London and New York are primary centres for both finance and the art market, indicating the continuing power of place. Both cities have become havens for wealth, wealth that has poured into the art market, and sometimes into the newer practices of art investment. Under what can be termed the financialisation of art, we can see the rise of a new industry sector that further knits together the art market and financial services, explaining the growth of art investment and its supporting industries, and highlight the enabling role of geographic location (e.g. Coslor 2011). Financialisation is a topic of some interest today, in the wake of the financial crisis, but for a number of years researchers have been observing shifts toward profiting from financial channels, as opposed to trade or production, and the growing roles of financial actors, motives and institutions (Epstein 2006).

What is interesting in studying the financialisation of art is the difficulties and work required for financialisation to proceed, as market specificities challenge a project of quantification and flattening. In this sense, we might understand the art investment community as seeking to comprehend art in the same ways as other forms of financial investing, both conceptually and by creating similar financial investment vehicles: although artwork does not look quite look like stocks and bonds, new quantification methods allow the art market to appear quite recognisable for people used to looking at private equity. For individuals with financial market expertise, and particularly for institutional investors, this means that art price indices, information providers and dedicated art investment funds can help to facilitate institutional investment. Institutional investors are important actors in financial markets: they comprise insurance companies, investment companies, pension funds, or trust departments who invest large sums in financial securities markets (Scott 2003: 191).

New York and London as Centres of Art and Finance

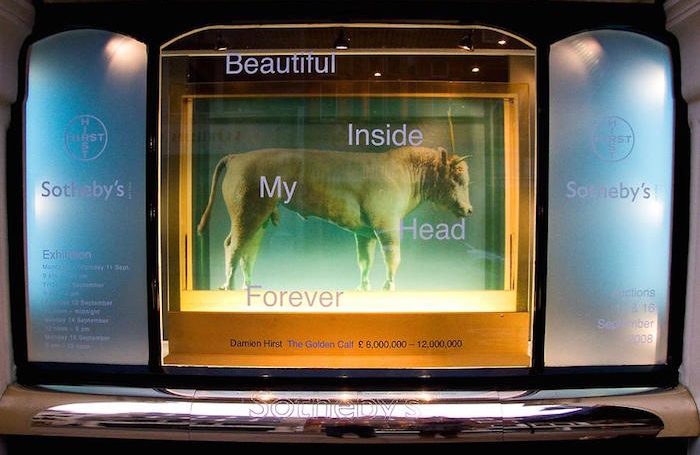

While art investing activity is taking place in a number of cities, it is most prominent in London and New York, the key centres of both the Western art market and financial markets. New York is home to a global elite. From its origins as a Dutch colony to the development of Wall Street, New York has always been a stronghold of American finance. Today, New York is also a well-established place to set auction records. Over the last few years, as art consultant Abigail Asher points out, “a new class of buyer has entered the market and they’re prepared to pay staggering sums for trophy pictures”.

In contrast, London has seen a different surge of money, mostly pouring in from the east. As in New York, property prices have soared, as Russian and other wealth has moved into the capital city. According to estimates, London is home to 44.8% of the United Kingdom’s high net-worth individuals, a group defined as anyone with more than $1 million in investible assets, excluding the primary residence. Moreover, that number is growing, pushed by what the some term the globalisation of wealth, and “drawn by a combination of low taxes, historical ties and a geographical location that makes the city attractive for people doing business in Eastern Europe, Asia and the Middle East”. This surge in money and growth in high net worth individuals is a key part of the interest in art, both traditional art buying and art as investment. There is a “new community of international collectors who have London as their base, and they feel comfortable buying here,” according to Cheyenne Westphal, chairwoman of contemporary art for Sotheby’s in Europe, who is based in London.

In both cities, high net worth individuals and others are driving investment, along with institutional investors, who have different criteria and motives. According to an interview with a London art investment fund, buying art is attractive as a diversification tool, because it has typically not been correlated to traditional markets in stocks and bonds. Wealthy clients especially are risk averse and seek uncrowded investments, i.e. stable, less volatile assets that are not in an inflated price bubble.

The Financialisation of Art

Cultural economics researchers typically view fine art as offering two sorts of value to owners, the investment value, which is a monetary return, together with art as a consumption good with aesthetic yields or a psychic rate of return. Yet with the growing financialisation of art, we can identify a different category of art speculators – or art investors – who are no longer interested in the ‘aesthetic yield’, though paradoxically, must also have the detailed knowledge of the value of artwork that is more typical of a connoisseur (Chong 2005: 89). The ongoing work of economists, investment professionals, and others helps to make art recognizable as an investment in ways that were not typical of the art market in the past (Coslor 2011). Here, art is being conceptualised as an investment class, with a focus on overall price trends, rates of returns and other properties (e.g. Mei and Moses 2002; Pesando 1993). This makes the pure art investor into a rather unique type, and can thus be differentiated from the more typical buyers of ‘passion investments’ who collect valuable art the way they buy coins or expensive cars, obviously capturing some consumption benefits.

The use of artwork as a financial investment thus joins together several groups of interested parties with different methods and motives, as is also the case with collectors (Aslop 1987: 70-1). One might, for example, see art as a financial asset with returns comparable to stocks and bonds, “like a normal investment,” except that the only dividend is the enjoyment of having a picture on your wall (Bolger 2006). Alternatively, one might see art and antiques as holding value to diversify and stabilize an investment portfolio. Whatever the case, this investment interest has historical roots: there have been various periods in American and European history where financiers have perceived artwork as a more stable form of investment than other commodities (Steiner 2001: 213). But the current trend in art investment is a more recent innovation, one facilitated by academic interest from economists, growing auction price data, numerical price indices, and typically using institutional and private investment fund structures as vehicles. This form of investing took hold in the 1960s and 1970s, and corresponds to technological shifts that have made sophisticated numerical art pricing services possible, among other types of investment strategies, together with portfolio diversification interests.

An important development to this end is the ability to conduct numerical comparisons. For example, the Mei-Moses Fine Art Index—which tracks the sale prices of art auctioned in New York City since 1875—explicitly compares the financial returns of art to those of stocks and bonds. A key early example for modern, strategic investment in art is the British Rail Pension Fund. Beginning in the early 1970s, it was Britain’s first (and it is believed only) large pension fund to enter the collectibles market at the time. From 1974 to 1999, the fund invested in more than 2,400 works of art of various types to supplement more conventional investments and serve as a hedge against inflation, which was extremely high in Britain in this period. But while enjoying returns above 11%, when the British press discovered that the fund was “gambling pensioners’ money on artworks,” the pension fund pulled the plug on its art investment activities.

Since then, other investment funds have bought works of art to include amongst their assets for the purposes of diversification. There are several types of investors who are putting money into artwork, but my focus is on firms, rather than individuals. In this area, the key distinctions are whether the firms are directly buying artwork, and if so, how much of their investment portfolio is in art. This differentiates dedicated art funds from other types of institutional investors who are not specialized in artwork. The latter may either begin to buy art directly, typically with the help of an art specialist, or may channel some portion of their investment monies into one of the specialized art funds for profit or diversification purposes.

Art investment funds that have only works of art among their assets are a fairly new innovation, and I would argue, represent another step in making art like other financial investments. Similar to the more familiar REITs, (real estate investment trusts), art funds allow an investor to buy art in security form, that is, a share of a diversified pool of artwork, where the individual is not in contact with any of the problems of the physicality of art, storage, security and maintenance. This securitisation provides distance from the work, which makes fund shares like traditional investments, because the buying decisions for which pieces of art to buy are informed by the advice of specialists, with a management structure focused on strategically buying and selling, allowing investors in funds to focus exclusively on the financial returns.

The underlying organisational structure of these art funds is typically that of a private equity fund, sometimes called a private investment fund. A private investment fund is generally exempt from United States federal securities regulations and is included under the label of hedge funds, with the criteria of either having less than 100 investors or that the member investors have substantial funds invested elsewhere. Clients (or members) of the art funds are typically some mixture of high net worth individuals and institutional investors, which can even include other investment funds.

A variety of firms cater to the growing interest in art investment, with a mixture of different offerings in each one, from art market information services, to collection management, to full investment funds like the Fine Art Fund. Successful funds are typically started by groups with the unique combination of art market and financial experience, due to the idiosyncratic, unregulated and highly mediated nature of the art market. Many of the art funds opened by firms without significant expertise in artwork have failed (e.g. Horowitz 2011: 180-1), perhaps because the art market requires such a high degree of insider knowledge.

Running a successful fund thus requires considerable planning, due to the nature of the art market and specific qualities of art as an asset. Aside from tax issues, artwork engenders high costs for storage and insurance, which are much higher than for financial assets. Buying art also involves the risk of making poor investment choices which are subsequently difficult to undo, because collectibles cannot be disposed of rapidly, making them a relatively illiquid investment. Finally, there are uncertainties about valuation and the possible returns on the investments. Artwork generates no income and the return comes entirely from capital appreciation. For example, given the costs of holding these assets, Blake suggests that the gross return on collectibles has to “exceed that on financial assets by a sizeable margin before it dominates the return on financial assets” (Blake 2003: 426).

Understanding Art Investments and the Market

One issue for art funds and other potential investors is that art is a potentially difficult investment: unique and difficult to compare, difficult to aggregate and track trends, and difficult to quantify numerically in a systematic fashion, although there are efforts in this area. These issues come on top of the dealer-mediated and unregulated workings of the art market, which make art difficult to conceptualise as a financial investment for several reasons.

Cultural economist William Baumol (1986: 10-11) has identified five key factors that differentiate works of art from traditional financial securities: uniqueness, ownership structure, frequency of transactions, the availability of price information, and the efficiency of the market. Uniqueness has to do with the physical nature of artwork: while stocks from the same company are homogenous, works of art are imperfect substitutes, not the same even if they are by the same artist. This relates to the second factor, because in Baumol’s view, with unique artworks, an owner has a monopoly, while stock ownership is a collective structure, with different shareholders who can act as independent and competitive traders. A key difference with art is that while stock trades are frequent, art sales are not, and also have high transaction costs. Moreover, stock prices are public, and easily available, while the price of artwork can be difficult to determine—the details of private sales not necessarily disclosed to outside parties. Finally, Baumol suggests that the theory of efficient markets does not necessarily apply to works of art, because while the equilibrium price of a stock is known, the existence of private art sales means we may not make the same assumption for art (see also Chong 2005).

Additional differences between traditional securities and works of art are highlighted in the way that different styles and periods of art possess differing market patterns. One important category of art used for investment is that of Old Masters paintings – i.e. masterpieces by the most famous European artists from circa 1350 to 1800 – which some call the “blue chip” of the art world, meaning a painting that is likely to be a safe bet, similar to the idea of blue chip stocks, which are stocks for companies that are leaders in their fields and in strong financial standing. This translation of terms between traditional financial investments and artworks is one way to make the new market more understandable to new art investors, through a comparison to something one already understands.

Turning away from the abstraction of art price information we can also see distinct similarities in the economic geography of where art investment funds and information providers are located. I believe that it is no accident that many are found in the key art and finance centres, given the consolidation of other specialized services in global cities. Many of the online price information providers are headquartered in New York and London, with other firms in Paris and Luxembourg. A similar geographic distribution is seen with the auction houses, as wealthy collectors tend to prefer to see artworks in person before bidding. Despite growing tools, such as art price indices, there is still an advantage for people and firms that are highly embedded in the art market, physically and socially close to other firms. Although we live in an age of virtual markets and buying behaviour, the geography of the art market is still important.

The advantages of proximity to informal market knowledge relate to the particular structure of the art market. Not only is speculation generally opposed (Velthuis 2005: 209-224), the opaque and embedded nature of the traditional art market still works more like Geertz’s bazaar economy, where information search cost are high, and buyers navigate this market through relationships with trusted sellers (Geertz 1978: 30-31). Going back to the model of the bazaar economy also shows why a social network model of market activity must be combined with the idea of a geographically situated industry cluster, at least if we are to understand the art market. Firms that want the best and fastest access to the privileged sales information of the traditional art market, and perhaps now the emerging art investment activity, need to be able to access people they know in galleries, museums, and the collector’s circuit.

Conclusion

Despite the global span of the art market and new forms of information technologies allowing sophisticated analysis, quantification, and global reach, the art market is still highly local in key ways. Art world players still decamp to New York and London for the key sales, exhibitions and art fairs. One still profits from word of mouth information that can often only be gathered in person. In analytical terms, there is geographic and social network embeddedness that can provide an informational advantage. As with the dual nature of the simultaneously locally-situated and globally reaching financial markets (Knorr Cetina and Bruegger 2002; Sassen 2001), the art market is now both globally dispersed and also concentrated into key cities, with strong concentration in New York and London. The insider knowledge, uniqueness properties of artworks and market features resist simple financialisation, meaning that the financialisation project is challenged. Rather than being stopped, the result is a form of financialisation that is not detached from social and economic life, but one entwined with the specificities of the market.

These findings also have more practical implications, suggesting that potential investors cannot simply rely upon art market information providers with facts and figures, at least not as a primary decision-making tool, as more expertise is required. Given the situated nature of information in this unregulated market, individual and institutional investors that want to add art to their portfolios and lack the close access to art markets are probably better off using art consultants or investing in specialised art funds. At the same time, given the unique qualities of art and the art market, it is also wise for most of us to follow the advice of gallerists and buy what we like, so that we may capture the “aesthetic dividends” of consumption, regardless of monetary value.

References

Alsop, J. (1987) The Rare Art Traditions: The History of Collecting and Its Linked Phenomena. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

Baumol. W. (1986) “Unnatural Value: Or Art Investment as Floating Crap Game”, American Economic Review, 76:10, 10-11.

Blake, R.W. (2003) Pension Schemes and Pension Funds in the United Kingdom. Oxford University Press.

Bolger, J. (2006) ‘Is It Just Art, or Is It Investment?’ The Times (17 April 2006).

Chong, D. (2005) Stakeholder Relationships in Contemporary Art, Robertson, I. (ed.) Understanding International Art Markets and Management. London: Routledge.

Coslor, E. (2010) “Hostile worlds and questionable speculation: Recognizing the plurality of views about art and the market”, Research in Economic Anthropology, 30, 209-224.

Coslor, E. (2011) Wall Streeting Art: The Construction of Artwork as an Alternative Investment and the Strange Rules of the Art Market. University of Chicago Press.

Epstein, G. (Ed.) (2006) Financialization and the World Economy. Edward Elgar.

Geertz, C. (1978) “The Bazaar Economy”, American Economic Review 28: 30-31.

Horowitz, N. (2011) Art of the Deal: Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market. Princeton University Press.

Knorr Cetina, K. & U. Bruegger, “Global Microstructures: The Virtual Societies of Financial Markets”, American Journal of Sociology, 107, 905-950.

Mei J. & M. Moses (2002) “Art as an Investment and the Underperformance of Masterpieces”, American Economic Review, 92, 1656-1668.

Pesando, J. (1993) “Art as an Investment: The Market for Modern Prints”, American Economic Review, 83, 1075.

Sassen, S. (2001) The Global City: New York, London and Tokyo. Princeton University Press.

Scott, D. L. (2003) Wall Street Words: An A to Z Guide to Investment Terms for Today’s Investor. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Steiner, C. (2001) “Rights of Passage: On the Liminal Identity of Art in the Border Zone”, in Myers F. (ed.) The Empire of Things: Regimes of Value and Material Culture. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press.

Velthuis, O. (2005). Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art. Princeton University Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Compromising US Energy Security for International Oil Market Stability

- Chile and the Overcoming of Neoliberalism: Countering Authoritarianism and the Self-Regulated Market

- Latin American Critical Economic Thinking and the Labor Market

- Reinforcing Environmental Degradation With Market-Based Sustainability Schemes

- The Art of Diplomacy: Museums and Soft Power

- Teaching International Relations as a Liberal Art