BH) since July 2009, when it launched a short-lived anti-government revolt, has effectively made the group a subject of interest to states, security agencies, journalists and scholars. The revolt ended when its charismatic leader, Mohammed Yusuf, was finally captured and later brutally murdered by the police. Following the death of Yusuf and the mass killings and arrest of many of their members, the sect retreated and re-strategised in two ways. First was the adoption of Yusuf’s hard-line deputy, Abubakar Shekau, alias ‘Darul Tawheed’, as its new spiritual leader. Second was the redefinition of its tactics, which involved perfecting its traditional hit-and-run tactics and adding new flexible violent tactics, such as the placement of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), targeted assassination, drive-by shooting and suicide bombings.[i]

Its attacks had traditionally focused on the security establishment and personnel, community and religious leaders, politicians, centres of worship, and other civilian targets. Over time, it has added markets, public schools, hospitals, tertiary institutions, media houses, and more recently, critical infrastructure such as telecommunication facilities to the list of its ruthless attacks. While the scale and impact of its attacks have earned BH intense local and international media coverage, neither the tactics employed nor its evolving targets suggests anything hitherto unknown to the history of jihadist and terrorist violence.

Focusing on its attacks on telecommunication infrastructure in Nigeria, this piece draws from the Taliban case in Afghanistan to demonstrate that emerging jihadist groups tend to copy tactics or strategies adopted by older terrorist groups in dealing with any problem or achieving their strategic objectives. Effort will be made to highlight the costs of such attacks, as well as proffer recommendations for the protection of such critical infrastructure. Before proceeding to addressing these issues, it is pertinent to begin with an understanding of the sect.

Understanding Boko Haram

Most media, writers and commentators date the origin of BH to 2002. However, security operatives in Nigeria trace its true historical root to 1995, when Abubakar Lawan established the Ahlulsunna wal’jama’ah hijra or Shabaab group (Muslim Youth Organisation) in Maduigiri, Borno State. It flourished as a non-violent movement until Mohammed Yusuf assumed leadership of the sect in 2002. Over time, the group has metamorphosed under various names like the Nigerian Taliban, Muhajirun, Yusufiyyah sect, and BH. The sect, however, prefers to be addressed as the Jama’atu Ahlissunnah Lidda’awati wal Jihad, meaning a ‘People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad’.

BH considers western influence on Islamic society, particularly western education, as the basis of the religion’s weakness. Its ideology is rooted in Salafi jihadism, and driven by Takfirism. Salafism, for instance, seeks to purge Islam of outside influences and strives for a return to the Islam practiced by the ‘pious ancestors’, that is, Muhammad and the early Islamic community. Salafist Jihadism is one specific interpretation of Salafism which extols the use of violence to bring about such radical change.[ii] Adding to the Salafi Jihadi ideological strain is Takfirism. At the core of Takfirism is the Arabic word takfir—pronouncing an action or an individual un-Islamic.[iii] Takfirism classifies all non-practising Muslims as kafirs (infidels) and calls upon its adherents to abandon existing Muslim societies, settle in isolated communities and fight all Muslim infidels.[iv] BH adherents are motivated by the conviction that the Nigerian state is a cesspit of social vices, thus ‘the best thing for a devout Muslim to do was to ‘migrate’ from the morally bankrupt society to a secluded place and establish an ideal Islamic society devoid of political corruption and moral deprivation’.[v] Non-members were therefore considered as kuffar (disbelievers; those who deny the truth) or fasiqun (wrong-doers), making such individual or group a legitimate target of attack by the sect. Its ideological mission is to overthrow the secular Nigerian state and impose its own interpretation of Islamic Sharia law in the country.

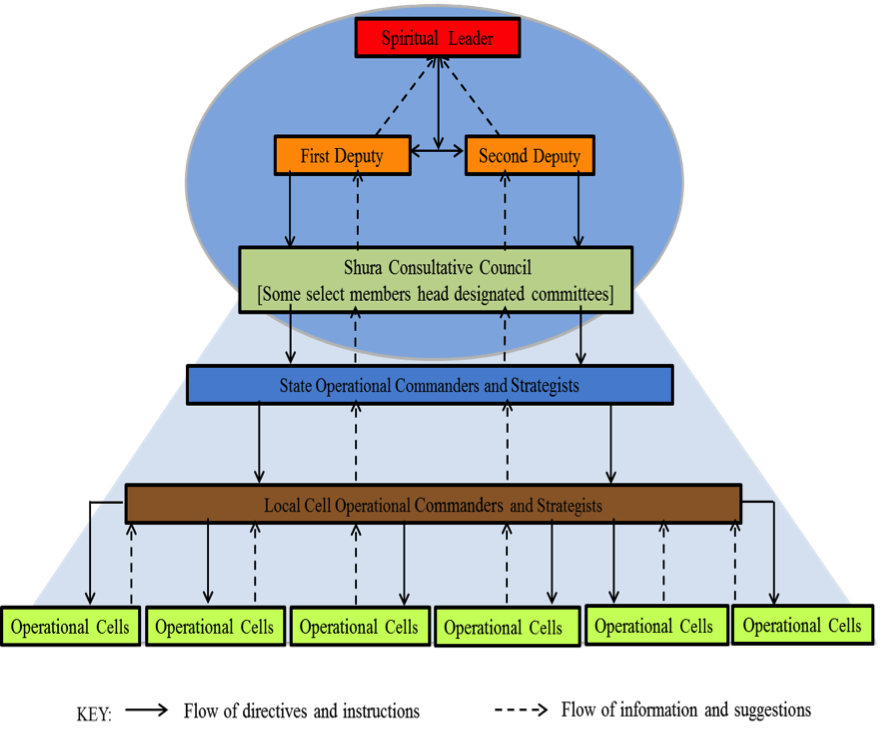

BH was led by Ustaz Mohammed Yusuf until his death just after the July 2009 uprising. Before his death, Muhammad Yusuf was the Commander in Chief (Amir ul-Aam) or leader of the sect, and had two deputies (Na’ib Amir ul-Aam I & II). Each state where they existed had its own Amir (commander/leader), and each local government area where they operated also had an Amir. They also organised themselves according to various roles, such as soldiers and police, among others.[vi] In the aftermath of Yusuf’s death, one of his deputies, Abubakar Shekau, became the new spiritual leader of the sect. Abubakar Shekau inherited, if not modified, the organisational structure of the sect (figure 1). Under Shekau, the sect maintains a loose command-and-control structure, which allows it to operate autonomously. It now operates in some sort of cells and units that are interlinked, but generally, they take directives from one commander.[vii] Abubakar Shekau heads the Shura Consultative Council that has authorised the increasingly sophisticated attacks by various cells of the sect since the July 2009 revolt.

Figure1: Hypothetical Organisational Structure of the BH under Abubakar Shekau[viii]

Figure1: Hypothetical Organisational Structure of the BH under Abubakar Shekau[viii]

At its early stage, the sect was entrenched in Borno, Yobe, Katsina, and Bauchi states. Over time it has recruited more followers and established operating cells in almost all northern states, probably nursing the intention to spread further South. The majority of its foot soldiers are drawn from disaffected youths, unemployed graduates and former Almajiris. Wealthy Nigerians are known to provide financial and other forms of support to the sect.

BH finances its activities through several means: payment of membership dues; donations from politicians and government officials; financial support from other terrorist groups – Al Qaida; and organised crime, especially bank robbery. Analysts have posited that the sect may turn to other criminal activities such as kidnapping, trafficking in SALWs and narcotics, and offering protection rackets for criminal networks to raise funds.[ix]

Boko Haram: A History of Violence

The sect resorting to violence in pursuit of its objective dates back to 24 December 2003 when it attacked police stations and public buildings in the towns of Geiam and Kanamma in Yobe State. It was then known in the media as the ‘Nigerian Taliban’. In 2004 it established a base called ‘Afghanistan’ in Kanamma village in northern Yobe State. On 21 September 2004 members attacked Bama and Gworza police stations in Borno State, killing several policemen and stealing arms and ammunition. It maintained intermittent hit-and-run attacks on security posts in some parts of Borno and Yobe States until July 2009, when it staged a major anti-government revolt, in revenge for the killing of its members by state security forces. The fighting lasted from 26 to 30 July 2009, across five northern states: Bauchi, Borno, Kano, Katsina, and Yobe. The revolt ended when its leader, Mohammed Yusuf, was finally captured by the military and handed over to police. Yusuf was extrajudicially murdered in police custody, although police officials claimed that he was killed while trying to escape. Several other arrested members were also summarily executed by the police.

Since the July 2009 revolt, the sect has evolved into a more dynamic and decentralised organisation, capable of changing tactics as well as expanding or reordering target selection. A conservative estimate of over 3,000 people have been killed by the sect since 2009, aside from damage to private and public property. Critical infrastructure such as telecommunication facilities forms part of BH’s expanding targets of attacks.

Cell Wars: Terror Attacks on Telecom Facilities

Recent confrontations between state security forces and insurgents or terrorists in countries such as Afghanistan, India, and Iraq have shown how critical telecommunication infrastructure can easily become both a target of, and battle ground, for the actors in conflict. Analysts have dubbed this reality ‘cell wars’. The experience of Afghanistan offers a perfect precedent for underscoring the Nigerian experience vis-à-vis BH attack on telecom facilities.

Mobile phones were introduced in Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban in 2001. It has since then become the principal means of communication and one of Afghanistan’s fastest-growing and most profitable sectors. Even the Taliban that once shunned using mobile phones later found itself increasingly relying on this instrument of modernity to communicate and coordinate their operations, spread propaganda, and to activate IEDs.

Attack on telecom facilities in Afghanistan dates back to 2007 when the Taliban began attacking transmission masts (resulting in limited damage) to extort money from telecom companies.[x] From 2008, the purpose of attack became different (strategic) and the frequency and extent of damage more severe. In the first of such attack, the Taliban on 1 February 2008 destroyed a tower along the main highway in the Zhari district of Kandahar province, which belongs to Areeba, one of Afghanistan’s four mobile phone companies.

On 25 February 2008, a Taliban spokesman, Zabiullah Mujaheed, threatened that militants will blow up further towers across Afghanistan if the companies did not switch off their signals at night for 10 hours. According to him, the Taliban have ‘decided to give a three-day deadline to all mobile phone companies to stop their signals from 5 p.m. to 3 a.m. in order to stop the enemies from getting intelligence through mobile phones’.[xi] It was believed that the US and NATO Special Forces’ night-time decapitation and capture operations against the Taliban relied substantially on intelligence gleaned from tipoffs and phone intercepts. To be sure, the US forces had killed more than 50 mid- and top-level Taliban leaders, by conducting specific military raids at night.

Telecom operators initially did not heed the order. In retribution, the Taliban started mounting crippling attacks on the network of transmission masts. Attacks soared, with an estimated 30 towers being destroyed or damaged in one 20-day period. Towers owned by companies such as the Afghan Wireless Communication Company, Areeba, and Roshan, were hit by militants in Helmand, Herat, Jawzjan, Kandahar, Logar, and Zabul provinces. Under pressure from these attacks, the major carriers began turning off their signals.

Despite US pressure and a decree by President Hamid Karzai ordering phone companies to defy insurgent demands, telecom operators resisted complying completely, fearing even more attacks on their facilities, offices and staff. The targeting of cell towers by the Taliban was both strategic and symbolic. The strategic objective of the Taliban was to deny US, NATO and Afghan forces of information or intelligence that would aid the capturing or killing of its members. In symbolic terms, it signifies the capacity of insurgents to hit targets listed as ‘enemies’. Tactics like the cellphone offensive have allowed the Taliban to project their presence in far more insidious and sophisticated ways. By forcing a night-time communications blackout, the Taliban sends a daily reminder to hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Afghans that they still hold substantial sway over their future.[xii]

Faced with a similar situation in Nigeria, BH pulled a similar stunt. By way of brief background, the Global System of Mobile communication (GSM) was introduced in Nigeria in August 2001. Before then, only about 500,000 telephone lines were provided by the national telecoms monopoly (NITEL) in a country of about 120 million people.[xiii] Given the liberalisation of the telecoms sector and coupled with a favourable regulatory regime, the telecom sector in Nigeria continues to witness significant growth in both investments and mobile subscriptions. While local and foreign direct investment in the sector stood at $25bn in mid-2012, mobile subscriptions have surpassed over 150 million; 113.1 million of which were active at the end of December 2012.[xiv] The sector has proven to be the live wire of the Nigerian economy, facilitating cross-industry linkages, efficiency and productivity across the economy and providing the platform for the fledging banking sector.

The proliferation of Base Transceiver Stations (BTS), also known as base stations, telecom masts or cell towers, is one of the visible features of the rapid growth of the sector. These base stations facilitate effective wireless communication between user apparatuses, for instance, mobile phones and networks. A breakdown of the 20,000 base stations across Nigeria shows that MTN owns 7,000; Globacom, 5000; Airtel, 4000; and Etisalat, 2,000. The Code-Division Multiple Access (CDMA) operators accounted for 2000 masts.[xv]

The traditional threats to the integrity of telecom facilities such as base stations, generators, and fiber cables have been vandalism, with the intent of stealing valuable parts, accidental damage due to road construction and maintenance work, and natural disasters such as flooding. However, targeted attacks on this critical infrastructure by members of BH is now a major threat to the operation of the sector.

In July 2011, President Goodluck Jonathan revealed his administration’s plans under the purview of the National Security Adviser (NSA) to make telecommunications operators dedicate emergency toll-free lines to the public to fast-track its intelligence gathering on the sect.[xvi] On 14 February 2012, a BH spokesman, Abul ‘Qaqa’, threatened that the group will attack GSM service providers and Nigeria Communication Commission (NCC) offices for their alleged role in the arrest of their members. As he puts it: ‘we have realised that the mobile phone operators and the NCC have been assisting security agencies in tracking and arresting our members by bugging their lines and enabling the security agents to locate the position of our members’.[xvii]

The sect made good its threat on September 2012, when it launched a two-day coordinated attack on telecom masts belonging to several telecom operators across five cities in northern Nigeria: Bauchi, Gombe, Maiduguri, Kano, and Potiskum. A statement purportedly issued by the BH spokesman, Abul Qaqa, admitted responsibility for the bombing of telecommunication facilities, claiming that they launched ‘the attacks on masts of mobile telecom operators as a result of the assistance they offer security agents’. BH has mounted several such attacks, mostly targeting base stations. Attacks on telecom facilities add a new dimension to the pre-existing security challenges, as entire base stations are destroyed with IEDs, suicide bombers and other incendiary devices.

Overall in 2012, some 530 base stations were damaged in Nigeria. While 380 were destroyed by floods that affected many communities in many states of the federation, 150 were damaged in northern Nigeria by BH.[xviii] Like the Taliban in Afghanistan, the strategic objective of BH attacks on telecom infrastructure is to choke one of the supply lines of intelligence to Nigeria’s intelligence and security system. However, when terrorists or insurgents successfully attack critical telecommunication infrastructure, it generates costs that could be assessed from different angles depending on the nature and criticality of such a facility to the economy and security. The BH attacks on base stations have generated at least three dimensions of ‘costs’, namely:

Casualty Cost

Damage in the form of death, bodily injuries and trauma are obvious consequences of violent terrorist acts. In the BH case, both fixed assets and staff of such telecom providers are legitimate targets of attacks. Therefore, the death of any member of a family from such attacks leads to a deep fracturing of kinship structures. Some children have been left without parents, husbands without wives, and vice versa. Hence, for every person killed or injured, there are many more who must cope with the psychological, physical and economic effects that endure in its aftermath.

Service Cost

Attacks on telecom infrastructure obviously leads to network outages and poor services delivery, which manifest in the form of increased dropped call rates, poor connections and lack of voice clarity. Apart from voice calls, data services are also impaired such that the use of modems to browse the internet will not be effective. This disruptive effect cascades through the entire national system (such as banking services) that rely on voice calls and data services provided by the telecom sector.

Financial Cost

Another cost is that network operators will spend money initially earmarked for network expansion and optimising existing infrastructure on replacing the damaged facilities. Telecom operators in Nigeria have lost about

N75bn (naira) to damage caused by BH and flooding in 2012. Telecoms infrastructure analysts have put the average cost of a base station in Nigeria at $250,000 (N 39.47 million), and it will cost some N15.9 billion to replace the damaged base stations.

Conclusion

The foregoing analysis shows that terrorist groups follow a ‘learning and responding curve’ to deal with similar challengers or situations. The targeting of telecom infrastructure by BH in Nigeria followed the same strategic trajectory as the Taliban in Afghanistan. With several telecom facilities scattered in isolated places in Nigeria, BH can always attack and destroy them at ease. However, the position such facilities will occupy in the priority list of targets will definitely depend on the extent to which BH judges the telecom operators as undermining their security. Therefore, the persistent damage to telecom infrastructure as a result of terror attacks calls for a more robust mechanism to safeguard the integrity of this sector which is critical to the economy and security. To better protect critical infrastructure more generally, and telecom facilities in particular, the Nigerian government in partnership with relevant stakeholders needs to adopt the following steps: a) carry out a Telecom Infrastructure Vulnerability and Risk Assessment (TIVRA) of the sector with a view to designating such facilities as critical infrastructure and key resources (CI/KR); b) develop a robust Telecom Infrastructure Protection Plan (TIPP), based on the findings from the TIVRA; c) activate coherent, preventive, responsive and offensive measures informed by the TIPP, for protecting these facilities; and d) integrate the entire effort into a broad national counter terrorism strategy.

—

Freedom C Onuoha is a fellow at the Centre For Strategic Research And Studies, National Defence College, Nigeria. This article is part of e-IR’s Edited Collection ‘Boko Haram: The Anatomy of a Crisis’.

[i] F. C Onuoha, ‘(Un)Willing to Die: Boko Haram and Suicide Terrorism in Nigeria’, Report, Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, 24 December 2012, p.1.

[ii] European Commission’s Expert Group on Violent Radicalisation, “Radicalisation Processes Leading to Acts of Terrorism”, A Concise Report submitted to the European Commission, 15 May 2008, p. 6.

[iii] H. Mneimneh, ‘Takfirism’, Critical Threats, 1 October 2009, http://www.criticalthreats.org/al-qaeda/basics/takfirism

[iv] S. S Shahzad, “Takfirism: A Messianic Ideology”, Le Monde diplomatique, 3 July 2007, http://mondediplo.com/2007/07/03takfirism

[v] O Akanji, The politics of combating domestic terrorism in Nigeria. In: W Okumu, and A. Botha, (eds.), Domestic terrorism in Africa: defining, addressing and understanding its impact on human security, Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2009, p.60

[vi] Da’wah Coordination Council of Nigeria, (DCCN) “Boko Haram” Tragedy: Frequently Asked Questions (Minna: DCCN, 2009), p.14

[vii] Y. Alli, “Boko Haram Kingpin, five others arrested, The Nation, 29 September 2011,

[viii] F. C Onuoha (2012), p.3

[ix] C.N Okereke, and V. E Omughelli, V.E “Financing the Boko Haram: Some Informed Projections”, African Journal for the Preventing and Combating of Terrorism, Vol. 2, No.1, (2012) esp. pp. 169-179.

[x] J Boone, “Taliban target mobile phone masts to prevent tipoffs from Afghan civilians”, 11 November 2011, The Guardian, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/nov/11/taliban-targets-mobile-phone-masts?newsfeed=true

[xi] N. Shachtman, “Taliban Threatens Cell Towers”, 25 February 2008, http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2008/02/in-iraq-when-th/

[xii] A. J. Rubin. “Taliban Using Modern Means to Add to Sway”, New York Times, 4 October 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/05/world/asia/taliban-using-modern-means-to-add-to-sway.html?_r=2&ref=technology&

[xiii] A. Ojedobe, “Mobile Phone Deception in Nigeria: Deceivers’’ Skills, Truth Bias or Respondents’ Greed?, American Journal of Human Ecology Vol. 1, No. 1, 2012, 1– 9

[xiv] D. Oketola, “Telecoms industry remains attractive after $254bn Investment – Report”, Punch, 16 Februar 2013.

[xv] E. Okonji, “Replacement of Damaged Base Stations to Cost Telcos N16bn”, Thisday, 7 January 2013, p. 1.

[xvi] S. Iroegbu, “FG to Provide Toll-free Lines to Tackle Boko Haram”, Thisday, 27 July 2011, http://www.thisdaylive.com/articles/fg-to-provide-toll-free-lines-to-tackle-boko-haram/95784/

[xvii] F.S. Iqtidaruddin, “Nigeria’s Boko Haram threatens to attack telecom firms”, Business Recorder, 14 February 2012, http://www.brecorder.com/world/africa/45736-nigerias-boko-haram-threatens-to-attack-telecom-firms-.html

[xviii] E. Okonji, (2013), p.1

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Why Time Matters When Proscribing Terrorist Groups

- Nigeria’s Soft Power in the Face of COVID-19

- Opinion – Nigeria’s Readiness to Fight Corruption and End Poverty

- Opinion – Nigeria’s Stagnation on Anti-Corruption Links with Growing Insecurity

- Opinion — Nigeria-China Relations: Sovereignty and Debt-Trap Diplomacy

- Iterability and Newsweek’s Paradigm of Nigeria as ‘Black China’