Do Colonial Attitudes Influence the Media’s Response to Humanitarian Crises? Western Media’s Framing of Disaster in a Post-Colonial World

“99.9% of the information you get about Africa is wrong.”

Fela Kuti[1]

“The commonest curse is to be the dupe in good faith of a collective hypocrisy that cleverly misrepresents problems, the better to legitimize the hateful solutions provided by them.”

Aimé Césaire[2]

INTRODUCTION

Although Aime Cesaire’s words were first published in 1950 in his critique of colonialism, Discours sur le colonialisme, they still have a resounding relevance to today, as does Fela Kuti’s impassioned remark at the 1978 Berlin Jazz Festival. In their respective roles as Martinician poet and pioneer of Afrobeat, their histrionic rhetoric, although overstating today’s realities, reveals the problems with Western portrayals of former-colonial territories. In the coverage of distant crises, Western media has been criticised as systematically misconstruing events and thus normalising and encouraging inadequate popular insight (Rampton & Stauber, 2003). The information provided by the media has also been cited as pivotal in both ‘altering’ publics and decision-makers to crises and influencing the foreign policy elites’ response (Soderlund & Briggs, 2008). This dissertation aims to analyse these understandings of the media’s role in and framing of humanitarian disasters, and (regretfully) hopes to establish, despite the simulacrum of increased awareness and understanding within the media, governments, international institutions and non-governmental aid organisations (Manzo, 2006), their ongoing relevance in the 21st century.

Ninety-eight percent of disaster victims each year come from the global South (Franks, 2006). This imbalance highlights a global inequality that provides the raison d’être of this project. History undeniably shapes the present. There is a direct correlation between the history of imperialism and colonialism, and European economic success and the insecurity in Africa and other parts of the world (McEwan, 2009). In order to provide the context for the study of mediatised disaster in subsequent chapters, part one will draw on neo-Marxist dependency and post-colonial theories to examine the political, economic and social structures that produce and maintain this vast disparity in a post-colonial age. Applying the insights this provides, chapter two will then explore the media’s place in Western democratic society. Academic analyses of the media’s relationship with international events and foreign policy tend to focus on conflict and war (Cottle, 2006; Herman & Chomsky, 1994; Serfaty, 1991; Soderland & Briggs, 2008; et al.). Nonetheless, as I hope to show, the insights provided by these equally apply to the media’s relationship with disasters in the South. The final section comprises my own discourse analysis of the media’s coverage of the 2011 East Africa Famine in an attempt to test the practical integrity of these theories and to argue that, despite operating in a formally post-colonial world, Western media continue to perpetuate both colonial attitudes and neo-colonial doctrine to the detriment of large portions of the globe. The food crisis that unfolded in the Horn of Africa is the most recent in the region to be declared a famine by the United Nations in a long history of similarly labelled crises, including the famine in Gode, a Somali region of Ethiopia, in 2000, the 1991/92 famine in Somalia and, earlier, the infamous Ethiopia famine of 1984/85 (UN News Centre, 2011) – the Western response and media coverage of which has received plenty of criticism throughout the succeeding decades (Franks, 2013)– and thus offers a useful juncture for analysis of the developments in reporting disaster in the global South.

The following work will primary focus on the news media. As Cottle notes, “historically and to this day, journalism remains the principle convenor and conveyor of conflict images and information” (2006: 2). Indisputably, this is the same of disaster information and images and for this reason news media takes centre stage. Of course, other institutions, such as humanitarian NGOs and aid agencies, are also due notable consideration, but as their actions can largely and increasingly be attributed to pressures of the ‘media logic’ (Cottle & Nolan, 2007), for this project they will remain as, paradoxically, both secondary to and exemplars of the news media’s influence. As this is a study of news in the global North, throughout ‘media’ will be employed in broad reference to Western news media, unless specified.

Before delving into the subsequent chapters, it is important to note and clarify the definitions of terms that are often implicit to or inform our understanding of reality. The recent contention surrounding some of these terms also highlights a promising, albeit a much prolonged, realization of the damaging effects of many well-intentioned, but ill-informed, aid and development organization’s actions.

Charles Hermann provides the most often cited definition of crisis (Soderlund & Briggs, 2008). According to Hermann, the three conditions that constitute a crisis are when a situation: “(1) threatens the high-priority goals of the decision-making unit, (2) restricts the time available before the situation is transformed, and (3) surprises the members of the decision-making unit.” (1969: 29). There are several reasons why this definition is problematic. Firstly, it suggests that a crisis is a threat to powerful players while simultaneously overlooking the real victims. As Rob Nixon highlights, far from being threatening to power elites, the slow violence – which often contributes to these humanitarian crises – suffered by the economically poor, socially insecure and politically impotent is beneficial and actively sought by these groups to advance their own agenda (Nixon, 2011). It has also been further argued that crises themselves have been encouraged, or even manufactured, in order to impose exploitative economic policies (Klein, 2007). Regardless of the extent and accuracy of these inferences, it is plain to see that crises rarely constitute any meaningful threat to the goals of the decision-making unit. Furthermore, as crises tend to be peaks in ongoing conflicts or mass political or economic insecurity, they can scarcely come as a surprise. For this reason, Soderlund and Briggs suggest “continued crisis syndrome” as a more accurate term than crisis (2008: 259). Nonetheless, for merely literary aestheticism and in keeping with the referenced literature, crisis will continue to be used throughout the following chapters, but it is hoped that the true victims and the progressive nature of crises will not be lost on the reader.

Similarly, disaster is often not an event, but a violent manifestation of long-term socio-political issues that both precede and succeed the episodic portrayal, especially of non-Western disasters, presented by the media. The two Gulf Coast hurricanes, Katrina and Stanley, that devastated New Orleans and Guatemala respectively in the autumn of 2005 each resulted in approximately one thousand deaths, but press coverage of these similar stories is markedly different. The CARMA report, an analysis of primarily European press media, found that during the 10 weeks following Katrina hitting New Orleans, over one thousand articles were written on the subject (CARMA, 2006), with newspapers still reporting on the city’s recovery and reconstruction a year later (Franks, 2006). By comparison, only 25 articles were dedicated to the unfolding disaster in Guatemala, with all but one being published within the first weeks of the hurricane striking (CARMA, 2006). Possible explanations for this disparity will be explored later, as will their implications, but for now it serves to highlight the media’s misleading ability and choice in reducing disaster to an ephemeral spectacle.

Moreover, natural disaster is a largely redundant term, as there is “no neat dichotomy between ‘man made’ and ‘natural’ disasters” (Franks, 2013: 93). Natural phenomena, such as droughts, tsunamis and earthquakes, are often a climactic or catalytic feature of social or political events where a lack of security and entitlement are the underlying factors in the development and scope of a disaster (Sen, 1981). The ratio of developed/developing world victims mentioned previously highlights the political nature of disasters. This understanding of disaster has increasingly been acknowledged and adopted by international humanitarian bodies. In 2005, the WHO chose to eliminate natural disaster from its vocabulary and has adopted ‘disasters associated with natural hazards’ in its place, because “it is widely recognized that such disasters are the result of the way individuals and societies relate to threats originating from natural hazards” (WHO). That is to say, natural hazards themselves do not usually end in the loss of lives, but spur disasters that are economic and political in origin (Middleton & O’Keefe, 1998).

A final note must be made concerning the use of ‘North’ or ‘global North’ and ‘South’ or ‘global South’ throughout this work to distinguish between the relatively wealthy continents and countries (Europe, Japan, Australia, the USA, Canada, etc.) and the relatively poor ones (Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Pacific, etc.). Although this categorisation is both geographically inaccurate and too generalised to account for complexities between and within states, it is perhaps less problematic than ‘First’ and ‘Third World’ and ‘developed’ and ‘developing’, which suggest a hierarchy and a value judgement (McEwan, 2009). ‘West’ or ‘Western’ will also be used interchangeably with the North, as this encompasses knowledge and approaches to development that originate in Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian cultures that evolved through the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and European imperialism to the present day. Aspects of this will be developed in the subsequent chapters.

CHAPTER 1 – Neo-Marxist Dependency vs. Postcolonial

The media does not operate within a vacuum. It is both formed by and informs the environment in which it functions (Cottle, 2006). This first chapter is concerned with establishing the international realm in which the media operates. To do this, I will juxtapose postcolonial theory and world-systems analysis, thereby highlighting their respective strengths and weaknesses as systems of understanding. Despite being both critical and yet, at times, complementary of one another, both ‘schools’ developed in response to the ongoing inequality following the formal decolonization of Europe’s empires in the 20th century, and thus offer a helpful framework for justifying the analysis, and aid in the understanding, of the Western world’s mediatisation of disaster.

Dependency theory, from which world-systems analysis evolved (Wallerstein, 2004), was an academic response to the unfulfilled promises of modernisation post-colonialism, specifically in relation to the formal independence, and yet uninterrupted and continued relative poverty, of Latin America in the 1950s (McEwan, 2009). The basic tenet for early, influential dependency theorists, such as Raúl Prebisch, was in noting how international trade was not between equals. Through a novel distinction between the industrial centre (or core) and the agrarian periphery, Prebisch revealed how the former are able to dominate the latter in terms of trade-relations (Love, 1980) and thereby allow surplus-value to flow from the periphery to the core (Wallerstein, 2004).

Postcolonial theory also grew in response to the pitfalls of modernisation – both its academic limitations and practical application (Kapoor, 2002), and, in a similar vein to dependency theory, serves to highlight a global imbalance through the distinction between those who were formerly the colonisers and the colonised, and its implications in the modern world. Unlike the historical materialist approach offered by dependency theory, postcolonial theory opts for an increased significance with regards to a post-structuralist perspective (Williams & Chrisman, 1994). From this perspective, the developments of recent centuries are inexplicable outside the history of colonialism, and therefore cultural domination is inextricably linked to the economic domination (Krishna, 2009) highlighted by world systems analysis. Thus, both postcolonial theory, with its emphasis on cultural domination and epistemological power, and world systems analysis, focusing more on economic power relations, are helpful for understanding the global context in which the media shapes and mediates disaster in the global South.

World-system analysis substitutes the nation-state as a unit of analysis for the study of historical systems, of which until now has only existed in three variants: minisystems, and two world-systems: world-empires and world-economies (Wallerstein: 2004). This is helpful to the understanding of international relations as it places the nation-state and similar units of analysis within the wider context in which these units perform. Minisystems equate to the self-contained, homogeneous systems of the pre-agricultural era, whereas world-empires, such as the Roman Empire, distinguished from world-economies by a political centre and lasting as the dominant system until around 1500 AD, and world-economies, which have multiple political centres or systems and in which the modern world-system can be categorized, are self-contained social systems and economic entities that don’t conform to cultural and – in world-economies’ case – political boundaries (Robinson, 2011). The essence of the distinction of systems lies in their economic organisation. Preceding world-systems analysis by several decades, Karl Polanyi notes three forms of organisation: reciprocal, redistributive and market (Polanyi, 2001), which correspond to the three systems outlined by Wallerstein. The ‘give and take’ of reciprocal organisation was utilized by minisystems, a redistributive system of accumulating goods at the top to be returned in part to the lower levels was typical of world-empires, and the market system – the monetary exchange in the public arena – is the economic organisation of world-economies (Wallerstein, 2004). Although Wallerstein notes how world-system refers to systems that are a world, as opposed to of the (whole) world, and do not usually encompass the whole globe (2004: 16), the modern world-system, with its origins in the European, expansionist, capitalist and imperial world-economy, has flourished into a ‘truly global enterprise’ (Robinson, 2011). From the perspective of world-systems analysis, the world of today is not only linked to the colonial past, but is a continuation of that same world-system, the European world-economy.

The crux of world-systems analysis, specifically in relation to the modern world-economy, is in its division of the modern globe into the core and periphery. In their application of world-systems analysis, Chase-Dunn et al. consider the core as countries with greater economic and political/military power, such as the United States, Europe and Japan, while “most countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America” are periphery countries because they are economically poorer and have weak states (Chase-Dunn, Kawano & Brewer, 2000). The core is able to exploit the periphery through structures – namely the modern world-system, the world-economy (Wallerstein, 2004) – and institutions that allow them to extract the surplus-value from the periphery. For example, the 1995 Uruguay Round – a part of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which later developed into the WTO, resulted in the strengthening of intellectual property rights, thereby preventing developing countries from producing life-saving drugs (Stiglitz, 2002). The global South is dependent on expensive medicinal goods from the global North that it is prohibited from producing in and for itself. Mohammed Berrada refers to the ‘humiliocracy’ suffered by North African states when they become complicit in this unequal relationship: in Algeria, two-thirds of its crude oil is sold to European companies, to in turn be sold back to Algeria as a refined material; in Morocco, where hundreds of graduates remain unemployed, the government employed French businesses and engineers to carry out one of its largest infrastructure projects, the Casablanca Tramway (Berrada, 2014). Not only do these examples highlight the periphery’s dependence on the core, but it also demonstrates how the relative power of the core means that the core is able to both perpetuate the status quo and increase its wealth at the expense of the periphery.

Dependency theory outlines the periphery’s economic dependency on the core, and advocates increased self-reliance through strengthened local economies and independent markets (Love, 1980), and thus is critical of the Bretton Wood institutions, especially the IMF, which profess to aid the periphery’s development largely through increased dependency. The IMF insists on client states opening up to financial market liberalization – an act that increases the unequal exchange noted by dependency theory and that benefits the core while simultaneously having a disastrous effects on the periphery. In 1993 and 1994 Kenya had fourteen banking failures as a direct result of the IMF’s insistence on financial market liberalization (Stiglitz, 2002). Furthermore, when a state refuses to follow the IMF’s demands, the IMF simply suspend their lending program, as was the case in Ethiopia in the late 1990s – often resulting in other institutions, such as the World Bank, following suit – which has obvious adverse effects on a state’s developing capabilities (Stiglitz, 2002). A World Bank report concluded that ‘adjustment programs’ carry the by-product that “people below the poverty line will probably suffer irreparable damage to health, nutrition and education” (Bourguignon et al., 1989). A further World Bank study found that fifteen African countries were economically worse off in several categories after these programs, and that recipient states performed as well as non-recipient states less than half the time (McClintock, 1994). Therefore, it is notably ironic that the IMF provides a categorization of ‘advanced economies’ on one hand, and, rather euphemistically, ‘emerging market’ and ‘developing economies’ on the other (IMF DataMapper), which is markedly similar, geographically, to the core/periphery divisions outlined by Chase-Dunn et al. This is important for the relationship between the global South and disasters, as, as previously noted, the level of devastation caused by a disaster corresponds to a state’s level of economic development. Moreover, ‘aid’ is also another means of exploitation. In a sample year, 1961, Kwame Nkrumah notes how the average sums taken out of recipient countries, from profit, interest and unequal exchange, amounted to a total of $11,800 million against $6,000 million put in. This led Nkrumah to conclude that aid is “a modern method of capital export under a more cosmetic name” (1965: 242). The core/periphery divide of world-systems analysis demonstrates the economic underdevelopment of periphery states, an exploitation resulting from the power of the core, as demonstrated by the Bretton Woods institutions, which leads to the global imbalance of large-scale disaster.

Although Chase-Dunn et al. employ a state-informed division of the core/periphery, world-systems analysis maintains that, as its name suggests, world-economies go beyond the unit-level of the nation-state (Wallerstein, 2004) in a search for the largest units of measurement that are still coherent – the world-economy (Frank & Gills, 2000). Such an approach is helpful in comprehending the reality of long-term change, as nation-states play a small role within this. This is both a strength and a weakness of world-system analysis. Its strength lies in noting how systems transcend the nation-state and thereby highlights the longevity of certain phenomena and the factors that influence both the macro- and micro-level. With this in mind, Wallerstein is able to show how the current world-system began in the sixteenth century (Wallerstein, 2004), without becoming lost in the myriad of unit-level variations and developments throughout this time. Nonetheless, this focus on one dominant institutional nexus – capitalism – fails to account for other modern transformations, such as the rise of the nation-state system (Giddens, 1994). Furthermore, as Chase-Dunn et al.’s reliance on data from individual countries demonstrates, world-system analysis’ vision is vague and difficult to study empirically. As Wallerstein professes that his model is more a mode of analysis rather than an economic or political theory (Wallerstein, 2004), this weakness is even more pertinent. He leaves the matter largely unsolved by simply noting, “[o]ne searches for the most appropriate data in function of the intellectual problem; one doesn’t choose the problem because hard, quantitative data are available” (2004: 19).

World-system analysis explains patterns of domination through capitalist development, whereas postcolonial theory is more concerned with domination through modes of representation (Kapoor, 2002). Nonetheless, in its attempt at understanding the modern world, postcolonial theory also divides the globe into two broad departments – those areas that were formerly colonisers and, more importantly, those that were formerly colonized. Arguably, this is an improvement on world-systems analysis as it offers tangible criteria for the division of the globe: those states with imperial histories or existing neocolonial policies and those who have suffered or continue to suffer under the former. Anne McClintock notes two major failings of this approach. Firstly, “the singular category ‘post-colonial’ may license too readily a panoptic tendency to view the globe within generic abstractions void of political nuance” (1994: 293). That is to say, for example, the experiences of independent Argentina and Hong Kong, with their vast differences, can in no meaningful or theoretically rigorous way share the common condition of ‘post-colonial’. Much more obviously, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia and Canada were former colonies, but their experiences of both colonization and decolonization, as break-away settler colonies, is hardly comparable to those same experiences of Algeria, Kenya or Zimbabwe, who suffered under their respective colonial powers’ brutality. There is no homogeneous ‘post-colonial’ state of being. Moreover, the dominant, colonial narratives that equate modernization with civilization and progress, can also become oppressive instruments in the hands of ex-colonized elites in the formerly colonized world (Krishna, 2009), and so the geographical demarcations must extend further to Eurocentrism in all its forms.

McClintock’s second criticism is the “prematurely celebratory” nature of ‘post-colonialism’ (1994: 294). Northern Ireland, East Timor, Palestine, Tibet and many other countries cannot be called ‘post-colonial’. The term ‘post-colonial’ fails to take into account the many places in which colonialism remains an explicit reality. Here, we can see that McClintock’s critique conflates post-colonial the term with postcolonial the theory. Postcolonial theory is concerned with recognizing how we have not yet succeeded colonialism – systems are in place that maintain an unequal international relation of cultural, economic or political power – or, rather, the theory argues that “we are not yet post-imperialist” (Williams & Chrisman, 1994). Where it would be wrong to claim we live in a post-colonial world, postcolonial theory is, at its core, concerned with exposing the continuation of colonialism in all its guises, whether it’s in literary representations (Said, 2003), or the praxis of neocolonialism (Nkrumah, 1965). While distinguishing between colonial and post-colonial Western orientalism, Edward Said notes the general continuity of the ways in which East and West are depicted (Said, 2003) and thus the sequential progress offered by post-colonialism is absent from the postcolonial theory.

This point exposes another disparity between world-systems analysis and postcolonial theory: their approach to progress. By separating the term from the theory, McClintock highlights how, despite the aims of the latter, the former is “haunted by the very figure of linear ‘development’ that it sets out to dismantle” (1994: 292). A central point to Western philosophy has been the notion of the ‘other’ to define the ‘self’. These Enlightenment binaries – self/other, man/woman, black/white, developed/undeveloped, progress/backwardness, and even core/periphery – are not objective or ineffectual, but are bound in the logics of domination and have material consequences (McEwan, 2009). During the colonial period, western thinkers were able to distinguish between the civilized, advanced cultures of the West, and the uncivilized, backward cultures of non-Europeans. Without the slightest evidential justification, linguist Friedrich Schlegel was able to conclude that Indo-Germanic languages were superior to Semitic-African languages, a reflection of their innate cultural superiority (Said, 2003). Such work “made it axiomatic by the middle of the nineteenth century that Europeans ought to always rule non-Europeans.” (Said, 1992: 75). In 1992, when President George H. W. Bush declared that US military intervention in Somalia was “doing God’s work” (Walker, 2012), we see how this sentiment has continued into the present day.

The strength and durability of Orientalism is explained by Said through Gramsci’s cultural hegemony (Said, 2003). Dennis Porter argues that it is from within this use of theory that Said fails to recognise the presence of counter-hegemonic thought throughout Western scholarly and creative writing. T.E. Lawrence is cited throughout Orientalism as an example of Western Orientalism, providing an exemplar of the ‘British vision’ of the Orient (Said, 2003: 245). Yet Porter argues that, despite being formed by a number of ideological state apparatuses – such as his upper-middle class upbringing, the Church of England, public school, Oxford and the British Army – resistance to such a hegemonic world order is present in both Lawrence’s life and texts. Lawrence’s sexuality was deviant in relation to the mainstream Christian virtues of patriarchy and the family, and is present in his passages:

We got off our camels and stretched ourselves, sat down or walked before supper to the sea and bathed by hundreds, a splashing, screaming mob of fish-like naked men of all earth’s colours. (Lawrence, 1991: 154)

Porter argues that the ‘politically Utopian idea’ and ‘homoerotic phantasm’ of this extract from Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom are unthinkable within Orientalism as defined by Said and highlights Said’s triumphalism of Orientalism, where in reality several discourses are in conflict (1994: 160). Central to this is Said’s failure to recognise the significance of hegemony as a process (Porter, 1994) and has thus been criticised as providing an “overly unifying and monolithic concept” (Kapoor, 2002).

The discourse analysis within Orientalism almost spans a century of Western literature, and yet fails to account for historical nuances (Porter, 1994). Although it is important to note, if it exists, the longevity of a certain hegemonic discourse, it is hard not to then fall into the trap of producing new forms of representation and stereotypes, such as clichés of the global South or western culture. Jan Nederveen Pieterse overcomes Said’s ahistorical Orientalism by recognising the importance of different and evolving representations of the ‘other’ in response to the relations and variations in material and cultural needs present during their specific times and places. For Europe the decisive episode in white-black relations was relations with Africa and colonialism, but for America it was slavery, and as a result the portrayals of blacks in popular culture differed. Likewise, as white-black relations evolved, so too did white images of blacks. In Europe, representations evolved from the ‘noble’, ‘good’ savage of early colonialism, with their respective aristocratic and bourgeois connotations, to the ‘childlike’ or ‘westernised’ servant/subject of mature colonialism (Pieterse, 1992: 233). On the other hand, American images of blacks underwent a ‘niggering process’ of dehumanisation and victimisation in the wake of the abolition of slave and black emancipation (Ron Dellums in Pieterse, 1992: 217). The homogenous narrative of Orientalism overlooks how images of others circulate as they reflect the concerns of the image-producers and –consumers. In short, there is no the Other just as there is no one, united or timeless We.

Postcolonialism seeks to challenge western historicism’s binaries by examining the centrality of alterity to imperialism and neocolonialism. Its emphasis on representation dismantles the Enlightenment trope of sequential progress, as civilized/backward and developed/undeveloped are revealed as idealist-biased inventions whereby “Europe constructed its identity by relegating and confining the non-Europeans to a secondary racial, cultural… status” (Tomlinson, 2005: 177). World-systems analysis, and dependency theory more broadly, also overcomes the Enlightenment’s approach to progress, albeit via a different route. By noting the dialectically contradictory structure of capitalism – the development of the core and underdevelopment of the periphery – dependency theory demonstrates how the underdevelopment of the periphery is not an early stage in a historical stage of growth, but is rather the result of the development of the capitalist world-system (Ghosh, 2001). Thus, underdeveloped states are not simply developing or undeveloped states, as the IMF would have it, but are exploited and obstructed by the economic system, and can only solve the problem of underdevelopment by breaking ties with the world-economy in which they have become enmeshed (Frank & Gills, 2000).

Both postcolonial theory and world-systems analysis recognize a global divide of the exploited and the exploiters. Both have their limitations in this respect. World-systems analysis transcends the nation-state to acknowledge wider forces, so it remains difficult to define and analyse this divide. Variations in forms of colonialism, decolonization and neocolonialism means postcolonial theory cannot simply point to a divide along colonized/colonizer lines. Although postcolonial theory attempts to overcome the binaries of western philosophy, through its critique it is instead often guilty of reinforcing them, such as the East/West divide and the linear nature of colonial/postcolonial. Nonetheless, postcolonial theory shows us that representations of otherness are informed by, and a response to, material relations. It is also clear that their main function is in establishing and maintaining social inequality. World-systems analysis’ focus on the economic system and its partition of core/periphery not only demonstrates an imbalance on a global scale, but how the system is able to perpetuate underdevelopment and inequality. Thus, we can see that “one of the most spectacular events or series of events of the twentieth century…has been the continued global spread of imperialism” (Williams & Chrisman, 1994: 1), both in its economic relations and cultural representations.

CHAPTER 2 – Mediatised Disaster

World-systems analysis and postcolonial theory highlight a global inequality as a result of the capitalist world-system and the importance of representation as a platform for domination. We have also acknowledged how disaster is merely a violent manifestation of this inequality. In light of this, the following chapter will examine the media’s representation of disaster and disaster relief by exploring the media’s framing of crises and its possible influence on public opinion and foreign policy. Although Pieterse notes how “mainstream culture is not cut from one cloth” (1992: 231), with variations in elite and popular culture, urban and rural culture, and sub- and counter-cultures, the news media nonetheless plays a leading role in the dissemination of ideas and images relating to the global South and disaster, because it is mostly through the news media that geographically distant events reach the consciousness of the Western public. Some see news content’s power in limiting and structuring audience beliefs (Herman & Chomsky, 1994), with some even claiming the media’s ability in circumventing the power of national governments (Serfaty, 1991), while others note its potential in influencing the decisions of foreign policy elites and serving as an alerting tool to unfolding crises (Soderlund et al., 2008). This chapter will examine these ideas in relation to disaster.

Although this work is concerned with representations of disaster, the first point of departure for this chapter must be in noting how little else is present in the media’s reporting on the global South. When the South is featured in the news media, a large portion of the coverage relates to conflict, war, terrorism and disaster. On television, over a third of coverage on BBC and ITN is devoted to these issues (Philo, 2002: 175). This is not only limited to domestic news. A study conducted in 2004 and 2008 found that Ugandan audiences felt CNN International’s coverage of Africa was overwhelmingly negative (Kalyango, 2011). In 1994, Media, Disaster Relief and Images of the Developing World, a collaborative report by senior officials from the BBC, CNN, Save the Children, the Red Cross and other leading media and relief organisations, noted the effects this has on Western audiences. The report found that Western audiences drastically overestimated the needs of the developing world, with respondents believing that 50 to 75 percent of the world’s children were ‘visibly malnourished’ and over 50 percent of families lived in absolute poverty. The actual figures in these cases are actually closer to 2 and 20 percent, respectively (Cate, 1994). This highlights the media’s ability in influencing levels of public understanding of the South through their agenda-setting abilities. The media’s emphasis on disaster in the South exaggerates the reality in the minds of its audience. As Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness “projects the image of Africa as ‘the other world’, the antithesis of Europe and therefore civilization” (Achebe, 2010: 3), through its selectivity, the news media is able to project an abnormal, chaotic, backward image of the global South in direct contrast to the normal, orderly and advanced North, and thus limits Western public’s understanding and perpetuates colonial attitudes.

This is part of a wider problem of Western cultural representations of the global South. A cursory glance at ‘African literature’ book cover clichés reveals a pervasive, and yet incorrect, view of the continent, where publishers’ lazy use of the acacia tree and a sunset produce a monolithic ‘Africa’ regardless of the variations in author, style, content and even geography (Ross, 2014). In his ironic short essay, How to Write about Africa, Kenyan author and journalist Binyavanga Wainaina beautifully sums up the presence of this attitude in Western literature on Africa and the disgruntlement it causes:

In your text, treat Africa as if it were one country. It is hot and dusty with rolling grasslands and huge herds of animals and tall, thin people who are starving. Or it is hot and steamy with very short people who eat primates. Don’t get bogged down with precise descriptions. Africa is big: fifty-four countries, 900 million people who are too busy starving and dying and warring and emigrating to read your book. The continent is full of deserts, jungles, highlands, savannahs and many other things, but your reader doesn’t care about all that, so keep your descriptions romantic and evocative and unparticular. (Waiwaina, 2005)

We see that even literature from within the continent, with all its sensitivity to political, geographical and social nuances, is packaged for Western audiences in this homogenizing fashion. This literary approach to the continent that Waiwaina mocks has been noted by other African writers and by academics alike (Hammond & Jablow, 1960; Mahadeo & McKinney, 2007; Achebe, 2010).

Through the focus on disaster, conflict and war, the news media’s portrayal of the global South is similarly guilty of creating a monolithic and distorted image. The effect this has on Western audiences has already been noted. One must be careful when attributing the media with power in influencing the public, but as John Street notes, “the capacity to deduce other interpretations is…dependent upon the capacity of the audience to offer an alternative account” (2001: 97). But when this alternative is beyond the scope of mainstream media in all its mediums – news, literature, films and charity campaigns – the hegemonic potential of the news media is revealed. Although part of a wider cultural phenomenon – not only in the mainstream media, but through the family, community and even formal education (Gaag & Nash, 1987) – through opting to focus disproportionately on negative events when reporting on the South, the news media contributes to the colonial trope of social binaries, with Western order and civilization on the one hand, and the South’s chaos and backwardness on the other.

In contrast to this, it could be argued that the media’s role is secondary. So far, the discussion posits the influence the media has over its audience, but the argument could equally be reversed. The media spends large amounts on researching their audience and “it is likely that they will do their best to reflect the attitudes and values of the markets they want to appeal” (Newton, 1999; 583). The media serves to reflect people’s views, not manipulate them. From this perspective, the media report disproportionately on disaster in the South to suit their audience’s preconceptions. The Image of Africa report, a collaborative effort between the UN’s FAO and various European and African NGOs conducted between 1986 and 1989, observed pervasive stereotypes of Africa throughout Europe, as well as the Western media’s exclusive use of images based on the European point of view and public expectations, noting that it is easier for the media “not to run the risk of uncertain acceptance by providing critical images corresponding to another point of view” (FAO, 1988a: 13). To take it a step further, it is a comfort for Western audiences to assert their individual and global role by relegating the South to the opposite ‘other’, just as representations of the colonial period reflected their producers’ material and psychological needs, and the modern mass media fulfills this role. Although our innate compassion and altruism should not be sidelined, the sympathy felt by audiences of disaster news is not directed towards an equal. As Pieterse asks, “are famished children and the suffering show in fundraising appeals [or news reports] really conducive to human solidarity?” (1992: 234). Whether a result of media machinations or merely a move to appease the public, it is still clear that the media normalises and reinforces this existing narrative among Western audiences through their focus on negative stories in the South, regardless of the impetus. To fully judge the integrity of this hypothesis, it is important to now turn to how the media actually frames the disasters it reports.

The BBC’s coverage of the 1984/85 Ethiopian Famine is seen as a watershed in the media’s coverage of disasters (Dodd, 2005; Manzo, 2006; Franks, 2013 & 2014). On 23 October 1984, British television audiences were presented with harrowing footage of the starving, mourning, dead and dying in Northern Ethiopia, explained to them by the authoritative voice of BBC’s Africa correspondent, Michael Buerk[3]. The emotive story generated widespread media interest throughout the West. The footage was regurgitated throughout Western television news outlets; in October, British tabloid papers dedicated 1,200 column inches to the famine in the last ten days of the month, with only fifty column inches covering the famine in the three weeks previous; and it inspired the influential Live Aid campaigns (Franks, 2013), which in turn inspired massive outpourings of monetary aid from Western audiences. The report is also cited as influencing Western foreign policy (Robinson, 2002) and adjusting popular political attitudes (Hall & Jacques, 1986).

In the footage, lasting just under eight minutes, we immediately see present the portrayals of the South critiqued by postcolonial theory: the manufacturing of colonial binaries through a decontextualised, half-clothed, starving mass of African blacks – an image so distant, if not opposite, from the mainstream Western psyche. This dichotomy of Us and Them, or the self and other, through these decontextualised images of suffering is further pronounced by its juxtaposition with Michael Buerke, a well-educated, clean-cut, white, British journalist, through whom the plight of these voiceless thousands is told. In fact, the only other voice throughout the report is from a similarly white and European doctor working for Médecins Sans Frontières in the region. Former director of communication for Oxfam, Paddy Coulter, notes how, “the rise of celebrity culture demonstrates that it may be a challenge to the British audience in relating to Africa” (Coulter in Franks, 2013: 83). Africa has come to represent so much of the other that Western audiences require a recognizable mediator to comprehend the continent. Coulter’s point is made in relation to the development of the Live/Band Aid phenomenon that grew in response to the BBC report, but we have equally see this dependence on an intermediary in news reporting and can see it in contemporary popular culture, with the continuation of charity events by Band Aid and Comic Relief and the narrating of African tragedies through such well-known celebrities as Angelina Jolie, George Clooney, U2’s Bono, Madonna and Lenny Henry, to note a few of the more prominent players.

This raises the notion concerning the importance of cultural proximity. Cultural proximity, or how relatable an event is due to audience’s identifying with the protagonists, has been noted in influencing viewer preferences (Straubhaar, 1991) and has been shown to be an important variable in how the media select and frame stories (Galtung & Ruge, 1965; Moeller, 2006; Cottle, 2013). Summed rather crudely by a Sky US correspondent, cultural proximity means that, in terms of media value, “one British person equals however many Bangladeshi etcetera” (in Cottle, 2013: 235). The 2004 East Asia tsunami provides the exemplary instance of this in action, with the CARMA report finding 40 percent of all the media’s coverage focused on westerners affected by the disaster, who made up less than one percent of the victims (Franks, 2006). The tsunami also inspired a 2012 film adaptation, The Impossible, which centres on the inconvenience the disaster caused American tourists in Thailand. Mediated through actors Ewan McGregor and Naomi Watts, the film’s portrayal of disaster has since been criticized for its many insensitivities by Western and Thai audiences alike (Cox, 2013; Rea, 2013). Although typical of the Hollywood package and process, its focus on a Western experience, its bereavement of dialogue from indigenous extras and their sole role in helping a handful of middle-class white people, and its uplifting, happy ending demonstrate the importance of cultural proximity for media audiences. This provides an explanation for the Western news media’s previously discussed unequal coverage of New Orleans and Guatamala, and may explain why disasters are so often mediated through celebrities and familiar journalists.

Another possible explanation for the media’s reliance on Western voices is simply the calculations of media logistics. BBC reporter Guy Pelham explains how reporters are drawn to places where communications are relatively easy, and that “[i]t’s relatively easy to get to places like Phuket in Thailand, where there are a number of white people who are dead or missing” (in Moeller, 2006: 178). News organisations are also largely reliant on information from official sources, such as governments and NGOs (Franks, 2010). Furthermore, it has been observed how news organisations employ a personal perspective in their coverage of complex events to increase audience engagement (Hamilton, 2005). The media were able to use this method during the 2004 tsunami, with European, Australian and American tourists in the midst of the disaster narrating the event and their stories for news reports (Moeller, 2006). This suggests that pragmatic considerations are not only given to the cultural proximity of a story, but that media judgments are dependent on the availability of information and the ease with which a perspective can be obtained and interpreted by audiences.

Nevertheless, if we look at the wider context in which this co-option of voices occurs, it reveals an unspoken hierarchy of knowledge that exceeds the media logic of cultural proximity and pragmatism. From a Foucauldian approach to genealogy, the idea of humiliocracy noted in North Africa does not just highlight the core’s exploitation of the periphery through surplus value, but reveals the implicit opinion of development strategists that Western technology and knowledge is superior to homegrown ideas. Development and relief are just as much about ideology and the production of policies and discourses as they are about flows of finance and materials through aid and investment. In light of this understanding of ideology and power, the errors of those who congratulate the influence of the 1984 BBC report and subsequent Live Aid movement on mainstream attitudes are revealed. It has been enthusiastically argued that Live Aid demonstrated, “the people can unite to save Africans from starvation…the celebration of voluntarism – the wilful resolve to take direct…non-ideological, action.” (Dayan & Katze, 1992: 21). The action and the attitudes that inform them are indeed ideological, but the hegemony of these ideologies in the North prevents them from being seen as such. The World Bank, the UN and NGOs are all identified as influential architects of development ideology, and have all been criticized for their focus on Northern agendas and silencing of indigenous knowledge and creativity (McEwan, 2009), despite the UN’s own recommendations for increased dialogue between African and European NGOs in the Image of Africa report decades earlier (FAO, 1988b). When Joseph Stiglitz resigned from his post at the World Bank, he criticized the institutions approach to development for being based solely on ideology:

There never was economic evidence in favor of capital market liberalization. There still isn’t. It increases risk and doesn’t increase growth…There isn’t the intellectual basis that you would have thought required for a major change in international rules. It was all based on ideology. (Stiglitz in Moberg, 2000)

The detrimental effects of the World Bank’s initiatives on many states in the global South make this all the more disconcerting. The UNECA calls for the ‘resource-based industrialization’ of the continent to overcome poverty (UNECA, 2013). This recommendation is informed by an assumption of linear progress: as Europe underwent the industrial revolution and prospered as a result, so too should and can Africa. Firstly, this is problematic because it once again establishes Africa as ‘backward’ when compared to the mature, and thus developed, North. More importantly, it overlooks the ‘development of underdevelopment’ noted by dependency theory (Ghosh, 2001), whereby Africa’s condition is not simply a case of being undeveloped in monetary terms, but has become underdeveloped through the world-economy’s exploitative tendencies. The title page’s cover image sums up the deep-seated colonial sentiment of the report. A word-cloud of commodities, such as cotton, oil, cobalt and coffee, form the shape of the continent. Although intended to suggest African opportunities and potential, the image and the assurance of African prosperity through UN recommendations is reminiscent of a very colonial leitmotiv:

The favourite image of the colony, in the home country, was of a place being made productive through European discipline and ingenuity, where under European management natural resources were being exploited, where order reigned so that labour could be productive. (Pieterse, 1992: 91)

Through a narrowly conceived understanding of poverty and development, international financial institutions, NGOs and intergovernmental organisations overlook alternative and less powerful voices and thereby reach forgone, often damaging, conclusions concerning development. The consequence of this has been well-documented by film maker Raoul Peck, in Fatal Assistance (2013) and journalist Jonathan Katz, in The Big Truck that Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster (2013) in their coverage of the humanitarian relief efforts in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake. The international community’s response divested Haitians of agency and failed to listen to their material and psychological needs, which, far from assisting reconstruction, amplified the crisis (Carrigan, 2014). This is not to undermine the good work and intentions of many development and relief agencies and organisations, but in a post-colonial, and not yet post-imperial, world, humanitarian interest can too easily be co-opted for power. Within relief agencies, there has been some move in the right direction. In their 2004 tsunami relief effort throughout South Asia, Muslim Aid had 160 employees working on the ground; only 2 of these were non-locals (Azad, 2014). Although the larger problem lies with Western economic and political domination and its monopoly of knowledge in development and relief initiatives, the media is guilty of normalizing this behaviour through its similarly discriminatory reporting and one-sided perspectives and thus limits the prospect of criticism or counter-views to combat the exploitation of the periphery’s economies or encourage alternative development methods and self-sufficiency.

The concept of media spheres explains this practice of limiting attitudes in the news media. Daniel Hallin divides the journalist’s world into three regions to explain their framing of events in relation to mainstream values or norms. The first region, the sphere of consensus, encompasses those views not regarded by mainstream society as controversial, and as a result the media is not compelled to present opposing views but instead serves to advocate these values (Hallin, 1989). Topics within this sphere include democracy, free speech, human rights and approaches to development, which are accepted by mainstream Western journalists and audiences as universal truths and thus disallow alternative views. But the second region, the sphere of legitimate controversy, reveals media principles as a top-down affair. This is the region of legislative debates and electoral contests, “of issues recognized as such by the major established actors” (1989: 116, my emphasis). For Hallin, this understanding is employed to explain the rise of media criticism of the Vietnam War as a result of doubt first stemming from within the US government. The final region, the sphere of deviance – those views rejected as unworthy of being heard – emphasizes this elite monopoly of values and norms. The Federal Communications Commission, the body established by US Congress to regulate communications, noted in its Fairness Doctrine, “it is not the Commission’s intention to make time available to Communists or to the Communist viewpoints” (in Hallin, 1989: 117). From this perspective, we see the media as fulfilling the role of Ideological State Apparatus, suggested by Althusser to explain the “reproduction of the relations of production” through the systemic normalisation of certain values and norms (Althusser, 1984: 22). This provides an explanation of how the media conform to the dominant Western approaches to development and disaster. Explanations of why the media conform to elite opinion have variously pointed to elite opinion within media institutions and, as noted, the media’s reliance on elite sources for information and from simply wanting to appeal to the widest audience to increase viewer- or readership.

Herman and Chomsky emphasize the importance of the profit-orientation of news organisations, where considerations of economic gain eclipse the journalistic principles of objective and informed news reporting (Herman & Chomsky, 1994). The neoliberal championing of competition within the market has resulted in the formation of large media conglomerates, with a monopoly on the dissemination of information (Gorman & McLean, 2004) that further contributes to explaining the dominance of elite voices within the media. According to elite theory, the power structure of democratic states, “involves a fusion of economic, political, and military dominants into a single power elite” (Scott, 2008: 55). Elites often share a common class background, and are likely to unite in thought and action. The wealth of large media corporations even challenges those of some small states, and in this respect do not only allow for elite expression, but are within the ambit of the elite class. This offers another factor to explain the media’s conformity to dominant ideologies.

Nonetheless, Stuart Hall and Martin Jacques argue that the 1984 BBC report was a turning point in the fortunes of the dominant ideologies of the time. They praised the Live Aid movement for its rousing of public compassion beyond the narrow nationalism of Thatcherism, and thereby shifting the political centre of gravity. Overall aid to Ethiopia went from $361 million in 1983 to $784 million in 1985 (Franks, 2013), so in terms of raising awareness and levels of unpatriotic compassion, there is no doubt that the media had a substantial effect. For Hall and Jaques, Band Aid encapsulated a “lifting of the popular horizons beyond our own shores, beyond even the boundaries of Europe, to Africa [and] thus represents a crucial turning point in the erosion of Thatcherite hegemony” (1986: 11). Despite this, it appears that UK newspapers still presented the relief effort as a patriotically British victory, with The Mirror running pieces congratulating British generosity, and The Telegraph using the opportunity to lampoon Russia’s aid efforts (Gaag & Nash, 1987).

Others were less optimistic of the campaign’s influence towards an increased humanity. Far from being a change in attitudes, the Live Aid phenomenon is merely the manifestation of hedonistic consumption and self-delusion. The movement enabled “compassion through consumption” where “[p]eople could buy the paraphernalia that denoted they cared…and watch pictures of themselves, or millions like them, caring” (Gaag & Nash, 1987: 38). It was able to package disaster with a fast, apolitical solution that appealed to people’s need for validation of their own self-worth. This approach to solidarity with suffering is an early exhibition of an ongoing transformation from an appeal based on pity to an appeal based on irony. Lilie Chouliarki argues that this is a shift from “an other-oriented morality, where doing good to others is about our common humanity and asks nothing back…[to]…the emergence of a self-orientated morality, where doing good to others is about ‘how I feel’” (2013: 3). This change can be explained through the rise of individualism as a result of consumer capitalism and the rise of public self-expression that new media has facilitated. The attitude inspired by Live Aid and the media’s representation of the South produce a narcissistic solidarity concerned with our own emotions, not the suffering of others.

What Live Aid did achieve was to flag to news editors that the public were still interested in the story. It also engendered some articles in the quality press which considered the underlying causes of the famine and suggested long term development strategies, but most articles largely remained emotive, where the themes of famine relief and victims prevailed. The press devoted huge numbers of column inches to the famine leading up to and following the Live Aid concert, and the continued level of interest merited the marking of the initial BBC report’s anniversary in 1985. But this died down by 1986, where there was only passing reference to the region in the press (Gaag & Nash, 1987). This highlights the ephemeral nature of news reports, which encourages a sporadic understanding of world events and is seen further in the media’s framing of crises. In keeping with the news values of spectacle and sensation, the media usually frame disaster in episodic terms with little engagement with the ongoing politics (Franks, 2010). Daniel Boorstin argues that this has led the media’s contribution to society’s understanding to becoming “illusionary and artificial”, with the news received by audiences having become “empty spectacle” (in McNair, 2011: 25). In his original broadcast, Michael Buerk refers to a “biblical famine”, firmly placing the disaster within a Western, Christian frame bereft of nuanced understanding. Alongside establishing the binary of our modernity and their antiquity, it implies an act of God – an inevitable or predetermined situation – and becomes apolitical, morally unambiguous and thus an unproblematic story according to the values of the news media. Disasters are largely the result of the lack of entitlements from underdevelopment, and this is especially the case for famines, which represent “a critical symbol of social and economic structures that leave people in desperate poverty, which cannot be ended without fundamental and long-term change” (O’Neill, 1986: 2), but in their simplification of news events the media overlook this critical aspect of disaster and thereby encourage an inadequate understanding, with the majority of the public attributing to the crisis in Ethiopia simply to drought (Gaag & Nash, 1987). The inequality that culminated in the long-suffering Ethiopian famine predates and continues long after the 1984-85 time frame concocted by the media and aid agencies.

The lack of thematic stories is not just limiting to audience understanding, but can also be seen as influencing government policy. Despite reinforcing colonial binaries, dominant voices and the normalisation of dependence to the benefit of Western governments and nations, the popular support for a relief effort instigated by the broadcasts pressured the Thatcher government into unenthusiastic action. Piers Robinson argues that news coverage of the Ethiopia famine is a strong example of the CNN-effect, as the policy response involved the allocation of additional funds and military logistical support (Robinson, 2002). To an extent, this is an accurate description as the UK government was well aware of the situation in Ethiopia prior to public galvanisation, but had been disinclined to do much in response. Brian Barder, then-British ambassador to Ethiopia, praises the media for enabling the government “to respond in the way that was necessary” (in Franks, 2013). But the material response reveals how the government were reacting to the media, not to the famine. In order to match the spectacle of famine portrayed in the media, the UK government provided an equally superficial spectacle in the sending of two RAF Hercules aircraft to assist the food delivery operation – a both impractical and uneconomical means of delivery (Franks, 2013). Dawit Wolde Giorgis, the coeval head of the Ethiopian Relief and Rehabilitation Commission, strongly objected to the sending of planes and provided the UK government with alternative methods of assistance that better dealt with Ethiopia’s needs, which were flatly rejected. An example of the stratification of knowledge and voices, the ineptitude of the UK government also show that “sending the RAF would do more for Britain’s public relations and domestic problems than for starving Ethiopians” (Giorgis, 1989: 193). This application of dramatic, short-term aid was part of a wider trend of the time. The Official Development Assistance’s budget for emergency relief aid went from 2 percent at the start of the 1980s to 23 percent by 1993 (Franks, 2013). Spending on long-term development was in decline, and the media’s reliance on and expectation of spectacle enabled Thatcher’s government to propel their nationalist isolationism, whilst simultaneously satisfying popular pressure.

The public pressure caused by the media was also used as an opportunity to further the national interests that Hall and Jacques previously argued to have diminished as a result of the Live Aid movement. The spectacle of the RAF wasn’t just an appeal to domestic audiences, but was also an opportunity for Britain to assert itself on the world stage. In a telegram from the UK embassy in Ethiopia, Brian Barder emphasises the importance of the RAF in outshining Soviet aid to demonstrate British cooperation and compassion to the world and the Ethiopian public in a bid to maintain Western influence in the region, noting “we have made our point by simply being there first”. This political jingoism was publicly promoted by Margaret Thatcher, who pointed out that “[y]ou see we provide help in terms of food. You can never look to Russia for that kind of food support” (both in Franks, 2013: 58; 57). Thus, we see that media interest in Ethiopia had a much weaker CNN-effect than Robinson assumes, because the media’s representation of disaster did not hinder, and arguably enabled, the realpolitik policies of the UK government. The media’s influence in alerting the government is equally dubious, as the appalling situation had been well-documented by departmental reports long before the media brought it to public light (Franks, 2013).

The media’s overwhelming focus on negative events in the South maintains the colonial binaries of our civilisation and their backwardness and creates a homogeneous ‘Africa’ in the public’s imagination. The directness of this influence on popular attitudes is not so clear-cut, as the media and the public can be seen to perpetually encourage one another’s concurrent views. It is not necessarily from within the media that these views are established, but nonetheless the media serves to reinforce and normalise them. The public’s response to a crisis is in fact a response to media’s framed information, “from selected highlights of events, issues, and problems, rather than from direct contact with the realities of foreign affairs” (Entman, 2004: 123). The can have an adverse effect on an audience’s material response, as the Live Aid movement’s unquestioning championing of unilateral aid demonstrates. Whether a consequence of dominant hegemonies or merely of media’s logistics and an appeal to the public’s need for cultural proximity, the media also reinforce the dominance of Western voices and attitudes towards relief and development at the expense of others. The media’s coverage of the 1983-95 famine in Ethiopia reveals that the media is able to increase awareness and prolong interest, but ultimately reduces disaster to transient spectacle through its decontextualisation, over-simplification and episodic framing, which in turn allows for the elite decision-making unit’s equally ineffectual and short-lived response.

CHAPTER 3 – Discourse Analysis: UK Press Coverage of the 2011 East Africa Famine

To examine the extent of the continuation of a colonial discourse in contemporary media representations of disaster, this final chapter comprises my own discourse analysis of the media’s coverage of the 2011 East Africa Famine (also known as the 2011 Horn of Africa drought). Sub-Saharan Africa contains some of the world’s areas worst hit by neo-colonialism. “With the heaviest incidence of development industry effort, sub-Saharan Africa nonetheless represents the worst-case scenario – populations whose welfare indicators decline year by year” (Bryceson & Bank, 2001: 5). Of course, IMF and World Bank apologists are pleased to point to the success stories of development programmes, such as Taiwan and South Korea (RealAid, 2011; Page, 1994, for example). But the Asian Four Tigers have had to pay the price of development, with their ecologies suffering with poisoned water, toxic soil, deforestation and dead coral seas – which all inevitably affect the poorest communities the most. “In ‘miracle’ Taiwan, an estimated 20% of the country’s farmland is polluted by industrial waste, and 30% of the rice crops contain unsafe levels of heavy metals, mercury and cadmium” (McClintock, 1994: 301). The focus on the 2011 East Africa famine also offers direct comparison with the crisis faced by Ethiopia in the 1980s. Both occurred within the same global region; both were famines – distinct from other humanitarian disasters exacerbated by natural hazards by its overtly social and political nature; and both occurred while a Conservative government was in power in the UK. In 2011, the Horn of Africa suffered the worst drought for 60 years, affecting Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia. The drought, ensuing high levels of malnutrition and large population displacement, along with continuing conflict, exacerbated physical and food insecurity in the region, with an estimated 10 million people involved in the crisis (WHO, 2011). On 20 July 2011, the UN declared famine in southern regions of Somalia, noting nearly half the population were in crisis (UN News Centre, 2011). It was the most severe food crisis in the world at the time (OCHA, 2011).

Methodology

Although the previous chapter approached the media as a homogeneous entity, this chapter will focus on the British press. As most regions of East Africa had, at some point, been under the rule of the British Empire, its portrayal in contemporary British media offers the opportunity to note the continuation of a colonial discourse in the twenty-first century. The printed media could be seen as an obsolete mode of news production in light of instantaneous, 24-hour news channels and the global capabilities of television and the Internet. Nonetheless, newspapers still command a wide readership and popularity across all sections of society. What is more, “[t]he ability of newspapers to provide political bias in an overt manner appears to provide them with a significant opportunity to rival allegedly neutral television news coverage” (Willcox, 2005: 2). Therefore, an analysis of the British press enables a comparative element. The comparison of two national newspapers provides the opportunity to reveal diversity of opinion, even counter-hegemonies, within the media. Whereas television broadcasting does little to promote the production of informed opinion from reliable sources in the news, the slower production process of the press allows for increased editorial reflection. Therefore, the analysis of the press presents a further opportunity in testing the hypotheses proposed in the previous chapters to its furthest limit by moving beyond the easily-criticised television news.

The national newspapers used in this analysis are The Guardian and The Telegraph. The Guardian is a liberal ‘quality’ broadsheet, which carries considerable comment and analysis on world events, with a daily readership of 1,027,000 (The Guardian, 2010). The Telegraph is a right-wing ‘quality’ broadsheet, which also carries extensive international news, with a readership of 1,237,000 (The Telegraph, 2014). By using two, similarly analytical, daily papers from either end of the British mainstream political spectrum, it is hoped that they reflect and represent the popular attitudes of the British public as well as the diversity within the media.

We have seen in the previous chapter that the media is guilty of reducing famine to spectacle by overlooking the underlying causes that give rise to disasters. We have also acknowledged that the unequal exchange of the world-system has resulted in the underdevelopment of the global South, and that this is a – if not the – major factor in determining the extent of a crisis. Therefore, attention will be paid to the causes of the crisis given by the papers. I will divide these into two categories, primary causes and secondary causes, to denote which cause or causes each article gives emphasis. Through it occlusion of the global interdependency, the media can be seen as serving a colonialist agenda by not noting the exploitative tendencies of neo-colonialism present in the current world-system. The causes have been categorised into the following eight groups:

- Ecological encompasses reasons given such as drought, failed rains and erratic weather, as well as contributors to these events, including climate change, global warming and La Niña.

- Neoliberalism could equally be Neocolonialism, as it includes land grabbing, the Africa Free Trade policy, large-scale commercial farming, unfair trade and decades of intervention.

- African governments includes poor planning, mis-sold food, the marginalization of pastoralist communities and bad infrastructure as a result of questionable prioritizing by East African governments. It also includes the lack of action from African states not directly involved in the crisis.

- Slow response includes failed warning systems, derisory aid contributions by European countries and the US, and G8’s broken monetary pledges.

- Conflict refers to the unrest in Somalia, although little elaboration was provided on the circumstances of the conflict in any of the articles, they did note the effect this was having on relief operations and the overall non-governance and instability of the region that exacerbated the crisis.

- Short-term solutions includes the criticism of ineffectual short-term development strategies, the lack of long-term solutions to both underdevelopment and drought, and the detrimental effects of aid dependency.

- Food prices refers to the rising global commodity prices. Although this hints at the global interdependence of states, it is separate from neoliberalism as an explicit link to this was absent in the articles.

- Overpopulation also includes high population growth. This was the only category to exclusively fall into secondary causes, and as such no elaboration was provided by either paper. As over population in the South is overestimated by the West (Cate, 1994), their unjustified inclusion of this as a cause can be seen as encouraging misconceptions of the continent.

The previous chapter also revealed the prominence of Western voices within the media, and the global inequality this hegemony perpetuates by not recognising alternative approaches to development and relief. Therefore, I will also, where possible, look at the articles’ sources of information and the actors given the opportunity to voice their views. These have been placed into six categories, although some agents within certain categories cannot be simply defined as a Western or non-Western voice:

- UN encompasses all branches of the UN, including the World Food Programme, FAO, OCHA, UNHCR and the World Bank. I have also placed Pope Benedict XVI in this category. Although their approaches to certain difficulties faced by the continent (AIDS) differ vastly, they both nonetheless represent the dominance of Western ideology, which does not warrant the pope his own category.

- UK government includes David Cameron, Andrew Mitchell and the Department of International Development.

- Aid agencies is possibly the broadest group, as it encompasses all aid agencies regardless of approaches to development, but mostly refers to members of the Disasters Emergency Committee[4]. It also includes US Mercy Corps, SOS Sahel and independent think tanks, such as the Social Science Research Council and the Overseas Development Institute.

- African governments refers to the African Union and Mohamed Elmi, Minister of State for Development of Northern Kenya and Other Arid Lands. It also includes al-Shabaab, as they controlled regions of Somalia during the crisis. Although it would be wrong to conflate these entities, they all serve to highlight the presence of non-Western voices within the media.

- Personal refers to members of the pastoralist societies who provided their own account of the crisis.

Although analysing newspaper’s coverage of a disaster, I will also note instances of positive representations of East Africa to determine how far attitudes towards the continent have changed since the 1980s.

All articles were retrieved from the LexisNexis database. The aim of this analysis is to understand the perspectives provided by these publications, therefore ‘article’ refers to all news content within the paper, including editorial and opinion pieces, leading articles, letters and news bulletins, in order to better gauge the overall character and outlook of each publication.

Findings

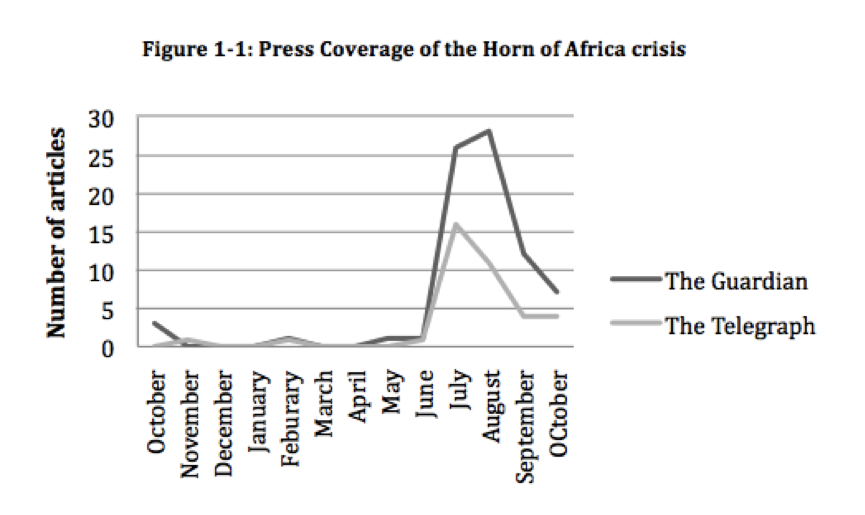

FAO warned of an impending crisis in October 2010 after the driest season recorded in 60 years. Thus, a quantitative analysis of press coverage starts from October 2010 and measures the level of coverage for the following year. Figure 1 shows how, despite warning statements given by FAO, it was not until July 2011 that the press considered the story newsworthy, with only minimal and sporadic coverage before then. This absence in the news could partly be explained by the unfolding crisis in Libya, with British military involvement and the many facets of war providing all the trappings of a good news story. Additionally, press interest coincides with UNICEF’s airlift of emergency nutrition supplies and the UN’s declaration of famine in southern regions of Somalia, which turned the unfolding crisis into a spectacle on such a scale worthy of coverage. As BBC correspondent Mark Doyle explains, “famines are sexy, predicting them is not” (in Franks, 2014).

In this case, the media can once again be seen as being limited in their alerting function. As in the 1980s, the UK government were aware of the unfolding crisis, but fortunately the contemptible wilful blindness of Thatcher was not re-enacted by the government of 2011, who had been providing “strong support for Kenya and for Somalia in the last financial year, funding emergency nutrition, health, water and sanitation and livelihood support activities through UN agencies, Red Cross and non-governmental organisations” and had also contributed additional funds to the World Food Program in light of the worsening conditions at the start of July (Mitchell, 2011).

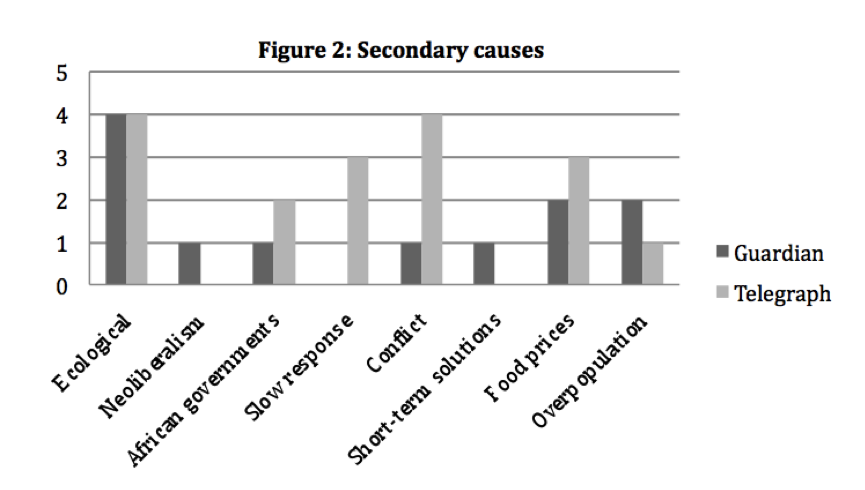

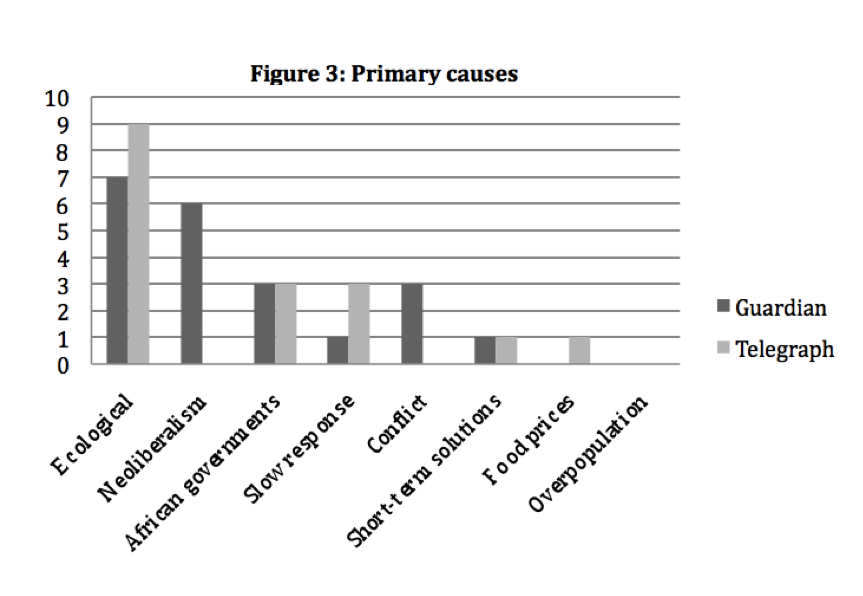

Overall, July provided the most press coverage of the crisis, and thus it serves as the sample month of the subsequent qualitative analysis. The first step of this analysis is in establishing primary and secondary causes of the crisis presented by the papers, and are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Together, these reveal a narrative distinct from that of television disaster news, as both papers provide a plethora of factors that contributed to the crisis.

Ecological factors were the most often cited cause of the crisis, scoring highest for the two publications in both primary and secondary causes. This echoes Michael Buerk’s 1984 report, and is deterministic and implies that famine is both apolitical and inevitable. Nonetheless, the high number of articles that cited drought as a secondary cause reveals that it was also considered instead as an exacerbator of other conditions, and therefore press coverage cannot be accused of oversimplifying the crisis.

Unsurprisingly for a left-leaning publication, The Guardian’s second highest ranking for primary causes was Neoliberalism, with articles noting the structural causes of the insecurities of the pastoralists and the region more generally. One article even observed the repercussions of British imperialism, the Cold War and the War on Terror on the present instability and conflict in Somalia (Lawrence, 2011). Another blamed David Cameron’s “long line of trade initiates which focus almost exclusively on boosting exports from developing countries” (Weller, 2011). The absence of these factors in The Telegraph is a consequence of their political alignment, and highlights a colonial attitude through the omission of Western accountability.

Short-term solutions was infrequently provided as a cause, and in The Telegraph, where the conclusion that “aid can inhibit growth” was provided in one article, it merely served to promote an isolationist agenda by noting the “large sums of taxpayers money” aid consumed at “a time of austerity” (Telegraph View, 2011). Nonetheless, the fact that both papers present it as a factor signifies a shift from the attitudes that pervaded the 1980s, where aid was always an unquestionable good.

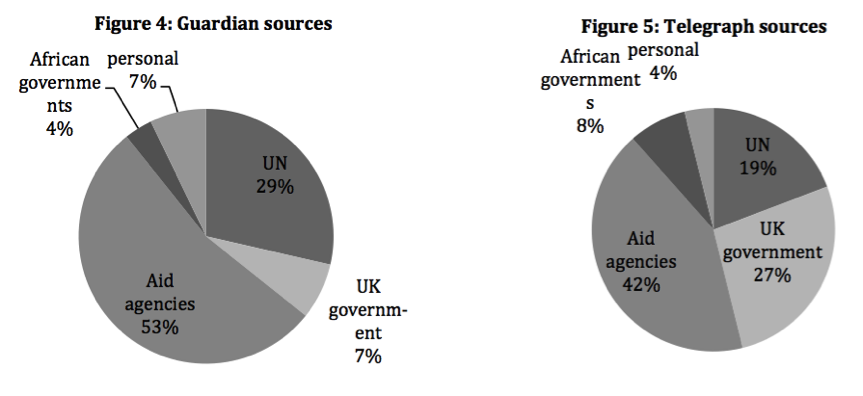

The previous chapters reveal how Western governments and Northern-led intergovernmental institutions benefit from global inequality, and how their actions serve to perpetuate it. Thus, the lion’s share, shown in Figures 4 and 5, of UN and UK government voices demonstrates how the media serves to promote the views of these bodies. The disparity between the two publication’s reliance on UK government sources echoes their political alignment. Their utilisation in The Telegraph was paradoxically, to both congratulate the Conservative government for leading the international response (Pflanz, 2011) and to criticise their enhancing of the foreign aid budget (Telegraph View, 2011). On the other hand, The Guardian, although relying on UK government sources to a far smaller extent, also employed them to praise the British public’s “great generosity” (Elliott, 2011).