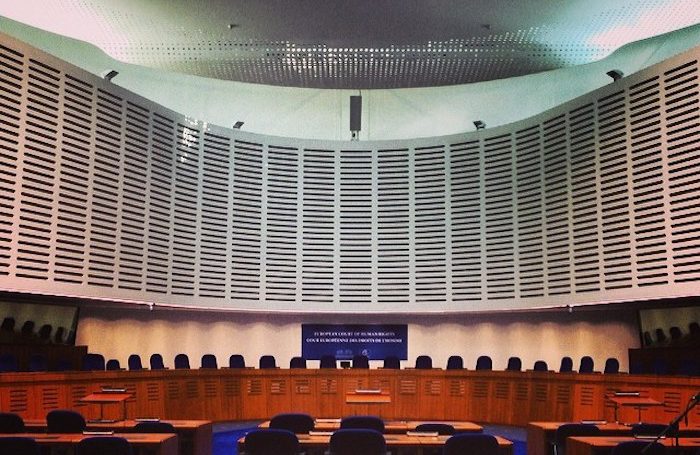

On the face of it, Brexit has no implications whatever for the UK’s relationship with the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), or for either of these institutions themselves. Formally, by leaving the EU, the UK would merely join the existing 19 non-EU states which belong to the 47-member Council of Europe, the parent body of the ECHR and the ECtHR. However, many Brexiteers are also hostile to the ECtHR, others fail to realise that departing the EU will leave the UK’s ECHR commitments intact, and hostility towards the Strasbourg institutions is not limited to those who want to leave the EU. For example, as Home Secretary before the referendum vote, Teresa May, a Remainer, advocated UK withdrawal from the ECHR (call it ‘ECxit’), in spite of the fact that belonging to the Council of Europe is effectively a condition of EU membership. However, she later announced that she had changed her mind because ECxit lacked sufficient Parliamentary support.

The chances of the UK leaving the Strasbourg system will, therefore, depend upon whether Brexit decreases or increases Euro-scepticism in British politics over the next few years. As things stand, this prospect seems to have diminished in the wake of the June 2016 vote. However, even if ECxit should occur, ECHR rights are likely to remain a feature of British law because even the Conservative party, which envisages a reconfiguration of the national human rights landscape, is committed to their reproduction, subject to reduced national judicial enforcement, in a British Bill of Rights intended to replace the Human Rights Act which domesticated the ECHR at the beginning of the 21st century.

Brexit will also not affect those UK laws which derive from the ECHR rather than from the EU, the latter of which are more developed in certain areas including, for example, employment, migration, equality, children, data protection and the environment. But the distinction is not straightforward. For one thing, the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights duplicates provisions found in the ECHR, sometimes in identical, sometimes in truncated, and sometimes in expanded form. Technically, the case law of the European Court of Justice (ECJ), the EU’s principal judicial institution, will no longer bind the UK once Brexit takes effect. However, while the ECJ’s human rights jurisprudence has been influenced by the ECtHR’s, the same is not true the other way around, not least because the former has only begun to take an interest in human rights comparatively recently.

As long as it remains a member of the EU – that is, for the two years or more it is expected to take for the divorce, triggered in March 2017, to be finalized – the UK will also remain formally subject to those EU human rights laws which have no Strasbourg parallel. However, it is unlikely that, in this period, any new EU legislation or fresh rulings of the ECJ would or could be enforced against the UK’s will. Thereafter, the status of distinctively EU human rights law will be difficult to ascertain. For one thing, it may depend upon whether or not, post-Brexit, the UK remains a member of the single market in common with non-EU states, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. If it does, it will continue to be subject to some EU rules with a human rights dimension, in all probability including those concerning free movement of people, a cluster of rights less well protected in the Strasbourg system. And even if the UK severs all connection with the EU, except for a tailor-made trade deal, the EU is likely to insist on the inclusion of human rights obligations as it does in its trading relations with all non-EU states.

It is not clear whether adherence to ECHR rights would suffice. However, whatever happens, once the UK’s membership of the EU finally terminates, the UK will no longer have to comply with human rights obligations enshrined in EU treaties. In the short term the proposed Great Repeal Bill will retain existing EU law including in the human rights field. But, once the divorce is finalized, it is not clear which, if any, exclusively EU human rights norms will then be earmarked for extinction.

Brexit has no formal or immediate implications for the Council of Europe either. But there may, nevertheless, be some subtly negative consequences. The UK is one of the oldest democracies in the world, together with France and the US is the birthplace of the human rights ideal, and, by contrast with the EU, is a founding member of the Council of Europe. The legitimacy and authority of the Strasbourg institutions are also under strain in some other member states, although not to the same extent as in the UK. The credibility of the transnational judicial protection of human rights could, therefore, be significantly damaged both internally and wider afield should the vote to leave the EU eventually sweep the UK out of the Strasbourg system too.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Brexit and the 2019 European Elections

- Grexit and Brexit: Lessons for the European Union

- The Days of May (Again): What Happens to Brexit Now?

- Post-Brexit EU Defence Policy: Is Germany Leading towards a European Army?

- Brexit Britain in the Transatlantic Standoff: Bridging the Gap?

- An ‘Expert’ Perspective on Brexit… Means Brexit