An unyielding belief that all people yearn for certain things: the ability to speak your mind and have a say in how you are governed; confidence in the rule of law and the equal administration of justice; government that is transparent and doesn’t steal from the people; the freedom to live as you choose. These are not just American ideas; they are human rights. And that is why we will support them everywhere. President Barack Obama[1]

The Libyan rebellion afforded lasting perceptions into the global balance of power and a reaffirmation of the West’s need to promote human rights as was recounted by President Obama in 2009, during his visit to Cairo. The president drew from the Qu’ran, the Talmud and the Bible in his effort at speaking the truth on United States’ (U.S.) relations with the Muslim world; what some called soft diplomacy, while others called it the “beginning of a new American policy” (Holzman 2009). Barely two years following the President’s visit, violent unrests escalated in some parts of the Muslim world, in what came to be termed the Arab Spring uprisings. The Libyan crisis which commenced February 2011[2] has been associated with the Arab Spring uprisings of the Middle East (the Libyan unrest began after two similar uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt in 2010), and it received massive attention from the international community who demanded that a humanitarian intervention be initiated in order to protect civilians on the ground.[3]

Brief Background

The Libyan crisis came as a surprise to several onlookers, who later attributed its success to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) involvement.[4] Military intervention in Libya began with French military operations in the region in March 2011. While France’s operation in Libya was the second since 1962, this was NATO’s first military involvement in North Africa. Humanitarian reasons and the need to protect civilians were the pivotal justifications of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and NATO for necessitating Operation Unified Protector (OUP).[5]

OUP was a United Nation’s (UN) sanctioned military operation, issued under Resolution 1973 under Chapter VII of the United Nations (UN) charter, on March 17, 2011. This resolution authorized the use of force and the establishment of a no-fly zone over key cities aimed at protecting civilians from the Qaddafi regime.[6] The enforcement of this resolution required the establishment and operation of military air bases close to the Libyan coast. This humanitarian mission was run from JFC-Naples, which was one of NATO’S three operational commands at the time. JFC-Naples was created in 1950 following the outbreak of the Korean crisis as the Allied Forces Southern Region (AFSOUTH). At conception, Greece and Turkey were not part of the Southern region, therefore, AFSOUTH only had leverage over a portion of the Mediterranean until 1952 when the aforementioned countries were both admitted as member states, after which the coalition was put in charge of the entire Mediterranean region.

Gertler (2011) states that the first offensive operations were launched by French aircrafts striking armored units near Benghazi. The operation was facilitated by an attack on Libyan air-defense and other military targets using “110 Tomahawk cruise missiles fired from both US and British ships and submarines struck more than 20 integrated air defense systems and other air defense facilities ashore.”[7] Additionally, British aircraft (Tornado GR4) soaring from the Royal Air Force base at Marham, England, reportedly engaged Storm Shadow cruise missiles.[8] The no-fly zone eventually covered the Libyan coastline by March 23, 2011 including Tripoli.[9] Invasive military operations were under way to counter the Libyan ground armed forces who were seen as posing a threat to the civilian populace, but there was “no indication that Gadhafi’s forces [were] pulling back from Misurata or Ajdabiya.”[10] On March 28, 2011, the department of defense (DOD) declared that A-10 and AC-130 aircrafts had begun military operations over Libya on March 26, 2011. The A-10 is enhanced to destroy armored vehicles, while the AC-130 offers close air support and interdiction (Jeremiah Gertler March 2011). According to Vice Admiral Bill Gortney, U.S. ability to defeat the regime’s ground forces was increased with the introduction of these weapons.[11]

A summary of NATO’s engagement in Libya could potentially signify that the alliance had been active in the region since its formation. In actuality, NATO exhibited a quiescent attitude towards the MENA region until after the 9/11 attacks on the U.S., when it increasingly became involved with the region, in its fight against terror. According to Gaub (2012), the expansion of the Mediterranean Dialogue seemed a positive platform for cooperation between the alliance and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region in the war on terror, these relations were extended to (if not amplified in) 2010, with the commencement of the Arab Spring.

Comparative Development of the Crisis and International Response

When likened with the humanitarian response given to other countries that suffered (or are suffering) civil unrest, such as the Syria, it becomes obvious that the purpose and consequence of the diplomatic community that partook in the coalition against Qaddafi was astounding and exceptional. While Qaddafi loyalists were attacked only thirty-two days after the first protest began in Benghazi;[12] Syrian president Bashar al-Assad sought to suppress the ongoing revolt in Syria since March 15th 2011 (UNHCR 2013).[13] The Syrian case, for instance, is one of the most attention-grabbing political insurgencies in the study of contemporary mass mobilizations. The varying response to both cases is almost unfathomable at first appearance. The demonstration in Syria pressed for rights comparable to those that were demanded in 2011 Libya. These demands were centered on the needs of a younger population: a more democratic state, an end to corrupt practices (a more transparent government), and an improved standard of living.[14] The Syrian and Libyan cases erupted in the Middle East around the same time, but received very distinct responses from the international community. This type of selective treatment often creates an imbalance in international law, and it is for this purpose that this paper seeks to unravel the reasons why the decision-making process sanctioning a military intervention into Libya was quick and subsequently transformed in its mission to open war against Col. Qaddafi.

Table 1

| Uprisings | Date of Uprising | United Nations Resolution | Date Resolution was passed |

| Bahraini Uprising | February 14, 2011 | None | |

| Kosovo Crisis | February 28, 1998 | UNSCR 1160, 1199, 1203, 1239, and 1244. | March 31, 1998; September 23, 1998; October 24, 1998; May 14, 1999; June 10, 1999 respectively. |

| Libyan Crisis | February 17, 2011 | UNSCR 1970 and 1973 | February 26, and March 17, 2011 respectively |

| Rwandan Genocide | April 6, 1994 | The SC authorized the deployment of French troops into the South of Rwanda to protect the refugees. | June 22, 1994 |

| Syrian Crisis | March 13, 2011 | In February 2012, the Council attempted to pass a resolution calling for a military intervention into Syria, but the resolution was stalled by China and Russia who vetoed. | February 2012 |

| Yemeni Uprising | January 27, 2011 | Resolution 2014. This resolution advocated a Yemeni-led political appeasement process | October 21, 2011. |

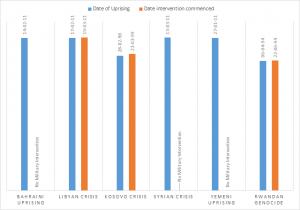

Chart 1:

Uprisings and Crises

Table 1 above indicates the beginning of various uprisings, the date the international community passed a resolution sanctioning military intervention for humanitarian purposes, and the name of the resolutions. Going by this table, one can see that, the transatlantic community launched an illegal humanitarian intervention into Kosovo in 1999,[15] but did not repeat such actions in Syria even though biological weapons were used on the civilian population. Meanwhile, in Yemen, the international community refrained from enforcing any resolutions until 10 months into the crisis. Chart 1 indicates the time lapse between various uprisings and the day an actual military intervention commenced. The chart shows that the Libyan crisis received the fastest military response of all the crises in the chart. As has been demonstrated, the Rwandan case posed a bigger threat than the Libyan crisis, yet the Council went about administering armed relief with indifference. The Bahraini uprising was squashed with tear gas[16] and Saudi Arabian military repression, but a peace-deal for a permanent cease-fire was not imposed, as such the uprising is technically still ongoing.[17]

The legal status of humanitarian intervention also is an important factor in this project, as it has been the subject of major criticism from scholars who do not consider the UNSC-sanctioned intervention into Libya as having legitimacy. Countless arguments have been advanced toward the irrelevancy of NATO’s mission, ranging from Prashad (2012), who argues that the mission was not guided by any ethical responsibility, to Gaub (2012, and 2013) who has mentioned in two separate articles that the premise of the mission was unclear. These scholarly opinions help in building the arguments I raise in this paper, especially the reasons I advance for why OUP was hasty and eventually transformed from its initial prescription of ensuring civilian protection. Before OUP had run its course, certain political figures such as President Jacob Zuma of South Africa and Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov openly criticized the mission. They argued that it had been orchestrated with such rapidity that the end goal of the mission had gotten mixed up with the beginning aim, and the United Nation Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1973’s call for civilian protection had been transformed to mean regime change (Vandewalle 2012).

The Right to Protect

The notion of R2P and what defines a humanitarian mission has been subject to considerable debate throughout the years in scholarly literature; regardless, the concept itself is precisely defined by Holzgrefe as:

The threat or use of force across state borders by a state (or group of states) aimed at preventing or ending widespread and grave violations of the fundamental human rights of individuals other than its own citizens without the permission of the state within whose territory force is applied. (Holzgrefe 2003)

The mention of action taken by a ‘group of states’ is predominantly applicable to NATO, as the operation against Libya was conducted by a group of states[32] upon receiving authorization to intervene from the United Nations Security Council. They were therefore acting within the framework of ‘traditional’ international law.

Ethnographers have attempted to classify humanitarian interventions under humanitarianism; Fassin (2012) states that “moral sentiments have become an essential force in contemporary politics: they nourish its discourses and legitimize its practices…the emotions that direct our attention to the suffering of others and make us want to remedy them.” In other words, French authorities who granted residence to immigrants on the grounds of humanitarian reasons, and western heads of state who called for the bombing of Kosovo both speak the same language of humanitarianism. An urgent need for a rehabilitated appraisal of key terms such as: human rights, military humanism/humanitarian intervention, and humanitarianism, therefore becomes fundamental in this regard. There is a noteworthy distinction between humanitarianism and human rights–according to Wilson and Brown (2009)–human rights are pre-existing legal protections of individuals; whereas, humanitarian action by states is often justified less by a legal action as opposed to a moral one.[33] This is in part because humanitarianism is less firmly grounded in international law than in human rights. Human rights and humanitarianism share similar concepts of welfare and dignity yet vary in their definitions. The term humanitarianism has been traced back to 1859 by Barnett (2013), a term that according to him has become about shared moral and political values. Therefore, the absence of human rights in a state, justifies a humanitarian intervention. Human rights was the missing variable that, according to President Obama, spurred the Arab Spring “square by square, town by town, country by country, the people have risen up to demand their basic human rights.”[34]

Finnemore (1996) further argues in a theoretical essay that humanitarian interventions have changed over the years, and the definition of who qualifies as human and deserving of protection by foreign states has evolved over time to embody a more inclusive outlook. By the start of the 20th century, all human beings were deemed equally deserving of assistance and protection from human rights violations. Norms about multilateral action were equally strengthened, rendering multilateralism not just attractive, but imperative for states to accept as political, normative, legitimate and genuine, but not strategic. These arguments while intelligible, do not take into consideration the argument that humanitarian interventions are not always typically driven by R2P nor are they typically grounded in a moral compass.

The justification of an armed intervention in cases of an impending massacre aimed at the restoration of human rights is widely accepted in 21st century scholarship. In the words of Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, “the defense of human rights is a form of mission” (Cohen 1999). Along the same path, Chandler (2011), argues that humanitarian intervention was lauded in the 1990s by academic commentators as heralding a new global order of multicultural law and human rights. Bernard Kouchner, the cofounder of Médecins sans Frontières (MSF), maintained that the right to intervene to protect endangered individuals in extreme circumstances and coercive policies is indispensable.[35] Interpreting the acceptable method of intervention, its context and just definition (what qualifies or does not qualify as a humanitarian intervention) is however, still mostly controversial. Scholars such as Pieterse (1997) are largely pitted against the notion of humanitarian intervention in its contemporary form. He holds that it “reinforces authoritarianism, hard sovereignty, and militarization” (Pieterse 1997). Pieterse’s observation ties in neatly with a sentence from Fassin’s (2012) preface that the humanitarian’s passion most definitely raised suspicion of the pursuit of goals other than pure benevolence toward a nation that was sequentially “oppressed by the former and exploited by the latter.” Along the same line reasoning, Michael Walzer (1992) states that interventions are usually unattractive and inspired by imperial desires, thereby rendering them unjustifiable, regardless of their final goal. In which case, critics have argued humanitarian interventions are incomplete especially when debased with selfish ends. All these arguments while logical, are lacking in content, as they do not discuss the sufficient conditions necessary to authorize a military humanitarian intervention. In other words, they fail to discuss why certain interventions are treated with urgency, but not others. Take the “bush wars” in the Central African Republic (CAR) for instance. In-fighting has been tearing the CAR apart since 2003, yet very little has been done by the international community in putting an end to these wars, which have led to major displacements, refugee crisis and poverty.

The formal legal limitations of the Right to Protect (R2P) and the apparent requirement of the Security Council’s (UNSC) authorization have resulted in a justification of intervention as was expressed by Kofi Annan, “if humanitarian intervention is, indeed, an unacceptable assault on sovereignty, how should we respond to a Rwanda, to a Srebrenica–to gross and systematic violations of human rights that offend every precept of our common humanity?” (UN 2000). Meaning, the Libyan case was the “prospect of a ‘second Srebrenica’ or even ‘another Rwanda’ in Benghazi were Qaddafi allowed to retake the city that forced the ‘international community’ (minus Russia, China, India, Brazil, Germany, Turkey et al) to act” (Hugh Roberts, 2011). This is an acceptable argument, whose flaw lies in assumptions and case comparisons. Just as Roberts (2011) goes on to state, there was no evidence that once Qaddafi’s forces retook Benghazi, they would be ordered to embark on a general massacre. Moreover, Rwanda was an extreme case of ethnic cleansing, while the Libyan revolution was a call for socio-economic and political rehabilitation that eventually resulted in a transatlantic response barely a month after in-fighting had commenced. Qaddafi’s forces had committed massacres and crimes against humanity, but it was nothing remotely similar to the slaughter at Srebrenica or the bloodbath witnessed in Rwanda in 1994.

On the other side, advocates of the Libyan intervention such as, Pattison (2011) maintain that there was adequate Just Cause to warrant NATO’s operation in Libya. His argument abides by the Just Cause theory in the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) 2001 report, which states that there is need of an intervention abroad where there is “large scale loss of life, actual or apprehended, with genocidal intent or not, which is the product either of deliberate state action, or state neglect or inability to act, or a failed state situation; or large scale ‘ethnic cleansing’, actual or apprehended, whether carried out by killing, forced expulsion, acts of terror or rape” (ICISS 2001). In spite of Pattison’s acceptance of OUP as morally admissible, he recommends a “more morally defensible test” (Pattison 2011), to evade a case-by-case comparison on normative pointers and moral principles. Pattison’s attempt to define a compulsory scale for intervention directly ties in with the question of justification (for humanitarian interventions). As Griffith argues, “moral judgment is not calculation or deduction” (Griffith 1958) and it relies on a moral and ethical authority. A debate on the permissibility of an armed intervention spontaneously takes us back to the ethical discussion. The whole discussion about morality, pathos, ethical standards, obligation, and justifications for intervention or non-intervention are grounded in the determination and capability of a government to react.[36] Therefore, national politics guided by realpolitik and geo-strategic interests hold the most important potion of the debate regarding military humanitarian intervention. Griffith’s views are thereby seemingly rational. A permanent standard for an essential military intervention could theoretically streamline any conversation when a civil unrest commences abroad.

In March 2011, according to western media and public opinion,[37] OUP was deemed a justified humanitarian intervention. However, an increasing number of scholars deny this assessment, such as, Bush, Martiniello, and Mercer arguing that “Imperialist intervention uses the language of humanitarianism to justify its use of force…” (Bush et al 2011). Critics of the Libyan intervention such as Bello (August 2011), Prashad (2012) and Forte (2012), have further argued that NATO runs the risk of being reduced to an armed service provider for the imperial powers–backing efforts to oust Qaddafi (a quasi-allied dictator). Roth (2004), in line with Forte’s arguments, expresses dissatisfaction with the 21st century notion of humanitarian intervention, stating that:

Only large-scale murder, we believe, can justify the death, destruction, and disorder that so often are inherent in war and its aftermath. Other forms of tyranny are deplorable and worth working intensively to end, but they do not in our view rise to the level that would justify the extraordinary response of military force…The capacity to use military force is finite. Encouraging military action to meet lesser abuses may mean a lack of capacity to intervene when atrocities are most severe. The invasion of a country especially without the approval of the U.N. Security Council, also damages the international legal order which itself is important to protect rights. For these reasons, we believe that humanitarian intervention should be reserved for situations involving mass killings. (Roth 2004)[38]

To them, it came across like NATO was bombing Libya because it could and was sure of getting positive effects. That job description is a long way from what NATO still insists is its core, founding mission: to protect its members’ territory and population (doctrine of flexible response). As a matter of fact, the Libyan revolution was not posing a security threat to any neighboring states or to any of the member states of the Arab League,[39] leading the validity of these arguments back to the ethical discourse of the mission.

Counter arguments to the credibility of the moral viewpoint of military humanitarianism have been further posited by Gibbs (2009) and Chomsky (2002). Their books are both strongly worded arguments against U.S. foreign policy and NATO’s humanitarian intervention in the Balkan region in 1999. In lieu of abstracts, Gibbs’ (2009) book attempts a balance in humanitarian intervention, stating that the attacks on Serbia were misplaced and in no form supported the humanitarian foundation. In a similar light, Chomsky (2002) condemns the 1999 NATO attacks in Serbia (that were geared toward bringing an end to the ethnic cleansing in the Balkan region), referring to them as the “new humanism.” The first take away from these readings is how the Euro-Atlantic community performed the same crime they were accusing the Serbs of committing in 1999. Theirs was, however, termed a humanitarian intervention with military action embarked upon in response “to only certain kinds of moral concerns, such as protecting the welfare of some groups of people, where this involves preventing genocide, or preventing mass expulsions” (Chatterjee and Schied 2003). These arguments are however jarringly firm, and indicate the imbalance in international law.

The political viewpoint of humanitarian interventions contains a large variety of opinions. National interests play an important role and are used as a main argument against interventions: “the Obama administration had initially proven highly reluctant to enter the fray, arguing that the United States had no real national interests in Libya” (Vandewalle 2012). Statements of politicians can powerfully underline attitudes in relation to humanitarian interventions. At the beginning of the recently ended operation in Libya, one U.S. politician concluded that “it is doubtful that U.S. interests would be served by imposing a no-fly zone over Libya” (Blanchard 2011). Valentino (2011) in the same light notes that: “humanitarian interventions have won the country few new friends and worsened its relations with several powerful nations.” Samantha Power, currently a member of President Obama’s administration, is one of the most influential advocates of military humanitarian interventions, yet an opponent of the precedence of national objectives. With reference to previous non-intervention cases, she notes that, “American leaders did not act because they did not want to” (Power, 2002). Simultaneously, identifying a coincidence between humanitarian intervention and American national interests.

In addition, the on-going discussion about rationality is gradually being subjected to an economic debate. Advocates of intervention such as Radu (2005) argue that the US is the only super power capable of providing ultimate forces for humanitarian interventions. The ongoing state budget crisis in the US has led the public to question the correlation between financial input and the upshot of humanitarian interventions, and whether or not armed interventions abroad are worth that much.[40] This debate, while cynical, is arguably an “expensive way to save lives” (Valentino, 2011). He bases his argument on the different budget calculations of past military interventions.[41] Valentino’s debate leads to an indispensable question concerning the most cost-effective methods and concept. Some scholars such as Mandelbaum (August 2011) have been even more pessimistic. He, for instance, states that future budget cuts will result in a situation where

“the feature of twenty-first-century foreign policy likeliest to be eliminated, and the one with which the country can most easily do without, is the type of the military intervention … in Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq” (Mandelbaum 2011).

The colonel had used violent means to contain the 2011 rebellions, which were interpreted by LAS leaders as human rights abuses on the civilian populace; thus, basic human rights had to be restored. The question of violence hereby comes up, not simply as an exercise in philosophical rhetoric, but as a practical problematic of politics and action (Arendt, 1969). The main trigger for UNSCR 1973 on Libya, “authorizing all necessary measures to protect civilians”[42] has been “the prospect of an imminent massacre,”[43] a “call for help,”[44] and the unending violation of basic human rights in Libya by the Qaddafi regime. Going by this justification for the colossal airstrikes, the world appears to be on the edge of a new age. The idealistic concept of military intervention to implement human rights in general and to protect the masses from their own leadership, in particular, not only gives the impression of being politically agreeable but, equally necessary. In the words of former British Prime Minister, Tony Blair:

“this is a new war for which we are fighting for values, a new internationalism where the brutal repression of whole ethnic groups will no longer be tolerated…for a world where those responsible for such crimes have nowhere to hide.”[45]

Western and Goldstein, in their extensive examination of the future of military interventions, note that there is a need for the international community to: (1) Act as rapidly as possible in the event of an outbreak overseas, thereby making an allowance for a standing force, which by their standards would be desirable; (2) equip interventions with suitable forces and resources; (3) be prepared for and stand against any antagonism and hostility that may arise in the case of civilian or coalition casualties; (4) organize multilateral alliances based on a coalition of international, regional, and national actors (JTF-Naples); finally, (5) have an exit scheme. (Western, J. and Goldstein, J 2011). Some, if not all of the five mentioned points, did apply to the Libyan case and the mission was labelled a success for the intervening powers.

While the aforementioned arguments are jarringly crucial in the development of this paper, of high importance is the legal status and the normative foundation of humanitarian interventions. Even though OUP was supported with a UNSC mandate, the legitimacy of the mission is still under scrutiny. Some of the aforementioned scholars have argued that the transatlantic community over-reached the former’s instructions which were well structured around a humanitarian reason, whereas NATO’s leading powers were calling for forcible regime change. The following section, is aimed at establishing the moral compass that guided the mission.

Operation Unified Protector

One month following the breakout of an insurgency in Benghazi, the LAS unanimously passed a resolution (a nearly unprecedented event in itself on February 22, 2011), persuading the international community to take action against Col. Qaddafi.[46] The UNSC followed with similar resolutions (1970 and 1973). Western-led interventions were initiated by France, and the United Kingdom, with command shared with the U.S. These various interventions by the allied powers were code-named: Operation Harmattan, Operation Ellamy, and Operation Odyssey Dawn respectively (there was also Operation Mobile, a Non-combatant Evacuation Operation led by Canada). NATO got involved not only in an attempt to unify the military command of the air campaign, but also to legitimize the mission by enforcing United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which resulted in the toppling of the regime. The rapidity with which the operations commenced (uprisings began February 17, 2011, and Operation Odyssey Dawn commenced March 19, 2011)[47] indicates that Qaddafi was certainly thought to have the power, and seemingly the will, to make good on his promise to destroy the protesters in Benghazi.[48] Other popular movements in Syria and the CAR have resulted in thousands of deaths, and yet neither, have gotten the kind of international attention the Libyan crisis received.[49]

The rationale, preparation and execution of humanitarian interventions has improved since the emergence of the idea of protecting civilians (R2P), but the moral underpinning of violating another nation’s sovereignty has largely remained unchanged. In order to ensure an effectual protection of civilians and their rights, the UN implemented the idea of “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P) in 2005, which was recommended by the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS)[50]. R2P connects a state’s privilege to sovereignty with its capacity to protect its population.[51] In its failure to do so, the responsibility is at that point shifted onto the diplomatic community to perform that duty (UN 2005:31).

Even though NATO insists its engagement in Libya was strictly for humanitarian purposes, its hasty response raised red flags on the subject of the desirability of the intervention. The following section discusses reasons why the decision making process that guided the establishment of a no-fly zone in Libya was hasty.

The Arab Spring uprisings reintroduced the concept of R2P yet again into the international scene, with uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt that did not motivate any large scale international interventions. However, peaceful demonstrations in Libya rapidly transformed into violent open war against Qaddafi and his loyalists, leading to a quick response from the international community. The first resolution (UNSCR 1970)[52] was adopted only ten days following the start of the demonstrations in Eastern Libya. This resolution was closely followed by UNSCR 1973 calling for civilian protection by any means possible (as such a no-fly zone was imposed, and airstrikes were launched on the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya by western nations). The quick response the Libyan crisis received from the Security Council has come under scrutiny as equally or even more appalling human rights abuses in Rwanda, Syria and Yemen were overlooked for an unpredictably long time. It took the Council almost a year after the start of the Yemen uprising to pass a resolution (Resolution 2014 – October 21, 2011), which did not sanction any R2P action, but advocated a Yemeni-led political appeasement process.[53] Though the west can ascertain that it does not retain the capability to intervene militarily in every occurrence of human rights abuses, and therefore reserves the right to restore human rights whenever the opportunity presents itself, Booth responds that this “merely says that on a particular occasion one (NATO) acted in accordance with humanitarian objectives; not that as a matter of principle one (NATO) acts out of respect for them” (Booth 2001). The question that follows is: Why was Qaddafi’s regime targeted so quickly by the international community? There are a number of reasons that possibly guided the quick response, all of which revolve around national interests of individual states (or foreign policy interests), realpolitik calculations, and geo-strategic considerations.

Firstly, Qaddafi’s erratic nature had not made him many friends on the diplomatic scene, and could be one possible reason that guided the quick military response that resulted in his overthrow from power. Qaddafi’s rise to power was accompanied by an extremely hard power foreign policy technique, which had been inspired by the late President Nasser. Qaddafi’s ideology was outlined most notably in 1977 as the “third universal theory”. This ideology shaped the external policies of the Libyan state from the early 1970s to 1990s, and it was promoted as applicable to all regimes. Underlying this ideology was Qaddafi’s imperative to stay in power and the need to deter and defeat both internal and external challenges that could threaten his regime’s security. Qaddafi had finally come to the realization that a small nuclear Libyan arsenal force would successfully serve as a deterrent to any country while solidifying Libya’s status on the world stage. Following the Nuclear Non-Proliferation treaty (NPT) extension Conference in June 1995, Qaddafi said, “Peace will also be in danger as long as there is no balance and nuclear deterrence in the region, in that the Israelis possess more than 200 nuclear heads while the Arabs do not have a single one. The Arabs should possess this weapon to defend themselves. It would be legitimate and for the sake of peace.”[54]

One alleged reason Libya occupied the Aouzou Strip in Chad in 1975 was that the area was thought to be rich in uranium deposits–U.S. intelligence later confirmed that Libya had acquired ‘yellow cake’ from the region in 1978. Libya’s main partner in the nuclear field, however, was the Soviet Union, and France who agreed to build a nuclear research plant in Libya in 1975. During the decade following the discovery of oil depots, Qaddafi’s terrorist activities took shape, drawing a response from the Reagan administration. A campaign against Soviet-sponsored terrorism was launched within weeks of Reagan’s inauguration ceremony, and Libya was spotlighted, as the base for soviet subversion. Qaddafi was looked upon as one of the most dangerous men in the world as such diplomatic and economic links with the U.S became strained. On April 15th, 1986, Reagan ordered an air attack on Tripoli and Benghazi in response to an earlier Libyan-sponsored assault on La Belle Discotheque, a West Berlin hangout of American G1s that killed one American and left almost sixty others injured. U.S. counterattacks successfully left members of Qaddafi’s family severely hurt alongside a dead daughter, and Qaddafi supposedly calmed down his hard power diplomacy for a while. It seems in actual fact; he only really became discreet and more determined. From disclosures arising after the seizure of the BBC China in 2003, it became obvious that Qaddafi’s second nuclear weapons effort of 1989, with roots in Pakistan, was born after these American attacks. During a televised address in April 1990, Qaddafi had this to say with regards to the American attacks of 1986: “If we had possessed a deterrent – missiles that could reach New York – we could have hit it at the same moment. Consequently, we should build this force so that they and others will no longer think about an attack….Regarding reciprocal treatment, the world has a nuclear bomb, we should have a nuclear bomb.”[55]

Libya’s transformation from nuclear state in 2003 mostly opened up a pathway for Qaddafi mimicry (there was hardly ever an article in western media that did not reference his ridiculous and lavish appearance (Pargeter 2012). Summarily, his strict anti-western foreign policy naturally put him at odds with western leaders and even some of the LAS leaders eventually fell short of his expectations[56] making Libya an easy target in 2011.[57] Besides, Robert Hugh (2011) states that there were “three abortive plots, farmed out to David Stirling and sundry other mercenaries under the initially benevolent eye of Western intelligence, to overthrow Qaddafi’s regime between 1971 and 1973 in an episode known as the Hilton Assignment.”[58] In the same light, Emadi (2012) points to Qaddafi’s uncooperative foreign policy towards the west, and the U.S.’s determination to penalize him for his role in the explosion of the Pan Am flight at Lockerbie in 1988,[59] as a likely motivation for OUP. The 2011 uprising thereby provided the perfect platform not only for intervention, but also for regime change.

In addition, the Aozou strip incident[60] was still fresh in the minds of AU leaders, who feared a spillage of the crisis into neighboring countries. For this reason, they contributed their support to an intervention without taking into consideration the actual terms or interpretation.[61] In spite of Qaddafi’s efforts at reintegrating Libya into the international community and his unquestionable attempts at refining Libya’s international affairs across the globe since 2003, Libya still somehow managed to remain a politically isolated nation without many reliable allies. Qaddafi’s infamous interference in the internal matters of other countries, including his visit to Malawi in 2002, when President Muluzi vacated the official presidential villa for President Qaddafi and his entourage;[62] his claim to leadership of the Arab world following Nasser’s passing; his refusal to attend the Arab summit conference at Algiers in November 1973; his support for international terrorism; his sometimes idiosyncratic political perceptions such as his condemnation of the Israeli-Egyptian negotiations at Geneva in December; his launching of a prolonged anti-Sadat campaign; and his radical interpretation of Islam all contributed to isolating Libya for four decades, leaving him little to depend on in the face of an offensive attack.[63] It therefore came as little surprise that the LAS leaders augmented UNSCR 1970 and 1973 culminating in the first NATO-led operation in Libya, supported by the LAS, the Organization of Islamic Conference, the Gulf Corporation Council, and assisted by four Arab countries (Gaub 2013 and, Hehir 2013).

Secondly, disloyal cronies sought political opportunities, using the insurrection to create the National Transitional Council – NTC in Benghazi on March 5, 2011. The NTC met in Benghazi shortly after the beginning of demonstrations in the East, and declared itself the sole representative of the Libyan people; later gaining recognition by France, Britain, Qatar and Nigeria (Vandewalle 2012). Mustafa Abdeljalil, Mamoud Jibril, and Ali Issawi and other NTC members used their new found authority to press the LAS and the west for military and humanitarian assistance with the ongoing crisis. The international community could therefore provide the rebel groups (under the auspices of the NTC) with weapons, but not the Libyan government, which by then was considered illegitimate by the US, France and Great Britain. This, therefore, meant that the illegitimate regime had to be removed with immediate effect, and anything short of that would have been considered a failure. International recognition, meant the establishment of diplomatic ties with the new government who promised to re-institutionalize the state, thus, proving that the international community preferred to negotiate diplomacy and even politics with the NTC leaders, than with the colonel, who had been branded an autocrat.[64] Western interests and realpolitik calculations once more trumped norms when, as early as March 10, some western states were already actively defending the rebel leaders in a bid to replace Qaddafi’s regime. This decision was no doubt guided by practical considerations (regime change) more so than the need to enforce normative standards (humanitarian motives).

Furthermore, one of the reasons for which the U.S. operation in Libya (Odyssey Dawn–OD) was initiated was in order that the U.S. military could directly access Qaddafi’s nuclear stock pile. Qaddafi was reported of being in possession of a weapon’s stock pile in the South; the material was left under Col. Qaddafi’s control by a US-backed disarmament pact.[65] This was the U.S.’s ultimate concern for rushing into the intervention for fear that the weapons might fall into the possession of terrorist and extremist groups in the region, such as Anwar al-sharia, Al Qaeda, and Al Shabbab.[66] According to a report by the Congressional Research Service (CRS), “terrorist groups are exploiting this opportunity, and the situation grows more dangerous with each passing day, a situation that directly impacts U.S. national security.”[67] Gen. Carter Ham, commander of AFRICOM went as far as confirming that “as many as 20,000 surface-to-air missiles were in the country when the operation began [and that] many of those, we know, are now not accounted for.”[68] The U.S. succeeded in this mission because the IAEA’s visit to the Tajoura Nuclear Facility in Tripoli and a uranium concentrate storage facility in Sabha in December 2011 resulted in the conclusion by the nuclear watchdog organization that the two undeclared chemical weapons stockpile had neither been moved nor reported missing during the uprising and NATO’s mission.[69]

In addition, OD was run in affiliation with AFRICOM (Joint Task Force Odyssey Dawn).[70] AFRICOM, also known as US-African Command, was created in 2008, as a kind of geographic combatant command, one focused mainly on stability and engagement operations rather than war-fighting (Joe Quartararo, Sr et al 2011). However, the Libyan revolution provided an opportunity for this command to take on more responsibilities.[71] The presence of this well-resourced command in Africa was convenient enough to motivate a rapid response. This meant that the U.S. and NATO already had access to some of the resources they needed and could take on the operation at little cost.

Finally, NATO needed to secure a win following an open-ended war that had been ongoing in Afghanistan. OUP appeared to be a war of necessity rather than choice, aimed at reassuring other NATO member states of its supremacy. The U.S., which was already in wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, was a bit reluctant to initiate a lone intervention in Libya. Germany also displayed lack of interest in participating militarily in the intervention in Libya along with NATO. Engaging militarily in Libya, and winning, could potentially serve to reassure transatlantic partners of NATO’s supremacy in international politics. From a political viewpoint, U.S. solo intervention could potentially be perceived as yet another attack on Islam. Meanwhile, the African continent could potentially view such an attack as imperialistic. This problem was curbed by the formation of a coalition that included Arab countries and African states rendering JFC-Naples a “necessary operation” (Quartararo et al 2012). Together this alliance was able to successfully execute a combatant mission, and defeat Qaddafi’s militia from the air, thereby enabling his ouster from power within seven months, without suffering military casualties, just like some western leaders had hoped for (Vandewalle 2012).

Conclusion and implications for future humanitarian interventions

The purpose of this paper was to inquire into whether OUP was rushed, find out possible reasons for why it might have been rushed, and evaluate the moral foundation of the whole mission. I began by demonstrating that the Libyan case was different from past and ongoing cases of civil unrest that ignited international interventions. I did this by comparing the Libyan case with the Syrian and Bahraini cases to depict the amount of human rights violations that were recorded in each case, and how the international community responded (with partiality) to these various crises. The conclusion drawn from the case comparison was that the decision-making process sanctioning military force in Libya was quite rushed, and the strategic purpose of the mission and the ultimate goal were both unclear and appeared to be in conflict.

The follow-up section of the paper builds on possible reasons for why the intervention into Libya may have been rushed. While humanitarian aims have been cited as the ultimate purpose of the intervention, I argue that the decision-making process that guided resolution 1973 was based on national interests, realpolitik calculations, geo-strategic considerations and domestic politics. These reasons while plausible, do not quite justify the morality of the mission, as such I analyzed the moral permissibility of OUP. The reasons that possibly guided OUP were firm enough to necessitate military force, but not well-timed to support the humanitarian foundation of the intervention. In other words, the time frame within which the intervention was authorized was short, and enough effort had not gone into trying to curb the revolution through peaceful means. International sanctions targeted solely at the regime or an effective road map to peace probably would have differed in major ways from regime change and outright disregard for territorial integrity in an internal insurgency that was yet to escalate into a genocidal war. In spite of the fact that Qaddafi’s personality and foreign policy played a huge role in motivating a hasty response, the absence of a veto to the UNSC’s resolutions enhanced the willingness to intervene on such short notice. I came to this conclusion after critically analyzing the humanitarian justification advocated in defense of the intervention, along jus ad bellum principles – OUP was not morally permissible.

NATO’s intervention into Libya has been applauded by a host of scholars, western media, and even Libyans themselves[72] for addressing the plight of the Libyan people under an autocrat. Even though, the absence of a humanitarian emergency was glaring in Libya, the west continued pushing for regime change under a humanitarian pretext. By the end of the mission in October, it had become obvious that the quest for regime change was the focal point of the intervention, not the need to protect civilians. OUP, as has been demonstrated, did little to serve the principles of humanity and the ethics of humanitarian interventions, thus, illustrating that the norm-based argument of humanitarian interventions is morally justifiable to necessitate a military intervention abroad, but not the driving force. Regardless, liberal humanitarianism will continue to appeal to our collective human conscience to alleviate the sufferings of fellow humans abroad (Nuruzzaman, 2013).

The intervention was a socio-political catastrophe as it left behind a politically damaged country with no certain future. From the analysis presented in section four of this paper, the ‘intention’ of the intervention was unclear as has been demonstrated (by the large number of casualties it left). It is easy for one to wonder whether or not OUP served the principles of humanity and the ethics of humanitarian interventions. Summarily, the actions of the transatlantic partners in Libya in 2011 were hasty, and would have been permissible only in the case of an actual (not verbal) genocide. As such, it is necessary for the following steps to be taken into consideration before any armed intervention is enforced:

- There must be substantial evidence of genocide;

- The military intervention must be a last resort after all other diplomatic efforts at putting a stop to the genocide have failed;

- Legitimization and legalization of the intervention should come from the UN General Assembly, not the UNSC;

- Finally, the intervening country (s) should aim at bringing an end to the genocide, and must desist from engaging in nation-building.

The precedent has been set in Libya, and R2P has become a topic of contention among scholars.[73] The importance of realpolitik calculations, and national interests politics was proven by the lack of military engagement in Bahrain, Yemen, and to an extent Syria among other countries. Whether or not R2P will be subject to debates as the United Nations tussles with any future instances of civilian abuse by a regime deemed repressive, is left to be seen. The most acceptable explanation for military humanitarian intervention against an autonomous region is the normative justification grounded in humanitarian intentions (the need to protect unarmed civilians from abuse, and restore human rights). Any other reason (whether it be geo-strategic considerations, or national interests) is intolerable in international politics and contemporary scholarship. Accordingly, the U.S., Britain and France all advanced normative arguments that pointed to human rights abuse, fully aware of the fact that this motive was well suited to the Libyan situation, where a diplomatically secluded and an unconventional autocrat ruled for 42 years.

R2P was discredited by western abuses in Libya, creating what Prashad (2012) calls “a Libyan winter,” the immobility of the west toward President Assad, and the UNSC’s inexplicable indifference toward the instability in Bahrain and Yemen. Furthermore, the concealed agenda of regime change in OUP’s mission, tainted the doctrine of civilian protection. One dictator was replaced with a group that simply rebranded themselves as democratic, and promised to reform the bureaucracy – this reformation remains to be seen. Conclusively, the assumption that the importance of norms overtrumps international and state interests is at the moment still a misapprehension. Nevertheless, the questions that remain are whether or not future R2P interventions will be authorized and under what exceptional conditions will some of the more discreet UNSC member nations warrant an intervention.

References

Alex de Waal. 2013. “African Roles in the Libyan Conflict.” International Affairs 2: 365-379. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Anderson, Lisa. 2011. “Demystifying the Arab Spring: Parsing the Differences between Tunisia, Egypt and Libya.” Foreign Affairs. HeinOnline.

Arendt, Hannah. 1966. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harvest.

Barnett, Michael. 1997 “The UN Security Council, Indifference, and Genocide in Rwanda.” Cultural Anthropology. Pp. 551-578, Vol. 2. Wiley: American Anthropological Association.

Barnett, Kenneth. 2013. Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bello, Walden. August 2011. “The Crisis of Humanitarian Intervention.” Foreign Policy in Focus.

Bob, Clifford. 2005. The Marketing of Rebellion: Insurgents, Media, and International Activism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bowen, Wyn. 2006. Libya and Nuclear Proliferation Stepping Back from the Brink. Routledge: New York.

Blanchard, Christoph M. September 29, 2011. “Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy,” CRS Report RL 33142. Washington, DC: Office of Congressional Information and Publishing. U.S. Library of Congress, (p. 12).

Bush et al. 2011. “Humanitarian imperialism.” Review of African Political Economy 38 (129): 357‒365.

Chapin, Helen. ed. 2004. Libya: A Country Study. Montana: Kessinger Publishing.

Chomsky, Noam. 2002. The New Military Humanism: Lessons from Kosovo. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press.

Chorin, Ethan. 2012. Exit the Colonel: the Hidden History of the Libyan Revolution. United States: PublicAffairs.

Curtis, Adam. March 28, 2011.”Liberal Imperialism. Goodies and Baddies: A History of Humanitarian Intervention.” BBC blog.

Dawson, Ashley. 2011. “New World Disorder: Black Hawk Down and the Eclipse of U.S. Military Humanitarianism in Africa.” African Studies Review, vol. 54, no. 2.

Emadi, Hafizullah. 2012. “Libya: The Road to Regime Change.” Global Dialogue, vol. 14.

Etziona, Amitai. 2012. “The Lessons for Libya.” Military Review January-February edition.

Fassin, Didier. 2012. Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the present. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Finnemore, Martha. 1996. “Constructing Norms of Humanitarian Intervention.” in The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics, edited by P.J. Katzenstein. New York, Columbia University Press.

Forte, Maximillian. 2012. Slouching towards Sirte: NATO’S War on Libya and Africa. Montreal: Baraka Books.

Gaub. Florence. 2012. “Libya: Has Gaddafi’s Dream come true.” Politique Etrangère, vol. 77, n° 3. Paris: Institut Francais des Relations Internationale.

Gaub, Florence. 2013. “The North Atlantic Treaty Organization and Libya: Reviewing Operation Unified Protector.” Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press.

Gibbs, David. 2009. First Do No Harm: Humanitarian Intervention and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. Nashville TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Heilbrunn, Jacob. 2011. “Samantha and her Subjects,” The National Interest

Hehir, Aidan. 2013. “The Permanence of Inconsistency: Libya, the Security Council and the Responsibility to Protect.” International Security, vol. 38, no. 1. MIT Press.

Holzgrefe, L. 2003. “The Humanitarian Intervention Debate.” Pp. 15-52 in Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemmas, edited by J. L. Holzgrefe, and Keohane O. Robert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lango, John W. 2009. “Evaluating the Iraq War by Just War Principles,” Teaching Ethics. Vol. 5, no. 1.

Lacher, Wolfram. 2013. Fault lines of the Revolution: Political Actors, Camps and Conflicts in the New Libya. Germany: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

Loschky, J. 2012. “Opinion Briefing: Libyans Eye New Relations with the West U.S. Approval Among Highest ever Recorded by Gallup in MENA Region.” Available at http://www.gallup.com/poll/156539/opinion-briefing-libyans-eye-new-relations-west.aspx.

Mainwaring, Cetta. 2012. “In the Face of Revolution: The Libyan Civil War and Migration Politics in Southern Europe.” Pp. 431-451 in The EU and Political Change in Neighboring Regions: Lessons for EU’s Interaction with the Southern Mediterranean, edited by Stephen Calleya et al. Malta: University of Malta Press.

May L., Rovie E., and Viner S. 2006. The Morality of War: Classical and Contemporary Readings. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

McMahan, Jeff. 2004. “The Ethics of Killing in War.” Ethics, vol. 114, no. 4.

McMahan, Jeff. 2005. “Just cause for War.” Ethics & International Affairs, vol. 19, no. 3.

McMahan, Jeff. 2006. “On the Moral Equality of Combatants.” Pp. 377-393 in Journal of Political Philosophy, vol. 14, no. 4.

McMahan, Jeff. 2012. “Rethinking the Just War” Part 1 and 2 can be found at: http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/11/rethinking-the-just-war-part-1/?_r=0 http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/12/rethinking-the-just-war-part-2/?_r=0

Nuruzzaman, Mohammed. 2013. “The ‘Responsibility to Protect’ Doctrine: Revived in Libya, Buried in Syria.” Insight Turkey http://www.readperiodicals.com/201304/2969263781.html

Orford, Anne. 2003. Reading Humanitarian Intervention: Human Rights and the Use of Force

In International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pack, Jason. 2013. “The Center and the Periphery.” Pp. 1-22 in The 2011 Libyan Uprisings and the Struggle for the Post-Qadhafi Future, edited by Jason Pack. New York: St. Martin’s Press LLC.

Pargeter, Alison. 2012. Libya: The Rise and Fall of Qaddafi. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Pattison, James. 2011. “The ethics of Humanitarian Intervention in Libya, Ethics & International Affairs.” Ethics and International Affairs, vol. 25, no. 3.

Putnam, Robert D. 1988. “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games.” International Organization, vol. 42, no. 3.

Prashad, Vijay. 2012. Arab Spring Libyan Winter. Edinburgh: AK Press.

Radu, Michael. 2005. “Putting National Interest Last: The Utopianism of Intervention.” Global Dialogue, vol. 7, no. 1-2.

Reed, Thomas C. and Danny Stillman. 2009. The Nuclear Express. Pp. 268-277. Minneapolis: Zenith Press.

Roberts, Hugh. 2011. “Who said Gaddafi had to go?” London Review of Books, vol. 33, no. 22.

Ronald, Bruce St John. 2006. Libya and the United States: The Next Steps (http://www.acus.org)

Ronen, Yehudit. 2002. “Qadhafi and Militant Islamism: Unprecedented Conflict.” Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 38, no.4.

Rousseau, Richard. “Why Germany abstained on UN Resolution 1973 on Libya.” Foreign Policy Journal, http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2011/06/22/why-germany-abstained-on-un-resolution-1973-on-libya/

Roth, Kenneth. 2013. “Syria: What Chance to Stop the Slaughter?” The New York RE Blog. Http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2013/nov/21/syria-what-chance-stop-slaughter/

Snyder, Jack. 1991. Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition, Ithaca and London, Cornell University Press.

Skocpol, Theda. 1979. States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia and China. London: Cambridge University Press.

Stefan Hasler. 2012. Explaining Humanitarian Intervention in Libya and Non-Intervention in Syria. Phd Dissertation, Naval Post Graduate School. Monterey, California.

Vandewalle, Dirk. March 7, 2011. “After Ghadafi.” Newsweek.

Vandewalle Dirk. 2012. A History of Modern Libya. London: Cambridge University Press.

Watenpaugh, Keith. 2010. “The League of Nations’ Rescue of Armenian Genocide Survivors and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism, 1920-1927.” American Historical Review. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weiss, Thomas. 2012. Humanitarian Intervention. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Wilson, Richard A. and Richard D. Brown. 2009. “Boundaries of Humanitarianism.” Pp. 1-30 in Humanitarianism and Suffering: The Mobilization of Empathy, edited by R.A. Wilson and D.B. Richard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wright, John. 1982. “Libya a Modern History. London: Croom Helm.

Internet Sources

Anger Mismanagement: Bahrain’s Crisis Escalates. http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/anger-mismanagement-bahrain%E2%80%99s-crisis-escalates

Al Jazeera (2011a). Fresh violence Rages in Libya. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2011/02/201122261251456133.html

Al Jazeera (2011b). No let-up in Gaddafi’s Offensive. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2011/03/2011317645549498.html

Resolution 1970 (2011): Adopted by the Security Council at its 6491st meeting, on 26 February 2011 http://www.icc-cpi.int/NR/rdonlyres/081A9013-B03D-4859-9D61-5D0B0F2F5EFA/0/1970Eng.pdf

Resolution 1973 (2011): Adopted by the Security Council at its 6498th meeting, on 17 March 2011 http://www.nato.int/nato_static/assets/pdf/pdf_2011_03/20110927_110311-UNSCR-1973.pdf

Reuters. “Factbox: Libya’s military: what does Gaddafi have?” Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/08/us-libya-military-idUSTRE7274QI20110308

Reuters. “U.N. chief speaks of “grisly reports” from Syria.” Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/03/03/us-syria-idUSL5E8DB0BH20120303

Reuters. “Analysis: France sees Libya as way to diplomatic redemption.” Reuters. www.reuters.com

Reuters. “Most French favor U.N. military action in Syria” Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/02/10/us-france-syria-poll-idUSTRE8190N820120210

Reuters. “Sarkozy, Cameron: Gaddafi must step down now.” Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/10/france-britain-libya-idUSPISAEE74J20110310

Chigozie Ibeh. 2013. “Libya: The Moral Permissibility of Operation Unified Protector.” http://www.e-ir.info/2014/01/25/libya-the-moral-permissibility-of-operation-unified-protector/

Yemen: Timeline of protests against Ali Abdullah Saleh http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/yemen/8774702/Yemen-timeline-of-protests-against-Ali-Abdullah-Saleh.html

Security Council Resolutions http://www.un.org/en/sc/documents/resolutions/

NATO operations in Libya: data journalism breaks down which country does what

http://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/may/22/nato-libya-data-journalism-operations-country

Libya Operation Details https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AonYZs4MzlZbdFY5dFNsZDdfamdPQUdfbW5HcVR6eUE&hl=en_US#gid=0

Endnotes

[1] President Obama speaking at Cairo University on June 4, 2009. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-cairo-university-6-04-09

[2] The major players in Libya included former Qaddafi cronies and civilians (mostly from the Eastern part of the country) on one side, who were fed-up with the socio-economic stagnation, and Qaddafi and his loyalists.

[3] French philosopher and public intellectual Bernard Henri Levi, for instance, was among those who advocated an intervention into Libya. Even the League of Arab States (LAS) leaders joined the cause (and suggested that the killings had to be stopped; human rights had to be restored etc.) (Curtis 2011).

[4] “Even the most seasoned of Libya-watchers were stunned that Libyans were finally able to shake off the fear and to rise up en masse…Had NATO not entered the conflict when it did, it is likely that the rebel forces would not have been able to dislodge Qaddafi from the west.” Pargeter 2012, p. 8).

[5] Operation Unified Protector (OUP) is one of the three NATO interventions that were termed humanitarian, was aimed at protecting “civilian-populated areas under attack or threat of attack. The mission comprised of three elements: an arms embargo, a no-fly-zone and actions to protect civilians from attack or the threat of attack.” http://ww0w.jfcnaples.nato.int/Unified_Protector.aspx

[6] Qaddafi’s forces according to reports, were guilty of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity (accused of using civilians as human shields), as they went about trying to squash the uprising. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/apr/06/gaddafi-using-civilian-human-shields With regards to military action UNSCR 1973 specifically called for: (1) an immediate ceasefire and a complete end to violence and all attacks against, and abuses of, civilians (para. 1). (2) Authorized Member States, acting nationally or through regional organizations or arrangements, to take all necessary measures to protect civilians and civilian populated areas under threat of attack, including civilians in Benghazi (para. 4). (3) The resolution specifically excluded the establishment of a foreign occupation force of any form in any part of Libyan territory (para. 4). (4) Called for Members States of the LAS to cooperate in the implementation of the measures outlined in paragraph 4 (paragraph 5). (5) Authorized the establishment of a no-fly zone in Libyan airspace (para. 6). That flight ban would not, however, apply to flights that have as their sole purpose, humanitarian aid, the evacuation of foreign nationals, flights authorized for enforcing the ban or “other purposes deemed necessary for the benefit of the Libyan people” (para. 7). (6) Paragraph 8 authorized Member States to take all necessary measures to enforce compliance with the ban on flights imposed under paragraph 6. (7) Called on all Member States to provide assistance, including any necessary over flight approvals, for the purpose of implementing paragraphs 4, 6, 7 and 8. United Nations Security Council S/RES/1973 (2011).

[7] Department of Defense (DOD) press briefing by Vice Admiral Bill Gortney, Director of the Joint Staff, March 19, 2011. www.defense.gov/transcripts/transcript.aspx?transcriptid=4786

[8] Details of Operation Odyssey Dawn have been discussed in this article: “The Weapons We’re Hitting Gadhafi With,” March 20, 2011 www.defensetech.org.

[9] Images of the command structure can be found at http://www.defense.gov/DODCMSShare/briefingslide/358/110328-D-6570C-001.pdf

[10] DOD press briefing by Rear Admiral Gerard Hueber, March 23, 2011. www.defense.gov/transcripts/transcript.aspx?transcriptid=4794

[11] DOD press briefing by Vice Admiral Bill Gortney, Director of the Joint Staff, March 28, 2011.

[12] Vandewalle (2012) notes February 17, 2011 as the first day the protests began following the arrest of Farthi Tabil, and March 17, 2011 as the day UNSCR 1973 authorized a no-fly zone over Libya, a mandate that went took effect on March 19, 2011; with the commencement of US-led coalition air strikes in the region.

[13] This is a fact sheet that discusses the timeline of the Syrian crisis http://www.unhcr.org/5245a72e6.pdf

[14] Landis, Joshua. 2012. “The Syrian Uprising of 2011: Why the Assad Regime is Likely to Survive to 2012.” Middle East Policy, Vol. XIX, No. 1. Cortini Kerr and Toby Jones. 2013. “A Revolution Paused in Bahrain” in The Arab Springs: Dispatches on Militant Democracy in the Middle East. Pp. 208-214. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

[15] “The current law of the UN Charter does not accommodate the bombing of Yugoslavia, since the action was neither based on a Security Council decision under Chapter VII(2) of the UN Charter, nor pursued in collective self-defence under Article 51 of the Charter – the only two justifications for use of force that are currently available under international law.” Ove Bring (December 2000).

[16] “Many villages are now blanketed with the choking white clouds several nights a week, and officers routinely shoot the American-made blue canisters into private homes… Protesters also say the government has started using a new chemical, CR gas, which is significantly more potent than the CS gas that is typically deployed to disperse crowds.” Carlstron, Gregg. 2013. “In the Kingdom of Tear Gas.” Pp. 239-246 in The Arab Revolts: Dispatches on Military Democracy in the Middle East. Edited by David McMurray and Amanda Ufheil-Somers. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (P. 242).

[17] “The violence has continuously simmered since then, punctuated by periodic surges. As of February 2013, more than 100 people had died in police crackdowns on anti-regime demonstrations and retaliatory attacks by insurgents. The government also has imprisoned hundreds of other political opponents. Those numbers might not seem all that large, but Bahrain’s population is barely 1.2 million.” Ted Galen Carpenter (July 2013), http://www.cato.org/blog/bahrain-emerging-washingtons-next-middle-east-crisis.

[18] Qaddafi loyalists regrouped in towns like Bani Walid and Tarhouna even after he had fled the capital of Tripoli. Reported by Steven Sotloff outside of Bani Walid on Tuesday, Sept. 06, 2011 http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2092028,00.html

[19] Between 1980 and 2000, radical Islamic groups, especially in Eastern Libya, challenged the regime. Qaddafi’s answer was usually a “systematic iron- fist- policy” with repression and violence that was often followed by efforts to calm down the situation with religious and economic reforms. This policy almost always brought the uprisings to an end, and a decade of relative domestic quiet ensued between 2000 and 2010. Ronen, Yehudit. 2002. “Qaddafi and Militant Islamism: Unprecedented Conflict.” Pp. 1-16 in Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 38, no.4; Pargeter, Alison. 2005. “Political Islam in Libya.” Terrorism Monitor, vol. 3, Issue: 6; and “Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East (V): Making Sense of Libya.” Crisis Group Middle East/North Africa Report N°107, 6 June 2011.

[20] “It is important to restructure in a way that does not repeat the mistake of concentrating wealth in the hands of a few,” Qaddafi said. “The first target in this privatization will be the citizens of Libya and increasing their private ownership.” This statement followed an announcement of economic reforms at the World Economic Forum 2005 in Davos. Thomas Crampton, “Qaddafi son sets out economic reforms: Libya plans to shed old and begin a new era”, New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/28/news/28iht-libya_ed3_.html_

[21] Jamahiriya translates to Republic.

[22] “Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East (V): Making Sense of Libya.” Crisis Group Middle East/North Africa Report N°107, June 2011.

[23] As I will further explain in “section 4” of this paper, OUP was a typical humanitarian mission for NATO. It started off with the French and British heading separate missions. The US later formed a unified front called JFC-Naples, and NATO came in after UNSCR 1973 was issued as a unifying force to lead the mission.

[24] Such as, Hugo Grotius. 1625. De Jure Belli ac Pacis and Emer de vattel. 1758. Le Droit des Gens.

[25] Davide Rodogno however maintains that the motive behind Great Britain’s action was anything but humanitarian. He states that “it was the best option to keep Napoleon happy, to check the French imperial ambitions in the eastern Mediterranean, and to find an appropriate exit strategy through the work of a European commission” (Rodogno 2012).

[26] The cases mentioned were all cited as cases of humanitarian interventions but their implementation and drive were definitively different from recent interventions. The guiding principles of who was human and in need of saving served as an incentive for the intervening states. For instance, the French intervention in Lebanon/ Syria 1860-1861 was exclusively drive to assist the Christian population. Similarly, other considerable human rights abuses by the same nations remained overlooked. The wars fought against the Othman empire by the medieval Concert of Europe to save Christian minorities within the dynasty have also been cited by Murphy as a humanitarian intervention. Holbraad (1970, p. 162-76).

[27] The works of Vandewalle (1998), Wright (1982) and El Fathaly and Chackerian (1977) all contain detailed histories of the state of affairs in Libya since independence.

[28] Qaddafi’s domestic policy can be found in the Green Book, whose first volume was published on September 17, 1976.

[29] Because I am arguing that OUP was rushed, it will only make sense that I throw in some case comparisons that further elucidate this claim.

[30] The newspapers I selected were very active in reporting daily updates on both the Libyan and Syrian crisis often from reliable eyewitness accounts.

[31] Sources could include: www.gallup.com or www.pollingreport.com, www.France24.com and www.infratest-dimap.de. Most data is estimated, due to the absence of an official database.

[32] The following countries that are referred to in this paper as the transatlantic community, include: the United States, Canada, Turkey, Greece, the UAE, Italy, Jordan, Sweden, France, Denmark, Romania, Qatar, Spain, Norway, Bulgaria and Belgium.

[33] Wilson, Richard A. and Brown Richard. 2009. “Introduction.” Pp. 1-28 in Humanitarianism and Suffering: The Mobilization of Empathy, edited by Wilson R.A. and Brown R. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

[34] President Obama said this in a public speech following the culmination of the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 http://m.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2011/05/19/remarks-president-middle-east-and-north-africa%20, (May 19, 2011).

[35] Tim Allen and David Styan. 2006. “A Right to Interfere? Bernard Kouchner and the New Humanitarianism,” Journal of International Development. Vol. 12, no. 6

[36] In Germany, the government initially was strongly criticized for its abstention in the UN Security Council regarding UN resolution 1973. “Germany’s abstention led to a public relations meltdown abroad and at home”, media concludes afterwards. Constanze Stelzenmueller, “Germany’s unhappy abstention from leadership.” Financial Times, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/2490ab8c-5982-11e0-baa8-00144feab49a.html#axzz1e5fV3QbH

[37] Anup Shah makes mention of a variety of open source publications in the U.S. that depicted individual opinions of OUP and the resolution advocating it (Shah 2011). http://www.globalissues.org/article/793/libya. A more quantitative data analysis of public opinion can be found at Gallup surveys. The results from the survey indicate that Libyans were more likely than their Arab counterparts to support the 2011 intervention. 75% Libyans answered yes in favor of the intervention, whereas 33% in Tunisia, 14% in Algeria, and 13% in Egypt answered “yes” to the same question at a 95% confidence interval. The survey was carried out in March and April 2012 (accessed September 2014). http://www.gallup.com/poll/156539/opinion-briefing-libyans-eye-new-relations-west.aspx

[38] Ken Roth is the executive director of Human Rights Watch, and he is a moderate who believes that humanitarian interventions are sometimes uncalled for, as such should be preserved for more important events such as ethnic cleansing or any sought of large scale murders (“War in Iraq: Not a Humanitarian Intervention” Human Rights Watch World Report 2004: Human Rights and Armed Conflict. p. 18).

[39] Nevertheless, there was fear from Chad and Niger of a possible spillover, especially since the events that occurred in 1972 were still present in their minds. (Alex de Waal. 2013. “African Roles in the Libyan Conflict of 2011.” International Affairs 89: 2 (2013) 365–379. The Royal Institute of International Affairs: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

[40] During the June 2011 conference of U.S. Majors in Baltimore, government spending on projects outside the U.S. was heavily criticized. Cooper, Michael. 2011. “Mayors see end to wars as fix for struggling cities.” New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/18/us/18cities.html?pagewanted=all

[41] “Each of the more than 220 Tomahawk missiles fired by the U.S. military into Libya, for example, cost around $1.4 million. In Somalia, a country of about 8.5 million people, the final bill for the U.S. intervention totaled more than $7 billion. Scholars have estimated that the military mission there probably saved between 10,000 and 25,000 lives. To put it in the crudest possible terms, this meant that Washington spent between $280,000 and $700,000 for each Somali it spared. As for Bosnia, if one assumes that without military action a quarter of the two million Muslims living there would have been killed (a highly unrealistic figure), the intervention cost $120,000 per life saved. Judging the 2003 Iraq war–now a multitrillion-dollar adventure–primarily on humanitarian grounds, the costs would be orders of magnitude higher.” Valentino (November/December 2011). http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/136542/benjamin-a-valentino/the-true-costs-of-humanitarian-intervention

[42] UN Security Council, SC 10200, 17 March 2011, http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2011/sc10200.doc.htm.

[43] This was a phrase used by President Obama during a speech regarding his stance on the Libyan crisis and the R2P. New York Times. “Obama’s Mideast Speech.” http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/20/world/middleeast/20prexy-text.html?pagewanted=all

[44] The UNSC adopted UN Resolution 1973 (2011), allowing all necessary measures to protect Libyan civilians, by a vote of 10 in favor and 5 absentees.

[45] “A New Generation draws the Line.” Cited by Chomsky (1999, p. 3).

[46] “Early condemnation and calls for action in response to the crisis by the League of Arab States on 22 February 2011, the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) on 22 February 2011, and the African Union (AU) on 23 February 2011 were crucial for the international community to move forward with stronger measures to protect civilians.” http://responsibilitytoprotect.org/index.php/crises/crisis-in-libya

[47] Attached at the end of this paper is a timeline of the Libyan uprising.

[48] Qaddafi’s speeches were featured in Menas Associates. June 2011. Libya Focus; and an audio segment of the speech could be fund at http://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2011/aug/25/muammar-gaddafi-libya-audio-speech-august-25-2011

[49] Tim Lister shares similar views in “Gadhafi’s demise and the Arab Spring.” (Lister (2011) http://www.articles.cnn.com/2011-10-21/world/world_gadhafi-arab-spring_1_yemen-and-syria-sidi-bouzid-arab-spring?_s=PM:WORLD.

[50] The ICISS developed the concept of R2P. As criteria, commitment to a humanitarian intervention, they require that there be circumstances of actual or apprehended: (a) “large scale loss of life” and (b) “large scale of ethnic cleansing”, whether carried out by killings, forcible expulsion, or acts of terror and rape. ICISS, The Responsibility to Protect (Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 2001).

[51] The frequent regime-led annihilation of civilians, in Kosovo and Rwanda (to name a few), the preeminence of state sovereignty came under scrutiny. In response, the ICISS came into being, and it offered guidelines for intervention and R2P.

[52] This resolution called for an arms embargo on Libya, and warned of possible repercussions given Qaddafi failed to heed the resolution. http://www.icc-cpi.int/NR/rdonlyres/081A9013-B03D-4859-9D61-5D0B0F2F5EFA/0/1970Eng.pdf

[53] “Strongly condemning what it called human rights violations by authorities, and abuses by other actors, in Yemen following months of political strife, the Security Council this afternoon demanded that all sides immediately reject violence, and called on them to commit to a peaceful transition of power based on proposals by the major regional organization of the Arabian Gulf.” http://www.un.org/press/en/2011/sc10418.doc.htm

[54] Nuclear Proliferation News. June 1st, 1995, via World Information Service on Energy: Uranium Project. www.antenna.nl/wise/433-4/brief&source

[55]Smith, Spencer. 1990. Nuclear Ambition: Spread of Nuclear Weapons 1989-1990. United States: Westview Press Inc. (p. 183).

[56] See John Wright (1982) for extensive details of Qaddafi’s relations with the LAS leaders, and diplomatic relations with the West.

[57] Unlike President Bashar of Syria who aligned himself with Russia and received air defense systems in case of a western-led military intervention https://www.stratfor.com/analysis/syria-what-prevents-us-military-involvement, Qaddafi did not have any alliances with either western or eastern diplomats.

[58] The Hilton Assignment was first discussed in a book by McConville and Seale in 1973. Also see, Hughs, Roberts. November 2011. “Who Said Gaddafi had to Go?” in London Review of Books. Pp. 8-18, Vol. 33 No. 22.

[59] Pan Am Flight 103, a Boeing 747-121 en route from London to New York was blown up over Lockerbie on December 21, 1988, leaving all 259 passengers on board the plane along with 11 Lockerbie residents dead. See Fitzgerald, Allistair. 2006. Air Crash Investigations: Lockerbie the Bombing of PANAM Flight 103. Mabuhay Publishing.

[60] Libyan forces moved into the strip around the end of 1972, setup an air base near Aozou guarded by ground to air missiles. (Biarnes, 1975). One alleged reason for this occupation was that the strip was thought to be rich in uranium deposits – U.S. intelligence later confirmed that Libya had acquired ‘yellow cake’ from the region in 1978.