To find out more about E-IR essay awards, click here.

—

On July 14th, 2015, Iran reached the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPA) with the European Union and the P5+1, which includes the United States, China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and Germany (Gupta, 2015). The agreement aims to limit Iran’s nuclear program to peaceful purposes. This historical breakthrough came after months of negotiations, and it was not reached without great controversy inside the U.S., Iran and around the world.

Iran has been isolated politically and economically since its Islamic Revolution in 1979. The U.S. imposed bilateral sanction on Iran, while the United Nations began a series of sanctions on Iran since 2006 on violations related to its nuclear file. The history of US-Iran relations is filled with antagonism and hostility (Jones & Ridout, 2012). Both the United States and Iran have used grandiose and harsh rhetoric to describe the other. President George W. Bush placed Iran as part of the ‘axis of evil’, while Iran’s Supreme Leader Khomeini called the U.S. the ‘Great Satan’ (Jones & Ridout, 2012). Since Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, there had been no direct communication between the U.S. and Iranian Presidents (Nikou, 2015). The question arises then, how were the U.S. and Iran able to initiate talks to form this deal? Undoubtedly, the factors that led to reaching the Iran nuclear deal are numerous, but this paper aims to focus on the role of one specific actor: The Sultanate of Oman. Oman’s geographic location, unique foreign policy and political will allowed it to play an important mediating role, particularly in facilitating the initial secret meetings between the U.S. and Iran to reach a nuclear agreement.

Seen as a national security priority, the U.S. has long placed the Iranian nuclear file on top of its foreign policy agenda. President Barack Obama promised that his administration would prevent Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons, and reaching the P5+1 deal will definitely be one of his administration’s most notable legacies (Phillips, 2015). Exploring Oman’s mediating role in facilitating the initial U.S.-Iranian talks reveals the importance of understanding Oman’s diplomacy and how it can aid the U.S.’s strategic goals in the Persian Gulf and the Middle East.

This paper is divided into three sections. The first section will expand on how Oman became the U.S.’s backdoor to Iran. It will explore some of the secret meetings Oman hosted, and reflect on some of the motivations that led Oman to pursue this mediatory role. The second section will analyze the pillars of Oman’s foreign policy and diplomacy. Some of these pillars include neutrality, autonomy, discretion, and maintaining a balance of power. The third section will reflect on what Oman’s diplomacy means for the U.S.’s foreign policy engagement in the region. One of the key observations about Oman’s role in facilitating the Iran nuclear deal negotiations is the important role small states can play in solving complex issues through their diplomatic capital and political will.

1. A Backdoor to Iran

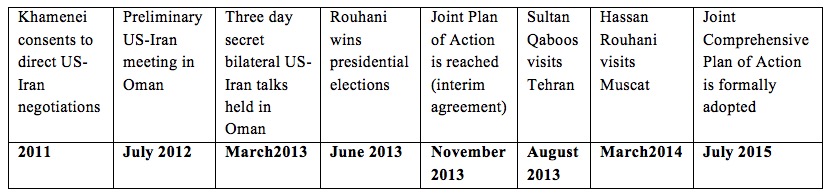

Table 1: Timeline of important events that relate to Oman’s mediating role in the Iran deal.Source: (Rozen, 2015) (Pourmohammadi, 2015).

A. Khamenei Gives the Green Light

Rozen (2015) argues that the national interests of both Iran and the U.S. drove the two countries to pursue a deal while the individual characteristics and competencies of each nation’s leader also played an important factor. Undoubtedly, the election of Rouhani accelerated the pace of the Iran nuclear talks. Rouhani presented himself as a moderate with the political will to engage actively on the nuclear program issue. In addition to an opportunity to reboot Iran’s relation with the West, Rouhani was accountable to an Iranian public watching him closely to see if he was going to fulfill his campaign promises. It is important to note that evaluating the actual nuclear deal itself and whether it will achieve its intended objectives is an important question, but it is beyond the scope of this paper.

Although progress in negotiations was only made after Hassan Rouhani was elected President in June 2013, Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei gave authorization to conduct secret talks with the U.S. in 2011. Khamenei gave the green light after Oman’s ruler, Sultan Qaboos, offered to be a mediator for direct US-Iranian talks.

One report indicates that Secretary of State, John Kerry- then chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee- presented the idea to Qaboos, who welcomed it and agreed to facilitate the meetings (Gupta, 2015). The Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei gave a speech in June 2015, confirming this:

“The Americans themselves asked for these negotiations and their proposals date back to the time of the tenth [Ahmadinejad presidency] administration. So, the negotiations with the Americans began before the arrival of the current administration.They made a request and chose an intermediary. One of the honorable personalities in the region [Qaboos] came to Iran and met with me. He said that the American president had called him, asking him to help. The American president said to him that they want to resolve the nuclear matter with Iran and that they would lift sanctions. Two fundamental points existed in his statements: one was that he said they would recognize Iran as a nuclear power. Second, he said that they would lift sanctions in the course of six months. Through that intermediary[Qaboos] , he asked us to negotiate with them and to resolve the matter. I said to that honorable intermediary that we do not trust the Americans and their statements. He said, “try it once more” and we said, “very well, we will try it this time as well.” This was how negotiations with the Americans began.” (Khamenei, June 23 2015)

In this statement, Khameniei refers to Sultan Qaboos as the ‘honorable mediator’. This indicates a level of mutual respect between the Sultan and the Supreme Leader. This also means that they shared a relatively ‘amicable’ relationship that gave the Sultan direct access to the Supreme Leader. As will be further discussed in section two, Oman has historically maintained good diplomatic relations with Iran. A relationship that favors long-term interests over “short-term ideological considerations”( Jones & Ridout, 2012, p. 178). Even after the 1979 revolution, or the controversial re-election of Ahmadinejad, Oman has been able to balance its relation with Iran and its strategic alliance with the U.S.

B. Secret Talks in Oman

As stated above, Qaboos urged the Supreme Leader to consider initiating talks, and when Khamenei expressed his mistrust of the Americans, Qaboos responded: “”try it once more”. However it took about a year to conduct the first preliminary meeting in July 2012. The meeting was held in Oman, representatives on the U.S. side included Jake Sullivan, deputy chief of staff to Hilary Clinton, who was Secretary of State at that time, and Puneet Talwar who was the National Security Council’s senior director for the Persian Gulf (Rozen, 2015). The second meeting was held in 2013 after the re-election of Obama. It was also held in Oman, and lasted for three days. In this meeting representatives on the U.S. side included William Burns, who was Deputy Secretary of State, and on the Iranian side, Ali Khaji who was Deputy Foreign Minister and Ali Akbar Rezaei, head of the North America office at Iran’s Foreign Ministry (Rozen, 2015). As former Iranian President Hashemi Rafsanjani stated in a speech on August 4th, 2014:

“A few months prior to the [2013] elections in Iran, high-ranking regime officials agreed that there should be negotiations with America. Before this, an [Iranian] team had been sent to Oman in light of a message from Sultan Qaboos, and two lengthy meetings were held [there]” ( Savyon, Carmon, & Mansharof, 2015, p. 1).

Oman’s back channel to Iran was kept a secret, especially from Oman’s Gulf allies. Discretion is a key characteristic of Oman’s diplomacy. This is captured perfectly in a statement made by the Omani Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sayyid Badr bin Hamad Al bu Saidi:

“In the space between the big states, the major powers, both regional and global, we have room for manoeuvre that the big states themselves do not enjoy. We can operate without attracting too much attention, conduct diplomacy discreetly and quietly” (Jones and Ridout, 2012, p.7).

Interestingly, when Rouhani ran his campaign on the promise of improving Iran’s economy by reaching a nuclear deal, he was not aware that Khamenei had already given the green light to then president Ahmadinejad and his Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Salehi. Salehi stated to an Iranian newspaper: “when Rohani learned about the details of the talks, he couldn’t believe it”(Esfandiari, 2015, p.1).

Oman took due diligence to maintain the secrecy of the meetings, hence little is understood about all the exact details of what went on in the meetings and visits. However, the important point to highlight is that Oman’s mediation worked. This leads to the next section, why was Oman motivated to mediate the negotiations?

C. Oman’s Stake: Why was Qaboos interested in an Iran Deal?

Taking on a mediating role is a reflection of Oman’s foreign policy, as will be discussed in greater detail in section two. However, one can argue that two factors motivated Oman to work towards limiting Iran’s nuclear program. The first is national and regional security, and the second is making diplomatic and economic gains.

National and Regional Security

Along with Iran, Oman manages the Strait of Hormuz, which is one of the world’s most important transit points for oil. It connects the Persian Gulf with the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea. In 2011, 20-30 percent of oil traded worldwide came through the strait (U.S. Department of Energy, 2012). It would not be in Oman’s favor to have a nuclear Iran, indeed, a nuclear warfare in the Persian Gulf would not be in anyone’s favor.

Oman is not oblivious of the possible dangers of Iran and Saudi Arabia’s regional contest for influence, which has manifested in Iraq, Syria and most recently in Yemen. Oman’s five Gulf neighbors Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates all view Iran with suspicious, and a possible economic, political and ideological threat. Like its Gulf allies, Oman recognizes the need to be cautious of Iran’s regional reach, but Oman chooses to respond to this threat differently. It chooses to be less alarmed at the grandiose sectarian rhetoric that circulates in the region. It also sees de-escalation of hostilities as a strategic security priority. Its approach puts forth the premise that you cannot achieve a balance of power without ‘constructive engagement’ (Al-Khalili, 2009). According to Al-Khalili (2009) Oman has been pursuing a “dual-track policy towards Gulf security” (p. 109) by forming strong defense capabilities and also strengthening its security alliance with the U.S.

Halting Iran’s nuclear program could also help prevent a nuclear arms race in the Gulf. Saudi Arabia has made a number of statements ‘threatening’ that it would also develop a nuclear program if Iran was able to militarize its uranium enrichment program (Sanger, 2015). Although it is debatable whether any Gulf State has the ability to develop nuclear weapons, or how much time and scientific capacity it would take, it is certainly in Oman’s favor to prevent such a prospect.

Diplomatic and Economic Capital

The Iran-Oman-U.S. diplomatic axis is a relationship in which all three parties can benefit. Iran and the U.S. wanted to negotiate a deal, and Oman, which shares good ties with both of them, wanted to strengthen those ties by offering its mediation. This diplomatic effort can translate into direct economic gains for Oman. As indicated in table 1 above, Sultan Qaboos and president Rouhani have exchanged visits where cooperation in the energy sector was cited as a major objective (Pourmohammadi, 2015).

An illustrative example of these economic opportunities includes two gas pipeline projects, which if successfully completed, would boost Oman’s trade and energy sectors. The first is an Iran-Oman gas pipeline. Since 2005, Oman had been trying to import gas from Iran. In fact, it signed a number of preliminary agreements for the pipeline project, but the economic sanctions and pressure from the U.S. never allowed the project to materialize (Shah, 2015). Now that the Iran nuclear deal has been signed, this gives Oman a golden opportunity to pursue the project. The pipeline will cost $1 billion, which will come from Oman and in return, it would share profits made from the sales. Iran and Oman may even form a jointly owned company to sell the gas in the international market and share the profits (Shah, 2015). The second project is a $ 4.5 billion pipeline connecting Iran to India via Oman. In September 2015, Indian companies conducted a series of negotiations indicating the project is under serious consideration. If completed, this would make Oman a regional gas hub, and increase trade connections between the Persian Gulf and India (Cihan News Agency, 2015).

Shah (2015) asks an important question: “where does Oman and Iran’s pipeline leave Saudi Arabia?” He argues that these pipeline projects may benefit Oman’s economy, but it comes at a possible risk. From the vantage point of Saudi Arabia, Iran is its biggest rival in the region. If Iran manages to strengthen economic ties with Oman, then this constitutes a blow to the Saudis. Further Saudi Arabia’s global market share in oil and gas exports may be affected by Iranian exports if and when Iran is able to.

Moreover, Oman shares a strong security alliance with the U.S. and it receives some military from the U.S. funding (Katzman, 2015). After the deal, the U.S. might choose to strengthen its security arrangements and increase its military aid to Oman. The next section will move on to explore the pillars of Oman’s foreign policy.

2. Oman’s Foreign Policy Pillars

Jones and Ridout (2012) argue that Oman’s diplomacy has four main principles. First, focus on long-term geostrategic interests. Second, refrain from sectarian or ideological strife. Third, aim for consensus. Fourth, affirm tolerance of other peoples and cultures, which is a remnant of Oman’s cosmopolitan historical legacy. Jones and Ridout point out that these principles are perfectly aligned with Oman’s officially stated foreign policy principles as shown in Oman’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs website:

- “The development and maintenance of good relations with all Oman’s neighbors

- An outward looking and internationalist outlook, as befits Oman’s geographic location and longstanding maritime traditions

- A pragmatic approach to bilateral relations, emphasizing underlying geostrategic realities rather than temporary ideological positions.

- The search for security and stability through cooperation and peace, rather than conflict” (Oman’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015)

Neutrality

This section will explore examples that illustrate some of Oman’s foreign policy characteristics. The first pillar of Oman’s foreign policy is a deep commitment to respect sovereignty. It tries to remain neutral and not take sides, especially when it comes to the internal matters of a country. Oman has a precedent in not interfering in regional conflicts. In the Iran-Iraq war in 1980-1988 Oman declared its neutral position when its Gulf neighbors were pouring money to support Saddam Hussien against Iran (Ma, 2014).

Even when there is a major conflict, such as the Syrian civil war, Oman opted not to completely cut diplomatic relations with Damascus (Cafiero, 2015b). At Oman’s invitation, Walid Moallem, Syria’s Foreign Minister visited Muscat and met with his Omani counterpart Yusuf Bin Alawi on August 6th, 2015. The stated objective of the visit was to discuss ways to end Syria’s conflict. Whether or not Oman will play a role in mediating the Syrian conflict remains an open question. However, this visit signals Oman’s willingness to use its diplomatic capital for different regional issues (Cafiero, 2015b).

Oman’s most recent neutral stance was refusing to join the Saudi led coalition in Yemen, which launched a military attack on the Houthis and their allied militias (Cafiero, 2015a).

When asked about his country’s stance in Yemen, the Omani Foreign Minister Yusuf bin Alawi stated that “Oman is a nation of peace”, and that “we cannot work on peace efforts at the same time we would be part of a military campaign” (Cafiero, 2015a, p.1). Oman has in fact attempted to hold negotiations with the Houthis and presented a seven-point peace plan, but so far those efforts have failed (Cafiero, 2015a). This leads to the second characteristic of Oman’s foreign policy, which is autonomy; Oman maintains its neutrality even when it means going against the wishes of major powers like the Saudi Arabia and the U.S.

Independence and Autonomy

When asked about the U.S.’s dual containment policy, Sultan Qaboos stated, “Iran is the largest country in the Gulf, with 65 million. You cannot isolate it” (Al-Khalili, 2009, p.103). When the U.S. decided to invade Iraq, Oman expressed its objection to the invasion, albeit not to the extent that it prevented the U.S. from using its military facilities in Oman to launch attacks (Al-Khalili, 2009). In the Gulf Cooperation Council, Oman is known for its objections to participate in military action. When Bahrain witnessed a large domestic uprising, Oman refused to take part in the joint Peninsula Shield Force that was sent to strengthen Bahrain’s regime. Moreover, when Saudi Arabia was pushing for a Gulf Union, Oman refused the proposal and threatens to end its membership in the GCC if such a proposal was implemented (Jones & Ridout, 2012). One element that has helped Oman maintain its independence is it’s unique religious identity. Oman’s Ibadi majority population allows it the unique position not to choose between the Shi’i and Sunni ‘camp’ (Jones & Ridout, 2012).

Balance of Power

‘Zero-problems’ with neighbors is a term used to describe Turkey’s foreign policy, this term can be applied to Oman as well. Oman has sought to maintain relations with all its neighbors. This includes Iran throughout its political transformation. As mentioned above, when asked about the dual containment policy, Sultan Qaboos stated, “Iran is the largest country in the Gulf, with 65 million. You cannot isolate it” (Al-Khalili, 2009, p.103). This statement reflects Oman’s pragmatism towards Iran. Moreover, Jones and Ridout (2012) explain that after the 1979 revolution Oman’s view was that “Iran was still Iran” and managing the Strait of Hormuz was still a shared geostrategic interest regardless of who was in power. What is highlighted in this remark is that Oman views its relationship with Iran on a long-term basis, and this has served its national interest well.

Discretion

Jones and Ridout (2012) argue that Oman’s diplomacy prefers discretion to maintain credibility. This is most evident in the way Oman handled the secret U.S.-Iran meetings. Oman realizes the value of discrete diplomacy, which allows it to ‘maneuver’ its place in the space between powerful states as stated above by the Omani Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sayyid Badr bin Hamad Al bu Saidi.

3. What This Means for the U.S.

What does Oman’s discrete diplomacy mean for the United States? It illustrates that the Sultanate of Oman holds regional and global importance, particularly in helping to maintain peace and security in the Persian Gulf and the Middle East at large. Oman seeks de-escalation of conflict. From a U.S. foreign policy perspective, Oman is a strong regional security ally (Al-Khalili, 2009). It hosts a U.S. Air Force, offers mediation of regional crises, and has freed a number of American hostages in Iran and Yemen.

U.S.-Omani trade relations can be traced to the 1800s, while Oman’s strategic alliance with the U.S. was solidified with the signing of an access agreement in 1981 (Al-Khalili, 2009). This allowed the U.S. to establish a major U.S. Air Force in Oman. This base has been critical for the liberation of Kuwait and the U.S.’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The U.S. base also serves the U.S.’s national security goal of maintaining the flow of oil by strengthening the security of the Strait of Hormuz (Jones & Ridout, 2012).

As mentioned, Oman is a strong security ally to the U.S. The country spends a significant percentage of its budget on developing its military, and a huge percentage of its weapons purchases come from American companies. In 2014, Oman spent 11.8 percent of its total expenditures on the military (World Bank, 2015), while in 2012, military expenditure constituted 35 percent of government spending (Valeri, 2014). When Secretary of State John Kerry visited Oman in 2013, he gave the final approval for a $2.1 billion deal for the U.S. manufacturer Raytheon to supply Oman with THAAD (Theatre High Altitude Area Defense system) “the most sophisticated missile defense system the United Stated exports” (Katzman, 2015, p.10).

Furthermore, Oman was one of the few countries that did not cut ties with Egypt when it signed its peace treaty with Israel. Oman also welcomed establishing relations with Israel, “in December 1994, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin visited Oman” and “by 30 September 1995, Oman became the first Gulf Arab state to have officially established trade relations with Israel” (Al-Khalili, 2009, p.113). However, the election of Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996 in Israel changed the direction of these relations, especially with the failure of the peace process and the advent of the first Palestinian intifada in 2000, most ties were severed by then (Al-Khalili, 2009). If there are future initiatives to resume a serious and effective peace process for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Oman’s willingness to engage with Israel in the past may prove be a huge asset to the U.S. for such an initiative.

Lastly, Oman has consistently used its diplomatic channels to help free Americans held hostage in Iran and Yemen. The three American hikers Sarah Shroud, Shane Bauer and Josh Fattal were arrested and detained in Iran in 2009 (Rosenberg & Fahim, 2015). The Sultan helped release Shroud in 2010 and Bauer and Fattal in 2011. More recently in September 2015, Oman has also helped free two Americans taken hostage as a result of Yemen’s civil war (Rosenberg & Fahim, 2015). Rozen (2015) argues that Oman’s successful mediation to free the three hikers in 2011 displayed Oman’s ability to bring results. This encouraged the U.S. to rely on Oman to mediate its negotiations with Iran for the nuclear deal (Rozen, 2015).

After Qaboos?

One concern that is relevant from a U.S. foreign policy perspective is the question of succession in Oman. Since Oman has been an important ally and diplomatic asset, it is relevant to ask whether or not the ruler that succeeds Qaboos will continue in the same direction. Sultan Qaboos holds absolute power; he is the head of state, “Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, and Minister of Defense” (Arslanian, 2013, p.8). Qaboos has no children and has not publicly named an heir. Grappo (2015) explains that on paper the succession process seems straightforward, but it has not been implemented before. The Royal Family Council has three days to agree on a new ruler after the death of the old one. If the council is not able to reach a decision, Sultan Qaboos has left a sealed letter naming a successor (Grappo, 2015). One report explains that possible successors include Assad bin Tariq Al Said, the Sultan’s personal representative; Shihab bin Tariq, a retired commander, and Haytham bin Tariq, the Minister of Culture (Dokoupil, 2012). Regardless of who succeeds Qaboos, they will face the challenge of gaining domestic legitimacy and maintaining Oman’s strategic diplomacy. Only when Oman’s new ruler takes power, one would be able to determine whether or not Oman’s foreign policy making is centralized in the hands of a few people, or institutionalized in a way that assures continuity when current decision makers are replaced by new ones. Finally, it can be argued that since Oman’s foreign policy has been fruitful for Oman’s national and regional goals, then any successor would be compelled to follow the same policy direction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper has examined Oman’s role in facilitating the Iran nuclear deal negotiations. It is in the U.S. interest to maintain its strong alliance with Oman. Oman’s unique foreign policy, which depends on pragmatism, neutrality, discretion and autonomy, has served the Sultanate well. It has also served the U.S. well in reaching the P5+1 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Exploring Oman’s discrete diplomacy and its role in facilitating the Iran deal negotiations also reveals an important observation: ‘diplomatic leverage’ may prove a more valuable asset than military capabilities in the international arena. This gives small states power to navigate international relations in a way that bigger and stronger states may or may not be able to emulate. Sultan Qaboos has been able to maintain a delicate balance of power. However, his policy has alienated the Sultanate from Saudi Arabia. What Oman presents as neutrality, is seen by Saudi Arabia as alignment with Iran. Saudi Arabia views the nuclear deal as a serious blow to its regional power. Furthermore, as Shah (2015) explains, Saudi Arabia will not welcome the idea of Iran presenting itself as a key economic partner in the energy sector for the smaller Gulf States, as in the case of the Oman-Iran pipeline project. Finally, as Ma (2014) suggests, diplomacy that comes from small states with deeply rooted ties such as Oman, may prove more effective in solving complex issues compared to pouring millions of dollars in military aid.

Bibliography

Al-Khalili, M. (2009). Oman’s foreign policy: Foundation and Practice. Westport, Conneticut: Praeger Security International.

Anthony, J. D. (1995, November 15). Oman: Girding and guarding the Gulf. Retrieved December 2, 2015, from National Council on U.S.- Arab Relations: http://ncusar.org/publications/Publications/1995-11-15-Oman-Girding-and-Guarding-the-Gulf.pdf

Arslanian, A. H. (2013). The Sultanate of Oman: Sons and Daughters. Digest of Middle East Studies, 22(1), 8-12.

Ayatollah Khamenei . (2015, June 23). Ayatollah Khamenei Official English Website. Retrieved December 2, 2015, from Leader’s speech in meeting with government officials: http://english.khamenei.ir/news/2088/Leader-s-speech-in-meeting-with-government-officials

Cafiero, G. (2015a, May 7). Oman breaks from GCC on Yemen conflict. Retrieved December 2, 2015, from Al-Monitor: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/05/oman-response-yemen-conflict.html#

Cafiero, G. (2015b, August 17). Oman’s diplomatic bridge to Syria. Retrieved December 3, 2015, from Al-Moniter: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/08/oman-diplomatic-bridge-syria-moallem.html

Cihan News Agency. (2015, December 9). Cihan News Agency. Retrieved December 10, 2015, from Undersea Iran-Oman-India pipeline beneficial to all participants: http://en.cihan.com.tr/en/undersea-iran-oman-india-pipeline-beneficial-to-all-participants-1962450.htm

Dokoupil, M. (2012, May 24). Succession question fuels uncertainty in Oman. Retrieved December 3, 2015, from Reuters: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-oman-succession-idUSBRE84N0K420120524#4M14H9OBCft6idZj.97

Esfandiari, G. (2015, August 6). Senior Iranian official reveals details about secret talks With U.S. Retrieved December 4, 2015, from Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty: http://www.rferl.org/content/iran-secret-talks-salehi-nuclear-united-states/27174643.html

Grappo, G. A. (2015, June 3). In the shadow of Qaboos: contemplating leadership change in Oman. Retrieved November 20, 2015, from Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington: http://www.agsiw.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Grappo_Oman.pdf

Gupta, S. (2015, July 23). Oman: The unsung hero of the Iranian Nuclear Deal. Retrieved December 1, 2015, from Foreign Policy Journal: http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2015/07/23/oman-the-unsung-hero-of-the-iranian-nuclear-deal/

Jones, J., & Ridout, N. (2012). Oman, culture and diplomacy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Katzman, K. (2015, August 6). Oman: Reform, security and U.S. policy. Retrieved November 29, 2015, from Congressional Research Service : https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=787176

Ma, A. (2014, June 14). The Omani Backdoor: Europe’s decline and the growing importance of regional ties. Retrieved December 2, 2015, from Harvard International Review: http://hir.harvard.edu/the-omani-backdoor/

Nikou, S. N. (2015). Timeline of Iran’s Foreign Relations. Retrieved December 2, 2015, from United States Institue of Peace: http://iranprimer.usip.org/resource/timeline-irans-foreign-relations

Oman’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2015). Foreign Policy. Retrieved December 1, 2015, from Sultanate of Oman Ministry of Foreign Affairs: https://www.mofa.gov.om/?p=796&lang=en

Phillips, A. (2015, July 31). Why the Iran deal is so huge for Obama’s legacy. Retrieved December 8, 2015, from The Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2015/07/31/why-the-iran-deal-is-huge-for-obamas-legacy/

Pourmohammadi, E. (2015, July 15). Oman is Iran’s trade priority, says ambassador. Retrieved December 2, 2015, from Times of Oman: http://www.timesofoman.com/article/63851/Business/Economy/Oman-is-Iran’s-trade-priority-says-ambassador

Rosenberg , M., & Fahim, K. (2015, September 20). 2 Americans among 6 hostages freed in Yemen after months of captivity. Retrieved December 7, 2015, from New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/21/international-home/2-american-hostages-freed-in-yemen-after-months-of-captivity.html?_r=0

Rozen, L. (2015, August 11). Inside the secret US-Iran diplomacy that sealed nuke deal. Retrieved November 28, 2015, from Al-Moniter: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/08/iran-us-nuclear-khamenei-salehi-jcpoa-diplomacy.html

Sanger, D. E. (2015, May 13). Saudi Arabia Promises to Match Iran in Nuclear Capability. Retrieved December 1, 2015, from New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/14/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-promises-to-match-iran-in-nuclear-capability.html?_r=0

Savyon, A., Carmon, Y., & Mansharof, Y. (2015, September 16). Iranian officials reveal that secret negotiations with U.S. began In 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2015, from The Middle East Media Research Institute: http://www.memri.org/report/en/0/0/0/0/0/0/8752.htm#_edn2

Shah, A. (2015, August). Where does Oman and Iran’s pipeline leave Saudi Arabia? Retrieved December 2, 2015, from Gulf State Analytics: https://gallery.mailchimp.com/02451f1ec2ddbb874bf5daee0/files/GSA_Report_August_2015_.pdf

U.S. Department of Energy. (2012, January 4). The Strait of Hormuz is the world’s most important oil transit chokepoint. Retrieved December 5, 2015, from U.S. Department of Energy: http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=4430

Valeri, M. (2014, March). Oman’s mediatory efforts in regional crises. Retrieved November 28, 2015, from The Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre : http://www.peacebuilding.no/var/ezflow_site/storage/original/application/c3f2474284d7aaeadeb5a8429ef64375.pdf

World Bank. (2015). Military expenditure (% of GDP): Oman. Retrieved December 8, 2015, from World Bank: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS/countries/OM?display=graph

Written by: Sumaya Almajdoub

Written at: George Washington University

Written for: Ambassador Edward Gnehm

Date written: December 2015

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Puzzle of U.S. Foreign Policy Revision Regarding Iran’s Nuclear Program

- Laboring for Nuclear Disarmament? The Diplomacy of the Hawke-Keating Governments

- Deterrence and Ambiguity: Motivations behind Israel’s Nuclear Strategy

- Indian Perspective on Iran-China 25-year Agreement

- The Long March to Peace: The Evolution from “Old Diplomacy” to “New Diplomacy”

- Poliheuristic Analysis: 2008 Indo-US Civil Nuclear Agreement