Introduction

Nonviolent action has existed as a technique for achieving social and political objectives from as early as Roman Times, however it was not until Gandhi’s Satyagraha campaigns in South Africa (1906-1914) and India (1919-1948) that nonviolent action was considered a conscious method of collective political action (King 2007:13). At a most basic level, as the name implies, nonviolent action is an active pursuit of a desired outcome, social or political, outside the formal institutions or procedures of the state, that does not involve the use or threat of violence or armed force (Schock 2003:705). Yet beyond this basic definition, there is, what John E. Smith (1969) calls, an ‘inescapable ambiguity of nonviolence’. On the one hand, nonviolence is an expression of a moral principle, that the ‘right’ way to treat human beings, in all circumstances, is with compassion. On the other hand, nonviolence is also intended to be a powerful means of achieving a desired outcome. In other words, the ambiguity comes from what is perceived to be a mutually exclusive relationship between morality and power in nonviolent action. Most scholars of nonviolent theory reinforce this idea by choosing to emphasise morality or power in their work, but rarely both. Those who emphasise the morality of nonviolence are known as principled proponents, whilst those who emphasise its power are known as pragmatic proponents. It therefore appears that the advocate of nonviolent action is torn between the conviction that it is either moral or powerful.

However this essay suggests that this need not be the case, that nonviolent action can, at the same time, be pragmatic in its power to achieve the desired goal and also be principled by being rooted initially in morality. Therefore, it is proposed that the relationship between morality and power in nonviolent action is not one of mutual exclusivity but one of mutual inclusivity. The main reason for this is that morality needs power: principled proponents of nonviolence also need to be pragmatic and, there is empirical evidence which supports this assertion. To a lesser extent, it may also be the case that pragmatic proponents of nonviolence are guided to it as a method by some underlying moral consideration. The implication of this argument is twofold: firstly, it offers a new understanding of nonviolence, which incorporates both principled and pragmatic aspects and secondly, in doing so, it makes the nonviolence position a stronger one.

This essay will begin by looking at the well-known work of Mahatma Gandhi and Gene Sharp. This work and the conclusions of other scholars, tend not to support the argument of this essay, as morality and power are often pitted against each other, with no consideration given to their potential compatibility. However, the subsequent section will show that less known writings of Gandhi and, although to a much lesser extent, Sharp, allow them to be repositioned in the nonviolent spectrum. By exploring this part of their work and some case studies, the argument that morality and power can be mutually inclusive in nonviolent action does find significant support. The essay will then conclude by summarising the key points, all of which support the proposed understanding of nonviolent action as both moral and powerful.

Gandhi vs. Sharp

Gandhi is a principled proponent of nonviolence, first and foremost, because of the central importance he places on morality. Underpinning Gandhi’s commitment to nonviolence is a profound moral principle known is ahisma, which means non-harm or non-injury to all living things in thought, word and deed (Atack 2012:13). However for Gandhi, this moral commitment does not merely entail a negative state of harmlessness but it is also a positive state of actively doing good. Therefore, taking the moral idea of ahisma and translating it into political practice, Gandhi coined the term ‘Satyagraha’ to refer to his nonviolent action. Satyagraha is considered the ultimate example of principled nonviolence given its foundations in the Hindu religion and its subsequent moral impetus, derived from its connection to ‘Truth’. Comprised of the word Satya, meaning truth, and Agraha, meaning firmness, Satyagraha translates to ‘clinging to truth’ and so implies working steadily towards a discovery of the truth. The moral weapon of Satyagraha in this discovery is nonviolence and the reason for this is that ‘no one has the right to coerce others to act according to his own view of truth’ (Harijan 24 November 1933). No one has the right to coerce others because no one is capable of knowing the absolute truth and therefore error is always a possibility. Consequently in conflict, humans are not justified in using violence to deal with opponents because no side of any conflict can be sure of their own moral position. To use violence to punish or inflict suffering on others, is therefore unjustifiably forcing others to accept the negative consequences of our moral mistakes (Atack 2012:9).

Guided by Gandhi, contemporary principled proponents of nonviolent action therefore adopt it because they believe it to be intrinsically valuable and inherently immoral. All physical violence is rejected because it causes unnecessary suffering and dehumanises and brutalises the victim and executioner (Dudouet 2011:13). Furthermore, during a conflict principled proponents view the opponent as a potential partner in the struggle, and are concerned with re-establishing communication with them in order to convince them of the error of their ways, through conversion not coercion (Weber 2003:258). In short, for Gandhi, and his contemporary devotees, moral conviction is the basis of, and vital to the success of, nonviolent action. Perhaps surprisingly, there was a point in Gene Sharp’s early career that he could have been considered a principled Gandhian devotee. In his youth, Sharp immersed himself in Gandhian studies and his work was characterised by principled idealism. However the events of the India/China border war got Sharp thinking, and he came to the conclusion that sometimes Gandhian nonviolence, based on moral principles, would not only not always be enough, but could also be a hindrance rather than an asset in terms of achieving desired outcomes (Weber 2003:257).

Sharp’s work therefore started to focus on developing a pragmatic approach to nonviolence that was both realistic and powerful, and his first step in doing so was to abandon Gandhi’s emphasis on morality. The point was not to imply that being a moral nonviolent activist was wrong per se, but that in order to make nonviolent action most effective it needs to operate in a context that ‘enables the rest of the population to adopt [it] without commitment’ (Sharp 1984:11). Therefore, rather than advocating nonviolence on a moral basis and consequently ‘ignoring social reality’ (Sharp 1980:395), Sharp moved to champion nonviolence on a practical level, based on its power to achieve desired social and political objectives. The key feature of Sharp’s pragmatic nonviolent action then is power, not morality and it is considered not a way of life but an active response to the problem of how to wield power effectively and achieve desired social and political objectives. As a result of this position, that pragmatic nonviolence is ‘what people do, not what they believe’ (Sharp 1973:110), Sharp focused his attention to 198 different methods of pragmatic nonviolent action, including the likes of public speeches, leaflets, protests, singing and marches (http://www.aeinstein.org/). These methods omit any mention of, or reliance on, Gandhian principles and instead they are solely based on actions that have proven effective in past conflicts.

This Sharpian theory is considered the foundation of contemporary pragmatic nonviolent action. Pragmatic proponents, guided by Sharp, use nonviolent action because they believe it to be the most powerful method available in the given circumstances. Contrary to Gandhian proponents, Sharpian proponents view conflict as a relationship between antagonists with incompatible interests and their goal is to coerce concessions from them (Weber and Burrowes 1991: no pagination). A clear example of pragmatic rather than principled nonviolent action is the Franklin River Campaign in Australia. Nonviolent action, notably the blockade of the River Gordon, was chosen as a method for coercing concessions from the government, after realising that lobbying was not powerful enough to put pressure on the federal parliamentary parties in the run-up to the federal elections in 1983 (Weber and Burrowes 1991: no pagination). The activists involved in this campaign were pragmatic and were concerned with realising their own power to alter relationships, rather than concerns about the arrival at ‘truth’.

What is clear from the discussion above, is that even a brief overview of the Gandhian and Sharpian theories of nonviolent action exposes why Gandhi, the pioneer of principled nonviolence, and Sharp, the pragmatic Clausewitz of nonviolence, are typically viewed as opposites. One emphasises morality and the other emphasises power. In terms of what this means regarding the relationship between morality and power, it does not seem unreasonable to infer that given Gandhi’s dismissal of power and Sharp’s dismissal of morality, both believed the other to be incompatible with the one that they were centrally concerned with. Arguably some other scholars have drawn similar conclusions to this, given their instance that principled and pragmatic nonviolent action are incompatible.

Conclusions of Other Scholars

For Judith Stiehm (1968) principled and pragmatic nonviolent action are incompatible because their motivations, morality and power, are incompatible. Stiehm reiterates the key distinction between Gandhian and Sharpian nonviolence, pointing out that principled nonviolence is motivated by a moral rejection of violence and coercion, whereas pragmatic nonviolence is motivated by the belief that it is the most powerful way of achieving certain means. Eddy (2012:188) turns his attention to assumptions, pointing out that principled and pragmatic nonviolence decisively part on the issue of means and ends. When searching for resistance tactics, the only concern for proponents of pragmatic nonviolence is that the means are powerful enough to lead to the attainment of the movement’s valued political ends, such as democracy and human rights. Therefore the assumption is that means and ends are separate. However for principled proponents, there is an intimate connection between means and ends, similar to the connection between the seed and the tree (Gandhi 1961:10). The concern is that the means are moral, not powerful, because the moral quality of the means creates and shapes the moral outcomes of the political action, and for this reason, nonviolence is intrinsically valuable. Eddy (2012:188) continues by looking at the practical implications of these differences between the two approaches, arguing that principled proponents lack the strategic power necessary to run a successful movement, whilst pragmatic proponents are charged with being ‘incapable of putting the ‘real’ power and virtues of nonviolence into practice’ because they do not buy into the morality of it.

To summarise, Gandhian and Sharpian theories of nonviolent action are considered by some scholars to be at opposite ends of the nonviolence spectrum, and the common thread amongst their reasoning is that one is concerned with morality, and one with power. This in turn affects their motivations, assumptions and practical implications. Whilst on a theoretical and philosophical level, these conclusions are undeniable, in some theoretical instances, and even more so empirically, it is reasonable to ask, are morality and power really at odds? In the case of principled nonviolence, arguably they are not because principled proponents are also pragmatic. This reversal is less true of pragmatic proponents but even still, there is some possibility that they too are guided by a, albeit subtle, moral commitment. So despite the dissimilarities between Gandhian and Sharpian theories of nonviolence and the subsequent tensions between morality and power, arguably they do not entirely exclude each other (Fisher et al, 2000; Satha-Anand, 2002; Martin, 2009; Dudouet, 2011).

Smith (1969) takes this conclusion further by claiming that it is not simply that power and morality do not exclude each other, but that they, in actual fact, cannot afford to exclude each other. Arguably an appeal to morality is always necessary if human action is not to be brutalised, however, and this is where morality and power merge together, it must also be recognised that conflicts cannot be resolved merely by appeal to morality alone, some instrument of power is required (Smith 1969:158). Smith writes ‘in a perfected kingdom of ends one might expect that all members would be motivated by reason alone, but the obvious and bitter fact is that we do not live in such a kingdom’ (1969:158). This supports the main argument of this essay, that the relationship between morality and power in nonviolent action is not necessarily one of incompatibility and that there is a need for them to instead be mutually inclusive. If proponents of nonviolent action recognise this need and in turn embrace the ‘double-barrelled’ (Smith 1969:158) character of their chosen method, the nonviolence position will only be stronger.

Principled Pragmatism

It has been acknowledged that Gandhi, a principled proponent of nonviolence, did embrace the ‘double-barrelled’ character of nonviolent action. Ironically, Sharp is one of the most prominent scholars to have acknowledged this, noting in his work Gandhi as a Political Strategist (1979) Gandhi’s seminal role in bringing together the two traditions of principled and pragmatic nonviolence. The title of this book presents Gandhi as something other than a principled proponent of nonviolence who is predominantly concerned with morality, and the content of the book itself justifies such a title. Sharp examines Gandhi’s own writings in Nonviolence is Peace and War and concludes that Gandhi’s main contribution was to offer people a powerful technique that they could use to effectively challenge their social and political problems. Sharp quotes Gandhi describing India taking up non-cooperation and how it must serve the purpose of delivering her ‘from the crushing weight of British injustice’ (Gandhi, quoted in Sharp 1979:276). This interpretation of Gandhi’s work, not considered above, leads to the valid observation that although Gandhi’s moral motives for using nonviolence were preponderant, Gandhi was also advocating nonviolent action as a powerful method to obtain social and political change.

It is not just other nonviolent theorists that recognise this, for Gandhi himself also admits to it in his own writings and displays it in his chosen methods of nonviolent action. Gandhi referred to ‘nonviolence as policy’ when acknowledging the power dimension of nonviolent action, which did ‘not at all need [moral] believers’ (Gandhi, quoted in Sharp 1979:279). What nonviolence as policy did need however, was a great deal of planning, preparation and execution based on close study. Numerous methods employed by Gandhi fit this description of nonviolence as policy, in other words, pragmatic nonviolence. Firstly, Gandhi’s use of self-sacrifice and public suffering was arguably intended to act as a powerful emotional tool, as he believed that self-sacrifice and public suffering of Satyagraha would effectively ‘touch those who employ violence and eventually convert them’ (Terchek 1998:210). Secondly, Gandhi’s fasts were also arguably a power tactic in the sense that he was aware that if he died as a result of the fasts, extensive violence would ensue across India. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that Gandhi was open about the fact that many, if not most, of his colleagues in the Indian National Congress and the majority of Indian participants of Satyagraha, pursued nonviolence for principled as well as pragmatic reasons.

Therefore, despite the obvious concern for morality which underpinned Gandhi’s nonviolent action, one cannot escape the fact that at times, Gandhi, and his Satyagrahi, were also concerned with the power of their nonviolent actions, in terms of how effective they would be in achieving their political and social objectives. Gandhi’s nonviolence, both in terms of his theoretical writings, as pointed out by Sharp, and his execution of Satyagraha in social and political reality, is neither one-dimensional or exclusivist. Thus the case of Gandhi, contrary to the conclusions in the first half of this essay, supports the argument that concerns of morality and power can in fact be mutually inclusive, both in theory and practice.

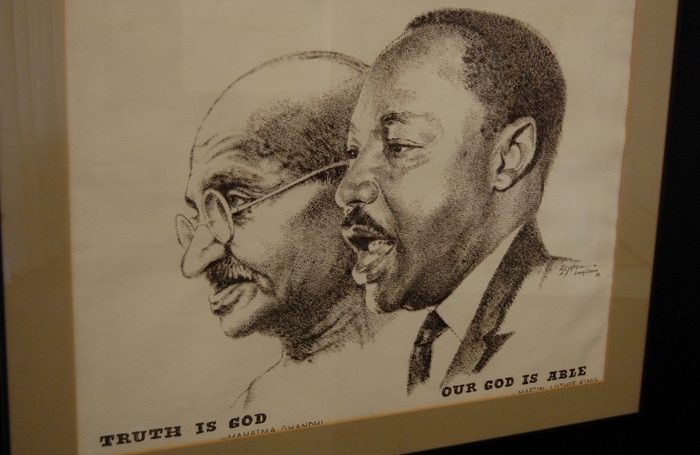

The argument also finds support in the case of Martin Luther King who, like Gandhi, is considered a pioneer of principled nonviolent action but who was also pragmatic, within a morally dictated boundary. Martin Luther King’s six principles of nonviolent action, articulated in his work Stride for Freedom (1958), by definition position him in the moral category of nonviolent action, some of which include nonviolence as a ‘way of life for courageous people’, which ‘seeks to win friendship and understanding’ and ‘chooses to love instead of hate’. However, further examination of Martin Luther King’s method of nonviolent action justifies repositioning him in the morality/power continuum. Referred to by James Colaiaco (1993:1) as one of ‘the greatest political strategists of all time’, Martin Luther King and his followers can be said to have often purposely created the circumstances that would ensure that their nonviolent action was most powerful and effective. For example, they often intentionally provoked racist attacks by the police, which would in turn attract media attention and increase support for their cause by mobilising complacent groups and the public, which would eventually compel the local authorities to enter into negotiations. With such a pre-planned and pragmatic strategy, Martin Luther King ‘appeared to be the lamb, [while] his nonviolent action embodied much of the power of the lion and the cleverness of the fox’ (Colaiaco 1993:143). Again like Gandhi, the case of Martin Luther King reveals that nonviolent action premised on morality, is typically not neglectful of pragmatic concerns of power and effectiveness.

The third and final case study is also a clear example of nonviolent action as both principled and pragmatic, concerned with both morality and power. Mubarak Awad played a pivotal role in organising nonviolent action during the First Palestinian Intifada, so much so that he is sometimes referred to as the ‘Gandhi of Palestine’. Awad’s nonviolent action consisted of two main strategies, the first was based on morality and the second on power. Inspired by his Christian Mennonite faith, Awad’s first strategy was to spread the message of Gandhi’s principled nonviolence to Palestinians: he encouraged Palestinians to see nonviolence as the only option, explaining to them the divinity of humanity and how conflict was a dialogue rather than ‘us’ versus ‘them’ which involved conversion of the opponent using moral influence (Ingram 2003:44-45). Awad’s second nonviolent strategy was to inform Palestinians about the tactics of Sharp, which he did through publishing an article called Nonviolent Resistance: A Strategy for the Occupied Territories (1984). In this article Awad explains why nonviolence is the most powerful strategy for resisting occupation and achieving political gain and he describes in detail which of Sharp’s 198 methods of nonviolent action he considers to be most effective in the Palestinian circumstances.

The reason why Awad promoted nonviolent action that was both principled and pragmatic, was because he realised the limitations of morality and consequently the need for power. Talking about the relationship between Palestinians and Israelis in 2003, Awad noted the level of hatred, sadness and killing that remained between them (Ingram 2003:56), making it impractical to promote the use of nonviolent action based on morality and ideas of forgiveness, love and compassion alone. Therefore, being a prime example of the main argument of this essay in practice, Awad realised that morality in nonviolent action needed power and in doing so, Awad not only acknowledged the existence of pragmatic nonviolence but he also made it part of his platform, adopting Sharpian rhetoric and combining it with his Gandhian morals. Perhaps then Awad’s label as the ‘Gandhi of Palestine’ needs some adjustment.

Therefore, from the three case studies explored above, it is possible that morality and power can be simultaneous considerations in nonviolent action, particularly in instances where principled nonviolence also needs to be pragmatic. It may not be the case that the nonviolent action as a result is equally as pragmatic as it is principled, but this is beside the point. In the three case studies above, nonviolent action was primarily an appeal to moral principle, but it was also seen as a powerful method to get things done. It is perhaps this desire to get things done, to achieve certain political and social objectives, that most simply supports the argument that morality and power are not at odds, because the two types of nonviolent action that claim them to be most important, principled and pragmatic, in the end both have the same goal of achieving social and political change. What is more, as the three cases studies have shown, is that nonviolent action will only be stronger when morality and power are considered together, rather than apart.

Pragmatic Nonviolent Action: Room for Principles?

To some extent, arguably Sharp was sympathetic to this idea, that morality and power could not only be mutually inclusive in nonviolent action, but that this would actually make nonviolent action more effective. In a lecture delivered at Notre Dame University, Sharp explained that ‘believers’ and ‘nonbelievers’ (principled and pragmatic proponents) of nonviolent action can cooperate and thus with the development of wise strategies and skilled applications of nonviolent action, the tension between being politically powerful and morally faithful can be resolved (Sharp 2006, lecture at Notre Dame University). What is clear from this lecture is that Sharp places the burden on the ‘believers’ to make use of the ‘skills’ of the ‘nonbelievers’, which does support the argument of this essay that morality needs power. However, does it also imply that Sharp does not see it possible or necessary for pragmatic proponents to take a leaf from the book of the principled proponent? Arguably there is a section of Sharp’s work which, admittedly with some reading inbetween the lines, could support the argument that pragmatic proponents are in some way initially covertly guided to nonviolent action by moral principles, and that throughout the nonviolent process, a degree of adherence to some moral principles would make their nonviolent action more powerful.

In The Dynamics of Nonviolent Action (1973), Sharp discusses three issues which have significant moral undertones that he considers to be relevant to the pragmatic proponent of nonviolent action. The first issue Sharp addresses is the problem of mixing violent and nonviolent action, where Sharp warns pragmatic proponents of nonviolence against resorting to acts of violence because once this would occur, the original nonviolent movement, would lose sympathy and legitimacy. This implies that nonviolent action should always be the chosen method, even in instances where it is not the most powerful or effective. However if power and effectiveness are key concerns for Sharp, why dismiss a violent method that in a given situation would be more powerful and effective than a nonviolent method? Arguably, that Sharp dedicated time to listing 198 methods of nonviolent action, with zero violent alternatives, implies that as a starting point Sharp believes in nonviolent action because it is ‘right’. From this interpretation it could be argued that Sharp’s initial decision to commit to nonviolent action as a method for achieving social and political objectives, was a moral one, even if he himself does not admit it.

The second and third issues Sharp addresses are the necessity of self-discipline and refusal to hate. Admittedly not so much the necessity of self-discipline, but the refusal to hate is a quality that could easily be found in a principled Gandhian/Martin Luther King guide to nonviolence. Sharp’s point in emphasising these two principled issues, is that adherence to them, in terms of having enough self-discipline to persist with nonviolence in the face of repression and the ability to refrain from hating the opponent, makes the nonviolent action more effective. Thus Sharp’s writing in this instance does leave room for the conclusion that alongside his emphasis on power, there is also some recognition of the role that moral principles can play in pragmatic nonviolent action. This is not to suggest that pragmatic proponents of nonviolent action come to be as concerned with moral principles as much as principled proponents do with power. However, that morality even plays a subtle role in a power-centred pragmatic approach to nonviolence, is interesting when considering the relationship between morality and power in nonviolent action, particularly given how it is mostly perceived by scholars to be one of incompatibility.

Conclusion

The general field of nonviolent theory is typically divided between principled proponents who emphasise the fundamental importance of morality and pragmatic proponents who emphasise the fundamental importance of power, and as such these elements are often pitted against each other as being mutually exclusive elements of nonviolent action. However it has been argued that this distinction is not as solid as the literature implies. This essay has shown that in both theory and practice, principled proponents of nonviolence can and have been pragmatic out of necessity; Gandhi, Martin Luther King and Mubarak Awad were all centrally concerned with morality, but they were also pragmatic in their nonviolent action, given their concern with the power of their actions to achieve their desired goals. Although principled, they also want to be effective. The pragmatists, with their emphasis on power, also want to be effective, and it was suggested in this essay that Sharp, although covertly, implies in his writing that adherence to some moral principles will enhance the effectiveness of the nonviolent action. Therefore it is valid to conclude that the relationship between morality and power in nonviolent action can be one of mutual inclusivity, rather than mutual exclusivity.

It is of course important to consider context when reflecting on this finding; the extent to which the relationship between morality and power is one of mutual inclusivity depends on a variety of factors such as society, leadership and each individual claiming to be part of the movement. However the issue of extent aside, we can be sure that the distinction drawn between principled proponents and morality and pragmatic proponents and power is not as solid as often portrayed. The implication of this, that the relationship between morality and power in nonviolent action is one of mutual inclusivity, is that a new understanding of nonviolent action is needed. The finding implies a broader understanding of nonviolence, which is not defined nor confined to the principled/pragmatic continuum. This essay therefore suggests a new understanding of nonviolence as one which incorporates issues of both morality and power. Nonviolent action can therefore be understood as powerful in its capacity to achieve social and political change, but also moral by respecting the worth of each human being by refraining from causing harm to opponents.

References

‘198 Methods of Nonviolent Action’ (http://www.aeinstein.org/nonviolentaction/198-methods-of-nonviolent-action/) The Albert Einstein’s official portal site, accessed on 20th January 2016

Atack, I. (2012). Nonviolence in Political Theory. Edinburgh University Press: UK

Colaiaco, J.A. (1993), Martin Luther King Jr: Apostle of Militant Nonviolence, New York: St Martin’s Press

Dudouet, V, ‘Nonviolent Resistance in Power Asymmetries’, in B. Austin, M. Fischer, H.J. Giessmann (eds.) 2011, Advancing Conflict Transformation, The Berghof Handbook II, Opladen/Framington Hills: Barbara Budrich Publishers, available online at www.berghof-handbook.net, accessed 14th January 2016

Eddy, M.P. (2012), ‘When Your Gandhi Is Not My Gandhi: Memory Templates and Limited Violence in the Palestinian Human Rights Movement’ in Nonviolent Conflict and Civil Resistance: Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change, 34, pp185-211

Fisher, S, et al. (2000). Working with Conflict: Skills and Strategies for Action. London: Zed Books.

Gandhi, Harijan, 24 November 1933, in Collected Works, 56:216

Gandhi, M. K., 1961: Non-Violent Resistance (Satyagraha), New York, Schocken.

Ingram, C. (2003), ‘Murbarak Awad’ in The Footsteps of Gandhi: Conversations with Spiritual Social Activists, Berkeley, CA: Parallax, pp37-57

King. M.E. (2007), A Quiet Revolution. The First Palestinian Intifada and Nonviolent Resistance, New York: Nation Books

King, M.L. (1958), Stride toward freedom: the Montgomery story, New York: Harper

Martin, B. (2009), ‘Dilemmas in promoting nonviolence’, Gandhi Marg, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp429-453

Mubarak, A. (1984), ‘Nonviolent Resistance: A Strategy for Occupied Territories’ in Journal of Palestinian Studies, 13, no 4, pp22-36

Satha-Anand, C. (2002), ‘Overcoming the Illusory Divide twixt Nonviolence as Pragmatic Strategy and as Lifestyle’, available at http://www.understandingeconomy.org/assets/PDF/Nonviolence_Pragmatic%20Strategy_Lifestyle.pdf, accessed 21st January 2016

Schock, K. (2003), ‘Nonviolent Action and Its Misconceptions: Insight for Social Scientists’ in Political Science and Politics, Vol. 36, No. 4 pp 705-712

Sharp, G. (1973), The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Porter Sargent Publishers

Sharp, G. and Sergeant, P. (1973), The Politics of Nonviolent Action: Part Three: The Dynamics of Nonviolent Action, Boston, pp 608-635

Sharp, G. (1979), Gandhi as a Political Strategist: with Essays about Ethics and Politics, Boston: Porter Sargent

Sharp, G. (1980), Social Power and Political Freedom, Boston: Porter Sargent

Sharp, G. (1984), ‘People Don’t Need to Believe Right’ in National Catholic Reporter, September 7

Sharp, G. (2006), ‘What are the Options in Acute Conflicts for Believers in Principled Nonviolence?’, lecture delivered on September 22 at Notre Dame University, available at http://www.reteccp.org/biblioteca/disponibili/novviolenza/sharp/BELIEVERS.pdf, accessed 20 January 2016

Smith, J.E. (1969), ‘The Inescapable Ambiguity of Nonviolence’, Philosophy East and West 19:2

Stiehm, J. (1968), ‘Nonviolence is Two’ in Sociological Inquiry, Vol 38, 1, pp23-30

Terchek, R. (1998), Gandhi: Struggling for Autonomy, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers

Weber, T. and Burrowes, R.J. (1991), Nonviolence: An Introduction, available at www.nonviolenceinternational.net, accessed 21st January 2016

Weber, T. (2003), ‘Nonviolence Is Who? Gene Sharp and Gandhi’, Peace & Change, 28.2. pp250-270

Written by: Sarah Wallace

Written at: Trinity College Dublin

Written for: Iain Atack

Date written: January 2016

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Analysing the ‘Special Relationship’ between the US and UK in a Transatlantic Context

- The Bio/Necropolitics of State (In)action in EU Refugee Policy: Analyzing Calais

- Morality, Media and Memes: Kony 2012 and Humanitarian Virality

- What Role did Christian Teachings Play in the American Civil Rights Movement?

- Is Decolonisation Always a Violent Phenomenon?

- Understanding Power in Counterinsurgency: A Case Study of the Soviet-Afghanistan War