“[O]ur war on terror is only beginning…. Iran aggressively pursues these weapons [of mass destruction] and exports terror…. States like these, and their terrorist allies, constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world.”

Remarks in the State of Union Address by Bush, George W., January 2002.

“[T]he entire world has an interest in preventing Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon… an Iranian nuclear weapon could fall into the hands of a terrorist organisation… when it comes to preventing Iran from obtaining and nuclear weapon, I will take no options off the table…. That includes all elements of military power.”

Remarks to the AIPAC Conference by Obama, Barack H. 4 March 2012.

Introduction

The phrases ‘war on terror’ and ‘axis of evil’ are met with disdain in many circles of social and political life in 2013 – over a decade after George W. Bush said them in January 2002. However, much of the same language can be seen in President Obama’s words very recently. Eight months after his January 2002 State of the Union Address, George W. Bush made a speech to the UN General Assembly in order to call for Iraq’s disarmament or military force. Five days after Obama’s speech to the pro-Israeli American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) in 2012, President Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel warned he would not delay in attacking Iran’s nuclear sites if he felt it necessary (BBC News 2012a).

The research that follows is not a comparison between the events leading to the Iraq War in 2003 and recent events towards Iran. However, the invasion of Iraq has led many to question why 78% of the American population supported the removal of Saddam Hussein in November 2001 (Huddy, Khatib et al. 2002). And why is Obama’s language, which so closely reflects the Bush Administration’s, not met with greater enquiry both domestically and internationally? In light of these questions, this research will analyse how politicians frame adversaries in such a way as to manufacture public consent for action against other states through discoursal practice.

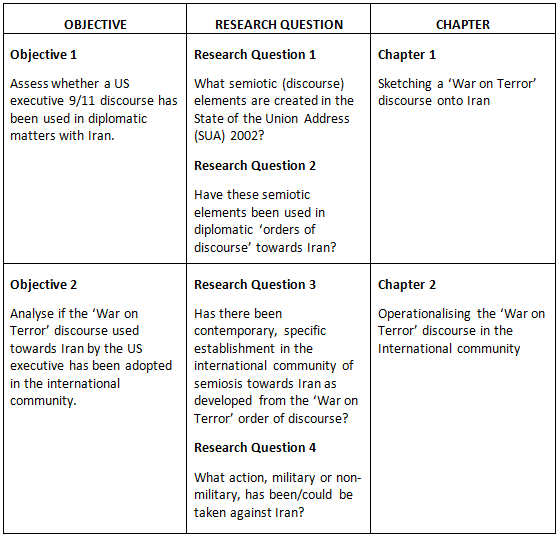

In an attempt to address this issue, I will be employing Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as described by Norman Fairclough (2010), Teun A. Van Dijk (2001), and Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer (2009), in combination with frameworks for analysing legitimating devices in discourse as developed by Theo van Leeuwen (1999, 2007) and Antonio Reyes (2008, 2011). Thereafter, the objectives of this research are to employ these tools to analyse a ‘9/11’ discourse that was created in 2002 and has been used in political discourse towards Iran, and how discourse can be extended into the international political arena to legitimise military action.

In his inaugural speech in 2010, Obama said, ‘[t]o the Muslim world, we seek a new way forward, based on mutual interest and mutual respect…we will extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist’. Is it not reasonable to argue that this demonstrates that the ideology of the Bush doctrine died along with his incumbency? Am I, as the author of this research ‘framing’ the issue through carefully selected sound bites based on a personal bias against the US? I do not believe in complete objectivity of research, however, the analysis throughout this dissertation will demonstrate a clear line of inquiry into how Obama’s words above have transformed into language almost synonymous with Bush’s in 2002. This evidence suggests that global institutions provide frames for action that constrain wider choices available to social actors because the dominance of particular discourses linked to social practices are maintained and reproduced across societies.

If this is found to be the case, CDA can provide frameworks to uncover how a 9/11 discourse can be normalised to such an unconscious extent that even an agent such as the US President becomes victim to them. Thereafter, recontextualisation of these semiotic elements could be sketched onto the Iranian issue to allow any degree of action internationally because the pre-existing ideological context greatly facilitates agents’ utilisation of legitimating strategies across global institutions.

Literature Review

September 11, 2001 was an unprecedented international event. As described by Patricia L. Dunmire (2009), this has been seen as a ‘disjuncture’ in history, demarcating the 21st century from the rest of history. However, Dunmire wishes to show in her article ‘”9/11 changed everything” an intertextual analysis of the Bush Doctrine’ that the US government used the event of 9/11 to construct this disjuncture, and, furthermore, to legitimise international action against potential adversaries thereafter. Dunmire sees that the 2001 attacks were used to legitimise a post-9/11 national policy which can be intertextually linked to an American foreign policy position stretching back to 1989 at the end of the Cold-War (2009: 196-197). ‘Intertextuality’, as defined by Martin Reisigi and Ruth Wodak (2009: 90), ‘means texts are linked to other texts, both in the past and in the present.’ Discourses are made up of these texts (oral, written and visual) which are related to ‘genres’. Van Leeuwen (2009: 144) defines ‘genres’ as formations of language in connection with actual social action.

The US post-Cold-War discourse has been described in a genre of ‘New World Order’ discourse (Lazar and Lazar 2004). Dunmire says that after 1989, in light of a threat blank, the US took the opportunity to re-orientate their security policy from a threat-based to a capability-based policy, in an attempt to maintain US global hegemony over friend or foe (Dunmire 2009: 209). Conservative voices, foremost amongst them Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, attempted to blur the distinction between pre-emptive and internationally illegal, preventive action against potential enemies (Dunmire 2009: 205). Hostility to such policies in Congress, and the Clinton administration coming to office in 1993, left Cheney’s ideas largely unfulfilled. However, Dunmire’s argument is that 9/11 provided the platform on which to bring policies based on neo-conservative ideology to fruition, with many of the original architects already holding positions in the Bush administration after the 2000 Presidential election (Dunmire 2009).

This ideological positioning is important. Firstly, as described by Trita Parsi (2012), it may go some way to explaining why the Bush administration refused to enter negotiations with Iran in 2003 and, secondly, because such beliefs can permeate into society to legitimate political action. The aim of Norman Fairclough’s tenet of CDA (2010: 30-45) is to ‘demystify’ these ideas, beliefs, and norms which exist within ‘unconscious’ ideology that maintain unequal power relations in social and political life. Fairclough describes how legitimating strategies employed by social actors constitute wider macro-strategies whereby social agents, such as government officials, and politicians (including the President) utilise semiotic elements of discourse in particular articulations to achieve their individual goals (Fairclough 2010: 166). If the goal of neo-conservative foreign policy goals has been to maintain US global supremacy in the world since the early 1990s this has been aided by an unabashed use of language loaded with words like pride, anger, fear, hope, terror, hero, and freedom since 9/11, as proved by Frederica Ferrari (2007: 16).

Dunmire (2009) and John Oddo (2011) go on to demonstrate how vague US governmental documents are when defining ‘threat’, especially in the National Security Strategy document released in 2002. The purpose of this loosely defined language is to legitimise action against any perceived or later identified enemies, allowing the US to act preventively against a great range of threat where they deem fit (Dunmire 2009, Oddo 2011). John Oddo (2011) provides a working analysis for Fairclough’s tenant of CDA by demonstrating how political leaders can create an Us/Them binary through a semantic macro-strategy of positive self-image and negative image of the other to legitimise action for war. Oddo (2011: 289) writes that by ‘representing an enemy that is completely evil and ready to strike, the discourse practically necessitates only one course of action: wipe them off the face of the planet’. Thus, to quote the former Secretary of State Hilary Clinton in 2008, ‘at whatever stage they [Iran] might be at their nuclear weapons programme…we would be able to totally obliterate them’ (Veracifier 2008). Therefore, Fairclough (2010) would argue that once ideologically loaded language such as above is reified into a ‘war on terror’ discourse, the language used can be ‘recontextualised’ into a discourse towards Iran due to the effects of ideology unconsciously occupying areas of national foreign and security policy. One need only refer back to the similarities in Bush and Obama’s language to see how it is possible that such discourses have indeed permeated American society and governmental ideology. Subsequently, according to Fairclough (2010: 163), this gives CDA a dual focus; firstly, on the structure of social practices, and secondly, on the strategies that social agents employ when attempting to achieve certain outcomes.

Van Leeuwen (2009) explores the strategies that agents employ in ‘Discourse as the recontextualization of social practice: a guide’. He discusses how social actions can be broken down into constitutive elements that actors are able to recontextualise into specific discourses. One of these elements is described as ‘addition’, formed of two parts, ‘reactions’ and ‘motives’. Reactions are the mental processes that accompany actions such as interpretation, and motives detail purposes or legitimations (Van Leeuwen 2009: 150-151). It is these legitimations that ‘provide reasons for why practices (or parts of practices) are performed’ (Van Leeuwen 2009: 151). Furthermore, according to Van Leeuwen, reasons for social action need not be explicitly brought out in discourse but can be communicated through a ‘moral evaluation’ (2009: 151).

Van Leeuwen (2007) has developed a framework to use as a tool in identifying these legitimising strategies. It is made up of four categories of legitimisation: ‘authorisation’ through reference to tradition, law or an individual holding institutional authority; ‘moral evaluation’ by using discourses linked to values; ‘rationalisation’ which points to the capability of institutional action based on social knowledge as a form of validity and; ‘mythopoesis’ to create narratives of legitimation that benefit ‘legitimate’ agents and conversely punishing ‘non-legitimate’ agents. Antonio Reyes (2011) has largely adapted this model to analyse speeches from George W. Bush and Barack Obama on conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan positioned within the wider ‘war on terror’. He conducts his analysis based on five strategies of legitimisation: 1) emotions (particularly fear); 2) a hypothetical future; 3) rationality; 4) voices of expertise, and; 5) altruism. His work highlights how agents can more easily legitimise seemingly separate, individual events because the discursive tools needed in any given area can be called upon because they are already pervasive in society (Reyes 2011: 781).

Therefore, in the historical context set by Dunmire (2009) and Oddo (2011) amongst others, I will take Fairclough’s (2010) model as my starting point for the use of CDA in this dissertation. Thereafter, frameworks for the analysis of speeches from Van Leeuwen and Reyes will greatly inform my own examination, in order to discover how a ‘war on terror’ discourse can be operationalised into international social action against Iran.

Methodology

I will employ Norman Fairclough’s (2010) Dialectical-Relational approach of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as my methodology for this research. In this model, Fairclough’s endeavour is to identify a semiotic ‘point of entry’ to overcome the obstacles that are preventing change to ‘social wrongs’ (2010: 239). Namely, these obstacles are the hegemonic struggle by ‘orders of discourse’ that dominate and integrate (dialectically) competing discoursal ideologies to maintain prominence in social and political life. Within this framework a point of entry into the hegemonic cycle can be created by a new discoursal practice, which will be discussed below.

In his approach, Fairclough (2010) uses ‘semiosis’ as a more accurate term for ‘discourse’. He emphasises that semiosis is one part of any particular social process in society as they also constitute non-discursive elements such as visual imagery and body language. So, it follows that a specific catalogue of these aspects is required to develop or cause action in society in the form of social practices. An example of a social practice is the US government’s response through sanctions to Iranian nuclear proliferation; therefore, practices are bound to social institutions and social events. Social structures are broadly defined as institutions, such as the executive office of the United States, the White House, British Government etc. and serve to mediate between social practices and ‘particular and concrete social events’ (Fairclough 2010: 164). For example, the White House acted as an intermediary in the abstract concept of American liberal democracy and the interpretation of 9/11 as an international social event. The use of ‘semiosis’ also serves a practical purpose as Fairclough distinguishes certain elements of semiosis, one of which being ‘discourse’, the others ‘genres’ and ‘styles’. These elements then correlate to three areas of semiosis:

- Discourse → construal of aspects of the world

- Genre → facets of action

- Style → constitution of identities

How these elements interact and contest one another forms the particular discoursal nature of the social practice. The social practice can be changed by ideological shifts in any one of the elements because this will affect its relation to the other elements and areas of the practice. Where the social practice changes, this has a wider effect on social structures and, so, the interpretation of social events also.

Subsequently, the semiosis of the social practice can be ‘operationalised’, or ideologically accepted, in and across societal institutions because an ‘order of discourse’ is created as ‘networks of social practices’ are established. This is because the interaction of the semiotic elements in the social relations between institutions across time and space allows ideology to be accepted and remain in action (Fairclough 2010: 163). Correspondingly, networks of social events produce particular discoursal ‘texts’. Where texts develop intertextuality can be found, which is an aspect of ‘interdiscursivity’ that shows how texts are made up ‘of diverse genres and discourses’, and it ‘highlights a historical view of the past… in the present’ (2010: 232, 95). Texts refer to the, ‘written or spoken language produced in a discursive event’, with a ‘discursive event’ being an, ‘instance of language use’ (Fairclough 2010: 95).

In other words, it was possible to create a specific social practice (invasion of Iraq, Afghanistan, special rendition) after 9/11 by using a neo-conservative ideology to shift the relations of the semiotic elements that produce certain texts in relation to America’s ‘enemies’ based on particular combinations of texts from the past into the present. Thereafter, the attempt to transfer this discourse onto the Iranian issue is defined as ‘recontextualisation’ (Fairclough 2010: 163-164, 232-234).

Recontextualisation takes on an ambivalent nature because social agents attempt to colonise certain fields and institutions with discourse from other areas in line with a particular strategy. The place at which recontextualisation occurs creates legitimation for action and forms the crux of this research as we attempt to uncover if a post-9/11 discourse is being employed by politicians internationally to legitimate action against Iran.

Once the original ‘war on terror’ discourse is created in 2002, Fairclough warns that it can become unconsciously accepted and employed throughout the US executive into policy options through obtaining dominance over other discourses. The order of discourse competes for hegemony because social agents attempt to advance its particular ideological position, which is defined as a ‘discoursal practice’ (Fairclough 2010: 62). Subsequently, an order of discourse becomes dominant as it is taken on unconsciously and is difficult to change because the discourse maintains itself by reproduction into other areas of society (Fairclough 2010: 41-43). Therefore, it could be argued that demonstrating the recontextualisation of a ‘war on terror’ discourse towards Iran will give us a point of entry into breaking the hegemonic cycle that reproduces and creates a preponderance for military policy options in Washington and the rest of the world. This will create a new discoursal practice that presents a more complete picture of the Iranian issue, allowing us to overcome the obstacle of an incomplete truth.

CHAPTER PLAN

Chapter One: Sketching the ‘War on Terror’ Discourse onto Iran

This chapter analyses the State of the Union Address 2002 through a discursive analytic framework to identify what semiotic elements were created. This is then directly compared against Obama’s State of the Union Address 2012, and his American Israeli Public Affairs Committee speech in March 2012, to establish how the ‘war on terror’ discourse has been recontextualised towards the semiotic construction of Iran.

Chapter two: Operationalising the ‘War on Terror’ Discourse in the International Community

The conceptual linkage of interdiscursivity and hegemony of discourse is discussed, with evidence presented to suggest the ‘war on terror’ discourse has been operationalised in the international community through this process. It is then shown how the order of discourse has developed to convey main concerns about nuclear proliferation combined with an increasingly ambivalent tone towards Iran. Analysis then briefly introduces other international discourses that are contrary to the presented norms of the ‘war on terror’ discourse in an attempt to demystify shared beliefs and offer a new discoursal practice in the debate over Iran.

CHAPTER ONE: Sketching the ‘War on Terror’ Discourse onto Iran

The process of ‘recontextualisation’ as described by Fairclough and Van Leeuwen is the procedure by which semiosis in a ‘war on terror’ discourse can be operationalised into political discourse specific to Iran. It is in this light that we approach the objectives of this chapter. Firstly, through the application of a discursive analytical framework onto G.W. Bush’s State of the Union Address 2002 (SUA02) the semiotic elements that are used to develop a ‘war on terror’ discourse were identified. Secondly, the results from this process were compared with President Barack Obama’s SUA in January 2012 (SUA12) and his speech to the American Israeli Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) in March 2012. Obama’s SUA12 was chosen as a key Presidential speech to the American public where he addresses foreign policy issues, and the AIPAC speech as a key Middle East foreign policy speech.

The framework applied to Bush’s SUA02 is largely an adaptation of the strategies identified by Antonio Reyes, introduced in the literature review above. My framework demonstrates three key strategies that actors employ to legitimise action: 1) an appeal to emotions that evoke a sense of fear; 2) speech proposals of a hypothetical future, and; 3) rationality of the decision process. This was also informed by Van Leeuwen’s (2007) four categories of legitimisation – ‘authorisation’, ‘moral evaluation’, ‘rationalisation’ and ‘mythopoesis’.

By identifying direct utterances from the SUA02 to Obama’s language from a strict list of findings this could lead me to overlook occurrences of recontextualisation that may inform my wider evaluation. However, I have chosen this process because it denies any extra interpretation on my part as the researcher that may lead me to more subjective conclusions. In any case, as is shown in the analysis that follows, there is substantial evidence to suggest recontextualisation has occurred.

Strategy 1: An Appeal to Emotions That Evoke a Sense of Fear

In the first strategy, speakers evoke certain feelings by making reference to emotions through their speech. By appealing to emotions that give the audience a sense of fear, action is legitimised as a necessary precaution to avert the consequence the speaker is proposing (Reyes 2011) – live or die may present equally strong feelings but they are at quite different ends of a broad spectrum. A key feature to achieving this strategy is the construction of the adversary, ‘them’, in relation to the familiar group, ‘us’ (Wodak and Meyer 2001). Wodak (2001, 2002) describes how this distinction is created through three speech strategies – referential, nomination, and predicative – to construct the other.

Firstly, ‘referential’ strategies develop systems for referring to the enemy, i.e. terrorists, extremists, regimes etc as can be seen in Bush’s language in (1):

(1) [T]he terrorists and regimes who seek chemical, biological or nuclear weapons (Bush 2002).

In (1), the referential strategy used to identify ‘terrorists and regimes’ is bound to the pursuit of weapons that evokes a sense of fear. Therefore, they become intertextually linked to the language in (2) and (3) from Obama:

(2) The regime [Iran] is more isolated than ever before (Obama 2012a).

(3) No Israeli government can tolerate a nuclear weapon in the hands of a regime [Iran]that denies the holocaust, threatens to wipe Israel off the map, and sponsors terrorists groups committed to Israel’s destruction (Obama 2012b).

Furthermore, a dramatisation of the enemy’s actions appeals to fear responses through a tactic, introduced by Reyes (2008: 34), called ‘Explicit Emotional Enumeration’ (EEE). ‘Politicians state the threat enumerating the negative actions of the enemy (EEE) and they provide the solution (war) to eliminate that threat’ (Reyes 2008: 35). This strategy is realised by breaking the object under discussion into a descriptive list, whilst presenting no new information to the listener. It is purely used as an appeal to emotions (Reyes 2008). Excerpt (1) above demonstrates the breakdown of weapon types, where (4) shows EEE in reference to terrorist groups:

(4) A terrorist underworld – including groups like Hamas, Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad, Jaish-i-Mohammed (Bush 2002).

The EEE in this case, then, allows simplified reference through intertextuality to these groups as they have been explicitly named beforehand. This is seen in (5) by using the referential phrase ‘Iran’s proxies’:

(5) [I]t would embolden Iran’s proxies, that have carried out terrorists attacks from the Levant to Southeast Asia (Obama 2012b).

This strategy can also be used to define the victims of terrorism, demonstrating that the ‘other’ does not discriminate in their attacks. In (6), Bush describes events in Iraq to demonstrate his point. In (7), Obama recontextualises this to Iran:

(6) This is a regime that has already used poison gas to murder thousands of its own citizens – leaving the bodies of mothers huddled over their dead children (Bush 2002).

(7) We will stand for the rights and dignity of all human beings – men and women; Christians, Muslims and Jews (Obama 2012b).

The joint effort of referential strategies in describing what the ‘other’ is, and the appeal to emotion that the speaker can achieve through EEE, provides the initial building block towards constructing the adversary. This image can then be brought to life by the second strategy of ‘nomination’.

Nomination strategies refer to ‘[w]hat traits, characteristics, qualities, and features are attributed to them?’ (Wodak, Meyer 2001: 73), i.e. killers or murderers. Essentially, this constructs what threat the ‘other’ presents to the listener:

(8) We have seen the depth of our enemies’ hatred in videos, where they laugh about the loss of innocent life (Bush 2002).

(9) Thousands of dangerous killers, schooled in the methods of murder (Bush 2002).

As part of my discursive framework, I applied a Transitive Model from Systemic Functional Grammar (SFG) as developed by Michael Halliday (Halliday, Matthiessen 2004), to outline verbal, mental and material verb-types. Specifically chosen verbs are linguistically linked to the nouns that ‘nomination’ strategies wish to highlight. In (10), the noun ‘regime’ becomes linked to material verb-type ‘brutalised’ and in (11) ‘Iran’ is linked to mental verb-type ‘threaten’. Both examples below are from Obama:

(10) … a regime that has brutalised its own people (Obama 2012b).

(11) And we will safeguard America’s own security against those who threaten our citizens, our friends, and our interests. Look at Iran (Obama 2012a).

This is not dissimilar to Bush in 2002, where in (12) ‘Iran’ is linked to both ‘pursues these weapons’, ‘exports terror’ and ‘repress’, which are certainly material but also mental verb-types, and (13) links ‘regimes’ with ‘sponsor’, ‘threatening’ also as material and mental:

(12) Iran aggressively pursues these weapons and exports terror, while an unelectedfew repress the Iranian people’s hope for freedom (Bush 2002).

(13) Our goal is to prevent regimes that sponsor terror from threatening America or our friends and allies with weapons of mass destruction (Bush 2002).

Halliday’s (2004) work demonstrates how particular nouns that have pre-existing ideological meanings are distinguished for recurring use in certain discourses. This means speakers can use these words efficiently when constructing discourse as they do not need to explain their disagreement towards them at each use. Furthermore, Bush’s use of ‘aggressively’ in excerpt (12) demonstrates the third ‘predicative’ strategy.

In order to cement an appeal to the listener’s emotions, ‘predicative’ strategies attach particular attributes to the ‘other’ in order to emphasise the extent of the threat. This is achieved by using a clause or adjective to state something about the subject beyond the initial understanding of a verb or noun (Halliday, Matthiessen 2004). Key to our study is the recontextualisation from the predicates Bush attaches to the general nouns ‘regimes’ and ‘weapons’ in (14), to the specific case of Iran in Obama’s speech in (15):

(14) The United States of America will not permit the world’s most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world’s most destructive weapons (Bush 2002).

(15) Iran’s nuclear program – a threat that has the potential to bring together the worst rhetoric about Israel’s destruction with the world’s most dangerous weapons (Obama 2012a).

Furthermore, once the predicative strategy has been employed, and the predicate accepted by the listener, an argumentation tactic is used to build a scenario where this may become reality for the listener.

Argumentative strategies allow ‘specific persons or social groups [that] try to justify and legitimise the exclusion, discrimination, suppression and exploitation of others’ (Wodak and Meyer 2001: 73; Wodak and Pelinka 2002). This can allow the speaker to achieve highly persuasive utterances to legitimise actions that become naturalised into social practices of exclusion and discrimination through a description of what the ‘other’ has done (Reyes 2011). In (16), Bush is describing Iraq’s actions towards weapons inspectors that ultimately constituted the main argument for the US invasion in 2003:

(16) This is a regime that agreed to international inspectors – then kicked out the inspectors (Bush 2002).

Essentially, where the ‘argument’ of the speaker succeeds, some form of social action will transpire because this is a microcosm of the struggle for predominance between orders of discourse as described by Fairclough. The predominance of the ‘war on terror’ order of discourse in American political and military institutions gives Obama’s recontextualisation of nuclear proliferation issues with Iran in (17) added significance:

(17) But a peaceful resolution of this issue is still possible, and far better, and if Iran changes course and meets its obligations, it can rejoin the community of nations (Obama 2012a).

This is of great pertinence here because it would seem that the revelations of not finding WMDs in Iraq should create a reluctance of the public to accept any actions towards Iran on the same basis. However, this feeling is anesthetised because of the perennial emotional appeal of what Iran represents that is constructed in the ‘war on terror’ discourse, which has been recontextualised to the Iranian issue.

Therefore, an appeal to emotions in the Iranian case is cemented by the employment of referential, nomination and predicative strategies, supported by an argumentative strategy to show what they have actually done. This evokes a sense of fear in the audience as ‘they’ are distinguished from ‘us’, and so the next stage to gaining acceptance for action is the hypothetical circumstances this situation may lead us to.

Strategy 2: Speech Proposals of a Hypothetical Future

The second strategy proposes circumstances that may transpire if the speaker’s warnings or suggestions are not heeded. This is most effectively achieved through a linkage of problems in the past with the future to develop intertextuality, allowing the speaker to suggest immediate action in the present (Reyes 2011).

Key to accomplishing legitimisation here are conditional structures that employ ‘markers of modalisation’ such as would and could, to allow speculation on future events (Reyes 2011: 794). Bednarek (2006: 21-23) describes this as ‘epistemic modality’ that ‘conveys the speaker’s degree of confidence in the truth of the proposition’. Excerpts (18) and (19) demonstrate how general hypothetical future structures constructed by Bush have been recontextualized specifically to Iran by Obama. Interestingly here, Obama gives a detailed scenario of what could happen, which further appeals to the listeners’ emotions:

(18) By seeking weapons of mass destruction, these regimes pose a grave and growing danger. They could provide these to terrorists, giving them the means to match their hatred. They could attack our allies or attempt to blackmail the United States. In any of these cases, the price of indifference would be catastrophic (Bush 2002).

(19) There are risks that an Iranian nuclear weapon could fall into the hands of a terrorist organisation. It is almost certain that others in the region could feel compelled to get their own nuclear weapon, triggering an arms race in one of the world’s most volatile regions (Obama 2012b).

Furthermore, actors can propose a hypothetical future without epistemic modality, which suggests complete confidence in the proposition to give the statement added significance. Again, Bush’s general words about terrorism are recontextualized by Obama to Iran:

(20) So long as training camps operate, so long as nations harbour terrorists, freedom is at risk (Bush 2002).

(21) A nuclear armed Iran is completely counter to Israel’s security interests. But it is also counter to the security interests of the United States (Obama 2012b).

Over the course of my analysis it became clear that Obama presents statements without epistemic modality much more frequently than Bush. This suggests something about his personal oratory style and shows that when this is constructed as part of a fearful scenario, the future becomes a place where political actors can situate ideological utterances in order to exert power and control (Dunmire 2009).

Another element of the hypothetical future strategy is reference to altruistic motivations. A hypothetical future that benefits others through proposed action allows the speaker to avoid suggestions that their wider motives are self-interested (Reyes 2011). Bush refers to the invasion of Afghanistan that happened shortly before his SUA02 in (22):

(22) The last time we met in this chamber, the mothers and daughters of Afghanistan were captives in their own homes, forbidden from working or going to school. Today women are free, and part of Afghanistan’s new government (Bush 2002).

Many of the same themes can be seen in (23) from Obama, relating to rocket fire from Palestinian militants in Gaza:

(23) [A]s President, I have provided critical funding to deploy the Iron Dome system that has intercepted rockets that might have hit homes and hospitals and schools in that town and in others. Now our assistance is expanding Israel’s defensive capabilities, so that more Israelis can live free from the fear of rockets and ballistic missiles (Obama 2012b).

In both (22) and (23) EEE can be identified – Bush refers to the victims whilst Obama makes reference to civilian buildings. What is interesting in Obama’s speech is the connection to ballistic missiles that relates to wider discourses linked to Saddam Hussein’s scud missile attacks on Israel in the 1991 Gulf War. This technology is outside the capability of Gaza militants such as Hamas but is still referred to here as it becomes intertextually linked to Obama’s words as he identifies ‘Iran’s proxies’ shown in excerpt (5), above.

Further to altruistic references, the protection of values is presented as a legitimising tactic, which is described by Van Leeuwen (2009) as ‘moral evaluation’. The speaker uses a threat to value systems as a reason for social action (Reyes 2011). Excerpts (24) and (25) show how many of the themes in Bush’s language are picked up by Obama as he makes reference to Iran, showing recontextualisation:

(24) America will stand firm for the non-negotiable rights of human dignity: the rule of law; limits on the power of the state; respect for women; private property; free speech; equal justice; and religious tolerance (Bush 2002).

(25) The United States and Israel share interests, but we also share those human values Shimon spoke about: a commitment to human dignity, a belief that freedom is a right that is given to all of God’s children (Obama 2012b).

The semiosis here demonstrates the pervasiveness of the hypothetical future strategy because, as Reyes (2011: 795) states, ‘[t]hese legitimisations do not respond to an ideological position, nor are they idiosyncratic characteristics of a particular political actor’ (democrat, republican, liberal, or realist), they are simply presented as American. This greatly facilitates the process of recontextualisation as it allows the actor to extend the demonization of the abstract ‘other’ to real perceived threats, such as Iran (Reyes 2011).

Therefore, it can be seen how recontextualisation from a ‘war on terror’ discourse can aid the construction of Iran as the enemy in strategy 1, and the hypothetical threats they pose suggested in strategy 2 can make an audience accept the challenges Iran presents. However, the break between the threat and the proposed action against it still needs to be traversed in order to legitimise action. This is done by demonstrating the rationality of the actions taken against those threats.

Strategy 3: Rationality of the Decision Process

The third strategy presents the decision to conduct social practices as rationally considered, in order to present them as the right thing to do (Reyes 2011). This process can only occur within a shared belief system of society that defines what is ‘right’. Therefore, actors can identify what is culturally considered as an acceptable approach to decision making and situate their actions within this operating system to legitimise action (Reyes 2011).

A key element to this strategy is the process of naturalisation that occurs, especially once a demonisation of the ‘other’ is complete via strategy 1. If a context is constructed where the threat of the ‘other’ is just ‘the way things are’, this belief system can be naturalised in society (Reyes 2011: 798). This allows the actor to provide a limited catalogue of the options for action whilst presenting it as complete. Furthermore, a greater effect is to demonstrate that these options have been produced through a diligent process of wider consultation. This allows the reinforcement of the Us/Them binary by reassuring listeners that there is support for proposed actions. The similarities between Bush’s words in (26) and Obama’s in (27), as he talks about economic sanctions against Iran, are stark:

(26) America is working with Russia and China and India, in ways we have never before, to achieve peace and prosperity…. Together with our friends and allies from Europe to Asia, and Africa to Latin America, we will demonstrate that the forces of terror cannot stop the momentum of freedom (Bush 2002).

(27) Some of you will recall, people predicted that Russia and China wouldn’t join us to move toward pressure. They did…. Many questioned whether we could hold our coalition together as we moved against Iran’s central bank and oil exports. But our friends in Europe and Asia and elsewhere are joining us (Obama 2012b).

Support can be stated but does not necessarily generate support in itself, so an important discursive device is to back up the legitimation of social action through stating the outcome to the listener. Obama follows his statements in (27) with:

(28) That is where we are today – because of our work. Iran is isolated, its leadership divided and under pressure (Obama 2012b).

Excerpt (28) demonstrates rationality based on the success of the action to show that the social practice produced an intended outcome. This is described as ‘instrumental rationality’ by Van Leeuwen (2007), and gives the purpose of the social practice to the listener. However, purposes are not synonymous with legitimations, so to achieve such acceptance a moralisation can be attached to the purpose to fully take advantage of the legitimation strategy. In both Bush’s and Obama’s language, this moralisation is stated as defence of the nation:

(29) We will work closely with our coalition partners to deny terrorists and their state sponsors the materials, technology and expertise to make and deliver weapons of mass destruction…. All nations should know: America will do whatever is necessary to ensure our nation’s security (Bush 2002).

(30) I have a policy to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon. And as I have made clear time and time again during the course of my presidency, I will not hesitate to use force when it is necessary to defend the United States and its interests (Obama 2012b).

This is clear recontextualisation from Bush’s words that vaguely identifies ‘state sponsors’ with the production of WMDs, with Obama’s words that simply sketch this scenario directly onto Iran. The turn towards military action is representative of an ideological position that, it can be argued, has infiltrated the US executive. Excerpts (29) and (30) show how morally acceptable rationalisations can legitimate action because the possession of, or the progress towards, a nuclear weapon is now linguistically linked to the US ‘use of force’. What ‘necessary’ action entails is withheld from the listener, but the practice is legitimised because society accepts it on the basis of its morality, i.e. to defend the United States, which naturalises it as just the way things must be.

Summary

The analysis above demonstrates the recontextualisation of Bush’s wider ‘war on terror’ discourse towards Iran by Obama in 2012. Furthermore, the linkage of the three strategies is clearly evident. The construction of the enemy in strategy 1 appeals to the listener’s emotions, allowing the development of hypothetical futures in strategy 2 based on the enemies identified characteristics. This picture of the ‘other’ is bridged into the reality of social practices by strategy 3, which demonstrates rationality of the decision making process. The analysis in this chapter shows that where particular reference to emotions exists, as we would expect to see in discourse relating to the September 11 attacks, highly persuasive textual structures have the potential to legitimise many forms of social action. This is made possible by changes in the semiosis that corresponds to social practices by altering one, two, or all three of its elements.

9/11 is a clear example of how a social event caused the elements of the existing order of discourse to shift by altering society’s perception of the world. This facilitates new forms of social action so that, where recontextualisation occurs onto the Iranian issue, the practices legitimised by reconfiguration of the order of discourse in 2002 would be expected to reoccur where the same discourse informs the social events of 2012 and beyond. Where changes were indeed achieved in 2002, a ‘war on terror’ discourse would be naturalised as part of specific social practices into a linkage of ‘the world’s most dangerous regimes…pursue…weapons of mass destruction…’ (Bush 2002), and ‘I will take no options off the table…aimed at isolating Iran…and, yes, a military effort to be prepared for any contingency’ (Obama 2012b). However, in the case of a move towards military action against Iran, if the ‘war on terror’ discourse can be ‘operationalised’ in the international community such action could achieve greater support and legitimation.

CHAPTER TWO: Operationalising the ‘War on Terror’ Discourse in the International Community

In order to gain international support for any proposed action towards Iran, the ideology has to be accepted and reproduced in the international community through the process of ‘operationalisation’. Firstly, international support against Iran will further solidify the Us/Them polarisation. Secondly, it will allow the demonstration of wider support and diligent process that satisfies legitimation strategy 3. And thirdly, it could generate authorisation for action through such institutions as the United Nations (UN).

In order to explore this process, this chapter will discuss the concepts of interdiscursivity and hegemony, and their linkage as the two key facets in the process of operationalisation. The analysis will then turn to direct examples of the ‘war on terror’ discourse through speeches to the UN General Assembly in 2012 from President Obama and Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, with further examples from press conferences with the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, David Cameron, and other foreign ministers from Europe. Speeches from the UN General Assembly were specifically chosen, as the UN is an international body that all parties in this discussion recognise through the UN Charter and actively use as a mediator for debate (United Nations). Furthermore, the UK, France and the US are all permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), and so have the opportunity to significantly affect the topics for discussion and decisions within this body (United Nations Security Council 2012). Following the analysis proposed above, I will present other contemporary professional voices that oppose the ‘war on terror’ discourse such as the Political and Academic Delegation to the European Union (EU), leading US policy experts Colin Khal, Gary Sick, and Mark Fitzpatrick, along with former UN Chief Weapons Inspector, Hans Blix. However, these discourses seem to have been left out of popular discussion on the Iranian issue, and so I present them below as an attempt to ‘demystify’ common belief by presenting a broader picture of the issues at hand.

Operationalising Discourse: Interdiscursivity and Hegemony

Norman Fairclough’s work makes it clear that interdiscursivity and hegemony form the two key concepts in the operationalisation process (2010: 95). Interdiscursivity demonstrates the limitless configurations of genres and discourses that are possible based on a myriad of interpretations of the world – but these alternate understandings of the world are limited in practice by the hegemonic struggle of dominant orders of discourse for prominence in societal institutions. The concept of hegemony is defined by Fairclough as ‘a contradictory and unstable equilibrium’ and is taken from the Gramscian concept of ideology as a composite of past struggles between competing interpretations of the world (Fairclough 2010: 62). For our purposes, it is these shifts in hegemonic forces that are of interest. If we can determine where we can change our interpretation of the Iranian issue, we can invite a marginalised discoursal practice to revaluate our opinion on policy options by our governments. This can engage in the struggle with the dominant discourse to hopefully tip the unstable equilibrium to reveal a clearer representation of the world.

It is the possible effects of a discoursal practice and interpretation on the dominant discourses that are of importance in this endeavour. A discoursal practice can reproduce the existing order of discourse, but it can also transform it by presenting new texts produced from social events. This is made possible by shifting semiotic elements (discourse, genres, and styles) through a re-interpretation of social events. However, the extent to which these texts’ meanings can fluctuate is greatly controlled by ‘particular configurations’ of the semiotic elements that social agents and institutions call upon to interpret events (Fairclough 2010: 63). However, an agent’s particular use of discoursal elements in interpretation does not counter all the possible configurations of discourse that interdiscursivity allows from a new discoursal practice. Therefore, hegemonic struggle in the Gramscian sense follows, as dominant groups continuously compete against such changes by forming alliances with rival discourses through small concessions and integration rather than merely domination (Fairclough 2010: 63). Subsequently, it can be seen that a reticulated ideological milieu is formed to maintain and reproduce the dominant order of discourse across institutions, which is contradictorily weakened over time through the same process.

It is in this light that we should undoubtedly turn our attention to the links between international institutions to reveal the hegemonic and interpretative processes, and attempt to create room for challenge from a new discoursal practice.

The International Community

The ‘war on terror’ discourse has developed through hegemonic struggle against discourse in the international arena. However, it originated locally in the United States after the 9/11 attacks, as demonstrated in the SUA02. The discourse achieved dominance across the US through the formation of an ideological matrix of institutions as they began to share and reproduce the ‘war on terror’ discourse by way of the hegemonic struggle described above. Thereafter, the US, as a state, began to integrate and disintegrate international institutions in the same way, facilitated by a world of increased interconnectedness and interdependence between governments. To show this, I would like to demonstrate the recontextualisation of the ‘war on terror’ discourse in the UN General Assembly speech by Benjamin Netanyahu on 27 September 2012.

This speech is overtly situated in the ideology of the ‘war on terror’ discourse and shows numerous features that can be determined in line with the application of my framework discussed in Chapter 1. Here, referential strategies can be seen in (31) that support emotional images of what the ‘other’ is and the threat that they present to ‘us’:

(31) Now, militant Islam has many branches, from the rulers of Iran… to al-Qaeda terrorists, to the radical cells lurking in every corner of the globe (Netanyahu 2012).

Excerpt (32) displays hypothetical future strategies and demonstrates the use of modality markers such as ‘could’ and ‘would’:

(32) [N]othing could imperil our common future more than the arming of Iran with nuclear weapons. To understand what the world would be like with a nuclear armed Iran, just imagine a world with a nuclear armed al-Qaeda (Netanyahu 2012).

Finally, rationality strategies are used by Netanyahu to demonstrate support for social action, and the instrumental rationality shown in their success:

(33) Under the leadership of President Obama, the international community has passed some of the strongest sanctions to date. I want to thank the representatives of governments that have joined in this effort, it has had an effect – oil exports have been curbed and the Iranian economy has been hit hard (Netanyahu 2012).

These aspects demonstrate that the same strategies as those in Chapter 1 are being employed by Netanyahu in international institutions and are linked intertextually to semiosis displayed through Obama’s speeches. In this instance, Netanyahu uses intertextuality to support his statements in this UN speech as he states, ‘[t]wo days ago from this podium, President Obama reiterated that the threat of a nuclear armed Iran cannot be contained’ (Netanyahu 2012). The Obama speech that Netanyahu refers to does indeed reiterate these opinions, and also demonstrates the operationalisation of the ‘war on terror’ discourse in the international institution of the UN General Assembly:

(34) In Iran… a violent and unaccountable ideology leads… continues to prop up a dictator in Damascus and supports terrorist groups abroad (Obama 2012c).

(35) [A] nuclear-armed Iran is not a challenge that can be contained. It would threaten the elimination of Israel…. It risks triggering a nuclear-arms race in the region (Obama 2012c).

(36) A coalition of countries is holding the Iranian government accountable (Obama 2012c).

Furthermore, the specific use of discoursal semiosis displayed by Netanyahu is evidence of the operationalisation into the Israeli government, which is thereafter representing these opinions in the UN to other governments. It could be argued that Israel is just one government and is not supported by others, therefore it is necessary to explore whether operationalisation through the processes of discoursal hegemonic struggle can be seen across other governments, to determine the limitation of interdiscursivity and the employment of intertextuality.

The discoursal examples from politicians of France, Germany, and Britain that I will demonstrate below represent the key negotiators in the Iranian nuclear talks since January 2011, led by the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Baroness Catherine Ashton (Reynolds 2011). The importance of the EU’s role is shown in David Cameron’s statement in a joint press conference on 14 March 2012:

(37) Britain has played a leading role in helping deliver an EU-wide oil embargo. Alongside the financial sanctions being led by America, this embargo is dramatically increasing the pressure on the regime (Obama, Cameron 2012).

Firstly, Cameron’s words suggest his support for the EU actions. Secondly, his use of the term ‘the regime’ demonstrates referential elements as this becomes intertextually linked with semiosis in past speeches from Bush and Obama. And finally, rationality can be seen by reference to the action being EU-wide to show support, and, more so, that it is instrumentally rational as they are ‘increasing the pressure’ on Iran. Obama, from his position of high international status, then goes on to directly support Cameron’s statements, raising Cameron’s profile in the eyes of the British public by the processes of ‘mythopoesis’ and ‘rationalisation’ presented by Van Leeuwen (2007). Joint press conference settings such as these demonstrate an interesting tactic which Fairclough names ‘synthetic personalisation’ (Fairclough 2010: 65). In this way, meetings between leading politicians are presented as personal affairs involving the audience, where access would otherwise be unavailable. This phenomenon demonstrates one of the other facets of the overarching definition of ‘discourse’ offered by Fairclough, which describes how semiosis and these other elements together form the ways individuals communicate with each other. So, synthetic personalisation can be seen as an attempt by social agents to overcome the distinction between public and private realms, and subsequently, between political and civil society to generate consent in private social circles and alleviate anxiety linked to conflict (Fairclough 2010).

The next example that I will present is a meeting between Netanyahu and the German Foreign Minister, Guido Westerwelle, on 9 September 2012. The ‘war on terror’ discourse is echoed in this meeting as we saw in the intertextuality of Netanyahu’s words above. The encounter between Westerwelle and Netanyahu also demonstrates the use of ‘synthetic personalisation’ as their meeting was staged in front of a large press audience (IsraeliPM 2012). At their meeting, Westerwelle said:

(38) [W]e condemn every kind of terrorist attack against Israel. We stand together with Israel, which means of course that we share also the concern about the Iranian nuclear programme. For us, any kind of nuclear option… in the hands of the Iranian government is not an option and we will not accept this (Israeli PM 2012).

This statement intertextually links terrorist and nuclear weapons with Iran, as before, and now attacks against Israel also, that were suggested in Obama’s UN General Assembly speech shown above in excerpt (35). The symbolic statement in refusing to accept the reality of Iran with a nuclear weapon made here by Westewelle can be seen in the French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius’ words in (39):

(39) According to me, we cannot accept a nuclear proliferation which can result for Iran in weaponry, and which could be used in an apocalyptic way (inforlivetvenglish 2010).

Intertextuality can be seen in the use of ‘apocalyptic’ in this example. Firstly, because this is a highly emotively-charged adjective, but secondly because this echoes Obama’s words ‘the world’s most dangerous weapons’ in (14) of Chapter 1. This hypothetical future of a threat that could harm the entire world can be intertextually linked to the British Foreign Secretary William Hague in February 2012. He said that:

(40) Clearly Iran has been increasingly involved in illegal and potentially terrorist activity in other parts of the world…. This is part of the danger Iran is currently presenting to the peace of the world (BBC News 2012d).

Again, referential aspects can be seen with mention of illegal and terrorist activity. Furthermore, Hague develops a hypothetical future without modality by stating the danger Iran poses to the world, conveying a sense of certainty in his words to the audience, as discussed in Strategy 2 of Chapter 1. This evidence in comparison to the other foreign ministers from France and Germany shows a somewhat unified stance towards Iran. Placed in the context of the ‘war on terror’ discourse these opinions may appear rational and well founded. However, this united attitude from Europe, and even the UNSC, has emerged much more recently than 2001.

A New Discoursal Practice: Other Contemporary Political Discourse

The evidence above suggests that the ‘war on terror’ discourse was operationalised by the US executive in American political institutions locally in the aftermath of 9/11, and then globally sometime afterwards. This time delay is not coincidental, as it represents the process of hegemonic struggle by the dialectical process over time. This analysis presents us with a ‘point of entry’ into the ‘social wrong’ that is an incomplete picture of the Iranian issue, which then requires a new discoursal practice to change the semiosis that ultimately shapes social practices in civil and political society. Therefore, I will present other contemporary professional voices that counter the ‘war on terror’ discourse, in an attempt to expand the semiotic capacity of the Iranian debate.

It is important to emphasise that all internationally recognised action against Iran by the US, UN, the EU and its member states has been non-military and solely focussed on sanction action, to date. The UNSC first adopted resolutions against Iran in July 2006 through Resolution 1696 but did not take any formal sanctions action against Iran until December 2006’s Resolution 1737, that restricted sales of certain weapons and nuclear technology, and froze Iranian financial assets abroad (United Nations Security Council 2006a, 2006b). The EU-wide oil embargo that David Cameron refers to in excerpt (37) was only introduced as recently as January 2012, as an addition to lower impact sanctions in June 2010 (The Iran Primer 2012, BBC News 2010). Cameron’s statements in that March 2012 joint press conference with Obama present an image of complete support for sanction efforts against Iran. However, as the time period between 2001 and UN or EU sanction action suggests, this agreement has not always been so uniform.

This can be seen in a meeting between European and American diplomats and Middle Eastern policy experts in June of 2001. In this meeting Fraser Cameron, the leader of the Political and Academic Affairs Delegation to the EU, strongly opposed sanction action against Iran. About the international legality of such action, he said:

(41) We would argue that it [the sanction plan] is counterproductive as well as against the tenets of international law (Katzman, Murphy et al. 2001).

Furthermore, he presented an argument against the instrumental rationality for sanctions:

(42) We’ve had experience of 40 years in the case of Cuba where they simply have not worked… we have looked over the years at how regimes have changed… by and large it has been through a policy of engagement (Katzman, Murphy et al. 2001).

The effectiveness of sanctions towards major change in non-liberal-democratic societies has been questioned extensively in this manner. Mark Amstutz (2008) developed a Just-Sanction doctrine in line with Just-War theory that analyses the justification for action based on seven categories of result or affect (Ridout 2012). Using this model, Scott Ridout (2012) concluded that sanctions will only have a severe effect on those in the Iranian population with little ability to pressure the government to change, due to autocratic nature of their political system. Ridout goes on to argue that targeting a state like Iran will only likely cause them to resist the sanctions. In the 2001 meeting, Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) senior fellow Richard Murphy referred to an Atlantic Council report on US-Iranian relations, which concluded that:

(43) [O]ur overall interests are not well served by over 20 years of adversarial relations. It lays out a program of action, not extremely dynamic, emphasizing – when the time is right – how to overcome obstacles to a normal relationship. Any such movement at this time obviously would not be well received in many quarters of the capital (Katzman, Murphy et al. 2001: 74).

Furthermore, no speakers in this meeting mention nuclear weapons in their professional discussion on the topic, although it is clear that by Bush’s SUA02 the linkage is firmly made.

Iran’s development or possession of nuclear weapons has been central to the debate of what action should be taken against it by the international community. Netanyahu has already called for pre-emptive air strikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities along with American policy analysts. Foremost amongst them is CFR international affairs fellow, and former US Office of the Secretary of Defense strategist, Matthew Kroenig (2012a). In a Foreign Affairs article titled ‘Time to Attack Iran’(2012b), Kroenig argues that we have ‘little choice but to attack Iran’ because it is the least bad option, and the only thing worse would be nuclear-armed Iran. His argument is that, based on International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reports, Iran is at the stage of producing a nuclear weapon within six months, and is attempting to move nuclear facilities underground where they cannot be targeted (Traynor, Borger et al. 2009, Kroenig 2012b). However, in a direct response to ‘Time to Attack Iran’, the former U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for the Middle East, Colin Kahl (2012), contradicts Kroenig’s view in ‘Not Time to Attack Iran’.

Kahl’s (2012) argument is that this six month timeframe over-exaggerates hypothetical timelines to make weapons grade uranium, let alone develop a testable device and delivery system – which could take a year for each step. In a Foreign Affairs interview with Gary Sick (2012), (member of the National Security Council under Presidents Ford, Carter, and Reagan) he puts forward the view that Iran’s nuclear weapons policy is to reach a ‘surge’ capability towards making a nuclear weapon if desired. Sick (2012) says that Iran’s policy today is no different than that of the Shah before the Iranian revolution of 1979. However, back then the policy was ignored due to friendly relations between the U.S. and Iran. He goes on to point out that we are at the point at which Iran can make a surge towards ‘the bomb’ today, and therefore ‘what we should be negotiating, is how do we negotiate it that they’re as far away from that as possible’ (Sick 2012) – in other words, ‘through a policy of engagement’ as stated by Fraser Cameron (Katzman, Murphy et al. 2001) above in (42). Therefore, Kahl (2012) argues that attacking Iran could push them towards making a surge for a nuclear weapon, despite widely quoted IAEA reports that are themselves argued to be misrepresented (Hasan 2012c).

This version of events is backed by Mark Fitzpatrick (2012), director of the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Programme at the International Institute for Strategic Studies and former Non-Proliferation advisor to the U.S. Department of State, in a Prospect magazine piece titled ‘Iran can be stopped’. Fitzpatrick (2012: 30) argues, firstly, that Iran has insufficient technological materials to build nuclear centrifuges, and, secondly, that an IAEA working paper from 2009 suggesting Iran has all the information needed to make a nuclear weapon was unvetted and unreleased, and that most of the research that informed that paper was conducted before 2004. Fitzpatrick goes on to quote a leaked US National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) from 2007, which states with confidence that Iran had stopped work on nuclear proliferation by the end of 2003. These admissions generate some enquiry into why the UN, and later EU, joint effort is only witnessed after 2006 as detailed above.

To date, the IAEA remains unable to confirm that Iran has advanced towards a nuclear weapon since 2004 (Hasan 2012a, Fitzpatrick 2012, Katzman, Murphy et al. 2001). In an interview with Al-Jazeera, Hans Blix, the former head of the IAEA and chief weapons inspector of the UN between 2000 and 2003, said with regards to his experiences in the run up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq that:

(44) The western states, and Russia and China, they could also be less menacing, less threatening; and say that, look here ‘we want a dialogue’… such as supporting Iran to get into the World Trade Organisation, supporting Iran’s civilian nuclear programme, and so forth (Al Jazeera 2012).

This again is profiting an argument for engagement with Iran, and not simply coercion through sanctions and demands. Blix goes on to discuss how the use of IAEA reports can be misleading in (45) and (46):

(45) I think you have to look into what they [IAEA] really examined. I think the IAEA receives a lot of intelligence from various countries, mostly perhaps from the US and from Israel… but then when it comes to assessing information that is given, they have to see if there is really evidence, or if it’s only information (Al Jazeera 2012).

(46) If they [the US] use it [IAEA reports] in their own advantage then they will cite them, but not otherwise (Al Jazeera 2012).

I do not believe the point needs to be laboured any further here. However, I do believe that one’s attention should be drawn back to the words I have highlighted in bold in this section as examples of discourse not normally associated with Iran in contemporary political language. If the ‘war on terror’ discourse was to take on some of these wider viewpoints it may be possible to change current social practices towards Iran and seek a different resolution.

Summary

The evidence provided in this chapter suggests that we are currently witnessing the operationalisation of the ‘war on terror’ discourse in the international institutions of Europe and Israel. This has reified the ‘Us/Them’ polarisation by presenting the debate as that of many against the sole entity of Iran. The success of this tactic can be seen through the authorisation of sanctions by the UN that began in 2006, and later the EU in 2010 – post-dating the last IAEA reports of weapons development in 2004. More specifically, this time delay suggests the process of hegemonic struggle is occurring, where orders of discourse compete through a dialectical process over time to achieve and maintain prominence over competing discourse internationally.

What is therefore of particular concern in this regard is whether the sanctions effort is merely a part of that operationalising process to legitimise action against Iran, by presenting the rational process of all possible avenues being explored – thus leading to an end state of hard kinetic action, in whatever form it may be. However, the endeavour of this chapter has been to highlight where a new discoursal practice can be engaged in the debate on Iran. This gives the opportunity to produce texts which can change the ‘war on terror’ discourse, to incorporate possibilities for engagement and cooperation, rather than coercion and conflict.

Conclusion

The evidence presented through the course of this study demonstrates the recontextualisation of semiotic discoursal elements from a ‘war on terror’ discourse – originating in George W. Bush’s January 2002 State of the Union Address – into US and international foreign policy language towards Iran – since Barack Obama’s State of the Union Address in January 2012. Subsequently, as dominant discourses subordinate and integrate competing discourses in the international arena, the ideology that forms the ‘war on terror’ discourse has been operationalised in international institutions. This operationalisation occurs at the national level, as seen in the discourse of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and UK Prime Minister David Cameron in 2012. And also at the supra-national level, as seen in the imposition of European Union sanctions against Iran since 2010, and the representation of these prevailing views in the General Assembly of the UN, along with UN sanctions since 2006. This action is despite the last IAEA confirmation of Iranian nuclear weapons development being in 2004. Furthermore, although there are wider discoursal practices available to inform our judgement of foreign policy options by our governments, the discoursal elements that these marginalised discourses proffer are seldom seen in discussions on Iran.

Competing discourses have been brought forward in this research, in line with my methodological choice to employ Norman Fairclough’s ‘dialectical-relational’ approach of CDA. This has shown how dominant discourses such as the ‘war on terror’ discourse achieve predominance by a dialectical process against competing discourses, but also how this gives new discourses an opportunity to create new texts linked to social events that can allow change to become prevalent opinions in society. This analysis has led me to concur with Fairclough’s conclusion that CDA has a dual focus both on the structure of social practices and the discoursal strategies that social agents employ to achieve ideological goals. The construction of the social practice is crucial, as this is where the ideology is most fixed, but the ‘dialectical-relational’ approach can have greatest effect by attempting to change any one of the three semiotic elements (discourse, genre, style) of a social practice. What has been demonstrated is that the strategies employed by the Bush administration after 9/11 to create the ‘war on terror’ discourse have subsequently been recontextualised towards Iran by Obama. The maintenance and reproduction of this discourse rests primarily on the construction of an ‘Us/Them’ distinction built on emotional references across numerous speech strategies used by political actors. The emotional construction of the enemy is complimented by the development of hypothetical futures and reassurance of the rationality of decision making by our governments. Together, these form powerful legitimating strategies that act to present the world as unchangeable, but fraught with possible dangers that governments have accounted for rationally, including options for the use of military force. It has been shown that these are limited policy options that are presented as though there has been a complete exploration of the available routes to policy objectives.

To date, all internationally recognised action against Iran has been in the form of sanctions. However, can it be seen that the sanctions programme is in fact a part of the hegemonic struggle between opposing discourses? If this is the case, then it can be argued that this will lead to international military action in one form or another. This would be made possible by the operationalisation of an American neo-conservative ideology through the ‘war on terror’ discourse. As Patricia Dunmire argues, this stretches back to the 1990s and calls for the neutralisation of Iran, or at least their suspected weapons programme through preventive strikes, as a perceived threat to the US. Just as 9/11 is said to have created a disjuncture in history that allowed the operationalisation of the ‘war on terror’ ideology in America, a new international social event could similarly create an opportunity for such ideology to become more widely accepted internationally. Such an example could be the intensification of the disputes over the Strait of Hormuz, which is the only oil route from the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea from producing countries in the region. Iran has frequently threatened to blockade the Strait in retaliation against international sanctions, and the US has responded by increasing patrols and military exercises in the Persian Gulf (Aboudi and Fineren 2012; BBC News 2011, 2012e). Disruption to oil routes in that region would have an impact on global oil prices, which could be used in discursive strategies by politicians to legitimise action due to the direct effect it would have on world populations.

However, this research is not complete. The first place to continue this study would be through a comparative investigation of the effect that these discursive strategies have had on public opinions of Iran across populations. Such a study should analyse data from public opinion polls over the 10 year period between 2002 and 2012, and the findings would give a better indication of the extent to which legitimation strategies win consent in society. Also, an examination of the extent to which various forms of media facilitate the transmission and reinterpretation of the ‘war on terror’ discourse should be conducted, considering the degree to which competing discourses are available in mainstream media outlets. Norman Fairclough (2010: 146) has engaged with the issue of identity construction in political television in an essay titled, ‘Ideology and identity change in political television’. Research into the opportunity that modern media channels give competing, subordinate discourses to achieve recognition has also been conducted by Innocent Chiluwa (2012). The global audience that can be reached through online forms of media, subverting and undermining official channels, is a tactic that has long been used by militant and non-violent protest groups alike to promote specific causes (Martin 2013). These channels are similarly being utilised by Iranian commentators such as New Spokesman writer Mehdi Hasan (2012), amongst many others. Mainstream political institutions, too, are increasingly using online media in an attempt to engage with a wider audience, because the visual imagery of meetings between heads of state and governments that can be conveyed here is key to translating desired issues to populations. Fairclough’s concept of ‘synthetic personalisation’ reminds us that discourse is only one part of the construction of social practices, and these visual aspects remain important to the development and reproduction of ideology in society.

Therefore, this dissertation is a starting point into the investigation of legitimating strategies towards future military action, especially in the Middle East region as vital oil resources become more sought after. It has been shown how discourses can be used in different contexts by political actors and, thereafter, how these can be accepted internationally to allow the possibility for military action, in order to meet the objectives of this research. However, the wider geo-strategic picture, in which Iran will undoubtedly play a leading regional role,must be realised seriously by world leaders – and certainly cannot be dealt with by ideological discursive practices from 2001. In this light, the public can become more aware of the ideology that is locked into political institutions and how this permeates society through the use of CDA. This will allow greater inquiry into the social practices of our governments and offer us greater options outside of conflict.

Bibliography

Amstutz, M., (2008), International Ethics: Concepts, Theories, and Cases in Global Politics,3rd edn. Lanham: Rowan & Littlefield Publication

Bednarek, M., (2006), Deliminating Evaluation. Evaluation in Media Discourse,London: Continuum

Chiluwa, I., (2012), ‘Social media networks and the discourse of resistance: A sociolinguistic CDA of Biafra online discourses’, Discourse and Society, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 217-244

Dunmire, P. L., (2009), ‘“9/11 changed everything”: an intertextual analysis of the Bush doctrine’, Discourse and Society, vol.20, no. 2, pp. 195-222

Fairclough, N., (2010), Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language,2nd edn. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited

Ferrari, F., (2007), ‘Metaphor at work in the analysis of political discourse: investigating a preventive war persuasion strategy’, Discourse and Society, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 603-625

Fitzpatrick, M., (2012), ‘Iran can be stopped’, Prospect, April, pp. 26-32

Halliday, M. A. K., and Matthiessen, C., (2004), Transivity and Voice: another interpretation. An Introduction to Functional Grammar,3rd edn. London: Arnold, pp. 280-282

Huddy, L., Khatib, N., and Capelos, T., (2002), ‘The Poll-trends: Reactions to the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001’, Public Opinion Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 418-450

Kahl, C., (2012), ‘Not Time to Attack Iran’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 91, no. 2, pp. 166-173

Katzman, K., Murphy, R., Cameron, F., Litwak, R., Sick, G., and Stauffer, T., (2001), ‘The End of Dual Containment: Iraq, Iran and Smart Sanctions’, Middle East Policy, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 71-88

Kroenig, M., (2012b), ‘Time to Attack Iran’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 91, no. 1, pp. 76-86

Lazar, A., and Lazar, M., (2004), ‘The Discourse of the New World Order: “Outcasting” the Double Face of Threat’, Discourse and Society, vol. 15, nos. 2-3, pp. 223-242

Martin, G., (2013), ‘The Information Battleground: Terrorist Violence and the Role of the Media’, Understanding Terrorism: Challenges, Perspectives and Issues, 4th edn. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 353-380

Oddo, J., (2011), ‘War legitimation discourse: Representing “Us” and “Them” in four US Presidential speeches’, Discourse and Society, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 287-314

Parsi, T., (2012), A Single Roll of the Dice: Obama’s diplomacy with Iran, London: Yale University Press

Reyes, A., (2011), ‘Strategies of legitimization in political discourse: From words to actions’, Discourse and Society, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 781-807

Reyes, A., (2008), ‘Hot and Cold War: The linguistic representation of a rational decision filter’, Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis across Disciplines, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 31-47

Van Dijk, T., (2001), Critical Discourse Analysis: Handbook of Discourse Analysis, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers

Van Leeuwn, T., (2009), ‘Discourse as the recontextualisation of social practice: a guide’, in R Wodak and M. Meyer (eds.), Methods in Critical Discourse Analysis, 2nd edn. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 144-156

Van Leeuwen, T., (2007), ‘Legitimation in discourse and communication’, Discourse & Communication, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 91-112

Van Leeuwen, T., and Wodak, R., (1999), ‘Legitimizing Immigration Control: A discourse-historical analysis’, Discourse Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 83-118

Wodak, R., (2009), ‘Critical discourse analysis: history, agenda, theory and methodology, in R Wodak and M. Meyer (eds.), Methods in Critical Discourse Analysis, 2nd edn. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 1-22

Wodak, R., and Meyer, M., (2001), ‘The Discourse-Historical Approach’, in R Wodak and M. Meyer (eds.), Methods in Critical Discourse Analysis, 2nd edn. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. London: SAGE, pp. 70-73

Wodak, R., and Pelinka, A., (2002), Discourse and Politics: The Coalition Program. The Haider Phenomenon in Austria, New Brunswick: Transaction

Online Sources

Aboudi, S., and Fineren, D., ‘U.S. allies in Gulf naval exercise as Israel, Iran face off’, [Homepage of Reuters], September 17 2012, URL: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/09/17/us-iran-nuclear-navies-idUSBRE88G0VP20120917 [March 22, 2013].

Al Jazeera, ‘Hans Blix: The Iranian Threat’, [Homepage of Al Jazeera English], March 27 2012, URL: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2012/03/2012323161458267958.html [February 4, 2013].

BBC News, ‘Iran nuclear: Israel’s Netanyahu warns on attack timing’ [Homepage of BBC News], March 9 2012a, URL: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-17316638 [May 9, 2012].

BBC News, ‘William Hague warns of Iran threat to the peace of the world’ [Homepage of BBC], January 19 2012b, URL: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-17089081 [January 31, 2013].

BBC News, ‘Strait of Hormuz closure threat to shipping’ [Homepage of BBC], February 4 2012c, URL: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-16885747 [March 22, 2013].

BBC News, ‘US and Israel tied to Flame attack by Washington Post’, [Homepage of BBC], June 20 2012d, URL: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-18517841 [February 28, 2013].