Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Research Context

This dissertation concerns itself with the role of civil society in shaping development partnerships as an aspect of Indian foreign policy. India is one of the fastest growing economies in the world (Nobrega and Sinha, 2008). Over the last fifteen years it has witnessed a remarkable transformation of its domestic as well as international priorities. The country is now recognized as an ‘emerging donor’ (Chanana, 2009; Woods, 2008; Walz and Ramachandaran, 2011), with the Indian government successfully institutionalizing its official development assistance programme with the establishment of the Development Partnership Administration (DPA) division under the Ministry of External Affairs, in January 2012 (Republic of India, Ministry of External Affairs2015). Some estimates suggest the amount of foreign spending in the form of ‘aid’ flowing out of the country was close to $1.3 billion in 2013-2014 alone (Sharan et al, 2013). Given the potential it has to emerge as a leader in South-South Development Cooperation (SSDC) initiatives, it is important to evaluate the dynamics of cooperation and partnership in the Indian context. One of the ways to approach this is to look at how domestic forces interact with the realm of foreign policy in the country. The focus is on development partnerships as an aspect of development cooperation, however the two terms have been used interchangeably because the conceptual boundaries between ‘partnerships’ and ‘cooperation’ in the context of development are not quite as defined as one might expect them to be.

At the very outset, it is important to note that while civil society and development cooperation have been the subject of extensive academic as well as policy work in the past two decades, the precise relationship between the two has not received the attention it deserves. More specifically, in India the focus of civil society has largely been on domestic issues and the sector as a whole is yet to define its terms of engagement with foreign policy, an area more often viewed as best left to government agencies responsible for it. The focus of this dissertation is therefore to undertake an evaluation of the aforementioned relationship at a theoretical level by exploring civil society as an ideal or value in Indian development cooperation as well as empirical level, by exploring the dialogue between specific CSOs and the DPA.

India’s development cooperation has managed to receive some attention from academia, public opinion, the media, and the Indian Parliament, although the focus is quite recent in nature. Despite this, the precise role that the Indian public and civil societyplay in India’s development cooperation programme has been left largely unexplored. Chaturvedi et al. (2014) identify two primary reasons for this: first, foreign relations simply do not get the same amount of attention as domestic political, social and economic issues; and second, that apart from some notable exceptions such as India’s neighbours or the United States of America (USA), the subject of foreign relations has been relegated to a small group of elites within the government who continue to define India’s foreign policy based on their own conceptions of national interest. Moreover, it can be argued that any focus on foreign policy issues necessarily entails a two-way engagement process if non-state actors are to involve themselves. The government has a crucial role to play in encouraging public and civil society engagement on foreign policy and development cooperation issues, as well as sustain any interest that these actors initiate in the area as well.

1.2 Research Focus and Overall Research Aim

The focus of this dissertation therefore lies in the nature of the dialogue between the Government of India, specifically the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), and civil society organizations (CSOs). Public opinion shall be analysed as expressed through organizations that exist in the public sphere or the ‘civil society’ as understood in general terms. The concept of civil society shall simultaneously be problematized in subsequent sections, and the implications of the same on dialogue with the MEA shall be addressed.

This dissertation shall approach civil society as an actor in development cooperation along with the state, and attempt to discern the nature of the aforementioned dialogue in terms of each actor’s security needs. The theoretical framework thus developed will use the concept of ‘ontological security’ in order to explain existing civil society engagement in Indian development cooperation. The concept of ‘ontological security’ is an emerging theory in international relations that seeks to explain the foreign policy behaviour of states as guided by a moral basis that serves the state’s security needs. It is hoped that this framework will provide an adequate explanation for the type of CSOs that involve themselves and why they do, as well as how their involvement is perceived by the MEA.

The overall research aim of this dissertation is to deepen the understanding of civil society as a force within foreign policy-making and development cooperation in the South. For the purpose of this study, we look more closely at the dynamics in India’s foreign policy and development cooperation programme for two primary reasons:

- a) Although India is referred to as an emerging donor, India’s first bilateral development assistance agreement was with Nepal back in the 1950s (Srinath, 2013). The country has a long history of engaging with its neighbours in South Asia on development issues, and has truly emerged as a regional leader in SSDC over the past decade.

- b) Indian civil society, despite its historically difficult relationship with the Indian state, remains to be one of the most diverse in the world (Tandon and Mohanty, 2003) with NGOs, think tanks, trade unions, women’s groups and student movements lending their time and effort to issues of relevance to the citizens of India, as well as countries in South Asia and more recently, in Africa.

The study has various aspects to it, and two main research vehicles will be used to facilitate it: an in-depth review of the literature available on civil society and its participation in development cooperation, provided in the second section; and the exploration of civil society involvement as a function of the ‘ontological security’ needs of the state, discussed in the fourth and fifth sections. The third section contains the description of the data collection techniques used to collect relevant empirical data on the issue, as well as the method of analysis (i.e. theoretical framework) used in the study.

This dissertation will contribute to the field of international relations, and development policy making, by addressing gaps in the existing literature and pointing towards new areas that require academic and policy focus from researchers and practitioners alike.

The next section therefore, examines key debates as well as gaps in the literature available and relevant to the objectives of the study through three analytical aspects: the theorization of civil society, the roles and functions of CSOs in development cooperation and partnerships, and the conceptual basis of the SSDC framework.

Chapter 2 – Civil Society In Development Cooperation and Partnerships: An Analytical Approach

This section shall look at three analytical aspects of civil society involvement in development cooperation and partnerships: the theorization of civil society (part 2.1), the roles and functionsof CSOs in development cooperation (part 2.2), and the overall conceptual basis of the SSDC framework (2.3). The structure of this literature review as a whole aims to provide the reader with firm background knowledge upon which the theoretical framework of this study as well as upcoming discussions are based.

2.1 The Theorization of Civil Society

The concept of civil society has been championed by many as ‘the idea of the late twentieth century’ (Khilnani, 2001:11), although the origins of the term can be traced back to Romans (Parekh, 2004:14). The concept was reinvented in the 1980s in Eastern Europe and Latin America, and incorporated into discourse on international development in the 1990s (Glasius et al, 2004). Broadly speaking, Khilnani (2001) describes the West as interested in civil society primarily as a means by which public life can be revitalized given the traditional ‘boundaries’ of politics of the state and political parties, while the East is understood as engaged in a process by which the term itself is given “new currency” by intellectuals (Khilnani, 2001, pp.11-12). According to Sahoo (2013), the modern usage of the term can be divided into four broad conceptions, namely the system of needs, sphere of hegemony, realm of associations and social capital, and arena of public sphere. These perspectives shall function as conceptual lenses in our overall evaluation of the role of civil society in development cooperation.

In recent years, a significant body of work has been produced on the subject of civil society involvement in foreign aid and development cooperation. Within development economics, Fowler and Biekart (2011, p.5) characterise civil society as a “messy empirical category”. They also provide a list of various understandings of the term according to Glasius (2010), namely as social capital, citizens active in public affairs, non-violent action, fostering public debate, and counter hegemony. Van Staveren and Webbink (2012) summarise Fowler and Biekart’s interpretation of civil society as “normative, reflecting pro-social values and contributing to development” (Van Staveren and Webbink, 2012, p.11), similar to the view of World Bank economist Michael Woolcock (2011) and political scientists Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis (2002).

In India, the growth of civil society can be traced largely through three main phases identified by Sahoo (2013) which deserve mention: the period of Nehru (1947-1964) characterised by a civil society that was comprised of and controlled in its interactions with the state by elites; the regime of Indira Gandhi (1967-1977) in which a mass-based civil society is said to have emerged; and the Congress Government and Structural Adjustment Programme (1991-1997) during which India witnessed a dramatic rise in NGO activity and the professionalization of these NGOs.

The rise in the number of NGOs in India, along with other social movements and voluntary associations since the 1990s resulted in the term civil society entering public discourse on a broader level in India (Chandhoke, 2012). Early attempts to come up with a minimalist definition of the concept were motivated by the fact that the term itself had begun to be appropriated by all kinds of organizations in the country as a unifying principle (Dubochet, 2011). Tandon (2002), for instance, in one of the first attempts to define and outline a criteria for inclusion into the so-called ‘third sector’ said that “Civil society comprises individual and collective initiatives for common public good” (Tandon, 2002, p.32). According to him, “Only those associations, which affirm openness of entry and exist, and stand by universalist criteria of citizenship” should constitute civil society (Tandon, 2002, p.32). Similarly according to Jayal (2001), “As such, any association which excludes persons on the basis of ethnicity, class, or religious persuasion is clearly not a part of civil society” (Jayal, 2001, p.43-44).

However, there is little evidence in existing literature of a comprehensive attempt being undertaken towards the specific task of theorizing civil society in the context of Indian development cooperation. The term itself is understood in the context of development as consisting of diverse organizations and relationships, but little attention has been paid, for instance, to the use of the term as an ideal by the Indian government as well as other international entities. Furthermore, debates between the DPA and civil society have reinforced the idea that civil society as a concept can be convincingly represented by a select few civil society leaders armed with the intellectual sensibilities that fulfil the vision of the government’s perception of the sector. This no doubt is problematic, and deserves more attention from researchers as well as practitioners, as to why a certain conception of civil society is more favourable in the context of development cooperation between countries.

2.2 The Roles and Functions of CSOs in Development Cooperation

Various studies have been initiated by organizations such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canadian Council for International Cooperation (CCIC), the World Economic Forum (WEF), and Oxfam India on the role of CSOs in development cooperation, largely in the context of the delivery and effectiveness of aid and assistance.

The focus of the OECD for instance has been on the role of civil society in improving aid effectiveness, reinforcing the vision of the Paris Declaration of March 2005 which recognized CSOs as “potential participants in the identification of priorities and the monitoring of development programmes” (OECD, 2009, p.13). The organization’s focus on civil society in the context of aid effectiveness however has been specifically on CSOs and therefore is concerned more with institutionalized forms of civil society as agents of change and development. Canada is one of the few countries in the world that have actively tried to engage with civil society on development cooperation issues. A companion piece to the CCIC’s Strengthen Aid Effectiveness: New Approaches to Canada’s International Assistance, published as an issues paper in June 2001 actively approaches CSOs as “actors in the design, delivery and evaluation of development policy and programs” (CCIC, 2001, p.1). The CCIC has funded research that seeks to explore how CSO competencies can be harnessed in the formulation and implementation of their Official Development Assistance (ODA) programs. The WEF’s The Future Role of Civil Society published in January 2013 also alludes to the concerns of civil society leaders around the world regarding ways in which they can remain relevant and continue to impact global governance processes collectively (WEF, 2013, p.17), and in this regard CSO responses to development cooperation are crucial. Civil society has been recognized now as an important stakeholder in development-related foreign policy issues, especially civil society from middle income countries and the ‘rising powers’, India being one of them (Poskitt and Shankland, 2014; Shankland and Constantine, 2014).

A couple of studies supported by Oxfam Indiaalso identify the changing roles of civil society in middle income countries in the context of development (Dubochet, 2011) and engagement with the BRICS (John, 2012). These studies serve to form a conceptual basis upon which systematic case studies on civil society can be carried out, and as such shall be used over the course of this research as well.

Similarly, institutions like the World Bank have engaged in a categorization of CSO functions which is useful and can be applied to different contexts (in this case, India) in order to differentiate among CSOs. The World Bank identifies the following functions (Pollard and Court, 2005):

- Representation (organizations which aggregate citizen voice)

- Advocacy and technical inputs(organisations which provide information and advice, and lobby on particular issues).

- Capacity building(organisations which provide support to other CSOs, including funding).

- Service delivery(organisations which implement development projects or provide services).

- Social functions(organisations which foster collective recreational activities).

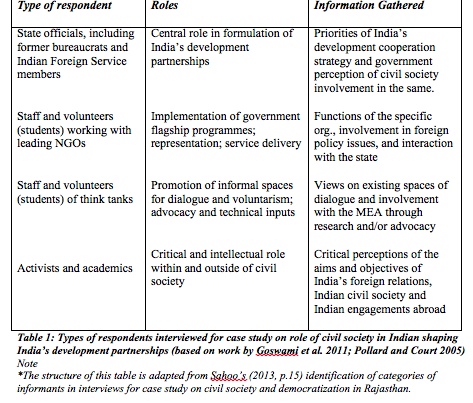

In the context of India, the literature discusses the changing roles of civil society, notable among which are: promoting participatory government and democracy, implementing government flagship programmes, promoting informal spaces for dialogue and voluntarism (although it can be argued that formal spaces of dialogue are increasingly playing a more pivotal role), and protesting against anti-people policies (Goswami et al, 2011).

Attempts have also been made towards developing a typology of CSOs, based on their aims and functions. One classification views Indian civil society as comprised of many types of organizations which are as follows: (i) Community-Based Organisations (CBOs), (ii) Mass Organisations, (iii) Religious Organisations, (iv) Voluntary Development Organisations (VDOs), (v) Social Movements, (vi) Corporate Philanthropy, (vii) Consumer Groups, (viii) Cultural Associations, (ix) Professional Associations, (x) Economic Associations and (xi) Others, including media and academia, although there is currently no consensus on whether media ought to be included as a part of civil society (Goswami et al, 2011).

The literature on the subject gives the sense that a lot of academic and/or policy effort has not been invested domestically in exploring how civil society could impact India’s development partnerships and cooperation programmes. Yet, on the positive side it is also true that some attention has been drawn to the subject in the past few years, especially since the establishment of the Forum for Indian Development Cooperation (FIDC) in 2013 by the Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS), the latter being an autonomous research think tank established with financial support from the Government of India. The FIDC is now recognized as a forum for policy debate and dialogue through which civil society in India has been able to make significant contributions (Moilwa, 2015, p.3).

Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA) in collaboration with RIS organized a workshop held May 2013 on India’s Global Development Presence and Engagement of Indian Civil Society, and the workshop report (PRIA, 2013) produced by PRIA is one of the key contributions to the literature relevant to this study. The workshop was attended by representatives from the DPA division of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, and civil society, and the report highlights the fact while both the DPA and civil society members are willing to engage in dialogue, certain concerns remain. One of them is ambiguity regarding what the specific aims and outcomes of Indian development investment abroad are, and what role they play in national diplomacy (PRIA, 2013, p.3). Government distrust of the “NGO sector as whole”, which impedes upon any effort to form a consultative apparatus (PRIA, 2013, p.3) is also brought up. Even if such an apparatus were to be formally institutionalized, questions remain as to what the precise role of civil society would look like. The report notes that while consultations with civil society have been initiated by the Planning Commission of India as well as the UN, its recommendations have not been taken seriously in the past. Thus, civil society is advised to remain cautious of its engagements with the DPA (PRIA, 2013, p.4). The report therefore establishes that the DPA on the whole views civil society as a space from where ideas can be sourced. However, it is unclear as to how keen it is on involving civil society organizations in the formulation of programmes and partnerships with other countries, as an actor and stakeholder in the process.

The PRIA workshop report also brings up the issue of what Indian civil society thinks its role in India’s development cooperation really is, and the consensus right now is that the sector as a whole is not sure of its precise role in the matter. This in part is due to the fact that there exists a vacuum in terms of intellectual engagement with foreign policy issues in the country (PRIA 2013, p.3). This is a contentious issue, and this study shall engage with it at an analytical level in subsequent sections.

Some new studies on the CSO-state relationship in India have been initiated, for instance by Mawdsley and Roychoudhury (2015, forthcoming) wherein the focus is on three different, but interconnected set of relationships between CSOs and the state, in the form of independent activists, critical engagers, and government partners that interact with the Indian state on development cooperation. This research can be viewed as speaking directly to the category of critical engagers, broadly categorised as sharing a common vision of stronger Indian civil society engagement in SSDC yet remaining critical of the some elements of the ‘official discourse’ around South-South cooperation. However, this research also views the CSO-state relationship as heavily influenced by the functional and operational aspects of CSO activity, an area that their research touches upon intuitively yet does not engage with directly. Nonetheless, emerging research in the area could benefit from the synergies arising between the analytical and explanatory approaches adopted by various scholars in the field.

However, given the dominant focus on CSOs, the existing literature on the subject fails to give adequate attention to the question of what type of CSOs have been received more positively by governments (particularly the ‘rising powers’) and organizations like the OECD, and whether functions ultimately determine the role played by CSOs. There is a similar lack of focus on the competencies that CSOs or indeed any civil society actor must possess in order remain relevant and important in the field of development cooperation. In this regard, while practitioners have the capability of shedding light on the real-time concerns of policy makers when they interact with CSOs on these issues, while researchers and academics might be able to contribute through the development of a specific taxonomy of CSO competencies which could be more useful to policy makers and governments.

2.3 The Conceptual Basis of the SSDC Framework

Chaturvedi et al (2014) and Wilson (2014) identify the ‘conceptual pillars’ upon which India’s idea of assistance is based, as part of the larger SSDC framework. They point out that many national level CSOs in India have supported the ‘common, sustainable, and socially just approach to international relations’ adopted by the country under the SSDC framework specifically, reflected in a growing motivation to become involved in development projects.

While there has been a widespread acceptance of the ‘principles’ upon which the contemporary SSDC framework is based, namely the ‘common, sustainable, and socially just approach to international relations’, this study shall approach them with caution. One of the reasons for this is that the evolution of the idea of progressive and new principles in the field of development cooperation has been uneven and does not apply uniformly to every player in the current SSDC architecture. It is worth noting that while there might be some foundational principles agreed upon by all Southern states in this regard, every emerging donor nevertheless applies them in their agreements in a manner contextually specific to their own interests. The idea that SSC and SSDC principles are different from that of traditional donors because they are based on an idea of mutual need and social justice needs to be problematized, especially in light of both China and India’s investments in land, in certain African countries.

Therefore, it is ultimately important to construct a framework that views civil society as a stakeholder in the process, with interests (dis)similar to that of governments and business communities. This however, does not mean reducing civil society engagement in development cooperation into a simple matter of means and ends. The field of development cooperation is a political space, involving actors whose actions are political to the extent that they involve the question of considering each country’s national interest. Civil society, therefore, must be considered a political as well as social being in its own regard with material as well as ontological needs similar to that of governments themselves, both in terms of its role in development partnerships between countries, as well as relationship with the state.

The next section of this study gives a detailed overview of ‘ontological security’ as the theoretical framework/methodology of analysis used in the study to explain and understand civil society involvement in development cooperation between India and its partner countries. It also briefly discusses the methods used in this study for the purpose of data collection and primary/secondary research work.

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

Part 3.1 will present an overview of the concept of ‘ontological security’ as the theoretical and methodological framework that shall be applied to the data collected for this research in order to achieve the overall research aim of this paper discussed in Part 1.3. Part 3.2 of this section will discuss the overall research strategy and provide an overview of the research methods employed.

3.1 Theoretical Framework: Ontological Security in Development Cooperation

The concept of ontological security is useful as an alternative to the traditional realist and neo-liberal approaches developed in the field of International Relations (IR) that have been used to explain development cooperation between states. The focus of these approaches has primarily been on power politics and physical security (realism) or national interest in cooperation and collaboration (neo-liberal institutionalism). Ontological security maintains that national interest is a key factor for states, however views state action as guided by the moral and self-identity needs of states (Steele, 2008; Kang, 2013).This research however, also concerns itself with the actions of civil society actors and uses ontological security as a framework that can help find points of similarity as well as difference between state behaviour and CSO behaviour in development cooperation.

Therefore, two broad analytical sections have been presented below, each addressing a key aspect of using ontological security as a theoretical and methodological framework for the purpose of this research:

3.1.1 Ontological Security in Theory

Although international relations (IR) scholars like Jef Huysmans(1998), Jennifer Mitzen (2006), and Brent J. Steele (2008)among others, have applied ontological security in their work, the concept was first introduced in the context of individual psychology by Anthony Giddens (1991). He defines it as “a sense of continuity and order in events, including those not directly within the perceptual environment of the individual” (Giddens, 1991, p.243). Individuals develop a certain sense of ontological security based on establishes “routines of various forms” (Giddens, 1991, p.44), as their self-identity needs to be “routinely created and sustained in in the reflexive activities of the individual” (Giddens, 1991, p.52). This sense of security is also bound up with the ‘biological narrative’ that individuals supply for themselves (Giddens, 1991, p.54; Kang, 2013).

In the context of world politics, the concept is discussed by Mitzen (2006) who defines it theoretically as “confidence and trust that the natural and social worlds are as they appear to be, including the basic existential parameters of self and social identity” (Mitzen, 2006, p.342; Kang, 2013, p.17).

Jef Huysmans (1998) adopts a ‘thick signifier analysis’ approach to the concept of security itself, and attempts to differentiate between ontological security as “mediation between chaos and order”, and daily security as “mediation of friends and enemies” (Huysmans, 1998, p.229). Security as a thick signifier implies an interpretation that “does not just explain how a security requires the definition of threats, a referent object, etc. but also how it defines our relations to nature, to other human beings and to the self” (Huysmans, 1998, p. 231). Therefore, ontological security for Huysmans implies the organization of social relations into a symbolic as well as institutional order through which a sense of self can be constructed and maintained.

When analytically applied to the state, a consistent sense of self built and maintained through a narrative, serves to “give life to routinized foreign policy actions” (Steele, 2008, p.3), as highlighted by Kang (2013) in the context of Korean development assistance. The novelty of ontological security as an international relations theory lies in its focus on morality, identity, and security as concepts that seldom exist in isolation of each other, and therefore an analysis of interlinkages between them is necessary.

3.1.2 Ontological Security, Foreign Policy, and the State

IR theory comprises of three broad perspectives for explaining state action: realism, which views state action as guided by self-interest; liberal institutionalism, which views state actions as guided by the structural norms and principles determined by regimes or institutions in the international arena; and constructivism, originally developed as an alternative approach to realism, which views state action as a function of the historical and social construction of ideas, rather than as an inevitable consequence of human nature. Wendt (1992) famously describes international anarchy as “what states make of it” (Wendt, 1992, p.395), in his work on social constructivism.

A leading concern in traditional IR theory, nonetheless, is the theoretical focus on the physical security of states (Kang, 2013). Given three different theoretical perspectives, each offers a new explanation for what motivates states to seek physical security in their international relations. On the other hand, ontological security as a theory developed primarily in the context of individual psychology (Giddens, 1991). It incorporates larger themes of anxiety and fear into its analysis of individual security, and therefore its application to international relations must necessarily involve an assumption that states are similar to people. This is one of the starting points in understanding foreign policy and the state through the lens of ontological security.

Kang (2013) provides an elegant overview of how Mitzen (2006) and Steele (2008) defend the application of ontological security to the state, as well as Steele’s subsequent criticism of Mitzen’s work as lacking a methodological basis. Two specific defences offered by Mitzen are of particular consequence to this research. First, it is argued that states are interested in preserving the national group identity, beyond the national “body” (Mitzen, 2006, p.352). If states lose their sense of distinctiveness as they undertake a continuous engagement with their ‘biographical narrative’ (Giddens, 1991), it would inadvertently threaten the ontological security of its members (Mitzen, 2006; Kang, 2013). This is important because “a stronger collective identity of the members of the state, will make the state stronger” (Kang, 2013, p.17). Second, a more practical defence of ontological security follows from the understanding that as a theoretical perspective, it helpful in discerning “macro-level patterns” as well as “organizing anomalies in current theory into an overarching analytical framework” (Mitzen, 2006, p.352; Kang, 2013). Steele’s defence of the concept moreover, recognizes states as comprising of state leaders with their own ontological security needs. However, the state as a single agent is differentiated from state leaders, and it is argued that leaders will consequently have a converged sense of security perspectives for the state (Steele, 2008, p.19; Kang, 2013), although this need not imply a convergence of individual security perspectives.

With regard to methodological aspects, or the question of how one can measure ontological security-seeking behaviours, Kang (2013) details a set of interrelated factors identified by Steele (2008). One of the factors concerns the biological narrative of the state, within which Steele argues that the narrative reflects what the state understands about its Self, how it is affected, and consequently what policies the state must concern itself with in different circumstances (Kang, 2013). Similarly, the factor of discursive framing by co-actors is also identified. This is an important contribution specifically in the context of research areas involving the behaviour of more than one actor or group of actors. It is argued by Steele (2008) that “what co-actors and the international community thinks or calls the Self would critically affect the ontological security of the Self” (Kang, 2013, p. 19).

The above discussion provides evidence of how the ontological security perspective has been applied to international relations quite successfully in recent years. However, academic work in the area has been dominated by regular comparisons with traditional IR theory, and the merit of ontological security has been explored in largely relative terms. While this is a useful approach, it nonetheless restricts the scope of a theoretical perspective because the referent object of analysis remains to be the state. The theoretical framework detailed above shall be applied in following sections in order to address this in two ways:

- Following from the state-centric perspective adopted in the literature, the role of civil society as an ideal in development cooperation shall be explored; and

- Departing from the state-centric perspective, the ontological security needs of civil society organizations working in development cooperation shall be discussed with relevant evidence.

The method of analysis adopted in this research is similar to the approaches discussed above in the sense that it surveys the ontological security needs of the state, as well as the needs of civil society organizations/associations which reflect a convergence of perspectives.

3.2 Research Strategy and Methods

Given that the overall research aim of this paper is to analyse the nature of the existing relationship between the Indian state and civil society on development partnerships in South Asia and Africa, the research methodology employed is qualitative and exploratory in nature. A combination of primary and secondary data is used in the research, with a focus on supporting existing research on the subject with new evidence as well as new methods of explaining and understanding the gaps identified in the critical assessment provided in Part 2.3. The objective of collecting primary data is to assess the priorities and opinions of those actors within Indian civil society as well as DPA division, who might be directly or indirectly involved with in Indian development cooperation, especially in the formulation of development partnerships.

The research strategy that will be used to achieve the overall research aim is a case study. What is a case study and why is it relevant to this research? The case study approach is generally recognized as an intensive approach. According to Cohen and Manion (1995), in a case study the researcher “typically observes the characteristics of an individual unit – a child, a class, a school or a community. The purpose of such observation is to probe deeply and to analyse intensively the multifarious phenomena that constitute the life cycle of the unit” (Cohen and Manion, 1995, p.106). This definition suggests that the purpose of a case study is to closely observe and analyse the behaviour of a specific group(s) within the particular context of the study. The case study approach was therefore adopted because of its “ability to deal with a full variety of evidence – documents, artifacts, interviews, and observations” (Yin, 1989, p.20). It facilitates the ambition of this research to analyse intensively the involvement of civil society in Indian development cooperation, in that it enables the researcher to undertake an in-depth study of specific aspects within the context established. The case study method has also been adopted due to the lack of case specific enquiries into the subject which represents a methodological gap in existing literature.

Qualitative data for the purpose of this research was collected through semi-structured interviews as the preferred method for primary data collection. The interview method was chosen because it provides maximum opportunity to interact directly with different stakeholders and individuals, and allows for comparisons between responses. The research relies on a small number of interviews, although the researcher has tried to ensure maximum diversity in the types of respondents chosen. Table 1 provides an overview of the types of respondents chosen.

The bulk of secondary data on the subject was collected in the form of reports, official government documents and press releases, journal articles and books. The existing literature was reviewed to understand the evolution of scholarship on the subject as well as its present limitations. Convenience sampling was used in order to select individuals for the interviews, since it allows the researcher to initiate contact with individuals who are viewed to be the most relevant voices on the issues under consideration.

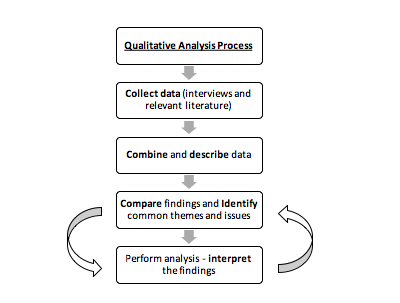

The data collected will be analysed in subsequent sections using the theoretical framework developed in the Part 3.1 of this section. The concept of ‘ontological security’, asmentioned, shall be applied to the findings. The qualitative analysis process for this case study can be summarised as follows:

There are however, limitations to this research. One foreseeable limitation of the case study is that its subject of analysis ultimately is restricted to only specific actors and/or organizations within Indian civil society. There is an associated logistical difficulty in getting data from different types of actors involved in the formulation of development partnerships, both from civil society and the Government of India. Another potential limitation is that the results of this study are particular to India due to the nature of the research strategy, and therefore cannot be generalized by the wider research community. Alternatively, the second limitation can be viewed as advantageous given that in order to understand a larger phenomenon, it is not always necessary for specific cases to have an element of generalization. Differences between various case studies can often serve to explain the behaviour of groups in a particular context better than similarities.

This research concerns itself more with satisfying the concepts of validity and reliability, rather than generalizability. It is valid because the case study has been conducted using a tried and tested research strategy, suitable data collection techniques have been employed, and the overall research methodology is both appropriate to the research as well as unique in its interpretation of findings. The research is reliable because due concern has been given to the research ethics: prior approval was sought from all interviewees before they were interviewed and the record of all interviews has been kept securely by the researcher. Similarly, secondary data used in the research has been accessed from trusted sources, with an emphasis given on peer-reviewed journal articles and reports/books published by reliable sources. Since the sampling method is non-random, the research does suffer from the issue of bias however given that the aim of the research is not one of generalizability, this problem does not significantly impact the overall reliability of the study.

Chapter 4: Civil Society As An Ideal In Indian Development Cooperation

Given the theoretical framework of ontological security with its focus on the moral and self-identity needs of different actors, it is possible to explore an alternative account of the role of civil society in development cooperation. This section discusses a key theoretical finding of this research: the role of civil society as an ideal in development cooperation. The approach adopted seeks to develop an account of the civil society as contributing to the biological narrativeof the Indian state, and in the process constructing an identity for itself. In doing so, it heavily draws upon the arguments of Mitzen (2006) and Steele (2008), however applies them in the context of civil society as opposed to the state.

We find that instead of viewing civil society as a “messy empirical category” (Fowler and Biekart, 2011, p.5), it is possible to theorize it as a concept that has beenunified in international development. One of the ways of theorizing this is to consider the role played by civil society as an ideal, or a value in the development narrative of states. In this sense, it can be argued that civil society is viewed as a unified entity despite its many contradictions and shortcomings.

The literature on the role of civil society in development cooperation provides little evidence of contemporary scholarship trying to approach the concept as a unified entity. Dr.Emma Mawdsley from the University of Cambridge points out that one of the reasons for this is that civil society by its very nature and designation, is a vastly diverse section of organizations (E. Mawdsley, personal communication, May 2015). This is true, however, there is some evidence to suggest that in their individual construction of identity and security needs, states have referred to civil society as a unified entity, by invoking it as an ideal in development cooperation. Although, this approach continues to use the state as the referent object of analysis, it is nonetheless a crucial departure point for the purpose of this research.

In theoretical terms, what does the construction of identity and security needs entail? A helpful starting point is to consider the ontological security needs of the Indian state itself. Dr. Mawdsley also distinguishes the priorities of countries like India and China from traditional, western donors by emphasising the role that morality plays in the conduct of their foreign relations (E. Mawdsley, personal communication, May 2015). Since the time of its independence in 1947, India has been influenced by the strong sense of moral efficacy that Nehru imbibed into the theory and practice of India’s foreign policy (Kennedy, 2011). India’s engagements with the Non-Aligned Movement are another instance of its involvement in the “moral critique of power politics” (Abraham, 2008, p.195). The moral underpinnings of the Indian identity in world affairs is consequently an evidence of an attempt to engage in the construction of a consistent self-identity, maintained through a biological narrative of moral progress, giving life to routinized foreign policy actions (Mitzen, 2006; Kang, 2013).

How is this focus on morality in the construction of identity and security needs relevant to our discussion of civil society? Onthe foreign policy and cooperation side of the issue, we have the consistent support to civil society being given by organizations like the UN, as well as governments. The focus given to civil society by the OECD, the CCIC, and the WEF have been highlighted in the literature review. Other evidence includes, the UN Secretary General’s Panel of Eminent Persons on Civil Society and UN Relationships discusses how the organization can improve its engagement with civil society, along with other stakeholders (United Nations, 2004). Similarly, the Government of Finland recognizes that “From the viewpoint of development cooperation, the essence is that efforts and support to strengthen civil society are aimed at the eradication of poverty and promote economically, socially and ecologically balanced sustainable development, in accordance with the UN Millennium Development Goals set in 2000” (Republic of Finland, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2010). Kumar Tuhin, Joint Secretary of the DPA in India, in a similar vein, has stressed on the importance of initiating a dialogue between the DPA and Indian civil society on development policy (PRIA, 2013).The consistent invocation of the term ‘civil society’, instead of a specific focus on a type of civil society actor, brings us to a critical juncture. Indeed, if civil society as an actor cannot be unified given the vastness of the concept itself, then what explains the consistent use of the term in the collective rhetoric of international development?

The term civil society, it can be argued, lends an aspect of morality as well as accountability to the actions of states, and other international entities. It continues to be invoked as a unified entity by states because in doing so, it transforms into an ideal which can legitimizes foreign engagements. Civil society, in other words, combines a state’s need to be morally secure about its actions. This is also true in the context of the SSDC framework which relies on the principles of mutual benefit, as well as social justice (Wilson, 2014). The function of civil society as an ideal or value in foreign relations represents Steele’s (2008) methodological argument about a state’s biological narrative. The invocation of the ideal reflects what the Indian state, more specifically, understands its role to be in the broader SSDC framework. It also influences the state’s perception of civil society in this regard, as well as the policies with which it consequently concerns itself (Kang, 2013).

The ontological security approach, in other words, explains the use of the term civil society as an ideal, and provides us with a way in which the concept has been unified by international actors. It must be kept in mind however, that the invocation of civil society as a unified entity or an ideal does not entail a disregard for its complexities on part of international actors, and neither does this analysis seek to support a simplistic reduction of civil society into a universalistic institution. Reports and publications, similar to the ones mentioned above, do attend to the task of breaking down civil society from its idealistic connotations into the practicalities of the concept itself. This is primarily because for the purpose of research and policy work, it is impossible to consider each actor within civil society comprehensively. Nonetheless, at the level of theoretical analysis, civil society continues to represent an ideal within the larger debates concerning the moral and ethical aims of development cooperation.

The above discussion has focused on an alternative theoretical dimension of civil society involvement in Indian development cooperation. The next section considers the empirical applications of the ontological approach in order to explore the construction of identity in India’s development partnerships in further detail, and identifies key features of the existing relationship between civil society and the state in Indian development cooperation.

Chapter 5 – The Construction Of Identity: Civil Society In India’s Development Partnerships

The theoretical approach discussed above, through which one can explain the transformation of civil society into an ideal in development cooperation, can also be applied to specific actors within civil society. The empirical findings of this research focus on civil society organizations or CSOs within Indian civil society, and their contribution to the formulation of India’s development partnerships. From the previous sections, two broad points are worth reiterating:

- Civil society is highly nebulous and offers no easy explanation of itself. Given the limitations of using the term in addressing the practicalities of the sector’s engagement with the state, it is important to focus research in the area on the type of actors relevant to development cooperation, in this case Indian development cooperation.

- It is also essential to note that while the SSDC framework has been differentiated from the approach adopted by traditional DAC donors, the principles upon which it is based are deeply connected to the national interest of non-DAC donors. National interest in the context of countries like India is expressed in economic, as well as geo-political terms.

Therefore, an analysis of the role of civil society in India’s development partnerships must essentially involve breaking down the ideal of civil society into workable spheres of material interest. It must be recognized that actors within civil society benefit equally from the state, just as the state benefits from their existence. Despite the invocation of civil society as a unified whole, as discussed above, the Indian state is nonetheless privy to the myriad of relationships that exist within Indian civil society.

The relationship between Indian civil society and the state on matters of development cooperation can be explored through two ontological security perspectives: the convergence of security perspectives, and the discursive framing by co-actors (Steele, 2008).

5.1 The Convergence of Perspectives

India’s development cooperation strategy is difficult to classify within the ‘development aid’ paradigm. Dr. Sachin Chaturvedi, Director General of RIS, has highlighted that SSDC is not focused on aid, as understood in the sense of traditional donor-recipient relationships. Instead, it comprises of five features: grants, technology transfer, trade, lines of credit, and investment (PRIA, 2013). India since 2008 has extended quota-free trade to least developing countries, as part of the larger South-South emphasis on engaging in “real partnership(s) for development” (PRIA, 2013, p.8). Recognizing the need for mutual conversations between the DPA and civil society, Dr. Chaturvedi also brings up the important question of whether Indian civil society is willing to develop its own indicators for South-South cooperation. The ability and capacity of civil society to contribute effectively to the work of the DPA is crucial to an analysis of its relationship with the latter, and in this regard it is useful to view civil society-state interactions as a continuum of legitimization. The more legitimate an organization is viewed to be by the state, the more likely it is to be able to lend a voice of accountability to the state’s actions domestically as well as internationally. It is also more likely to be recognized as an effective collaborator in the state’s international engagements.

Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the continuum of legitimization. Most civil society-state relationships exist on this plane; however it is important to note that it does not determine whether the recognition of an interaction comes from an actor within civil society, from the state, or from both. In the context of this research, legitimization is viewed as coming from the state in terms of whether it views an organization as credible enough to engage with.

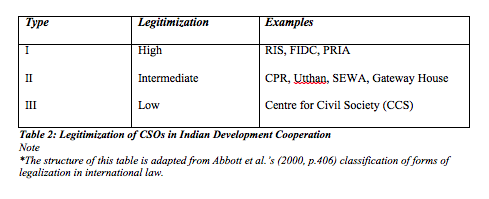

In the specific context of development cooperation, existing relationship between civil society and the DPA can be illustrated according to high or low degrees of legitimization, depending on the level of collaboration with the MEA (Table 2).

Table 2 illustrates three different types of legitimization of CSOs in Indian development cooperation. The degree of legitimacy has been inferred based on whether an organization has been expressly funded/recognized by the MEA (high), to whether it has engaged in aspects of India’s development partnerships with other countries either through service delivery, research or advocacy (intermediate), to organizations that have little or no association with the MEA concerning development cooperation (low). It must be noted that an organization that falls in the low category might be a CSO that does not engage in development cooperation issues as a matter of mandate and is therefore less likely to associate itself with the MEA. In this case, it is an instance of legitimacy which is not derived from the MEA, but might exist otherwise.

From Table 1, it can be inferred that some organizations enjoy greater levels of legitimacy from the MEA, as opposed to others. One factor involved in this differentiation is the specific function of an organization. The most crucial functions relevant to an association with the MEA appear to be: implementation of government flagship programmes (SEWA/Utthan), promotion of informal spaces for dialogue and voluntarism (RIS, FIDC), representation (SEWA, CCS), advocacy and technical inputs (CCS, CPR, PRIA, Gateway House, Observer Research Foundation (ORF)), and service delivery (Utthan, SEWA) (Goswami et al., 2011; Pollard and Court, 2005). It can be observed that Type I organizations which enjoy high legitimacy are also the ones exclusively supported by the MEA, while Type II and III are independent organizations which either provide a service delivery and advocacy element to the work of the MEA, or expressly concern themselves with research work that is deemed useful by the MEA.

Apart from organizational functions, the factor regarding government distrust of NGO sector (PRIA, 2013) determines where a specific civil society-state relationship lies within the continuum. In this regard, Neelam Deo, former Indian Ambassador to Denmark and Ivory Coast, and current Director of the research think tank Gateway House: Indian Council for Foreign Relations highlights in her interview that the MEA has been quite welcoming of research and policy work from independent organizations (N. Deo, personal communication, March 2015). This is evident in the establishment of the RIS with funding from the MEA itself, and the consequent creation of the FIDC by the RIS. With regard to how the MEA perceives the work of CSOs in general, Ms. Deo also believes that it is very need-based with the DPA inviting contributions from civil society only on matters which it believes need an input from external sources. The latter view is also supported by other respondents, particularly those working as staff and/or volunteers with CSOs. For instance, Mr. Amit Chandra, Senior Manager of the Academy division at the Centre for Civil Society in New Delhi (A. Chandra, personal communication, April 2015) points out quite straightforwardly that any form of dialogue is always going to be influenced by the existing structure of power between the MEA and civil society, and a democratically elected government cannot be unduly pressurized into accepting what CSOs have to offer at all times.

The findings of this research, nonetheless, point towards a convergence of perspectives among organizations across the continuum of legitimization, especially among organizations enjoying an intermediate to high level of legitimacy being in favour of a greater role for civil society in the formulation of India’s development partnerships. This convergence however, involves individuals and groups within civil society, and represents an interesting parallel between the convergence of perspectives between state leaders and the state as a single agent, highlighted by Steele (2008) and Kang (2013). For instance, organizations like the RIS and PRIA have actively taken up the initiative to open up spaces for dialogue between the DPA and civil society members through workshops and seminars. The role of these CSOs in shaping India’s development partnerships is also determined by their own ontological security needs, similar to that of the state as discussed in the previous section. This is an interesting trend owing to the fact that these organizations operate with different missions individually, and might also differ along their operational functions. However, they nonetheless represent a section of Indian civil society that wishes to expand its role in India’s international engagements with other countries. A participation in the same lends a sense of continuity in the construction of an organization’s self-identity as a voice within civil society that is arguing for a moral and accountable Indian state as an international actor. An ontological approach thus justifies the involvement of CSOs as an aspect of the simultaneous construction and maintenance of the biological narrative of CSOs and the Indian state.

5.2 The Discursive Framing by Co-Actors

National self-identity in international politics can be constructed in a number of ways. Steele (2008) identifies the discursive framing by co-actors as an important element in the construction of ontological security needs of the state. According to Hall (1999), “To analyse any system one must designate actors and their interaction. The analytic ontology that results from doing so will very often determine, and limit, the range of phenomena one will be able to analyse” (Hall, 1999, p.12). This is evident in the literature on the evolution of foreign aid as an instrument of national interest, with its focus on the observable behaviour of industrialized states as a key indicator in the setting of contemporary development assistance priorities (Hook, 1995). This behaviour has been historically presented as “an opportunity to establish the linkage between national interest and foreign policy” (Hook, 1995, p. xii). However, in the context of South-South cooperation, the overlapping of foreign aid with development assistance breaks down.

Within the SSDC framework, co-actors in the process of the formulation of development partnerships can be identified as the following: the state, the private sector (businesses and other for-profit entities), civil society, and the international community. These actors are not different from the ones present in traditional donor relationships in the North, however the nature of the relationship between these actors is, needless to say, quite distinctive. The SSDC framework is dominated by official government to government interaction (Constantine and Shankland, 2014), and the contribution of other actors in the processes set by governments is determined by the priorities of the concerned state machinery. In this context, any discursive framing by co-actors falls heavily in favour of the interests of one actor, namely the state.

Specific to the institutional landscape discussed in this paper, it can be argued that the need for a discursive dialogue between the DPA and civil society has been recognized as important by representatives from either side (PRIA, 2013). Although there is significant ambiguity surrounding what the nature of such a dialogue would be and how it is to be operationalized into practice, past interactions between the two actors have nonetheless resulted in:

- Knowledge Sharing between CSOs and the State: The emerging focus on civil society as an indigenous source of knowledge that can guide the Indian state in formulating development agreements with its partner countries, particularly in South Asia and Africa. Given the experience of Indian civil society in actively engaging with various developmental issues ranging from poverty to water management and microfinance, inputs from civil society in the form of technical research as well as service delivery can prove to be very useful for the MEA. In this regard, organizations like VANI (Voluntary Action Network India) can provide a pluralist (combing and joining of power resources for the people) as well as educationalist (spiritual support for democratic functions arising out of long term participation in citizen networks) function as civil society actors (Hadenius and Uggla, 1996).

- Contextualization of Civil Society: A context specific idea of Indian civil society has evolved, which is relevant to the interests of the Indian state vis-à-vis development cooperation. The present emphasis within the DPA, it seems, is more towards research and policy analysis as well as service delivery through CSOs, resulting in support to those actors that reflect a more elite and intellectual organizational focus (civil society participation in the workshop organized by PRIA in 2013 is one example). It nonetheless serves to contribute to the construction of India’s own biological narrative within the broader framework of foreign and development assistance. Emerging donors like India, although united by their engagement in a new form of assistance, continue to differ in the application of the so-called ‘SSDC principles’, “reflecting the independent prerogatives of each” (Hook, 1995, p.4). The role of Indian civil society in this regard is necessarily distinct from Brazilian or Chinese civil society. However, the evolution of this distinctiveness in meaning also reflects the dominance of a specific set of voices within Indian civil society. Participation of CSOs in any discursive dialogue, apart from being influenced by the process of legitimization as discussed above, is also determined to a large extent by access to financial resources. Although research in this area has made some progress, there is still scope for identifying the patterns in CSO funding in India, particularly funding of development NGOs and think tanks. Progress in this area might also help illuminate whether government mistrust of foreign-funded NGOs in India is a matter of where the funds originate from or a more complex dynamic between the exchange of cultural and moral ideas across borders.

- Emphasis on Ethics and Accountability: The critique of certain aspects of India’s international engagements, reflecting the moral continuity individual actors in Indian civil society seek for themselves even as a simultaneous convergence of perspectives is taking place. For instance, one report suggests that since 2008 approximately 1.2 million hectares have been acquired by Indian enterprises (Rebello, 2013). The process of land acquisition in African countries like Ethiopia, Mozambique, and Tanzania has also been identified as lacking transparency and local consultation (Cotula, 2012). The portion of investments undertaken directly by the Indian government is unclear, and so is the extent to which CSOs have directly concerned themselves with the issue. Nonetheless, criticism has been forthcoming, and it represents a positive trend towards an increasing measure of accountability in India’s foreign engagements. To what extent such criticism can influence expressly DPA-driven partnerships is difficult to predict. Capacity building and impact evaluation have been suggested as potential pathways to enable the DPA to track and coordinate investments being made by Indian enterprises globally.

Discursive framing between civil society and the DPA as emerging co-actors in the formulation of India’s development partnerships, therefore, is a complex and evolving process. Analytically, the result of the existing process has been recognition of the potential contribution CSOs can make. In terms of the type of CSOs, a functionalist approach is clearly more useful than others since it enables the identification of actors depending on the kind of contribution they can make to the work of the DPA. The above discussion has broadly looked at some of the more methodological aspects of civil society involvement in Indian development cooperation, and the next sub-section shall conclude the chapter by providing a defence of Indian civil society as an ‘arena of public sphere’, originally introduced by Jürgen Habermas (1989).

5.3 Civil Society in Indian Development Cooperation: An ‘Arena of Public Sphere’?

In modern usage, three conceptions of civil society are identified by Sahoo (2013): system of needs, sphere of hegemony, realm of associations and social capital, and arena of public sphere. System of needs is associated with Hegel’s views on the distinction between civil society and the ‘political state’ which were different from that of the contractarians, focusing instead on man’s material needs as the basis of civil society. Sphere of hegemony refers to a particularly Gramscian view of civil society which identifies civil society as a sphere of freedom in which the capitalist state continues to exercise hegemony. Realm of associations and social capital attends to specifically liberal understandings of civil society, with Tocqueville’s distinction between political and civil associations in society, and consequent contributions by Fukuyama (1995) and Putnam (1993) for whom voluntary action is a source of ‘social capital’.

While each of these conceptions is an elegant approach to the study of Indian civil society, they nonetheless fail to capture its present role in the formulation of India’s development partnerships and the framework upon which its overall development cooperation strategy is based. The fourth conception of civil society, namely arena of public sphere, is arguably the most explanatory in this regard for a number of reasons. Habermasian public sphere, according to Sahoo (2013), “belongs to the same theoretical family of civil society, which provides a common platform for the representation of common interest in the public” (Sahoo, 2013, p.27). The focus of the public sphere, therefore, is on differentiating the opinion of bourgeois educated individuals from that of others (normative considerations and collective prejudices) (Sahoo, 2013). Habermas (1989) also argues that a strong public sphere can act a system of checks and balances on the domination of the state in society. Civil society as an arena of public sphere in Habermasian thought comprises the collective wisdom of the educated classes in society.

The approach developed by Habermas has received criticism for being based on the perpetuation of existing inequalities of status in society (Sahoo, 2013; Fraser, 1990). This is an important caveat. The empirical findings of the research, as highlighted in previous sections, suggest that civil society involvement in the work of the DPA in India is currently limited, but has the scope of transforming into a more comprehensive dialogue between the two actors. The research concerns itself with CSOs and finds that a functionalist approach is suitable for the classification of types of CSOs that have been or are currently involved with the DPA. We find that CSOs focused on the service delivery dimension are sought for their experience and expertise in implementing programmes as well as engaging in advocacy. Similarly, think tanks and research organizations are also beginning to invest themselves in a dialogue with the MEA, but such organizations also tend to have an inherent bias towards contributions from the educated classes owing to the nature and quality of work they are mandated to do. Organizations like the RIS which are expressly supported by the MEA, as well as Gateway House, ORF, and CPR which situate themselves in the field on the basis of the expertise and analysis they can provide, are distinctively dependent on the ‘collective wisdom’ of the educated classes. The expertise they draw from practitioners, academics, even volunteers is nonetheless very specific and detail-oriented. There is also a recognition among these organizations of their own limitations when it comes to dialogue with the DPA.

Public opinion harnessed through the dialogue with CSOs has the potential to enhance the work of the DPA. It has been established however, that CSOs currently engaging in a dialogue with the DPA represent a very small section of Indian civil society, mostly the educated classes. This research therefore views civil society in Indian development cooperation as ‘an arena of public sphere’. It finds that inputs from civil society towards the formulation of India’s development partnerships reflect the ideas and interests of a very small section of the public, comprising individuals as well as groups that have the capacity to mobilize around technical expertise and field experience. While this research does not present a normative defence in favour of this emerging role of civil society, future research on the subject can definitely benefit from doing so.

Chapter 6: Conclusion

Civil society involvement in development cooperation is endorsed and encouraged by international organizations, as well as governments. Within the SSDC framework, it is recognized as a crucial step towards the achievement of the principles of mutual benefit and social justice that serve as conceptual pillars of the framework. As an emerging donor, India has already institutionalized the coordination of its development partnership activities through the establishment of the Development Partnership Administration. Furthermore, the setting up of the RIS through funding support from the Ministry of External Affairs has been received positively, especially since the formation of the FIDC as a platform for greater interaction between the MEA and members of civil society organizations.

The lack of case specific enquiries into the nature of the civil society-state relationship among countries involved in SSDC, specifically the rising powers or the BRICS nations, has been the prime rationale behind the conduct of this individual case study on the role of civil society in shaping India’s development partnerships. The study has identified the key aspects of SSDC as:

- The current SSDC framework operates almost exclusively on a government-to-government basis, with the state functioning as the main actor in the formulation of development partnerships.

- Civil society involvement, however limited it may be, is nonetheless a growing area of concern among governments who wish to explore competencies and knowledge that exists outside of the ambit of the state machinery responsible for managing development cooperation.

Using ontological security as a theoretical framework, this case study on India has contributed to the growing scholarship on the subject by presenting civil society participation as a factor that serves the construction and maintenance of the moral and self-identity needs of the state, as well as CSOs. Engaging in development cooperation enables a sense of moral continuity in a state’s foreign policy actions, with recent studies such as the case study of Korean development cooperation by Kang (2013), discussing the aspect in great detail. This study has focused on how civil society contributes as an additional element in this regard, functioning as an ideal in Indian development cooperation and functioning as a unified entity in the current discourse on international development. It has also focused on how civil society participation in development cooperation serves the individual ontological security needs of organizations in Indian civil society, evidenced through a convergence of perspectives and the discursive framing by co-actors of their individual and collective self-identity.

The study relies on a continuum of legitimization to explain the basis of the relationship between CSOs and the MEA, and identifies types of CSOs currently engaged in Indian development cooperation using a functionalist approach. Therefore, CSOs viewed as more legitimate by the MEA by virtue of their functional mandates are found to be those engaged in: implementation of government flagship programmes, promotion of informal spaces for dialogue and voluntarism, representation, advocacy and technical inputs, and service delivery. Broadly however, there is an overarching focus on research and advocacy, and service delivery among the CSOs that are currently shaping substantive aspects of India’s development partnerships with other states. Despite the existence of different individual functions, we can observe a convergence of perspectives among these CSOs on the subject of increased civil society participation and/or a measure of indirect involvement with the MEA, in the case of India.

Apart from a convergence of perspectives, the discursive framing by co-actors is also identified as a factor in the construction of identity. The term is deceptive in the context of the civil society-state relationship in India, given the ambiguity surrounding the scope of the current dialogue between CSOs and the MEA. Nonetheless, an interaction has been initiated and has contributed to a growing emphasis on knowledge sharing between CSOs and the state, a contextualization of civil society vis-à-vis Indian development cooperation, and ethics and accountability.

The research has a number of limitations, most notably the lack of comprehensive field work and data on the subject. This study has been conducted primarily through an analysis of published journal articles, reports, and government documents, and has relied on interviews to gain a further insight into the perception of a few relevant actors in the field. It is hoped that future research on the subject can use this case study as a framework upon which to build upon newer ideas and incorporate evidence in the form of better data, both qualitative and quantitative.

Nonetheless, a few recommendations can be made for future research on the subject, particularly pertaining to the resolution of existing ambiguities anda strengthening of the role of civil society in Indian development cooperation. The question of government mistrust towards civil society organizations, particularly those which depend significantly on foreign funding, still remains. How can government mistrust be mitigated in favour of greater dialogue and debate regarding Indian investments (by the state as well as private enterprises) made abroad? What capacities does the DPA require to increase coordination and monitoring of CSOs engaged in Indian development cooperation? Similarly, how can CSO engagement over foreign policy be increased in the Indian context? Is there any transnational incentive-driven strategy that can be adopted in this regard? These are some of the issues that require a creative synergy between commentators from academia, civil society, and the Indian state.

It is difficult to imagine a conceptual landscape in which civil society can be easily grasped or simplified. However, if we begin our enquiries by acknowledging the immense transformational capacity that exists in civil society as an ideal as well as a group of actors, we are in a position to achieve the goal of effective assistance and impact in international development cooperation.

References

Abraham, I. (2008). From Bandung to NAM: Non-Alignment and Indian Foreign Policy, 1947–65. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 46(2), 195-219.

Bowles, S. & Herbert, G. (2002) Social Capital and Community Governance, The Economic Journal 112, pp. F419-F436.

CCIC (2001). Civil Society and Development Co-operation: An Issues Paper. Canadian Council for International Cooperation.

Chanana, D. (2009). India as an emerging donor. Economic and Political Weekly,44(12), 11-14.

Chandhoke, N. (2012). Whatever Has Happened to Civil Society? Economic & Political Weekly, 47(23), 39.

Chaturvedi, S., Chenoy, A., Chopra, D., Joshi, A., & Lagdhyan, K. (2014). Indian Development Cooperation: The State of the Debate. Rising Powers in International Development IDS Evidence Report No. 95. Brighton: IDS.

Cohen, L. & Manion, L. (1995) Research Methods in Education, London: Routledge.

Cotula, L. (2012, February 22). Analysis: Land Grab or Development Opportunity. BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-17099348

Dubochet, L. (2011). The Changing Role of Civil Society in a Middle-Income Country: A Case Study From India. Oxfam India Working Paper Series OIWPS XI. Oxfam India.

Fowler, A., & Biekart, K. (2011) Civic Driven Change: a Narrative to Bring Politics back into Civil Society Discourse. Working Paper no. 529. Institute of Social Studies: The Hague.

Fraser, N. (1990). “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy”, Social Text, No. 25/26, pp.56-80.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity, New York: The Free Press.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Glasius, M. (2010) Dissecting Global Civil Society: Values, Actors, Organizational Forms, Working Paper 14. The Hague: Hivos.

Glasius, M., Lewis, D., & Seckinelgin, H. (Eds.). (2004). Exploring civil society: Political and cultural contexts. Routledge.

Goswami, D., Tandon, R., & Bandyopadhyay, K. (2011). Civil Society in Changing India: Emerging Roles, Relationships and Strategies. New Delhi: Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA).

Habermas, J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, trans. T. Burger and F. Lawrence.

Hadenius, A., & Uggla, F. (1996). Making civil society work, promoting democratic development: What can states and donors do?. World development,24(10), 1621-1639.

Hall, R. B. (1999). National collective identity: social constructs and international systems. Columbia University Press.

Hook, S. W. (1995). National interest and foreign aid. Lynne Rienner Pub.

Huysmans, J. (1998). Security! What Do You Mean? From Concept to Thick Signifier. European Journal of International Relations, 4(2), 226-255.

Jayal, N. G. (2001) “Situating Indian Democracy”, in Jayal N. G. (ed.), Democracy in India, Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 1-49.

John, L. (2012). Engaging BRICS: Challenges and Opportunities for Civil Society. Oxfam India Working Paper Series OIWPS XII. Oxfam India.

Kang, M. (2013). Explaining Korean Development Assistance. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Oxford: United Kingdom.

Kennedy, A. (2011). The international ambitions of Mao and Nehru: national efficacy beliefs and the making of foreign policy. Cambridge University Press.

Khilnani, S. (2001) ‘The development of civil society’, in Kaviraj, S., & Khilnani, S. (Eds.). Civil society: history and possibilities. Cambridge University Press.

Mawdsley, E. & Roychoudhury, S. (2015). Civil Society Organisations and Indian Development Assistance: emerging roles for commentators, collaborators and critics. Forthcoming.

Mitzen, J. (2006). Ontological security in world politics: state identity and the security dilemma. European Journal of international relations, 12(3), 341-370.

Moilwa, T. (2015). Realising the Potential of Civil Society-led South-South Development Cooperation. ISD Policy Briefing Issue 84. Brighton: IDS.

Nobrega, W., & Sinha, A. (2008). Riding the Indian Tiger: Understanding India–the World’s Fastest Growing Market. John Wiley & Sons.

OECD (2009). Better Aid Civil Society and Aid Effectiveness. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Parekh, B. (2004). ‘Putting civil society in its place’, in Glasius, M., Lewis, D., & Seckinelgin, H. (Eds.). (2004). Exploring civil society: Political and cultural contexts. Routledge.

Pollard, A. & Court, J. (2005).How Civil Society Organizations Use Evidence to Influence Policy Processes: A literature review. Working Paper 249, Overseas Development Institute, London.

Poskitt, A. and Shankland, A. (2014) Innovation, Solidarity and South-South Learning: the Role of Civil Society from Middle-income Countries in Effective Development Cooperation, Brighton: IDS, http://cso-ssc.org/synthesis/