This is an excerpt from Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives – an E-IR Edited Collection. Available now on Amazon (UK, USA, Fra, Ger, Ca), in all good book stores, and via a free PDF download.

Find out more about E-IR’s range of open access books here.

The Russian leadership views mass communication as a crucial arena of global politics, in which rival powers work to undermine each other and further their own interests at others’ expense. The ability to project narratives to foreign audiences is therefore considered a matter of national security, as is the ability to control the circulation of narratives at home. In its Foreign Policy Concept of 2013, Russia declared that it must ‘create instruments for influencing how it is perceived in the world’, ‘develop its own effective means of information influence on public opinion abroad’, and ‘counteract information threats to its sovereignty and security’ (Russian Foreign Ministry, 2013). In line with these goals, the Russian government has invested heavily in media resources that can convey its point of view to other countries, such as the TV news channel RT.

Meanwhile, independent and critical voices have been increasingly stifled within Russia’s domestic media environment. State control over news on the main television channels (Pervyy Kanal, Rossiya 1, NTV) has been tight for years – all of them reflect and support the government’s stance. There is still pluralism in the press, on the radio, and on the Internet. However, the Ukraine crisis has coincided with a clampdown even in these ‘freer’ parts of Russia’s media landscape: the popular news website lenta.ru has had its editorial team replaced and the Internet and satellite channel Dozhd has been evicted from its premises.

The narratives described in this chapter can be observed throughout the Russian media which are aligned with the state – from state-owned federal channels to commercial tabloids like Komsomolskaya Pravda and the widely-used state news agency/website RIA Novosti. Some of the narratives have caused considerable consternation in Kiev. The post-Yanukovych Ukrainian government quickly banned Russian channels from Ukrainian cable networks, fearing that tendentious Russian reporting was stoking unrest in the eastern regions. It has certainly caused widespread offence in other parts of the country. Ukraine has set up a Ministry of Information in an attempt to ‘repel Russia’s media attacks’ (Interfax-Ukraine, 2014). The conflict in Ukraine has thus become an ‘information war’ as much as a conventional one. Studying Russia’s main narratives can tell us much about the ideas, fears, and goals that drive its foreign and domestic policy.

Narratives of ‘the West’, the USA and the EU

Anti-western narratives were already a salient feature of Russian political and media discourse before the crisis in Ukraine began (Smyth and Soboleva, 2014, pp. 257-275; Yablokov, 2014, pp. 622-636), but the crisis has imbued them with particular vitriol. These narratives attribute various negative characteristics to the USA and EU states via an interrelated set of plotlines that explain current developments with reference to ‘historical’ patterns. Negative narratives about the West serve the goals of the Russian leadership in a number of ways: they diminish the credibility of western criticism of Russia, they legitimise Russian behaviour in the eyes of the public, and they defend Russia’s self-identity as a European great power. At the same time, the narratives frame how Russians at all levels of society, including the elite, interpret world politics. Therefore, the fact that they are used instrumentally to bolster support for the Russian authorities should not obscure the fact that the narratives have also been internalised among those in authority and thus influence the direction of policy.

Characteristics attributed to western governments by the Russian media include hypocrisy, risibility, arrogant foolishness, and a lack of moral integrity to the point of criminality. Russian television finds evidence of these characteristics in events both past and present. At one point in summer 2014, for example, it referred back to US President Woodrow Wilson promoting democracy and self-determination ‘just for export’ while denying rights to African and Native Americans. The presenter claimed that the USA had demanded ‘the right to judge everyone by its own very flexible standards for a hundred years’ (Rossiya 1, 2014). Such claims undermine the validity of international condemnations of Russian actions in Ukraine by conveying that those doing the condemning have only their own selfish interests at heart – not any real moral values.

‘Double standards’ (dvoynyye standarty) is a charge that is levelled against the West time and time again by the Russian state media as they report and echo the words of the Russian president, foreign minister, and other officials. President Vladimir Putin, for instance, pointed out that American troops and military bases were all over the world, ‘settling the fates of other nations while thousands of kilometres from their own borders’. This makes it ‘very strange’, he argued, that the Americans should denounce Russian foreign troop deployments so much smaller than their own (Putin, 2014). Not only does such a line of argument again attack the moral standing of Russia’s critics, it also implies, through a comparison of Russian actions with ‘similar’ American actions, that Russia is just behaving as great powers do – for few doubt the USA’s great power status.

The Russian media frequently mocks western leaders and officials for their lack of understanding and for making foolish errors. When Putin gave an interview to French journalists, a Russian presenter said the president had ‘patiently and politely engaged in tackling illiteracy, as if warming up ahead of meetings with colleagues from America and Europe’ (Rossiya 1, 2014a). Sometimes the mockery is personal. US State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki became a target, with Russian television alleging that internet users had adopted the word ‘psaking’ to mean issuing categorical statements without first checking their accuracy (Rossiya 1, 2014b). The implication is clearly that condemnation of Russia originating from such sources should not be taken seriously.

The Russian media do differentiate, however, between the USA and Europe. The USA is more often accused of outright criminality. Over summer 2014, US ‘war crimes’ in Ukraine were highlighted regularly and the charges reinforced through parallels with history. In June, for instance, a Russian presenter claimed:

Ten years ago the Americans used white phosphorous against people in the Iraqi town of Fallujah. Afterwards the White House lied that it hadn’t done so… Now the USA is covering up its accomplices in the criminal deployment of incendiary ammunition in Ukraine. (Rossiya 1, 2014c)

A report about the tragic crash of flight MH17 similarly observed that there had been only a few cases of the military shooting down civilian aircraft, but the most serious had been Iranian Air flight 655, downed by the US Air Force in 1988, for which ‘America didn’t even apologise’ (Rossiya 1, 2014d).

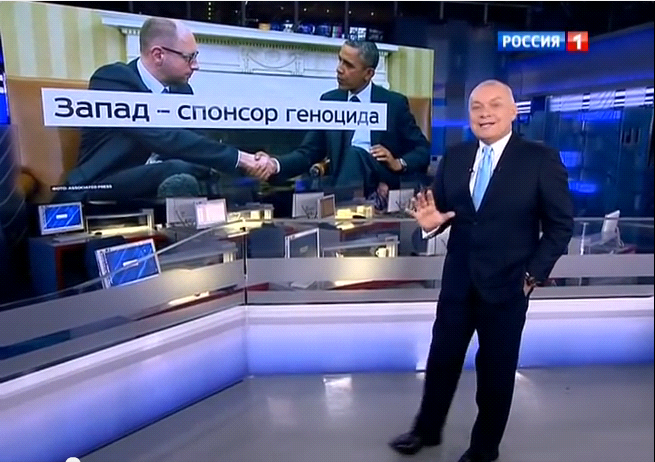

Vesti Nedeli presenter Dmitriy Kiselev interprets events against a photo of Obama and the Ukrainian Prime Minister, Arseny Yatsenyuk, captioned ‘The West – Sponsor of Genocide’.

Vesti Nedeli presenter Dmitriy Kiselev interprets events against a photo of Obama and the Ukrainian Prime Minister, Arseny Yatsenyuk, captioned ‘The West – Sponsor of Genocide’.

European states, on the other hand, were generally portrayed as being led astray against their own best interests by malign American influence. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov claimed that international attempts to ‘restrict Russia’s possibilities’ were led primarily by the USA, not the European powers; he argued that the Americans were ‘trying to prevent Russia and the EU from uniting their potentials’ due to their goal of ‘retaining global leadership’ (Lavrov, 2014). According to Russian television, the sanctions imposed on Moscow were forced through by the USA ‘to weaken the Europeans along with the Russians and get them hooked on [American] shale gas’ (Rossiya 1, 2014e). Germany and France are the countries which – in the Russian narrative – the USA is particularly desperate to prevent drawing closer to Russia. Around the anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, Russian television again drew on history to make its point, reporting:

Then, as now, Germany and Russia were acquiring strength. With their peaceful cooperation, the old world had every chance for prosperity and influence. Then, as now, the English and Americans had a common goal – to sow discord between Russia and Germany and in doing so, exhaust them. Then, as now, willingness to destroy part of the Orthodox world was used to bring Russia into a big war. Then, it was Serbia, now it is eastern Ukraine. (Rossiya 1, 2014f)

This plotline is used to suggest that Russia and Europe would enjoy a close and untroubled relationship were it not for American interference. Tensions with the EU can thus be accounted for without having to acknowledge any fundamental differences that might threaten Russia’s European sense of self.

When used strategically in an international context, narratives ‘integrate interests and goals – they articulate end states and suggest how to get there’ (Miskimmon, O’Loughlin, and Roselle, 2013, p. 5). Three dominant plotlines point particularly to the Russian leadership’s goals vis-à-vis western countries. The first relates to western ‘interference’ causing instability around the world. This plotline situates unrest and violence in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Afghanistan, Georgia, Ukraine, and elsewhere all within the same explanatory paradigm: the West (led by the USA) gets involved, then countries fall apart. The resolution proposed – either implicitly or explicitly – is for the West (above all the USA) to adopt a less interventionist foreign policy. Russia’s desire to see the USA less involved in the domestic affairs of other states relates particularly to Ukraine and the post-Soviet region, but extends similarly to parts of the world where Russia’s comfortable and profitable dealings with entrenched autocratic leaders (Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi, Bashar al-Assad) have been disrupted by American support for such leaders’ removal.

A second goal-oriented plotline relates to the West (above all the USA) seeking global dominance and acting without due consultation with others. The logical resolution to this plotline favoured by the Russian leadership is to grant non-western countries such as Russia (or perhaps, more accurately, Russia and those who agree with Russia) a greater say in international decision-making. This goal is expressed in Russian calls for ‘multipolarity’ and endorsement of formats such as BRICS and the G20.

A third major goal-oriented plotline relates to the ‘inevitable’ continuation of Russia’s cooperation with Europe. The narrative projected by Russian leaders and state media insists that commercial and business ties between Russia and the EU are continuing to develop, despite political tensions, because both sides have so much to gain from ‘pragmatic cooperation’. The end state which Russia’s leaders envisage to resolve security problems in Europe is a ‘single economic and humanitarian space from Lisbon to Vladivostok’ (a space which obviously attaches Europe to Russia while detaching it from the USA) (Putin, 2014a).

All these Russian goals are associated with the Russian state’s preferred identity as a European great power. By opposing western ‘interference’ abroad, the Russian leadership hopes to block political changes – particularly in the post-Soviet region – which might diminish the international influence which it ‘must’, as a great power, exert. By rejecting international formats in which Russia’s preferences are overridden in favour of formats where Russia’s voice is louder (e.g. BRICS), the Russian leadership is claiming the right to be heeded, which great powers ‘must’ enjoy. By pushing for greater economic cooperation with the EU and promoting the idea of a common space from Lisbon to Vladivostok, Russia is asserting its membership of Europe, while striving to minimise Europe’s ‘western-ness’ – the aspect of Europe’s identity that connects with the USA and excludes Russia.

Narratives of Russian Nationhood

The narratives by which Russia projects its position on Ukraine in the international arena are inextricably linked to the grand nation-building mission that has been underway on the domestic stage since the tail end of the El’tsyn era, and which has intensified significantly under Putin. It must be remembered that, unlike other post-Soviet nations (including Ukraine), when communism fell in 1991, Russia’s centuries-long history as the core of a larger, imperial entity ended abruptly, and it was left with no clear sense of what it was, of its ‘natural’ boundaries and basis for ‘belonging’, or of its key national myths. The fact that remnants of its former imperial conquests (including the Muslim regions of the North Caucasus) remained within its borders, and that Russia is still a vast, multi-ethnic, multi-lingual country, have not made the task of answering those questions any easier.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that the anti-westernism that has recently defined Russia’s post-Ukraine international stance, and that has recurred periodically throughout Russia’s history, has also dominated its domestic nation-building programme. Crucially, it has been at the heart of efforts to establish the basis for national belonging. This was crystallised in the extensively reported address that Putin gave to the two houses of the Russian Duma following the annexation of Crimea. One of the most striking lines of the speech made reference to ‘a fifth column… a disparate bunch of “national traitors” with which the West now appears to be threatening Russia’ (Putin, 2014b). The reference to ‘national traitors’, a term associated with the Stalin-era repressions, had a chilling effect on Russia’s now beleaguered opposition movement, but it was in keeping with the scapegoating of west-leaning liberals and other marginal groups that had been growing over the past two years. The label soon gained currency among prominent pro-Kremlin television commentators. During a special edition of the Voskresnyi vecher programme broadcast on the Rossiya channel on 21 March 2014, and in response to a question from the host, Vladimir Solovev, Dmitrii Kiselev attributed his inclusion in the list of individuals named in western sanctions against Russia to the actions of such national traitors (Kiselev, 2014).

It is commonly assumed that the anti-US and anti-European hysteria which gripped the Russian public sphere in 2014 is attributable solely to a Kremlin strategy implemented with an iron hand and from the top down. However, this is not entirely the case. First, Russia is not the Soviet Union, and certain prominent media figures linked to (but not necessarily coincident with) the Kremlin line are given the freedom to develop Kremlin thinking to extremes well beyond what might be permissible in official circles. When punitive sanctions were imposed on Russia, Kiselev was at the centre of a frenzy of cold-war rhetoric, using the platform of his Vesti nedeli programme to point out that Russia alone among nations has the capacity to turn the USA into ‘radioactive dust’ (Rossiya 1, 2014h). He was echoed by extreme right-wing writer Aleksandr Prokhanov, like Kiselev a frequent presence on Russian television, who announced that his 15-year-long dream of a return to the Cold War had been fulfilled (Barry, 2014). The two commentators, both close to Putin’s inner circle, offer a sobering demonstration of the dependency of Russian national pride in its distortive, Putinesque manifestation on the ‘treacherous, conspiratorial West’ that in the aftermath of the Ukraine crisis is Russia’s constant nemesis.

Secondly, Kremlin thinking itself is developed in part in response to, and under the influence of, ideological currents circulating at a level below that of official discourse, which employs the state-aligned media to ‘mainstream’ those currents and thus legitimate the accommodations it makes with them. In the months following the annexation of Crimea and the peak of hostilities in Eastern Ukraine, for example, the Eurasianist and extreme nationalist Aleksandr Dugin, who has been influential in shaping official discourse, once again stalked Russian talk shows. He had been somewhat sidelined prior to this and his re-emergence was an indicator of the new pathway the Russian political elite had now embarked upon. In an interview with the well-known presenter Vladimir Pozner, Dugin advocated the outright invasion of Ukraine by Russia (Dugin, 2014).

Dugin’s account of Russia as the leader of a powerful union of Slavic and Central Asian states capable of reconciling Islam and Christianity is only one of a set of core ideological narratives with which news and current affairs programmes are framed. In addition, there is the isolationist Russian nationalism[1] which rails against migration, privileging the status of ethnic Russians and showing little interest in engagement beyond Russia’s borders. This competes with an imperialist variant that is nostalgic for the Soviet Union and keen to preserve the Russian Federation as a multicultural state. Finally, a narrative[2] has emerged positing Russia as a global standard bearer for ‘traditional values’, with either an Orthodox Christian, or a dual Orthodox and Muslim, inflexion. Each carries its own brand of anti-western sentiment and each has its champions on Russian state-aligned television. The Kremlin has sometimes struggled to navigate these narratives, but in justifying Russia’s actions in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, Putin succeeded in blending several of them, bringing one or more of them to the fore for particular purposes.

The pretext for Russia’s actions in Crimea, and later for both its tacit and its explicit support for the separatist rebels in Eastern Ukraine, focused on the protection of its ‘compatriots’ (sootechestvenniki). The conflation of this term with ‘ethnic Russians’ (etnicheskie russkie) and ‘Russian speakers’ (russkoiazychnye) reflects the ethnicisation of national identity characteristic of isolationists such as Arkadii Mamontov, host of Rossiia’s Spetsialnyi correspondent show. But the ‘compatriots’ theme also had resonance for pseudo-imperialists like Prokhanov and the Eurasianist Dugin. News broadcasts, including Channel 1’s Novosti, gave sympathetic treatment to demonstrations throughout Russia and called to endorse the resistance of Russian speakers in Crimea and the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine to the new Kiev authorities. The demonstrators’ slogans and demands were quoted at length:

Russia doesn’t abandon its own’; ‘Sevastopol – we are with you’… with slogans like this the inhabitants of Petropavlovsk came to a meeting in support of their compatriots. They spoke both Russian and Ukrainian… ‘We Ukrainians are with the Russians; we are one country, one nation; we have both Ukrainian and Russian blood in us; there is no separate Ukraine and no separate Russia’… ‘The fraternal people of Ukraine are connected to us historically, culturally and by their spiritual values. Our grandfathers and great grandfathers fought together on the front and liberated our great Soviet Union. (Channel 1, 2014)

The different forms of nationalism did not always work in harmony, however, as illustrated by shifts and contradictions in coverage of the resistance of the Muslim Tatar popular to the annexation of Crimea. Some pre-annexation news broadcasts acknowledged the Tatar community’s unease about the possibility of a Russian takeover, even including open admissions that many Crimean Tatars were not pro-Russian. Later broadcasts echoed Putin’s triumphal annexation speech which insisted (against all the evidence) that most Crimean Tatars supported reunification with Russia. In this representation, the Crimean Tatars were used as a symbol of Crimea’s and Russia’s unity in diversity. This ambivalent recognition and simultaneous denial of the ‘Crimean Tatar problem’ exposed the tension between Putin’s neo-imperialist/Eurasianist variant on Russian patriotism (one which, like its nineteenth and twentieth century predecessors, aspires to square the need for inclusivity and inter-ethnic harmony with the imperative to maintain the dominant ethnic group’s power), and the isolationist nationalists, for whom ‘Muslim minorities’ constitute a problem.

The slogans quoted above were indicative of a further powerful narrative of nationhood driving Russian media responses to the consequences of regime change in Ukraine: the myth of the Great Patriotic War and the shared struggle of the Russian and Ukrainian peoples against fascism. This in turn was linked to the purported role of Nazi extremists in the Euromaidan movement and the new Ukrainian regime. Accusations that the new Kiev regime is packed with, tolerant of, or manipulated by Nazi extremists have continued to remain at the centre of Russian media accounts of the Euromaidan uprising and their efforts to discredit and de-legitimise the post-Yanukovich government and its actions. Emotive references to Banderovtsy (followers of the Ukrainian war-time Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera) abounded in the discourse not only of media commentators, but Russian political leaders including Putin himself. Pro-Kremlin outlets have consistently emphasised the role of volunteer soldiers from the right-wing Pravy sektor in prosecuting Kiev’s ‘punitive operation’ in Eastern Ukraine.

Russia’s international broadcaster, RT, links an attack on pro-Russian separatist fighters in Eastern Ukraine to the far-right political party Right Sector

Russia’s international broadcaster, RT, links an attack on pro-Russian separatist fighters in Eastern Ukraine to the far-right political party Right Sector

As recently as November 2014, the Rossiia television channel was reporting on meetings at which all elements of the Russian political mainstream recalled the shared memories of the victory against Hitler and united against the threat of Ukrainian Nazism. On 4 November, it broadcast a story about a political rally organised to coincide with Russia’s ‘Day of National Unity’ and attended by the Communist Party, the Kremlin-aligned United Russia Party, Zhirinovskii’s Liberal Democratic Party, and the social democratic Just Russia Party. All four leaders were reported to have condemned fascist extremism at the heart of the new Ukraine (Zhirinovsky, Ziuganov, and Mironov, 2014).

Finally, however, the anti-fascist agenda coexists in an uneasy relationship with the links that the Kremlin has been forging with far-right forces throughout Europe (and indeed the USA) as part of its efforts to promote Russia as the world leader of ‘traditional, conservative values’. Russia’s endorsement of the nuclear family and the Orthodox Church, its antagonism to non-standard sexualities, and its scorn for ‘politically correct’, liberal tolerance of difference have resonated with the likes of Marine Le Pen in France, Tea Party supporter Pat Buchanan in the US, and Nigel Farage’s UKIP in Britain. The visceral opposition of many of these groups to the EU, and to the entire ‘European project’, helps explain the support they have expressed for the Russian position on Ukraine and official Russian media outlets have not been slow to capitalise on this. Nigel Farage has appeared 17 times on Russia’s international television channel, RT (Russia Today), since December 2010, and his relationship with it has come under scrutiny in the UK press. But as The Guardian points out, sympathy for Russia is not limited to the margins of British politics:

Farage’s views on the EU’s role in the Ukraine are shared by some Tory Eurosceptic MPs. In a Bruges Group film on how the EU has blundered in the Ukraine, John Redwood says: “The EU seems to be flexing its words in a way that Russia finds worrying and provokes Russia into flexing its military muscles”. (Wintour and Mason, 2014)

What might seem the most paradoxical and counter-intuitive of allegiances is, in fact, just one illustration of the multiple ideological reversals and realignments that are the continuing aftermath of the collapse of communism and the ending of the Cold War.

Conclusions

One conclusion we might draw from our survey of the Russian media response to the Ukraine crisis is that Russian tactics in what some have called the ‘New Cold War’ should not be attributed to a purely cynical eclecticism (exploiting whichever political and ideological currents and trends that serve current needs, no matter what their provenance). Although such eclecticism is apparent, we should not ignore the (so far unsuccessful) efforts to knit the dominant narratives, despite all their many contradictions, into an ideological fabric capable of providing the basis for a coherent worldview and a stable sense of national identity. Nor should the notion of an all-out ‘information war’ between Russia and the West, and the way it is used to justify any manner of distortion by omission, exaggeration, or sometimes downright untruth, be seen outside the context of the residual influence of the Leninist approach to media objectivity as a ‘bourgeois construct’, or of a reaction against established values of impartiality and objectivity that extends well beyond Russia (Wintour and Mason, 2014).

However, and in a further challenge to received wisdom on Russian media coverage of Ukraine, the development of the post-Ukraine Russian world view is not an entirely top-down process and betrays the influence of powerful sub-official and popular discourses, which must be alternatively appropriated, moderated, and reconciled with one another, and with the official line. Rather than a passive tool in the Kremlin’s hands, the state-aligned media are at times serving as an active agent in managing this process.

It would be wrong, too, to explain Russia’s actions and their mediation by pro-Kremlin press and broadcasting outlets as those of an aggressive, expansionist nation determined to extend its sphere of influence into new areas. Rather, they reflect the perception of a threat to what Russia sees as its rightful status as a great power, and to its current regional interests (however distorted and misplaced we may believe those interests to be). Finally, the visceral anti-western rhetoric that dominates Russia’s public sphere to its inevitable detriment is not as undifferentiated as is often suggested; ultimately, Russia continues to harbour the desire to be seen as a European nation and as part of a continental bulwark against untrammelled American hegemony.

The correctives we propose to more reductive accounts of Russian media coverage of Ukraine do not diminish the reprehensibility of Russia’s apparent willingness to flout both international law and basic standards of objectivity in news reporting. Nonetheless, the roots of the current crisis over Ukraine cannot be fully understood without appreciating the nuances, origins, and complexities of the media narratives by which Russia attempts to legitimate its behaviour.

References:

Channel 1 (2014) television programme, ‘Novosti,’ 5 March. Available at: http://www.1tv.ru/news/social/253539.

Dugin, A. (2014) ‘Pozner,’ Channel 1, 21 April. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XEwSPzOJvaI.

Barry, E. (2014) ‘Foes of America in Russia Crave Rupture in Ties,’ New York Times, 15 March. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/world/europe/foes-of-america-in-russia-crave-rupture-in-ties.html?smid=tw-share&_r=0.

Interfax-Ukraine (2014) 1330 gmt, translated by BBC Monitoring, 6 December.

Lavrov, S. (2014) television programme, ‘Vystupleniye ministra inostrannykh del Rossii S. V. Lavrova na vstreche s chlenami Rossiyskogo soveta po mezhdunarodnym delam,’ 4 June.

Miskimmon, A., O’Loughlin, B. and Roselle, L. (2013) Strategic narratives: Communication power and the new world order. New York; London: Routledge, p. 5.

Putin V. (2014) radio interview, ‘Intervyu Vladimira Putina radio ‘Yevropa-1’ i telekanalu TF1,’ Kremlin.ru, 4 June. Available at: http://kremlin.ru/transcripts/45832.

Putin, V. (2014a) ‘Soveshchaniye poslov i postoyannykh predstaviteley Rossii,’ Kremlin.ru, 1 July. Available at: http://kremlin.ru/transcripts/46131.

Putin, V. (2014b) video, ‘Obrashchenie Prezidenta RF Vladimira Putina (polnaia versiia),’ Channel 1. Available at: http://www.1tv.ru/news/social/254389.

Rossiya 1 (2014) video,‘Vesti nedeli,’ Rossiya 1, 29 June. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=SC0tsb4MRX4.

Rossiya 1 (2014a) video,‘Vesti nedeli,’ Rossiya 1, 8 June. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFZBCeaaoB0.

Rossiya 1 (2014b) video, ‘Vesti nedeli,’ Rossiya 1, 1 June. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=48ud1pQqDWE.

Rossiya 1 (2014c) video,‘Vesti nedeli,’ Rossiya 1, 15 June. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=cY3DCjK_rdU.

Rossiya 1 (2014d) video, ‘Vesti nedeli,’ Rossiya 1, 20 July. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=_rLZaciNrQs.

Rossiya 1 (2014e) video, ‘Vesti nedeli,’ Rossiya 1, 8 June. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFZBCeaaoB0.

Rossiya 1 (2014f) video, ‘Vesti nedeli,’ Rossiya 1, 29 June. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=SC0tsb4MRX4.

Rossiya 1 (2014h) video, ‘Vesti nedeli,’ Rossiya 1, 16 March. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=utgVhoLVxsg.

Russian Foreign Ministry (2013) Kontseptsiya vneshney politiki Rossiyskoy Federatsii, 12 February. Available at: http://www.mid.ru/brp_4.nsf/0/6D84DDEDEDBF7DA644257B160051BF7F.

Kiselev, D. (2014) video, ‘Voskresnyi vecher’ Rossiya 1, 21 March. Available at: http://vk.com/video_ext.php?oid=-41821502&id=167928365&hash=1c09b7acecc4b5a2&hd=1.

Smyth, R, and Soboleva, I. (2014) ‘Looking beyond the economy: Pussy Riot and the Kremlin’s voting coalition,’ Post-Soviet Affairs, 30(4), pp. 257-275.

Wintour, P. and Mason, R. (2014) ‘Nigel Farage’s Relationship with Russian Media Comes Under Scrutiny,’ The Guardian, 31 March. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/mar/31/nigel-farage-relationship-russian-media-scrutiny.

Yablokov, I. (2014) ‘Pussy Riot as agent provocateur: conspiracy theories and the media construction of nation in Putin’s Russia,’ Nationalities Papers, 42(4), pp. 622-636.

Ziuganov, Z. and Mironov, S. (2014) video, ‘Unite Against Ukrainian Nazism,’ Vesti, Rossiia 1, 4 November. Available at: http://www.vesti.ru/doc.html?id=2098145.

[1] http://www.thenation.com/article/176956/how-russian-nationalism-fuels-race-riots

[2] http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/06/29/iraq-s-christians-see-putin-as-savior.html

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – The Myth of Being Anti-Racist and Anti-War in the Ukraine Conflict

- Opinion – War in Ukraine: Why We Should Say No to International Civil Society

- Opinion – Russian Motives in Ukraine and Western Response Options

- Opinion – Putin’s Obsession with Ukraine as a ‘Russian Land’

- Opinion – Crisis in Ukraine and High-Intensity Psychological Warfare

- Opinion – Rethinking History in Light of Ukraine’s Resistance