On Thursday, April 6th 2017, President Trump authorised unilateral missile strikes against a Syrian air base. Since then, academics and analysts have grappled with the legality and morality of the actions taken. Regarding the former, some focus on domestic law, some on international law and some on both national and international. Regarding the latter, Tesón has uses Just War Theory to claim ‘Trump did the right thing’ see here (although the focus is somewhat limited in that very few Just War criteria are assessed). Alternatively, Aidan Hehir has argued the strikes were both illegal and immoral. The aim here is not to go over these debates, or to ignore the many other concerns involved (see here and here), but instead, to call for a greater focus on international legitimacy. As it stands, a dichotomy has emerged with a gridlocked UN Security Council on one side and a unilateralist ethic on the other. But, there is a third way: The Uniting for Peace Resolution has the potential to move the debate over Syria into the United Nations General Assembly. Although the outcome of any UN General Assembly debate would not be legally binding, it may still provide a legitimate platform on which to create a foreign policy agenda toward Syria.

At the outset, it is important to answer a question. What is international legitimacy and how does it differ from existing appeals to morality and international law? As I have argued elsewhere, the marginalisation of international law within Just War Theory tends to create a reductionist understanding of legitimacy that becomes synonymous with morality. At the same time, any focus on law itself, fails to understand the role that morality plays in shaping the law (H. L. A. Hart here). In contrast, and upholding Ian Clark’s study of international legitimacy, I subscribe to the view that international legitimacy should be understood in a hierarchical position above morality and legality. In itself, international legitimacy has no independent value but instead draws its value from morality, law, power, consensus, and constitutionality. Accordingly, any attempt to ground legitimacy on any one of these components is flawed because it fails to gauge the multidimensional process that underpins the construction of international legitimacy.

Against this backdrop, I want to focus on the future rather than the past and outline two key points. First, the US should not go it alone. Second, the legitimacy that President Trump needs does not lie in unilateralism, or the UN Security Council, but instead, in the Uniting for Peace Resolution. This is not to say that I expect the US will do this, but instead, to offer a normative argument that they should do.

Why America Should Not Go It Alone

It is important to recognize that at present, we simply do not know what President Trump has planned. Following the strikes, a US Defense Official is said to have told Reuters that it was a ‘one-off’ which implies there is no plan for escalation. That said, it is not clear that the US has a plan at all. On April 10th, The New York Times reported that the ‘Administration is in Disagreement with Itself’ over Syria. Moreover, whilst many ‘voices are heard on Syria, Trump is silent’. Meanwhile, reports suggest that Putin will now not even meet with US Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson.

So what do we know? First, Trump does not downplay his willingness to resort to unilateral action. Just says before the strike on Syria, Trump declared that he is prepared to go it alone to address the threat posed by North Korea. Chinese state newspapers have since claimed that the airstrikes in Syria were, at least in part, designed to intimidate North Korea. Second, the speed at which the US took the action further underlines a commitment to unilateralism. It is unclear as to whether the US administration contacted NATO allies prior to the strikes but either way, it appears that Trump made up his mind very quickly that the US could and would do this alone. This is despite the fact that according to the UN Special Envoy for Syria, Steffan Mistura, we ‘have not yet any official or reliable confirmation’ of who was responsible. Third, on April 10th, US Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis, stated that ‘the Syrian government would be ill-advised ever again to use chemical weapons’. Therefore, despite the lack of a clear strategy on Syria, the current silence from the Trump administration does nothing to hide a pre-existing commitment to unilateralism.

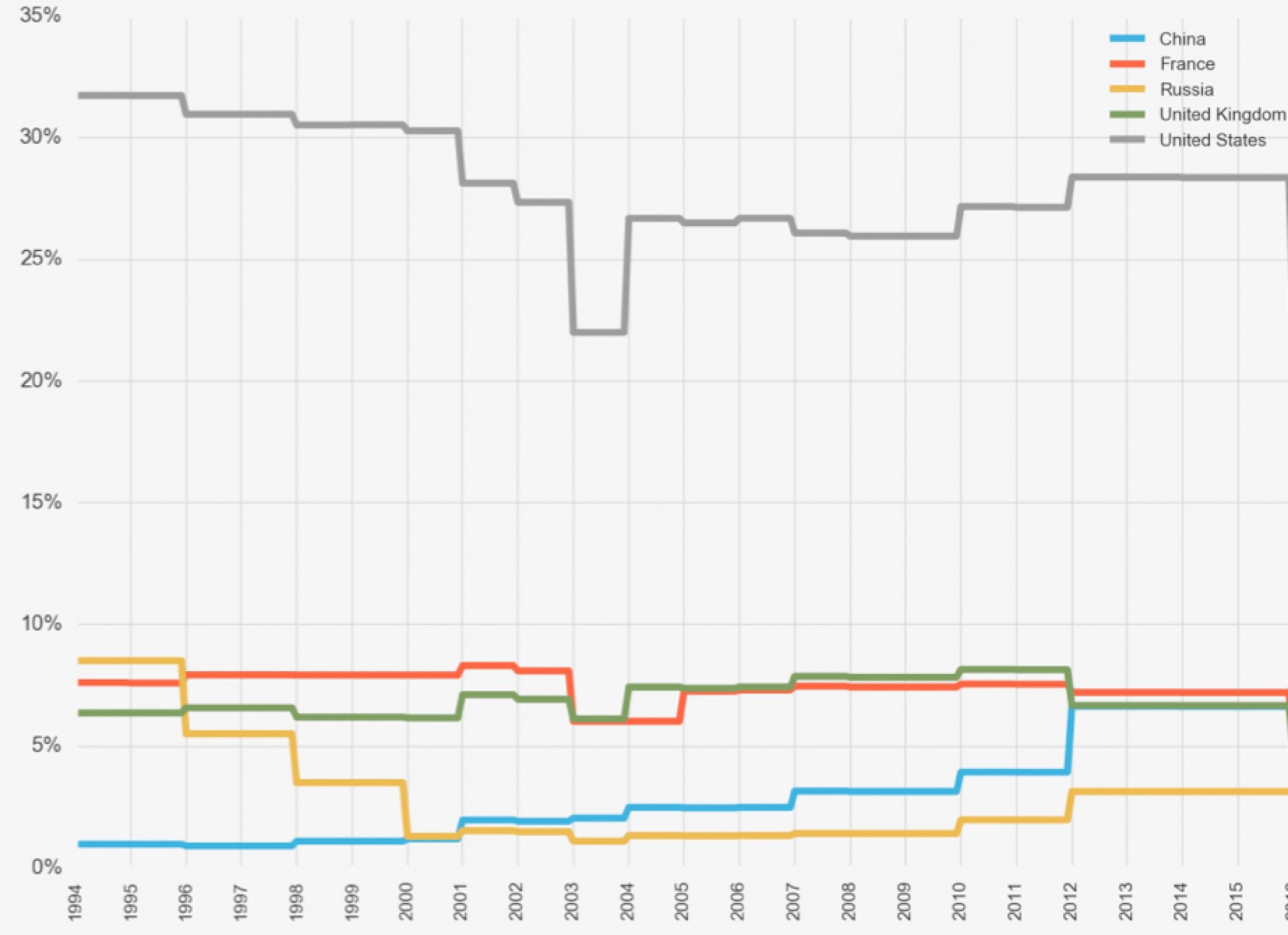

To some extent, this is understandable and is also coherent with Trump’s Campaign’s focus on the lack of match funding by either NATO allies or the permanent five member of the UN Security Council. The graph below was put together by Paul Williams and illustrates this point well. Putting aside debates over who should pay what, the raw data helps us understand Trump’s position. He feels the US carries too much of the financial burden when it comes to both the UN and NATO. With this in mind, why should the US not simply go it alone?

The Permanent Five Members Financial Contributions to UN Peacekeeping since 1994.

Trump needs to understand the value that multilateralism brings in terms of international legitimacy. This calls for a more informed understanding of international relations that simply reducing the United Nations and NATO down to dollar signs. I am sure such thinking served him well as he expanded his Trump empire, but it will not serve to aid US foreign policy. Any such approach is counter-productive as it fails to acknowledge the value of multilateralism. As Andrew Hurrell notes

states need multilateral security institutions both to share the material and political burdens of security management and to gain the authority and legitimacy that the possession of crude power can never on its own secure (Hurrell, p. 192 here).

In other words, power it itself is not enough. To return to Clark’s focus on morality, law, power, consensus, and constitutionality – it is imperative that the US does not fall into the trap of thinking ‘might is right’. When the US pursued such thinking in 2003 this created a broader crisis of legitimacy for the United States. On April 7th 2017, such issues were raised within the United Nations Security Council debate on Syria as representatives expressed concern that the powerful US was attacking the powerless Syria without following due process. To avoid a legitimacy crisis going forward, Trump must do more to align US power with international law, morality, consensus, and constitutionality. Yes, this is a complex, difficult, long term process but it will help the US gain the support it needs to address profoundly challenging issues such as Syria and North Korea.

The Uniting For Peace Resolution

To avoid a legitimacy crisis over Syria, the answer lies not in unilateralism, nor the UN Security Council, but in the United Nations General Assembly. As Dominik Zaum explains, the Uniting For Peace Resolution emerged in the 1950s as ‘the US and its allies’ sought ‘to change the institutional balance of power between the Security Council and the General Assembly at a time when the Council was deadlocked because of regular Soviet votes’ (see here p. 155). Its relevance is clear. If there is gridlock in the UN Security Council then the Uniting For Peace seeks to refer the issue at hand to the UN General Assembly which can then have a vote and make recommendation. To do this, the US needs a majority vote within the Security Council or the General Assembly. The purpose of the Uniting for Peace Resolution therefore, is to engage the power of the UN General Assembly in discussions over the Use of Force in international relations. This was built upon an assumption that although the United Nations Security Council has ‘primary responsibility’ it does not have ‘exclusive responsibility’ for maintaining international peace and security. In total, the Uniting for Peace Resolution has been used eleven times and has featured in contemporary debates over the Responsibility to Protect in 2001, UN Reform in 2004/05 and the Syrian crisis – see here. I would argue that following the recent chemical weapons attack there is a window of opportunity for the Uniting for Peace Resolution to be invoked.

So what would this mean for international legitimacy? There are some obvious strengths and one important limitation. Regarding the former, if, the US gained the necessary support in the UN General Assembly then this would substantially strengthen the United States position over Syria. To return to the multi-dimensional understanding of international legitimacy, if a consensus could be forged in the General Assembly, this would evidence that the US has broad moral and political support within the international community. For example, the Independent Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty addressed the issue of an intervention to stop mass violence against civilians that is authorised via the Uniting for Peace Resolution, it concluded that, ‘an intervention which took place with the backing of a two-thirds vote in the General Assembly would clearly have powerful moral and political support’ (see here, p. 48). Regarding the latter, a sticking point remains: legality. The United Nations General Assembly can only make recommendations and cannot therefore provide the US with the international legal mandate to pursue its proposed policy. That said, to return to Clark’s understanding of international legitimacy, if the US does gain the necessary political, moral, powerful, and consensual support then its action could be deemed legitimate – even without explicit legal grounding. For example, recall that the military intervention in Kosovo was deemed to be as ‘illegal but legitimate’. In other words, in certain exceptional cases international moral consensus can overcome the legitimacy deficit.

Overall, with the chemical weapon attack creating a window of opportunity for action, I feel now is the time to pursue options under the Uniting for Peace Resolution. Invoking the words set forth in 1950, it seems that the international community is conscious of the ‘failure of the UN Security Council to discharge its responsibilities on behalf of all member states’. Moreover, it ‘recognizes that such failure does not deprive the General Assembly of its rights or relieve it of its responsibilities under the Charter in regard to the maintenance of international peace and security’ see here.

On a final note, let me stress, I do not know whether two-thirds of the UN General Assembly will vote in favor of US-led unilateralism, nor am I saying they should do. But with a unilateral thirst on one hand, and a paralyzed UN Security Council on the other, I think the best platform for understanding what constitutes a legitimate response to Assad lies in the United Nations General Assembly.

*This article stems from a discussion with Professor Jason Ralph at the University of Leeds and follows on from previous collaborative work on this topic.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – China and the Rebuilding of Syria

- Trump’s Trade War: US Geoeconomics from Multi- to Unilateralism

- Opinion – Syrian Comedy post-Assad

- Opinion – Re-election in Doubt: The Perfect Storm Approaches Donald Trump

- Scorekeeping With Donald Trump in a COVID-19 Language Game

- Age of the Deal: Donald Trump Won the Battle of Seattle