Since December 2017, Iran has seen more anti-governments protests, strikes, sit-ins and uprisings than any other country in the world. By all indicators, Iran is undergoing a revolution, and now the debate is shifting from whether the theocratic regime will fall to what, if any, alternative comes next? One Iranian opposition group, the Muajahedin-e-Khalq (MEK), has taken center stage in this debate, both on the part of its detractors and backers in the Iranian political landscape. Given their enduring history, international standing, network of deep assets inside the regime’s national security structure, organizational and political capacity to influence Iran’s political scene at home and policy formulations abroad, a brief assessment of the MEK is necessary for better evaluating the “What next” conversation.

Who Are the MEK and What Do They Stand For?

The MEK organization was established more than half a century ago, and is, by all accounts, the oldest political organization in contemporary Iranian history, having survived both the dictatorial reign of Iran’s Shah and, now, the theocracy.

Irrespective of one’s view of the group, no one can provide a complete account of Iran’s contemporary political history without reference to the MEK. It is the only group with proven experience in managing an all-volunteer organization as its support network spans across multiple continents. It is the only organization in the Middle East that holds over three decades worth of historic experience in addressing and practicing the notion of full equality between men and women among its rank and file. Notably, it is the only political movement in the world, in which two-thirds of its members are men yet remains under the directorship of an all-female elected council.

The organization has successfully mobilized various international campaigns to fight the terror designation and won all its court cases in the US and Europe by 2012 (Varasteh, 2015).

What Next? The Kazerun Case.

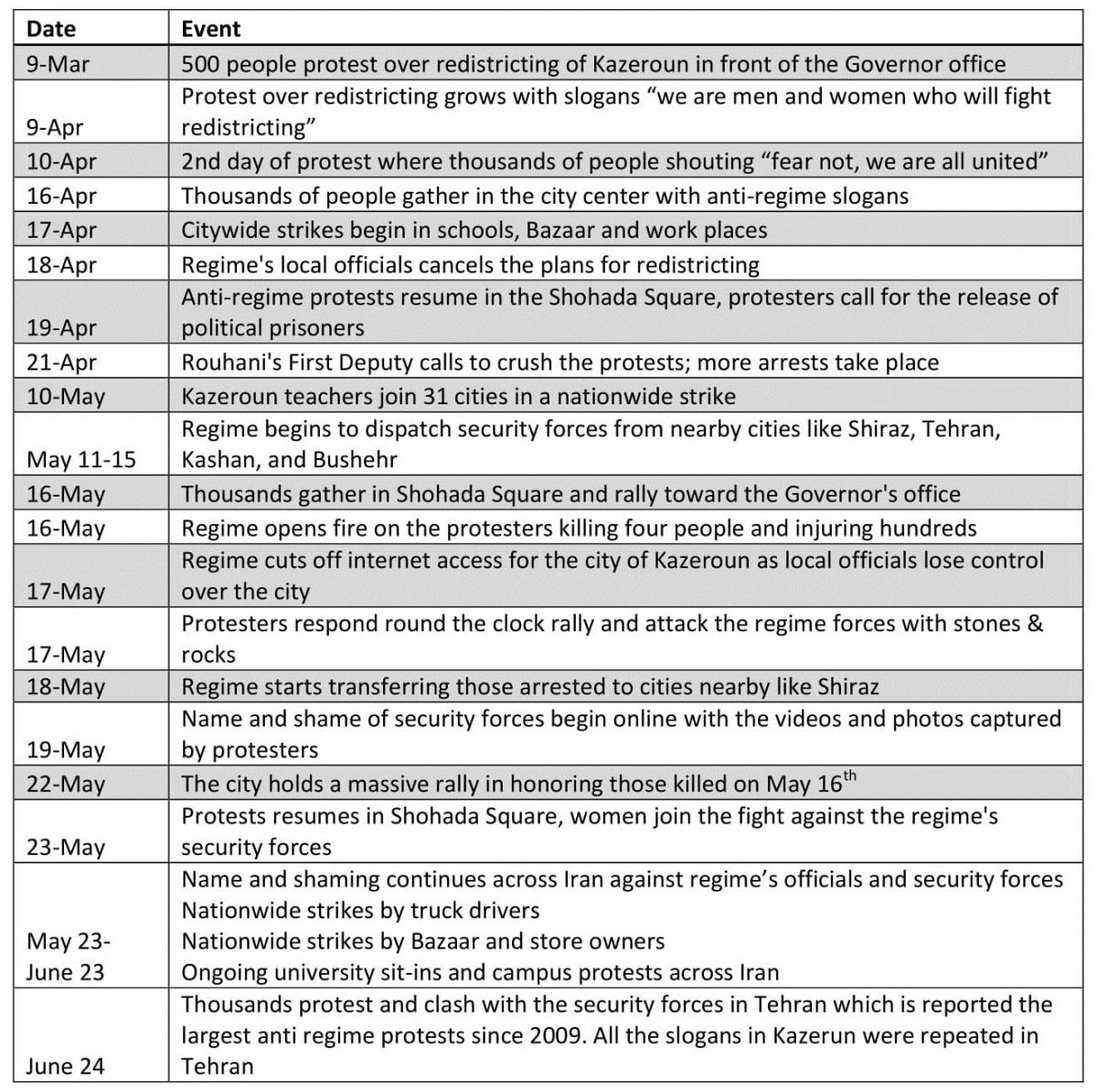

As radicalized protests have spread across various cities in Iran, especially in the city of Kazerun in the southern province of Fars [Table 2], mainstay Iranian news outlets like Keyhan, which boasts direct ties to the office of Iran’s Supreme Leader, have pointed to the MEK for their role in precipitating unrest. In a televised talk by Ali Akbar Raafipur, a pro-Khamenei university professor, admitted the Kazerun protests only needed “two members” of the MEK to become radicalized.

In a standoff between the people and regime which lasted for weeks, the protesters showed impressive discipline, collecting live news and dispatching it through various online outlets despite heavy-handed internet restrictions. More poignantly, protesters in Kazerun made explicit reference to the MEK’s passed legacy of armed resistance to Tehran shouting “beware of the day we take up arms” as the regime’s security forces opened fire on them, wounding and killing dozens. The unarmed protesters, especially the youth, undeterred by the regime’s bullets, were able to take control over the city of Kazerun for two days. Analyzing the video clips, photos and testimonies by those from Kazerun, the city was united and defiant in its resistance to the regime’s bloody attacks. Kazerun’s Bazaar, schools and work places all joined in solidarity with the street protests and went on strike. On April 21, 2018, the Kazerun protests with radical messages and slogans and the inability for the local security force to respond, reached new heights forcing Rouhani’s first Deputy, Eshaq Jahangiri, to say: “the Kazerun problem has to be dealt with, it is not acceptable that every day people pour into the streets in various cities…these problems should not lead to a crisis and become a pattern…we should not allow these problems to become political, social and security challenges for us.” On May 16th, thousands of protesters in Kazerun’s main square rallied towards the officer of the governor while chanting “our enemy is here, they keep blaming the US.”

The swift reaction by UN officials, US and European governments in support of the protesters in Kazerun also put the regime on notice that the world is watching very diligently.

Chronology of Events in the City of Kazerun and Elsewhere[1]

On June 24, Tehran protest began with people’s call for a strike, followed by Bazaar closure and street protests and rally towards the Parliament. Similar to Kazerun, protesters fought back with rocks and stones in response to security forces attacks. According to eyewitnesses, in a matter of two hours, the slogan of “death to high prices” became “death to dictators.” Again, the fingerprints of the MEK can be seen in Tehran’s protest. The Iranian security officials say “they have hard evidence that the protests were directed from abroad…many rioters arrested in the unrest have been trained by the MKO [MEK].”The city of Kazerun clearly set a new example for other cities to follow, more specifically, the capital city of Tehran.

Iranian View of MEK: A Partner for Change or a Threat?

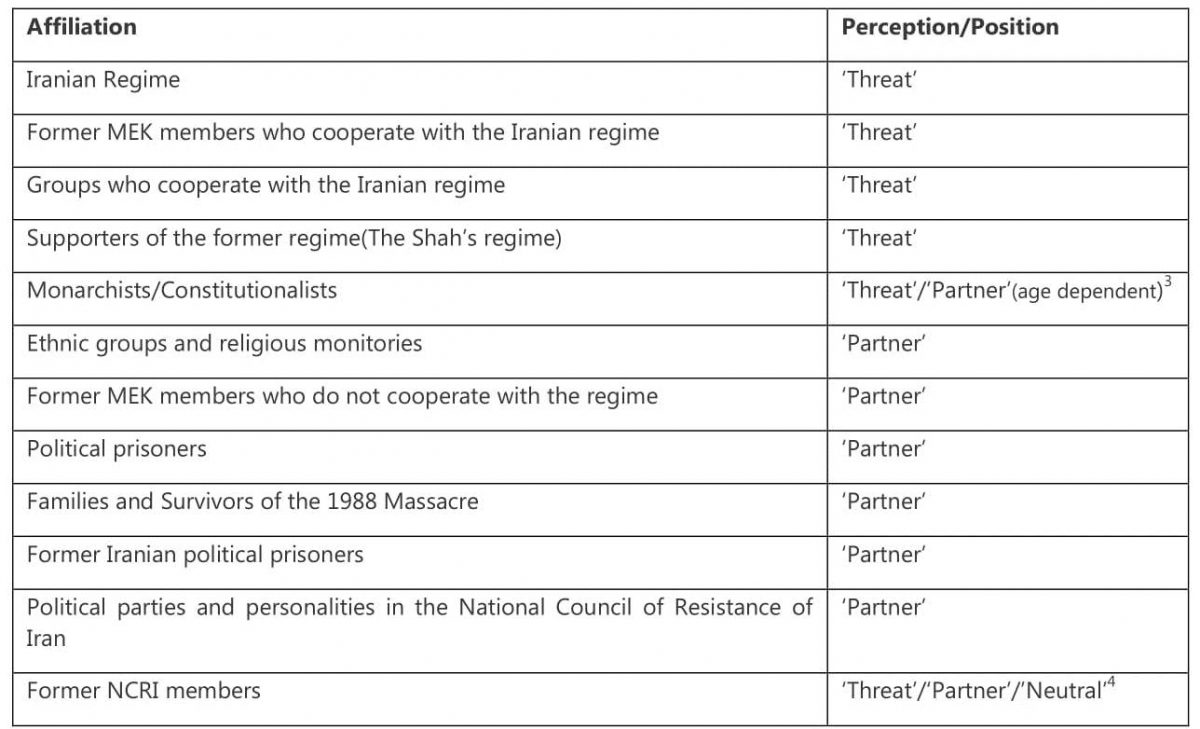

Not a day has gone by since last December’s nationwide uprising and the ensuing daily protests and strikes across Iran, in which the MEK is not talked about, negatively or positively, in either Iran’s state-run media or in some foreign media outlet. Notwithstanding state media which obviously see the group as the enemy, the MEK has been portrayed as either a partner or a threat, and hardly anything in between. What is interesting to note are the source of affiliations that correspond to the dichotomous views espoused vis a vis the group. [Table 1]

High-level Typology[2]

In the early 1990s, a new tactic to demonize and discredit the MEK was designed by the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS). According to Federal Research Division of US Library of Congress, “after the 1991 Persian Gulf War against Iraq, MOIS made anti-MEK psychological warfare one of its main objectives, but MEK nonetheless has remained a viable organization.” Employing a KGB-style approach, the Iranian regime focused on polluting and obfuscating the minds of Iranians, both at home and abroad, to establish itself as ‘the lesser of two evils’. MOIS and multitudes of its semi and non-governmental offshoots then took up to develop targeted narratives and talking points aimed at discrediting the regime’s rivals. Previous analysis of these narratives also reveals their level of sophistication. A mainstay of such talking points is that they typically feature harsh criticism of the Iranian regime to legitimize their subsequent criticisms of the MEK.[5] Elsewhere, mentions of the MEK, and the threat that they pose, figure into their debates as a complete non sequitur. The same analysis also shows, these narratives have been massively propagated through various MOIS channels and parroted by a handful of exiled opposition figures and groups, including publication in various reputable western media outlets.The dominant public narrative separates the MEK members from its leadership. The majority of Iranians view MEK members as the “best” Iran has to offer. Where the views diverge is as it regards the MEK’s leadership. More specifically, those who came to know the MEK, directly or indirectly, through the narratives of the current or former (monarchist) regime, routinely oppose the group and view them as a threat. On the other hand, those who have directly worked, engaged, and interacted with the group through relatives or intermediaries consider the MEK as a ‘partner’. This might explain why the opposition to, and generally negative view of, the group is often based in superficial claims and, very rarely, grounded in facts.

By 1997, MOIS’s campaign against the MEK picked up steam. The more hit pieces were repeated by various outlets, the more credible they seemed and harder to refute. It was a clever tactic to turn a lie into a fact by sheer repetition. The spread of the regime’s content, however, outpaced the MEK’s ability to respond. The regime’s anti-MEK campaign was also coupled with intense lobbying effort in the West to create a softer image for the Islamic Republic of Iran ushering the era of reform movement that began with Mohammad Khatami. In October 1997, the Clinton administration, in what the Los Angeles Times reported was ‘a goodwill gesture to Tehran’, blacklisted the MEK as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) as demanded by Tehran (Kempster, 1997).

One can argue that the regime’s entire strategy against the MEK fully came together in 1997. In my previous piece ‘Is Revolution Brewing in Iran’, I discussed the regime’s fixation with the MEK at length. In brief, Tehran’s concern with discrediting the group is foretold by their decades-long political rivalry. But the question remains, why does there exist such fervent debate about the MEK among groups in exile?

The most striking example is that of the son of the deposed Shah, Reza Pahlavi. For Iranians, Pahlavi’s lack of political competence and effective organization, his monarchic lineage and seasonal attempts at leadership (record shows he mainly makes the media rounds on customary Persian holidays and whenever there is an uprising in Iran) has long meant his irrelevance for politics. Not to mention the past association and collaboration of the Pahlavi monarchs with the ideological and political ancestors of the ruling theocracy, as in the case of the 1953 CIA-backed coup against the democratic government of Mohammad Mossadegh, which continues to be a sore point for the Iranian democrats and revolutionaries (Woodward 1986).

Nevertheless, in his recent interview, Pahlavi declared that he “promotes a democratic revolution [in Iran]” one modeled after Gene Sharp’s theory of nonviolent social change. Iran’s ruling theocracy has demonstrated the will and capacity to survive at any cost. Pahlavi’s idea that they will relinquish power in a non-violent revolution seems an outlandish proposal at best. In the same interview, Pahlavi says he is not eyeing the throne and has “no personal ambitions other than to help the liberation of the Iranian people from the mullahs.” However, turning the audience’s attention by way of a complete non sequitur, he further declares “If the choice is between this regime and the MEK” people will “mostly likely say the mullahs.”19While this refrain is a common trope among diasporic pundits, it is even more confusing in the case of an opposition figure who talks about building bridges and nurturing unity among Iranians. Why so disparage another opposition group that the regime considers as its main rival? Simply because Pahlavi is a pretender and not a serious contender when it comes to opposing the regime in Iran. This is another example of his utter lack of political acumen and leadership tenacity.

Historic Retaliation

The political discourse on the MEK is often mired in blind, unjustifiable, or very misplaced hatred, as well as based in superficially constructed narratives. For example, one question that continues to get air-time is “why did the MEK side with Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq war?” Such allegations are a prime indicator of bias, as they originated with, and were propagated by, the Iranian regime. The baselessness of such claims is further bolstered by the fact that no credible evidence has surfaced, 15 years after the fall of Saddam, to support these allegations. The MEK, whose only connection to the Iraq was their refuge on Iraqi soil, no longer have any physical presence there. Without any objective investigation and study of the MEK’s historical publications and statements which explain the domestic, external, and the geopolitical situation under which the organization had to relocate their headquarters to Iraq in the 1986, such statements serve as nothing more than retaliation, one that relies on a biased account of history.[6]

Such forms of historic retaliation are not unique to the MEK. The African National Congress (ANC) was met with the same during their fight against the apartheid regime in South Africa. According to Stephen Ellis’s history of the ANC in exile, “The ever-evolving relationship in exile between the ANC and the South African Communist Party was a constant source of friction and intrigue.” In the case of South Africa, after the fall of the apartheid regime, the nation had the courage to hold the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to shed some light on the facts surrounding the ANC.

For the MEK, or any other political opposition group for that matter, this day has yet to come. In the meantime, the MEK and its allies are faced with the daunting task of wading through the multipronged smear campaign being waged against them. Not only does the sheer volume of mostly replicated, unsubstantiated allegations detract from their time and resources as a matter of strategic warfare, they are rarely invited to speak to the allegations made against them. While most of the demonizing tropes in circulation can be directly traced back to the MOIS or to ‘investigative reports’ featuring a steady cast of MOIS-linked former members, very little room has been made in popular medias for the organization to have a turn in speaking its part.

In 2011, an independent assessment by Ambassador Lincoln Bloomfield, who previously served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, debunked a set of these allegations against the MEK and diligently traced them back to the Iranian regime as the originating source.

The most important ramification of such biased reporting is that, in the absence of other large-scale oppositional movements, it uniquely benefits the Iranian regime. This is all the more true and critical as it relates to youth’s perceptions in Iran who, on the one hand, are the principal agents of the on-going revolution and,on the other hand, hold no memories of the MEK’s presence as a public organization because the group has been organizing underground since 1981. With the mass executions, the Iranian regime made it abundantly clear that any public affiliation or association with the MEK is punishable by death.

During the 2009 uprisings in Tehran, the nature of such discursive warfare was most telling when Iran’s government officials went so far as to claim that it was the MEK who killed Neda Agah Sultan, the peaceful protester slain by a rooftop sniper and whose tragic death was caught on video.

The Iranian regime’s targeted demonization campaign against the MEK reached new heights with the 2016 release of “Midday Adventure”, a film aimed to depict the nature of the group that stands for ‘senseless violence’ and is ‘responsible for killing innocent Iranians’. Such constant flows of dreadful narratives coupled with venomous online content is enough to shy the average viewer away from the MEK, never mind supporting the idea of a revolution promoted by them.

A Shift in Favor of the Truth

There came a watershed moment in 2016, however, when the Iranian regime’s ‘cliché’ on the MEK was the shattered by the discovery and disclosure of the late Ayatollah Montazeri’s private audio recordings. Leaked to the public by the Ayatollah’s son, the tapes captured private conversations where Ayatollah Montazeri criticized and questioned the officials engaged in the 1988 massacre. The Ayatollah warned the regime that “you cannot eradicate their beliefs by killing them all.” The taped discussion reveals details on the roles, responsibilities and the repercussions for the mass killings of MEK members. For the first time in decades, irrefutable evidence exposed the regime’s purposeful targeting of the MEK because of their beliefs. For the first time, those born in the years after 1989, learned about the MEK’s popularity in the 1980’s, when their public speeches, gatherings, and protest rallies drew hundreds of thousands of supporters. The younger generation is only now beginning to understand why the regime views the MEK as its existential threat and uses all its state resources to destroy them physically, organizationally, and politically.

Coinciding with recent upheavals, this generation’s new-found familiarity and appreciation of the organization’s revolutionary history has spurred numerous intrigues and conversations about their role in Iran’s future political landscape. Countless cyber outlets and social media platforms now feature conversations around understanding “who are the MEK and what do they stand for?”

For its part, the MEK is actively finding new ways to connect with younger segments of Iran’s population so they may get to know the organization and their platform in their own right. On January 26, 2018, Ahmad Jannati, the head of Iran’s Assembly of Experts admitted: “cyberspace is a blow to our life” (Iran: cyber repression, 2018) The MEK’s cyber outlets are actively updated with documentaries of their efforts in the last four decades. Various live Q&A forums are hosted online and via satellite broadcast where people can call in or live-chat their questions about the group.

Annually, tens of thousands of the MEK’s supporters from across the globe participate in the annual international convention hosted by the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI), the political coalition in which MEK is a member, in Paris, France which offers an in-person opportunity for those in exile, or whom have recently fled Iran, and who seek to familiarize themselves with the group. In recent years, an increasing number of Iranians who left Iran in the aftermath of a crackdown following the 2009 uprising and whose views of the MEK was negatively influenced by the regime’s propaganda have been joining the group’s support network abroad, publicizing their solidarity at rallies and posting their support on social media.[7]

Increasingly, other exiled groups and personalities not influenced by the MOIS’s propaganda have recognized the MEK’s contributions and their direct role in the recent uprising and ongoing protests. In one online article, an Iranian political essayist writes “let’s not forget that today we may be busy with undermining each other and that is a huge mistake…a mistake that is registered daily on Twitter, Telegram and Instagram…What we say today on social media will be tomorrow’s subject of research by historians and it will reflect the level of our generations’ political awareness…if we get lost in the abyss of confusion that the regime has created over the last 40 years about the MEK, we will deprive ourselves from working with a partner in overthrowing this regime” (SaadatGharib, 2018).

In closing

Comprising the main component of the annual NCRI grand gathering in Paris that has drawn more than 100,000 people every year since 2004, the MEK has brought together political figures and officials from both sides of the aisle from US, Europe, and the Middle East. The MEK possess a leadership and management ability to operate a vast network of supporters in Iran that is unmatched by existing oppositional factions. At the very least, the MEK exemplify a rare oppositional force in Iranian history, one that is worthy of curiosity by those serious to understand the Iranian affairs.

Recently collected interview data from exiled Iranians reveals an interesting political development. Specifically, when asked about what’s next, respondents holding various political backgrounds have been recorded as saying “let’s hope the MEK bring this regime down because they are the only one who can.” [8]

In terms of events in Iran, what comes next will potentially be very similar to what took place in the city of Kazerun and Tehran. One can only hope those in exile will focus their energies squarely on the Iranian regime and fend of its efforts to weaken the oppositions’ unity. The time for Iran’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission can only come after democracy has taken root.

References

Varasteh, M. (2015). Understanding Iran’s national security doctrine. Leicestershire: Matador.

Kempster, N. (1997). U.S. Designates 30 Groups as Terrorists. Los Angeles Times. [online] Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/1997/oct/09/news/mn-40874 [Accessed 13 Jul. 2018]

Woodward, B. (1986). CIA Curried Favor With Khomeini, Exiles. The Washington Poist. [online] Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/11/19/cia-curried-favor-with-khomeini-exiles/9cc0073c-0522-44e8-9eb8-a0bd6bd708d1/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.c279e35c6158 [Accessed 13 Jul. 2018].

Iran: Cyber Repression. (2018). 1st ed. Washington DC: Iran: Cyber Repression. (2018). 1st ed. Washington DC: National Council of Resistance of Iran – U.S. Representative Office., p.18.

SaadatGharib, R. (2018). «سخنی هم با مخالفان و هم با موافقان مجاهدین» به قلم رامین سعادتقریب – ایران آزادی. [online] ایران آزادی. Available at: http://fa.iranfreedom.org/%D9%85%D8%AE%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D8%A7%D9%86-%D9%88-%D9%87%D9%85-%D8%A8%D8%A7-%D9%85%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%81%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%86-%D9%85%D8%AC%D8%A7%D9%87%D8%AF%DB%8C%D9%86/ [Accessed 13 Jul. 2018].

Notes

[1]Based on data collected from March 9–June 1 2018.

[2]Exhaustive study on this topic will be expanded upon in a forthcoming publication.

[3] Younger generation in this category tend to express similar views as the MEK when it comes to human rights, women’s rights, and rule of law. They often have little knowledge about the Shah’s dictatorial history and human rights violations against its political opponents.

[4] Some of the NCRI members cooperated with the regime hence the ‘threat’ designation, some have also left the NCRI for personal reasons, and are inactive in the political affairs hence the ‘neutral’ designation.

[5]Summary of the findings that have emerged from the forthcoming studies.

[6] The relocation took place four years after Iraqi army had completely pulled out of Iran territory in 1982, there was an internationally-backed cease-fire proposal on the table, and it was Iran which was on the offensive, fulfilling Ruhalla Khomeini’s vow to conquer Jerusalem via Karbala with catastrophic military results and huge loss in blood and treasure of Iranians.[ ] The “siding with Iraq” assertion also negates the simple historical fact that when Iraq invaded Iran in 1980, the MEKstrongly condemned the attack and the ordered its members and activists to participate at the frontlines where many of them were killed, wounded, or captured by Iraqi army. After the war ended in 1988, Red Cross arranged for transfer of several hundred Iranian POWs who were MEK supporters and wanted to re-join the MEK ranks rather than going back to Iran.

[7] 2017 interview data with several student activists (men and women) who fled Iran after 2009 and now living in Germany.

[8] The narrative data is compiled based ongoing study of the Iranian opposition in exile. The question was posed to participants during 300 interviews (phone and online) with Iranians in US, Canada and various countries Europe and Australia.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – The Iranian Regime’s Continuing Oppression Amid Growing Protests

- Opinion – Iranian Soft Power in a Post Soleimani Era

- Engaging Iran

- Opinion – Iran 2020: Election Polls, Panics and Predictions

- Opinion – The Iranian Regime’s Future Post Soleimani

- Opinion – Environmental Loss and Repression in Iran