British Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn shocked the British and the Western public, including his own supporters, by declaring that he would “not press the nuclear button” if he was the prime minister. Corbyn’s objections to the UK nuclear deterrent were both moral and practical: “Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction that take out millions of civilians. They didn’t do the USA much good on 9/11.” At the same time, nuclear weapons have been defended on similar moral and practical grounds as instruments that can deter the threat of a nuclear holocaust. According to the former Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Anders Fought Rasmussen, ”Ultimately, while we all hope and think it will not be necessary to use a nuclear capability, if you put in doubt whether you are willing to use the military capabilities you do have then you also undermine the strength of your deterrent.” (Ridge, 2015)

The debate on the impact of the statement on the British deterrence, as well as about the premises of the UK nuclear deterrent has been a disappointment. The roots of the logic of nuclear deterrence have not been revisited and the underlying assumptions have not been questioned. This article will visit the premises of the British nuclear deterrent and take a look at two core questions underlying the continued usefulness of the British nuclear deterrent: one related to morality, and the other related to credibility.

The Premises of Mutual Assured Destruction

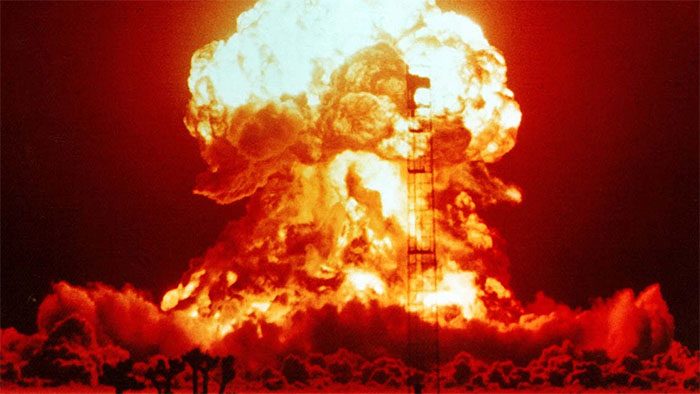

Once both the Soviet Union and the United States had managed to develop their nuclear arsenal, and especially after it became possible to launch nuclear strikes from submarines, it soon became technically impossible to defend either country against the military threat of the other. Instead of defence, therefore, both countries needed to develop capabilities to deter each others’ nuclear attacks by developing the capacity to launch a devastating second strike after surviving the enemy’s first strike. If it was not possible for either nation to wipe out each others’ military capacity by a singular nuclear attack, nuclear first strike became irrational for both, as the other could always launch a second strike that could inflict intolerable pain on the initial aggressor. According to the theory of Mutual Assured Destruction, both sides needed the capacity to hit population centers after a first strike to be able to deter the other from the first strike. This theory developed early in the 1950s and was reconstructed in the most clear and elegant manner by the US Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in his speech in 1967 (McNamara, 1967).

The British nuclear deterrent follows the logic of McNamara’s speech. The British capacity is not extensive, but it is well protected, as it can be launched from nuclear submarines that can be hidden practically anywhere in the oceans of the world. With a small force the United Kingdom cannot dream of wiping out en enemy’s military capacity, but since the force is well hidden, the country can launch a devastating second strike regardless of the force of the initial aggression by the opponent. Jeremy Corbyn is right in that the prospect of a second strike cannot safeguard the country against well hidden terrorists, who are often insensitive of deterrence (especially the suicide bombers). Yet, it can deter other nuclear states, say Russia or a future Iran, from trying to defeat the United Kingdom by using nuclear weapons.

Dilemmas of Morality and Credibility

We often assume that, since nuclear weapons are material and they can hurt us regardless of what meanings we give to them, we cannot argue against materially-based military realities. Nuclear threat is seen real regardless of whether our opponent is smart enough to understand it; nuclear safety, too, is a seen as something that comes directly from our possession of the material resources for nuclear deterrence. However, such military realities are also based on assumptions that we are able to question. The bomb is a meaningful reality only if we give it a meaning.

During the Second World War both sides used the so-called aerial bombardments, or ”morale bombing”, as a tactic against their enemies. Such tactics were also extensively used by the British Royal Air Force, and especially so from year 1942 onwards. The intention was to hit civilian centers in order to influence the leaders and the fighters of the enemy. If soldiers and decision-makers were aware of the fact that the war was destroying their homes and their families, would they not be less determined to continue such a war (Hansen, 2009)? Thus, after the war there were no difficulties in justifying a strategy that targeted civilians in order to influence and deter leaders and military elites of potential enemies. Today, since the war on terror has become the main security obsession of many Western states, undoubtedly also the United Kingdom, the idea of targeting civilians in order to influence one’s enemy has received a bad name. This is, after all, the tactic we call terrorism. Is it, therefore, ethically possible for the United Kingdom to base its strategic thinking on a doctrine of nuclear deterrence that targets civilians in order to influence the UK’s enemies? Given the ethical restrictions, is the strategy of nuclear deterrent credible even when the prime minister is someone else than Jeremy Corbyn?

In addition to moral dilemmas, nuclear deterrence also poses practical dilemmas. Is the strategy of a second strike any longer credible? During the early 1950s the Western thinking was not much concerned with the sufferings of people in the communist East. The defence of the freedom of the West was the main preoccupation of nuclear deterrence. Today, however, the world is genuinely concerned with civilians regardless of where they are. Military operations, such as the one to topple the ruthless authoritarianism of Muammar Gaddafi of Libya, or Saddam Hussain of Iraq, let alone the brutal Taliban order in Afghanistan and the Islamic State repression in Syria and Iraq, were launched to protect civilians globally.

Furthermore, we no longer believe that all rulers are concerned of the well-being of their civilians. In 2005 the United Nations accepted to the idea of the right of countries to protect civilians of other countries in case their leaders did not respect their own responsibility to protect them (International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2005). We are also talking about the right to launch humanitarian interventions to countries in which autocrats refuse to offer a humane order to their civilians (Wheeler, 2000). President George W. Bush declared in 2002 his opposition to tyrants who were indifferent towards the suffering of their own people and showed that he, and the West, were actually sensitive of the fate of ordinary people in North Korea, Iran and other tyrannies (Bush, 2002). Today, the sensitivity towards the sufferings of their people of several nuclear powers’ and states’ leaders who are aspiring nuclear weapons, such as North Korea, Russia and Iran, has been doubted. How, then, can the idea of a second strike be credible if we ourselves are more sensitive towards the civilians we threaten to kill with our second strike? Is it not like threatening to shoot one’s own foot when we threaten tyrants with a second strike?

The foundation of British strategic security requires ideas and assumptions that we can no longer be sure of. Regardless of what the opposition leader says, in the long run, nuclear deterrence seems an unconvincing foundation for the country’s security. While the material foundations might remain the same, ideas that give them meaning change, and this is a reality that was not born in the recent speech by Jeremy Corbyn.

References

Bush, G.W., 2002. State of the Union Address (January 29, 2002).

Hansen, R.S., 2009. Fire and Fury: The Allied Bombing of Germany, 1942-1945. Penguin Publishing Group, New York, NY.

International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2005. Responsibility to Protect Report [WWW Document]. Counc. Foreign Relat. URL http://www.cfr.org/humanitarian-intervention/international-commission-intervention-state-sovereignty-responsibility-protect-report/p24228 (accessed 10.31.13).

McNamara, R., 1967. “Mutual Deterrence” Speech by Sec. of Defense Robert McNamara, San Francisco, September 18, 1967.

Ridge, S., 2015. Corbyn: Nukes “Didn”t Do USA Much Good On 9/11’. Sky News.

Wheeler, N.J., 2000. Saving strangers. Humanitarian Intervention in International Society. Oxford University Press, New York.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Brexit and Arms Sales to the Philippines: A Reactive Approach to Human Rights

- The Nuclear Taboo and the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons

- ‘Press the Reset Button:’ Right-Wing Extremism in Germany’s Military

- Towards Advocating a ‘Tradition Approach’ to Gandhian Nuclear Ethics

- Saving Grace or Achilles Heel? The Odd Relationship Between Nuclear Weapons and Neo-Realism

- Option WTO to Assist Nuclear Nonproliferation – With Minuses and Pluses